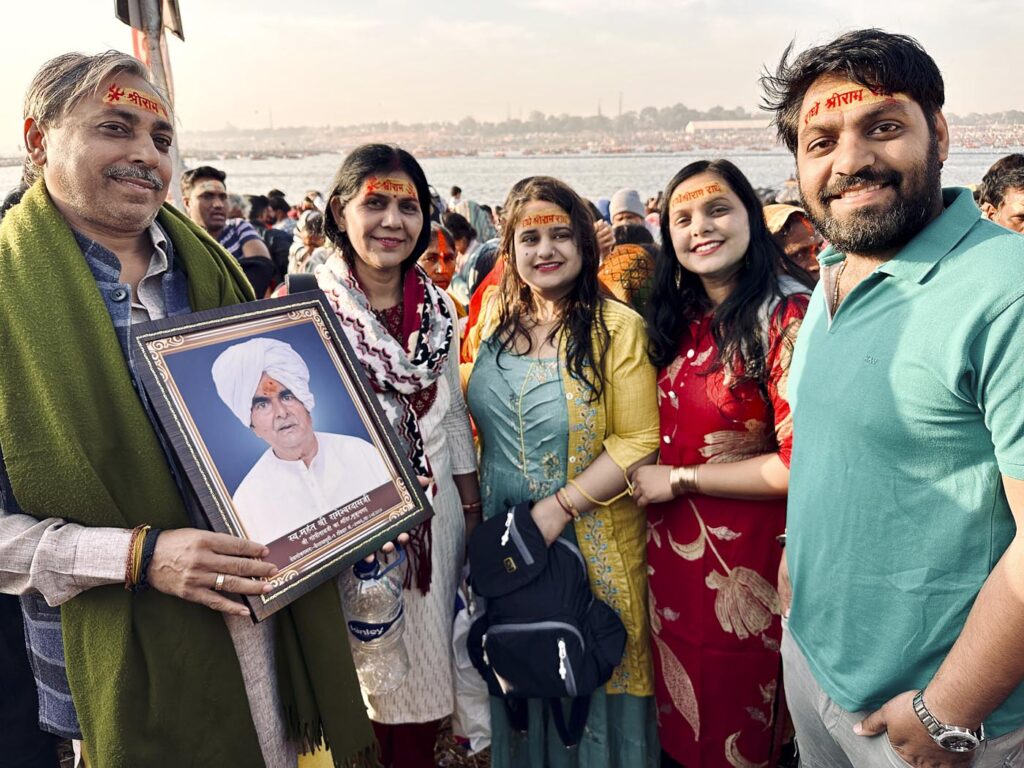

The sacred bath in Ganga’s lap, they say, connects them and their families to ancestors and descendants in a timeless moment of grace

By Ellen Coon, from Prayagraj

At least half of the pilgrims i saw at this year’s Maha Kumbh Mela were women. Preliminary estimates say 660 million people attended the festival. That means nearly as many women as the entire population of the United States, 340 million, were there. Not just pilgrims—women were visible in a variety of roles, from religious leaders and saints, to vendors, policewomen and temple attendants. I was curious—what is this historic event like for them?

Most pilgrims take advantage of the Kumbh’s proximity to Kashi, visiting the holy city immediately after or before their trip to the Kumbh. Some of the interviews presented here were done in Kashi, with women who had just come from the event.

Experiencing the Kumbh Mela

Both getting to the Mela and being there are hard on the body. Like everyone else, photographer Thomas Kelly, translator Pratiksha Patel and I walk for miles through moving crowds so dense we sometimes feel squeezed on all sides. Even so, almost all of the women I encounter are shining with happiness—they have won the astrological lottery. Under a rare cosmic alignment, an enormous gush of heavenly power is pouring down into the Ganga River confluence, so auspicious that bathing in it can change your life, and your family’s life, for the better in an instant. Of course that is true for men as well as women. But the women I meet seem to feel blessed not only as human beings, but as women. They have received a kind of positive affirmation of their own worth that has helped them, both with their outer family roles and with their inner spiritual lives. Their stories help me understand how their experiences both liberate them personally and keep them connected to a larger divine reality.

The River and the Saints

A woman at the Kumbh immerses herself in this divine reality when she enters the river, stands praying for a few moments, and then takes her “holy dips,” bending her legs with her back straight until the water closes over her head. The most powerful spot to bathe is the Triveni Sangam, where Ma Ganga is joined by the Yamuna River and the invisible Saraswati River. A pilgrim looking at the river perceives its multiple identities—as purifying water, as a divine female body, and as one or more Deities, each with Her own characteristics and story.

Each element of the Kumbh is like that—a physical reality that points to an expanded divine identity. For example, women pilgrims tell me when they see saints at the Kumbh, they see them as human beings and as manifestations of Lord Siva.

At the Kumbh, the presence of so many saints renews the story of how Lord Siva made it possible for Ganga to pour down from Heaven. The story erupts from eternal time into the present. Ganga was a celestial Goddess made of the Milky Way. To allow the divine river to descend without hurting the Earth, Lord Siva caught Her in His sadhu topknot, so the waters could trickle safely down His dreadlocks. One woman explains that the thousands of saints camped on Ganga’s banks make each other more powerful: the saints’ tapasya, or austerities, generates a tremendous energy that infuses the river when they bathe, while Ma Ganga Herself purifies the saints and electrifies them with cosmic energy. Just seeing the matted hair of the saints at the Kumbh is a blessing.

Taking a Holy Dip

We arise on February 16th while it is still dark and hasten to reach the Sangam by dawn. People hope to enter the water at sunrise, though they bathe in the Ganga and at the Sangam at all hours of the day and into the night. I can hear singing and chanting as beautiful golden light suffuses the scene.

A view from far above would show the riverbank and the shallows alive with a glittering mat of humanity extending for miles. Everyone is pushing their way to the riverbank, climbing into the water, spending a few minutes in it, scrambling back out, and changing wet clothes as modestly as possible, while others assemble fragile offerings of leaves and flowers on the bank, and police officers push their way back and forth telling people not to linger, to move along. I don’t see anyone getting angry. People treat each other kindly, or at least tolerantly, as elation breaks out on faces and some laugh aloud with joy.

I ask people climbing out of the water how they feel. “Energized! The energy! It’s amazing!” says a man of around 40. “I drove 15 hours from Delhi, all night. Do I even look tired?” He is a manager in a factory that makes rods and pistons who has come with his colleagues. Other men describe how the water has removed a lifetime of fatigue and hit a powerful reset button in them, charging them up. “It’s Ma’s shakti!”

Women tell me the water’s marvelous vitality can instantly restore health—and not just for oneself. By bathing at the Kumbh, a woman can lengthen the life of her husband, even if he isn’t here. Husbands and wives taking their holy dips in pairs, holding each other’s hands, strengthen their eternal union. I am told that afterwards, a husband applies fresh red vermilion powder with a fingertip to the parting of his wife’s hair, just as when marrying her, and presents her with new wrist bangles.

Caring for the family’s well-being is a primary responsibility for most Indian women, and a focus of their religious life. Mrs. Indu Sharma, who has come with her husband and relatives from Haryana, tells me her holy dip has helped the whole family. “I only look like one person. But when I entered the water, I brought everyone with me. I could feel them with me. I took one dip remembering my deceased mother and father, another dip for my husband and his family, a dip for my brothers and my sisters and their families, a dip for my children and their families. All of them—even those who are deceased and those yet to be born—are purified of their wrong karma and become lighter. As a family, we become stronger and more harmonious.”

Climbing into Your Mother’s Lap

Women in particular describe Ma Ganga in personal, intimate terms, as their mother’s body. They make offerings to the river of saris and bangles. In the early morning, they bring Her cups of tea and pour them into the water. They leave invitations to their children’s weddings on her banks.

I meet Raghni Mishra in the bright early morning light of Magh Purnima, the full moon on February 12, in Kashi. She has taken her holy dip and is making offerings to worship the river Goddesses. I ask what it felt like when the water closed over her head. “I feel like I have just climbed into my mother’s lap,” she says. “Her lap is always there, always ready to take me, and when I’m inside the water I feel the utmost peace. Bliss. I don’t want to come out.” Her daughter, Adishri Mishra, age 13, added, “Unlike our human mother, Ma Ganga is very calm. She never gets angry, and she forgives us everything.”

A large group of Rajasthani women is emerging from the water, laughing and teasing each other, their wet clothes plastered to their bodies. “Yes, as a grandmother I’m very old to need a mother,” jokes Panno Devi. “But even so, we do! Our Ma Ganga… the feeling between us can only be called pyar, love. She loves me, and I equally love and adore Her. She gives me pardon for all my mistakes and says, ‘Never mind! It’s all right now.’ ”

Beyond the riverbank, I encounter Vaishnavi Guwlli, 17, who has already taken her holy dip and is wearing a purple, Western-style dress. She has come from Hyderabad with her father and relatives. She says, “When we get into Ma Ganga… it’s like when we creep into our mother’s lap and she covers us up with the pallu of her sari to cuddle us. When the water covers us, it’s like that. You relax completely; it’s like a mother carrying her child. And when Mother is carrying you, no worries, we don’t have to take care of anything.”

She is startled when I mention that a Western person might hesitate to get into the river, thinking it dirty. “No, no! No matter what is on her clothes, Mother can never be dirty! However she looks, we don’t care—She is my Mother. That’s it. She is everyone’s mother.”

We Should Be Like Her

After taking their holy dip, people stand around chatting with paper cups of tea bought from vendors who make it in big aluminum kettles over hot charcoal. Dr. Deepika Sethiya, an ayurvedic doctor who practices in Pune, has come directly to Kashi from her dawn dip at the Kumbh and is relaxing with elder female relatives. I ask how she is feeling—”Very light, joyful! The water comes straight from Lord Sivaji and Parvati, and so obviously it feels amazing!” She continues, “We [women] should be more like Ma Ganga…. You should be pure. You should have your femininity. You should be delicate and soft.”

For some reason this made me, as a Westerner, anxious. “That doesn’t mean you aren’t strong?” I interjected. “And what do you mean, by feminine?”

Sethiya answered, “Parvati is there, for strength. Strength can be delicate. Feminine means, you know your worth. Obviously, we should dress up well, but that’s for yourself; there is no need to put on a show for anyone else. Ma Ganga is motherly. She is warm, she is loving. We should be like Her.”

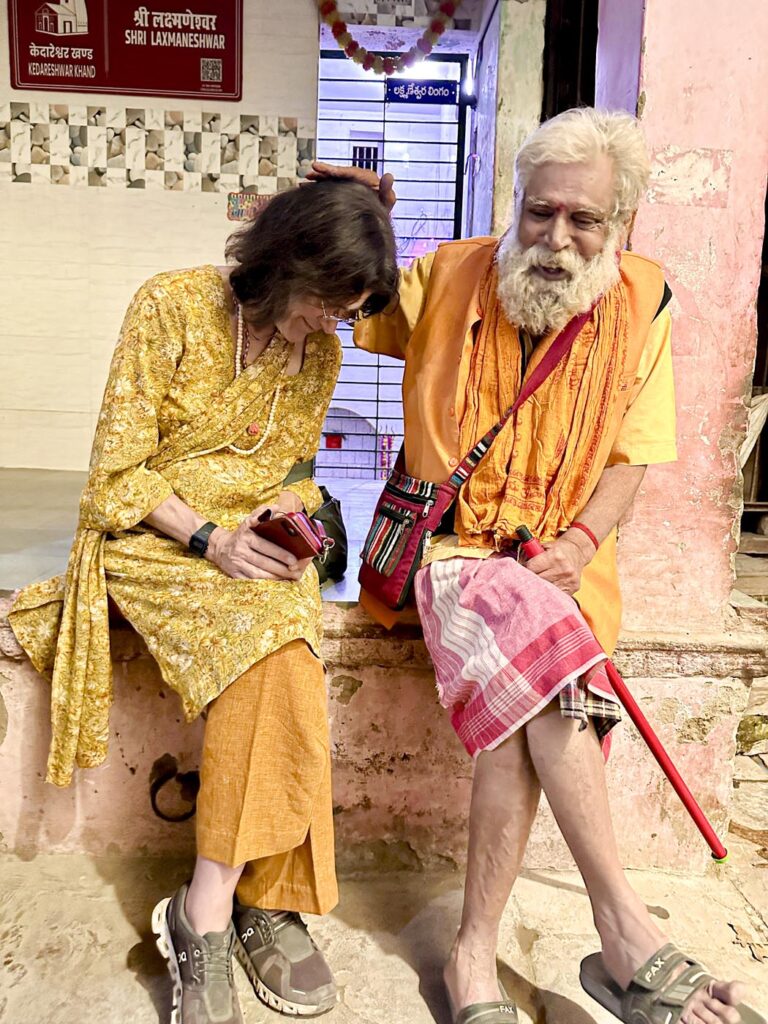

Seeking the Blessings of the Saints

There’s a storied relationship between the figure of the pious Indian householder woman and the wandering sadhu or renunciate who appears at her gate to be fed and honored. In legends, these encounters are usually one on one. At the Kumbha Mela, millions of householder women come together with thousands of sadhus, all at once. There’s also an inversion in their relationship: the sadhus are settled into semi-permanent encampments according to monastic orders, while the householders are the ones on the move, walking from the riverbank after taking their holy bath, seeking the blessings of different sadhus as they move from camp to camp, and visiting important temples, often within a single day or a couple of days.

Here, it’s the sadhus who feed the householders. Most sadhu orders, akharas, offer free meals to pilgrims, as well as a central area where pilgrims can lie down under a blanket for the night—though plenty of pilgrims just bed down in the open on the soft, sandy ground. Offerings of money are accepted, but not compulsory. Saints sometimes give money to pilgrims, too.

As the sun climbs the sky and the morning grows hotter, we follow streams of pilgrims walking up into the main areas of the encampment, looking for saints after their holy dip. Two Naga sadhus smeared with ash stand on a platform by the road. Each holds a bundle of peacock feathers and blesses the people shuffling past with a feathery tap on the head. It is a long line, with more women than men. The pilgrims and saints kept chanting “Har Har Mahadev!”

I ask a young woman dressed in green, her head covered by the end of her sari, if she feels embarrassed by the Nagas’ nakedness. She says it is the opposite: their nakedness is a sign of their great discipline. “Look, it’s very cold; an ordinary person can’t go without clothes. When I see the Naga, I bow to Lord Siva in front of me and say, Jai Bholenath! Plus, we don’t see a Naga saint very often, some people never see one. They usually do meditation and tapasya alone in a wild place, like a cave or in the jungle. When they come together here, it creates a huge energy. The blessing of the Naga is the most powerful.”

Throughout the day, I see women pilgrims sitting with Naga sadhus and saffron-clothed saints near their sacred fires, by the twos and threes, bowing, receiving blessings and also whispering the questions or troubles closest to their hearts. One woman shows a Naga a sapphire she purchased on the advice of an astrologer. The Naga baba examines the gem carefully and indicates that it is a fake. Upset, the woman sits near the saint for some time. He blesses her by touching her shoulder with his iron fire tongs, then uses them to scoop a bit of sacred ash from his dhuni (sacred fire) and hold it out to her. She dips her finger in the ash and smears some on her forehead, then sprinkles the rest on her head and into her mouth. The saint gives her private instructions, then folds a 100-rupee note around some ash and gives it to the woman, whose face relaxes with faith and gratitude. Each woman who bows down before the saint receives his blessing and careful attention to her problem.

Two older women who have come by bus from Delhi sit next to me and other devotees on a piece of carpeting across the dhuni from the Naga saint. They tell me they have been at the Kumbh for two weeks and have taken a holy dip every day, then sought the blessing of every saint and sadhu they could find. Leaning forward, Ramamurti showed me her knees and said, “I have been healed of my pain. It was a terrible problem for me, I couldn’t even walk, and now it’s gone. The saints have healed me—this one most of all. He is a real one, he embodies sat, Truth.”

Disciplined Saints Are Real Saints

Pilgrims at the Kumbh don’t just seek blessings from saints and sadhus. Coming together from all over India gives potential gurus and disciples the chance to find one another and make lasting bonds. Many women pilgrims tell me they have a guru as their spiritual preceptor back home; others tell me they have not yet met their guru. But with even the government publishing lists of “fake gurus,” how can they know whom to trust?

We are sitting near the dhuni of a Naga saint who was three years into a twelve-year vow of silence. His eyes flashing, he gestured for a junior Naga to come before him. We met this person earlier at the gate of Juna Akhara, wearing dozens of jingling necklaces and flashy rings, offering us black magic, palmistry, and other dubious services. Now, without speaking the respected saint gives him a furious interrogation. Dissatisfied with the answers, he begins to beat the offender on the back and shoulders, first with his iron fire tongs and then with a club. He strips off the offender’s necklaces and has him thrown into the street. An hour later, with the intercession of a respected sadhu, the chastened man creeps back in and prostrates to the senior saint. Holding his earlobes in a sign of contrition, he vows he will never act the charlatan again, begs for forgiveness, and promises to spend his days and nights in intense practice. The women watch quietly and nod. Seeing the Nagas’ discipline increases their faith.

Women Saints and Women Gurus

Several hundred women Naga sadhus, or sadhvis, are initiated at the Kumbh this year after the male Naga sadhus, in a highly photographed event. Spaces for female saints within the akharas are now larger and more visible than earlier.

Like most other sadhus and sadhvis at the Kumbh, Naga sadhus belong to one of thirteen akharas, highly structured and hierarchical monastic orders. Their organizational structure can be seen in physical form as we walk past each akhara’s tented encampment. Some have fantastic gateways—there is one in the shape of a large rocket ship—and pennant flags on tall bamboo poles, fluttering in the breeze. Adi Shankaracharya, an 8th-century Vedic philosopher-monk, is credited with founding the akhara system as well as the Kumbh Mela gathering at Prayagraj, in part to defend Hinduism against invaders.

On Magh Purnima in Kashi, we meet Mataji Meenakshi Giri, a member of Juna Akhara, who tells us about her initiation as a Naga Sadhvi. Just over 50 years old, she completed 12 years of preparatory practices as a brahmacharini before coming to the Kumbh. Although she is South Indian, from Chennai, for the last three years she has practiced intensely alone in the forests of Uttarakhand, at 10,500 feet in altitude. We are sitting together outside Juna Akhara when she begins by telling me, “Naga means warrior.” Her spiritual path demands courage.

She said, “My struggle has been such—always struggling. Climate, food, environment—everything was totally different. Practice, practice, practice, I kept going.” She shows me a leopard’s claw around her neck. “I was in deep forest. Can you imagine, leopards just walking past me openly. Guru gave me this to not be afraid. So I’m carrying myself like a leopard, so the smell, they understood. I walk at seven or eight o’clock now and nothing happens. Then, leeches, O my God, all over my body. I had never seen them before. It’s one thing to practice tapas in a nice building, but in the jungle, fear automatically comes. You have to face it.”

At the Kumbh, dressed in white and with their heads freshly shaven, she and other initiates perform the pinda daan rituals. These are final offerings for all of her ancestors, as well as her own death rituals, ending her previous family identity and preparing to be reborn as a Naga sadhvi. She said, “My grandma, my grandfather, everybody—I felt their presence in the astral plane very close and near. When I closed my eyes, all of my ancestors came to give me their blessing.… It’s very simple, but intense, the vijay havan sanskar. In 24 hours at this Kumbha Mela I was newly born. New born, I made offerings for the dead to myself, too. So now I am a new baby, born this 28th of January.

“I feel a lot of liberation. I’m not talking about physical liberation, no, it’s a feeling of liberation with everything. I feel very light, peaceful. Everybody is like my close relative; I feel warmth toward everyone.”

She describes the feeling of bathing at the Sangam and of meditating on the riverbanks. “Ganga is raw energy. We take a holy bath and call it Ganga water, but that is actually raw energy. The sand, too, is always purifying the raw energy. And that is increased by so many Nagas coming together. We Nagas have been in the forest, been in the mountains, doing intense practices (tapas) and worshiping Agni by tending our dhuni, sacred fire. When even two Nagas come together and meditate, it increases the energy so much, you can feel it. Imagine what happens when all the Nagas sit together at the Kumbh. The body—automatically vibrations will come.

“During the Kumbh, especially the Maha Kumbh, all the devatas and Deities come to the Sangam in astral form to absorb the blessings and distribute blessings to everybody there. You can feel their presence even if you can’t see them. Not just Deities—gurus and rishis who have left their physical bodies in the last 200 or 300 years still come in their astral or subtle body (sukshma sarir) to give us blessings and teachings.”

She tells us she has experienced this herself, while meditating at the Sangam. Remembering that Mahavatar Babaji—a 2,000-year-old hermit saint who is said to still have a physical body—showed himself to Swami Sri Yukteswar at the Prayagraj Kumbh in 1894, she prayed to Mahavatar Babaji: “You come and meet me, I want your presence.” Suddenly, her eyes closed, she sensed a huge foot coming out of the river and then another, the feet planting themselves on either side of her. Mahavatar Babaji was indeed at the Kumbh and had blessed her new life as a Naga sadhvi.

Women Nagas wear saffron robes, and when bathing wear a single piece of unstitched cotton cloth. Meenakshi Mataji says that when they perform those Digambara sadhanas that require them to be naked and smear themselves with ashes from their sacred dhuni, for practical reasons these are done in private. But she cautions women not to over-identify with our gender. “OK, when you get married, when you give birth, at that time we are identifying with our female body. But otherwise, don’t go around 24/7 thinking, oh, I’m female, I am female. The soul is One.”

Despite Meenakshi Mataji’s downplaying the importance of gender in spiritual life, at the Kumbh I can see gender categories being actively negotiated, with expanded recognition and opportunities for women. In 2019, Juna Akhara began the formal initiation of Naga sadhvis at the Kumbh Mela; and in 2018, Kinnar Akhara was formed as part of the Juna Akhara, for non-gender-conforming sadhus. There have always been female gurus with both male and female disciples. Some women gurus are explicitly working to increase respect and support for women as women.

Although we do not meet her, we walk into the encampment of Anandmai Puri, the Mahamandeleswar of Niranjani Akhara, who has the authority to teach and make initiations. Inside, two policewomen are relaxing in the warmth of the afternoon, their boots unlaced; one of them has her thirteen-year-old son leaning against her arm. They convey a sense of ease and well-being that is difficult to describe. A feeling of rightful place.

A Symbol of Unity for All Indians

Walking near the river later that afternoon, we meet Laxmi Devi, who is sweeping the road with a long-handled broom made of stiff twigs. She is wearing the government-issued vest of an official sweeper. She says she feels proud of her service. “This Kumbh is for everybody. Anybody and everybody can come here and take part in the blessings.” She continues, “Ma Ganga is my Mother, She has bestowed me with my life and my livelihood. I see myself in Her—She is so hardworking, always taking away everyone’s dirt and sin without ever complaining. When I enter the water, I feel Her sweep my burdens away, and all my tiredness dissolves into a feeling of lightness, of bliss.”

She said, “Ma Ganga does not discriminate. She embraces everybody, male or female, old or young, rich or poor, saint or sinner.” Earlier the same day, Tejarao Guwlli said, “We have all come together because of our River Mother. Ma Ganga and this Kumbh are a symbol of unity for all Indians.”

Back to the Beginning

At the end of the day, we walk with groups of women who, accompanied by a male relative or two, are completing their pilgrimages with a visit to nearby temples. The first is a shrine to Adi Shankaracharya in the Shankar Vidam Mandapam, a Siva temple. The second is the Lete Hanuman temple, where a recumbent Hanumanji lies on the floodplain, covered with flowers. And the last is a large temple to Vasuki Nag Raja, the holy serpent king Lord Sivaji carries around his neck. These three temples near the Triveni Sangam function like pins dropped through time, bringing pilgrims into the eternal present of mythic events.

The women we meet know the divine beings and their stories intimately. They visit them in the temples with eagerness, not as a duty to be completed. Mrs. Menaka Mishra, from Bihar, offers marigolds to a black stone image of Adi Shankaracharya and tells me that he is the Adi Guru of the Kumbh.

Mrs. Kusum Lata, a policewoman at Guru Ma Anandamai’s camp, tells me having the darshan of Hanumanji is the high point of the whole Kumbh for her, since He exemplifies and strengthens her highest aspirations as a police officer: loyalty, strength and service.

Mrs. Indu Sharma, from Haryana, tells me Vasuki Nag is worn by Lord Siva and was the fulcrum between the Danavas and the Devatas at the churning of the ocean. She says it is very important to end one’s pilgrimage by bowing to Vasuki Nag, as well as to the Siva Linga and Hanuman at the temple.

It is nearly dusk, but the Vasuki Nag temple is still busy. We sit next to Priyanka Mali (photo page 32), who is selling flowers for offerings with her little daughter by her side. She tells us that unlike the temporary flower vendors at the Kumbh, she is of the Mali caste and this is her full-time work; she has sold flowers here every day for 14 years, since her marriage. “I love this place,” she exclaimed. “Even when I am anxious at home, I feel safe and relaxed here. How could I not? I am with my beloved Lord Siva, and His powerful Vasuki Nag, and Lord Hanuman, and my Mother Ganga.”

Although she had been too busy to take more than one holy dip since her marriage, Priyanka Mali was utterly determined to take one during this Maha Kumbh: “What am I doing living here if I don’t share the blessing of this moment, which will never in my lifetime come again?” On Magh Purnima, she rose before 3:00am to bathe at the Sangam, and reached her workplace by sunrise. “I thought the water would be cold, but when I got into Ma Ganga I found Her warm and very soft. The water’s touch felt soft. All of my worries and tiredness just melted away,” she says. “I feel I have done the most important thing I will ever do in my life.”

Connecting with Ancestors and Descendants

An Abundance of Women Saints and Sadhvis

Seeking the Saints’ Blessings

Flower Selling at the Mela

The Bath

Blessing for New Sadvhis

Temples Visited after the Sacred Bath

The Author Shares Her Experience

I bathed in ma ganga at varanasi on Magh Purnima, and at the confluence of the Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati rivers at the Maha Kumbh before we departed. Although I wanted to share the pilgrims’ experience, I was nervous that the water would be polluted. Instead, I was shocked by the beautiful sensations I experienced.

Ma Ganga felt soft and warm and bright, like astral champagne made of mother’s milk and starlight. Like many of the women with whom I’d spoken, I felt energized, elated, and deeply relaxed at the same time. My joy lasted the whole day. Bathing at the Sangam, I had a vision of all of my ancestors—and all of humanity’s ancestors—behind me, while my children and all future generations flowed in front of me. I felt their living presence very close, and a sense of love and unity I will never forget.

I am requesting a simple button to be able to share these articles from the Hinduism Today app. Unless I am missing something obvious, such a button does not exist. Would encourage the app has the same basic article sharing functionality of the various newspaper apps out there. These stories are too good not to share to people who would be helped by them

Namaste. Thanks for pointing this out, we hadn’t realized it wasn’t active. It is now active. 🙏🏼

Dear beloved Ellen,

I am blessed and humbled to read your eternal experience of Mahakumbha and great to see you after three years on zoom Newari language class. Many thanks for sharing your “atmatattva” and eternal feeling and happiness. You are truly a divine soul of sanatana or Vedic dharma and tradition.