The fascinating biography and “I-didn’t-know-that” facts of the unpretentious grain that feeds half the world

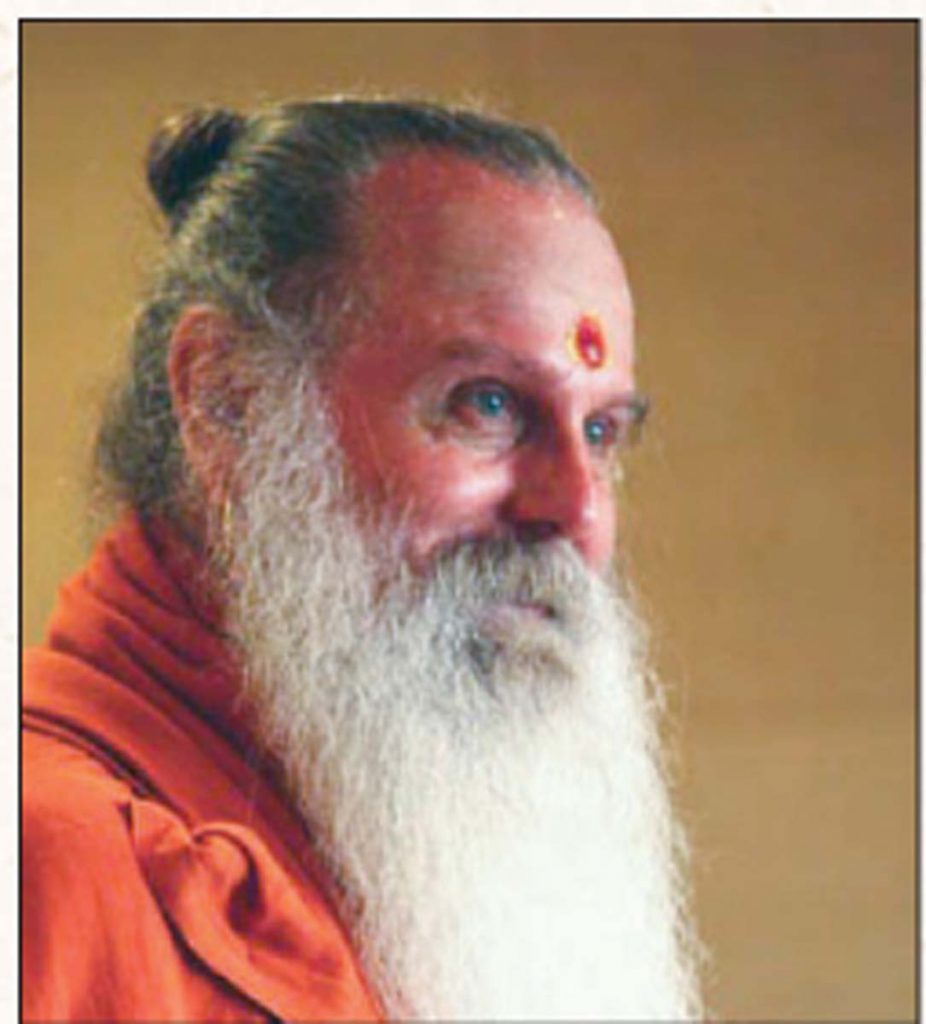

BY SADASIVANATHASWAMI, EDITOR

Prolog: Behold life’s passing into paradise. How like a languid Vedic sacrifice, with days and years poured into soulful flames in rites precise. How randomless, this intertwined device, where lice have cats and cats have mice. How bountifully it folds eternity into each tiny trice, and hugely unconcise, with fire and ice and fifty thousand kinds of rice

Deep within the granite mountains of Colorado, where you might expect to find a secret Defense Department arsenal of missiles awaiting the end of the Cold War thaw, lies another kind of stockpile. It is a dark, clinically sterile series of cold chambers, kept meticulously at -18°C and a relative humidity between 25 and 30. This is not the vault for a lethal chemical gas antidote or a vaccine for some exotic virus. These chambers, officially called the National Seed Storage Laboratory and maintained by the United States Department of Agriculture, hold one of the strategic guarantors of human survival—hundreds of thousands of seeds, including 18,313 varieties of rice. If that sounds like a lot, it’s a mere fraction of the planet’s diversity. India alone (where rice is said to have originated) had 110,000 varieties under cultivation over the centuries, according to Debal Deb, India’s leading rice conservationist. Today most of India’s rice comes from fewer than ten varieties.

Joe Biden is not spending all that money to save Uncle Ben’s precooked, short-grain, sticky white, highly polished, nutrition-free, artificially enriched rice for future generations. Uncle Ben’s is a kind of paradigm of the West’s naivete and historical neglect of rice. It opted for quick-cooking, high-yielding grains, while the East bred its strains for taste and texture. To export, the West selected for long shelf life; in the East 90% of all rice is consumed within eight miles of the fields where it is grown, so shelf life is not critical. Did you know that rice yields 6,000 pounds per acre and that 25% of the meager 20 pounds of rice each American consumes in a year is imbibed as beer or added to pet food?

“As rice goes, so will go the world’s encounter with starvation,” Dr. Charles Balach, the Texas-based guru of America’s rice breeding program, now retired, told me when I spoke with him. This is a man who knows his rice. He bred the variety that feeds most American appetites, a task that took him 8 years (15 years can be devoted to manipulating just the right combination of genes). He observes, “Rice has been cultivated for at least 7,000 years in China. Farmers spent generations selectively getting the ‘bad’ genes out of a strain, and it’s very easy for us to introduce those back inadvertently as we try to improve a strain.”

That’s exactly what happened, says Dr. Robert Dilday of University of Arkansas’ Rice Research Center. “Breeders here were going for the high yields. In the process we didn’t recognize, and thus we left out, important strengths.” Fortunately, there is a germ plasm program and collection, the one mentioned above. “There are thousands of very ordinary varieties there, seemingly useless. But they may hold some special quality we will want in the future, and it will be there. That’s the beauty, and the justification, for this massive collection effort.”

Dr. Dilday is beguiled by the variants: from the Japanese Super Rice Kernel (twice the length of the longest long grain, akin to a 12-foot-tall person) to the messy Purple Bran that when it flowers “stains your fingers like you were picking blackberries.” The new Green Super Rice (with the help of Bill and Melinda Gates and a Chinese academy) draws its hardy genetics from a mix of 250 varieties. The result is a tough rice that thrives in difficult conditions and requires no herbicides.

Americans are relative newcomers to rice cultivation, with a mere 300 years spent growing a handful of types. They are partial to wheat. Rice may sustain half the world, but in America it has been an export commodity known only in an insipid encounter with an anonymous soup ingredient or as a rare substitute for potatoes. Not anymore. There is a rice revolution going on in North America, and a smaller one in Europe, driven by the West’s newfound awareness of the health benefits of traditional Asian rices and an expanding population of rice-consuming ethnic groups. Basically, when immigration laws changed in the 1960s to allow more Asians in, millions answered the call. From Thailand, Cambodia, India, Korea and China they brought with them their culture, their clothing, their language and, of course, their penchant for rice.

When a Thai housewife cooked the Texas long-grain (which traces its roots to Indonesia, then Madagascar and thence to South Carolina in the 17th century), she was totally underwhelmed. Where was the taste? What happened to the sweet aromas she was accustomed to? Nothing. Zip. Not only that, who could eat this Yankee carbohydrate with chopsticks? Not even a black belt epicure could handle this dry grain where every pellet was an individual. In India it is said “Rice should be like brothers: close but not stuck together.” But Thais were accustomed to rices that, like Thai people, stick together (stickiness is determined by the ratio of two different starches, amylose and amylopectin). Some varieties are so sticky that if you put a chopstick in a bowl, the entire mass comes out together. Thai gourmets and gourmands love that kind. They break it off with their hands, dipping it deeply into a spicy gravy. My theory is that cultures that eat with chopsticks evolved sticky kinds, fork-eaters selected very dry specimens, and those of us who eat with our hands developed in-between varieties.

Faced with their finicky family’s famished frowns, Asian women forsook all hope of getting decent rice in the US and began importing it. Tons of it. In fact, 900 million pounds last year, nearly 10% of all the rice consumed in America. Farmers who didn’t know a Basmati—which means “Queen of Fragrance”—from a Jasmine suddenly woke up to the new reality. Asians had highly sophisticated tastes and would not settle for anything less than what grandma had cooked over an open fire. They were even willing to pay a premium for quality, a big one. Aged Basmati sells for nearly $6 a pound! The wheels of free enterprise cranked up. Breeding programs began, expensive ones focused on one goal: produce and market in the US an aromatic rice that equals that most popular of all imports, Thai Jasmine.

Thai Jasmine is the queen of short-grained sticky rices. Its smell is alluring, its texture is described as not-too-wet-not-too-dry, and its taste is savory sweet. American breeders imported a Thai strain from the famed International Rice Research Institute in Manila. They crossed it with a high-yielding Philippine stock, added a little of this DNA, a sprinkle of that and after many years celebrated the christening of Jasmine 85. It was to be the import killer. Hundreds of acres went under the Texas plow in 1989. Thai cooks by the thousands eagerly hauled home the first heavy bags of Jasmine 85, steamed it in the old country way, served it up and—“Yuck”—never went back for more.

“What happened?” marketers mourned. “What happened?” southern farmers fretted. “What happened?” rice breeders brooded. No one could explain. It tasted and smelled the same. It cooked the same. It looked the same. It was cheap. Yet it was a giant flop. Spurious stories spread that only US rats would touch it. Thai rodents preferred starvation. Well, that was the story.

This real-life disaster was a turning point in US rice consciousness. Americans, who pride themselves as the world’s most efficient rice farmers, realized they couldn’t detect differences that Asians readily perceived. They had made the mistake of not putting a single Asian on their select quality committee. “Before this experience, we didn’t recognize the subtlety of it. Or maybe we didn’t believe it. Now we believe. It started with the Asians, but now the Anglos are picking up on it,” Dr. Bill Webb confided to me.

Imports continue to grow and US researchers now respect the preferences of the strong Asian market. For a while they redoubled their efforts to match qualities found in Southeast Asia. In private they confess, “We’re no longer trying to replace the rices from India and Pakistan, but to develop a kind of poor-man’s Basmati.” Nor can they just bring seed rices in and plant them. It’s against the law. Besides, rice adapts itself to climates, to soils and weather patterns, not to mention birds, insects and diseases. All grains must be bred to US conditions. Those who touted the glories of Texas Long Grain now speak wistfully of approximating a Punjabi Basmati or an Italian Arboria. In the 1990s they were avidly breeding Purple Bran, Spanish Bahia, Black Japonica and dozens of others, hoping to capture the burgeoning niche market for specialty, fragrant rices.

Global trading agreements like the WHO and NAFTA have the plan to breed aromatic US rices, since the law now allows for import of aromatic rices in exchange for export of high-yield US rice that can feed more people and animals around the world. In most global markets, the US rice industry faces tough competition from Asian suppliers, with Thailand being the world’s largest rice exporting country, followed by Vietnam, Pakistan, India and China. Including the United States, these six countries account for more than four-fifths of the total volume of annual rice exports. For the record, our own hands-down favorite rice, one with nary an equal in all three worlds, is the ruddy, fluffy Red Country rice, known as urarisi in Tamil, grown in the fertile paddy fields of Jaffna, Sri Lanka.

Epilog: How nice is rice, especially served with spice. How it can, at meager price, twice or thrice each day suffice. How gentle and how very free from vice are those whose fodder, in the main, is rice.

This real-life calamity changed the way Americans thought about rice. Americans, who pride themselves on being the most efficient rice producers in the world, discovered they couldn’t spot distinctions that Asians could. Thank you!

The empress of sticky rices with short grains is Thai Jasmine. It has a seductive aroma, a not-too-wet, not-too-dry texture, and a savory, sweet flavor. Thank you!

When rice is seasoned with garlic powder, it becomes a flavorful, all-purpose dish that can be matched with a broad variety of foods. Garlic powder also has a delicious umami flavor.