How Going Deep Within Lets One Go Deep Below

By Mayuresh Visswanathan

If descending into the cold, dark depths of the seas doesn’t sound extreme enough for you, then you might want to try it without any breathing equipment.

Freediving is an extreme sport pushing the limits of the human body and mind underwater, all without the use of scuba gear. Brave freedivers—on one breath—can dive hundreds of meters at a time, a feat requiring complete mastery of themselves to ensure a safe dive. Within the past 40-50 years, yoga techniques and practices have upgraded the sport, allowing divers to greatly increase control of their diaphragm, breath and mind.

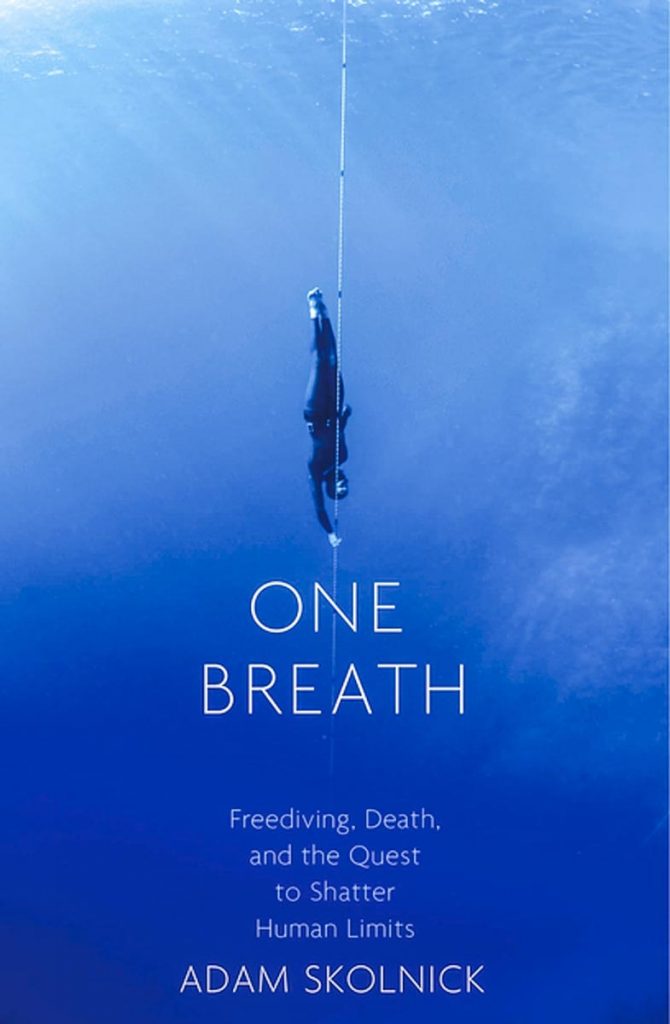

To understand the use of yoga in freediving it’s essential to delve into the sport’s nuances. To learn more I read Adam Skolnick’s book, One Breath: Freediving, Death, and the Quest to Shatter Human Limits. While it may sound simple, there are over ten distinct competitions testing ability to hold one’s breath for the longest time, to cover a specified distance in the shortest amount of time and to dive as deep as humanly possible. Some disciplines, such as No Limit, allow divers to use fins, weighted sleds for descent, and lift bags or counterbalance pulley systems to aid in ascension. Yet, many would agree that the ‘purest’ discipline is Constant Weight Without Fins, in which a diver can use only their body, optional weights and a wetsuit to complete the dive. The world record for this finless event is an astonishing 102 meters or 335 feet, equivalent to diving the height of a 30-story building.

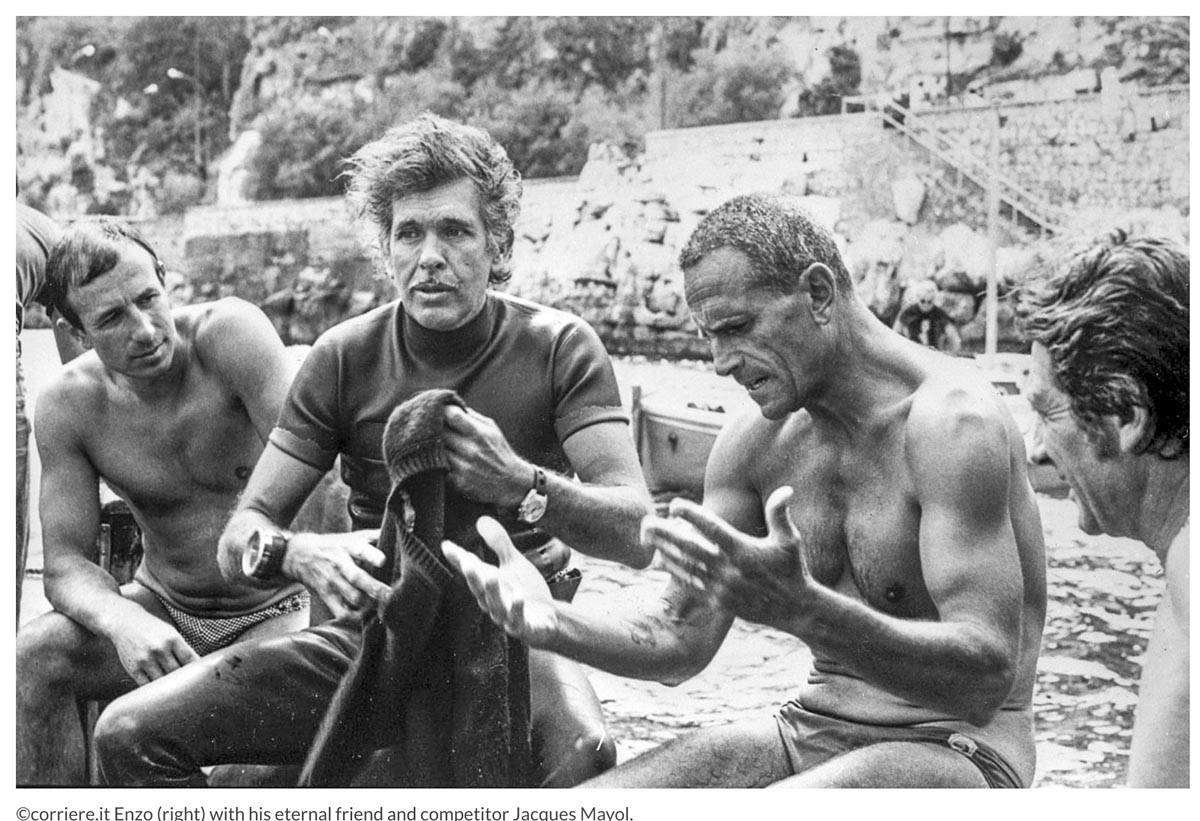

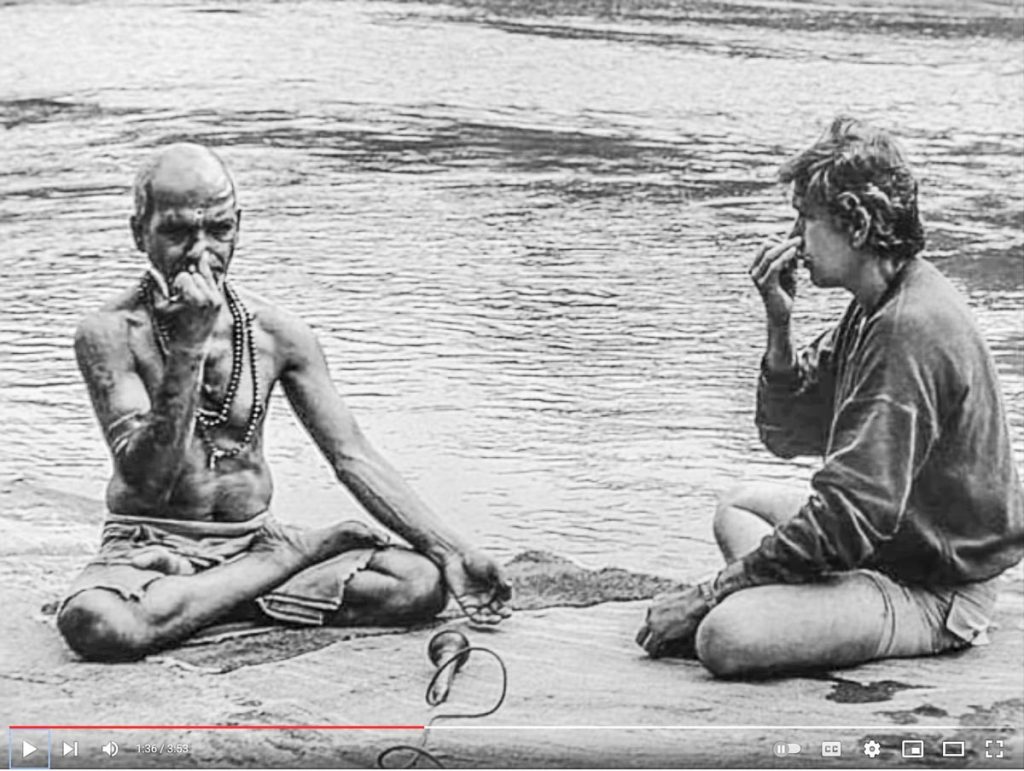

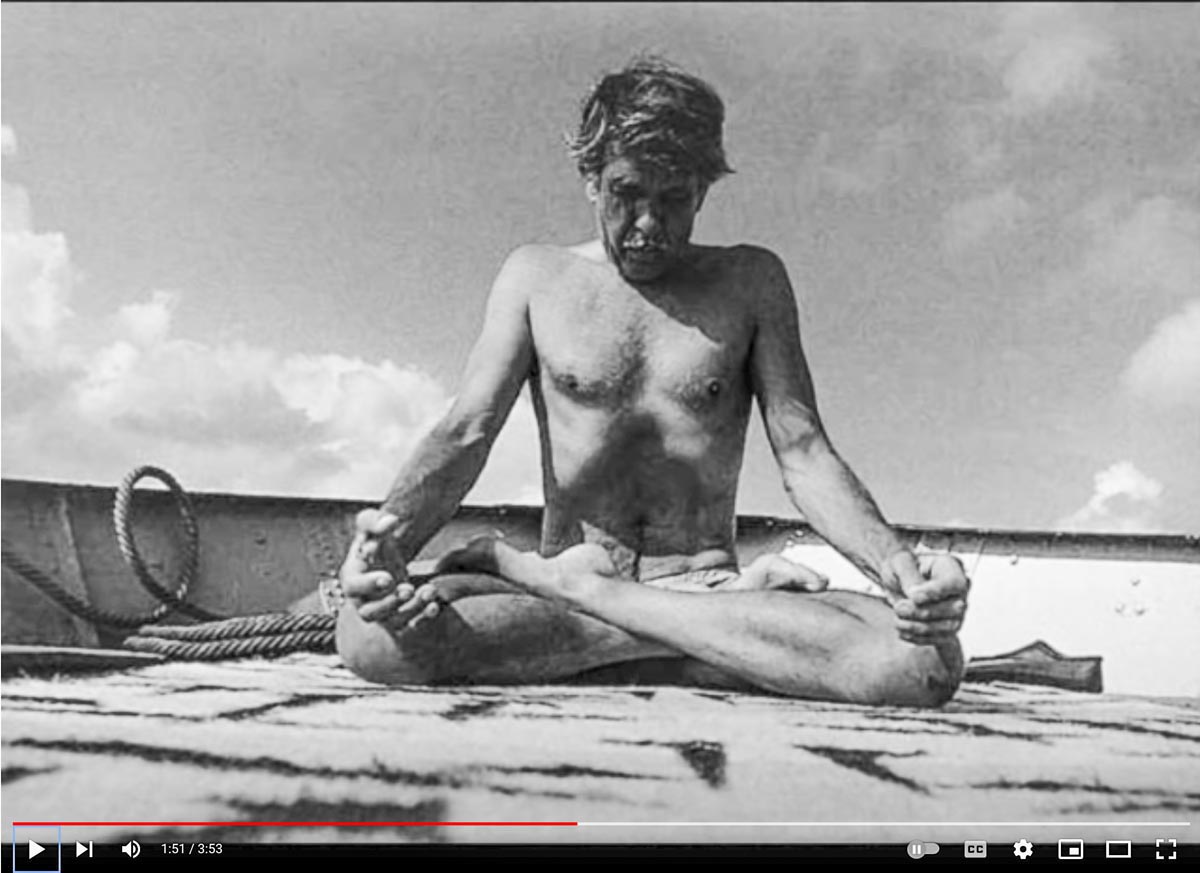

Competitive freediving started in the late 1950s, dominated by daredevils trying to push bodily limits. There wasn’t much emphasis on breath or mind control; it was a battle of reckless bravery. Enter Jacques Mayol. As a child, he was fascinated with dolphins and dedicated much of his life to emulating their behavior by pushing physiological and mental limits in the water. Mayol is credited as the first to integrate yogic philosophy after traveling across India to learn tools for controlling his diaphragm and mind. With pranayama and various asanas, Mayol set records and permanently changed the sport. He was pivotal in the sport’s transition to a practice more focused on the control of body and mind rather than pure fearlessness.

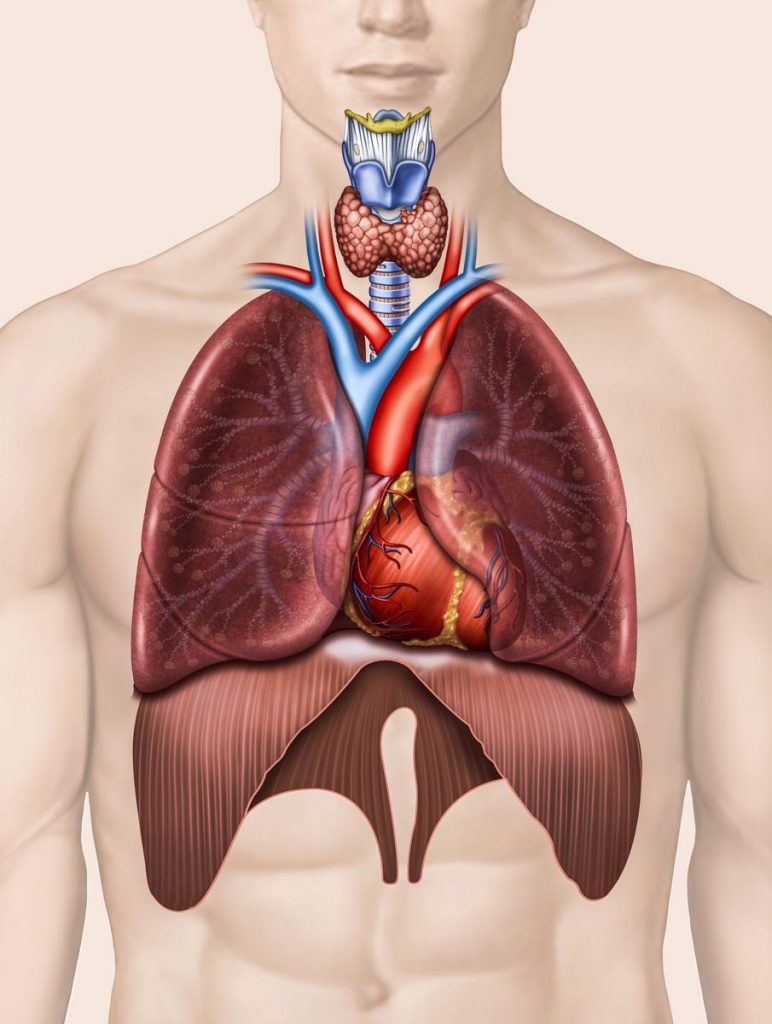

Yogic training for freediving emphasizes diaphragmatic control. This thin, dome-shaped muscle below the lungs and heart is responsible for inhaling and exhaling; thus, control of it allows for breath control. Nearly all freedivers practice specific asanas such as the upward abdominal lock, or uddiyana bandha. The abdominal wall is sucked up as high as possible, creating a vacuum in the chest cavity. The organs in the abdominal area move up into the chest cavity and the diaphragm flattens against the spine. This exercise not only stretches the diaphragm, it allows for a better mind-muscle connection. Masters can “even ripple it in waves like a contortionist” according to Skolnick. Serious freedivers gain such incredible control of their diaphragm that they can pack air into the small alveoli (lung’s air sacs) behind the shoulder blades. Skolnick said in an interview, “It requires years of slow training, building more and more depth and flexibility” to integrate yoga exercises with the physical practice of freediving; hence athletes dedicate tremendous time and effort to master their craft with yoga and intercostal muscle stretches pioneered by Mayol to increase rib cage flexibility, allowing them to withstand intense barometric pressure and fill their lungs to at least 120% normal capacity. They learn to move air from the lungs into the mouth and gradually funnel it into the sinuses through the soft palate in order to equalize on the way down.

Beyond 30 meters, the pressure gradually compresses the lungs to less than a quarter of their normal size. Displaced air moves to dilated blood vessels in the heart and brain. The spleen also contracts, sending a fresh supply of red blood cells to convey oxygen more efficiently to the heart and brain. The human skeleton avoids total collapse at these depths by involuntarily constricting blood vessels in the limbs, shunting blood into the body’s core, which acts as a vacuum filled with fluid to prevent further compression. Similar physiological responses occur in aquatic mammals such as sea lions during deep dives. Far down, divers’ heart rates can decline to 20-30 beats per minute, which is less than half the average human pulse rate. Such a low pulse rate in healthy individuals has only been recorded in monks during periods of deep meditation. These physiological changes together are called the mammalian dive reflex.

To help overcome fear during training, yoga techniques are accompanied by submerging one’s face, which stimulates nerves around the eyes and sparks the dive reflex. With conscious development of the reflex, learning to lower the heart rate even before descending, one can dive deep without feeling anxiety or the slightest urge to breathe. It’s not just fear to overcome during apnea. Thorax compression, lactic acid and CO2 buildup cause strong pain. Pool training builds tolerance through disciplines of swimming as many laps as possible with and without fins on one breath. Starting in the last decade after wide dissemination of a new equalization technique, many newbies have gone very deep too soon, resulting in a proliferation of lung squeeze, in which capillaries hemorrhage blood into the alveoli, often causing damage to the tissue and causing one to spit up blood.

While the physiology is impressive, the experience itself is awesome. Skolnick shares in his book: “As you go deeper and deeper, the ocean squeezes you. You feel held or cradled by the ocean. All of that gives a sense of merging with something much greater—you feel miniscule in this big blue amazing ocean.” In a way, freediving engenders oneness with an all-pervasive consciousness. The diver is akin to a drop of water within the ocean of consciousness. As he plunges deeper, increasing pressure forces him to remain calm and surrender. Bodily squeeze gets so tight that the divers often describe feeling a distinct merge into a singular consciousness and a complete “loss of I.” Thus, the water drop and ocean become indistinguishable; they become one. The spiritual aspect of freediving is similar to the experience of samadhi in deep meditation, both of which are fundamentally controlled by breath. Just as samadhi is a state of enlightenment, of union, the experience of merging with the ocean runs parallel.

Yoga is indispensable for a maximized body and calmed mind. To votaries of freediving it’s not just another activity. Rather, Skolnick explains, “There is a reverence and love for the ocean. It’s more than just a sport. It’s a way of life.”

The Deepest, Longest Dives

The excerpts below by Mark Murphy are reprinted with permission from Oyster Diving. View his full blog post at https://oysterdiving.com/blog/freediving-record/.

Herbert Nitsch is named as “the Deepest Man on Earth” and for a very good reason! He is a multiple World Champion and the current holder of the World’s Freediving Record. Nitsch (photo right) holds 33 world records and can hold his breath for more than nine minutes! How long can you hold your breath?

There are only four freedivers in the world who have gone beyond 560 feet and two divers died trying. Nitsch is the world’s only diver, so far, to have gone beyond 700 and 800 feet [sufffering a major stroke in so doing}. It has been the determination of passionate freedivers, pushing against the tide of nay-sayers, who have made what once was thought impossible, possible! Let’s hear from some of the deepest divers.

In the early days, scientists and physiologists were convinced that if humans dove beyond 100 feet, their lungs would collapse. They had carried out extensive research and worked out what they could about how the human body works and the effect immense amounts of pressure can have. But freedivers decided to risk it anyway and today they are swimming over seven times deeper than the depth initially recommended.

Martina Amati, a free diver, has tried to explain the mindset when taking up the challenge of this extreme sport. She told The Conversation, “There is an element of physicality but it’s mainly mental. That’s what is incredible about freediving. It’s not about your physical ability, but about your mental skills and training. You need to let go of everything that you know and everything that makes you feel good or bad. And so it’s a very liberating process. But equally you need to stay completely aware of your body and where you are, entirely in the moment.”

Freediving is one of the first underwater sports to come into existence. It has been around for a very long time. Traditionally, people used to freedive for food, sponges, coral and pearls. Free-diving only reduced after technology advanced, introducing us to more convenient fishing and foraging methods. However, in ancient cultures freediving was incredibly common and sometimes to around 50 meters on one breath!

Today, freediving is a competitive activity and expert divers can last for up to 22 minutes submerged under the water. Stig Severinsen holds the Guinness World Record for the longest freedive under ice on a single breath of air – and he earned it while in Speedos!

Sportsman James Nestor related to National Geographic, “Something amazing happens the second we put our faces into water. Our heart rates lower about 25 percent. Blood begins rushing from our extremities into the core. The mind enters a meditative state. At around 250 to 300 feet, the heart rate of some divers has been recorded at about 14 beats per minute. That’s about a third of a coma patient’s. It shouldn’t support consciousness according to physiologists. And yet, deep in the ocean it does. But no one knows exactly how.”

Freediver Jody Fisher shared, “When you’re doing deep diving, you might be able to see 40 or 50 metres and there’s not really any sound. The only thing you probably will be hearing is your heartbeat. It feels like time has stopped.”

About the author

Mayuresh Visswanathan is currently an undergraduate student at UC Berkeley, with interests in the environment and sustainable business. He enjoys growing aquatic plants, woodworking, and staying active.