The caves of Ellora, culminating in the famed free-standing Kailasanatha Temple, were hand-carved from a mountain during a period of 400 years

By Anne Petry, India

Monolithic rock religious constructions are found in only a few places in the world: the rock-hewn churches of Lalibela in Ethiopia, the Great Sphinx of Giza in Egypt and the Kailasanatha Temple of Ellora in India. When a building is carved or excavated from solid rock, to which it remains attached at the base, it is termed “monolithic architecture.” The Kailasanatha Temple for God Siva is the largest such structure in the world.

The excavation of caves and their elaborate adornment are closely related skills. In India, the first excavations of rock caves date back to around the third century bce. The Lomas Rishi cave in Bihar is an example, and later, in the west of the country, caves at Karle and Bhaja, the famed Ajanta Caves and the Elephanta Caves off Mumbai. Through several distinct periods over time, techniques improved, new concepts emerged and the work was refined. Ellora, and the Kailasanatha Temple in particular, are the apogee of monolithic architecture—the culmination of centuries of evolution in Indian rock temple architecture, successfully synthesizing the long tradition of rock sculpture in Western India, Southern India and the Deccan Plateau.

Although I had already traveled quite a bit in India, having seen the Taj Mahal, Hampi, Mahabalipuram and more, I wondered why many friends were so insistent that I visit Ellora Caves. I like to be surprised by places on my travels, so I decided not to do too much research. I simply followed their advice to go and see—and I discovered Ellora to be one of the iconic archaeological wonders of ancient India.

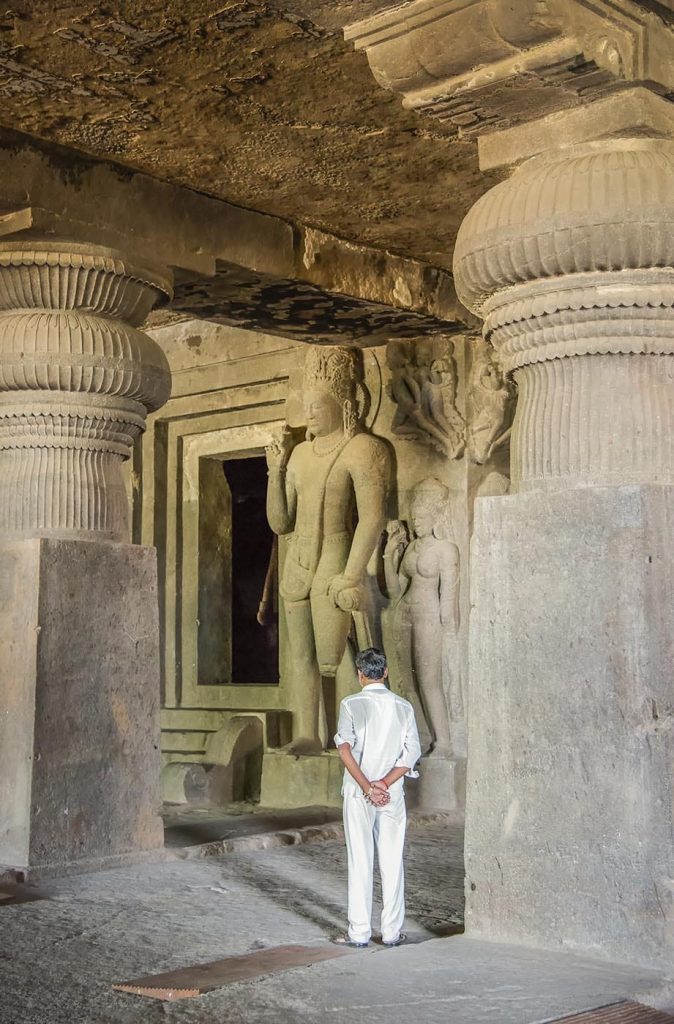

When I arrived at Ellora Caves, my first impression wasn’t “How beautiful! “ nor “How old it must be!” but rather, “How could an ancient civilization have built such a majestic place?” I wondered how it was possible that centuries ago they had the physical ability, artistic talent and technology to create a marvel like the one before my eyes. Adorned corridors, breathtaking chambers, gigantic statues, exquisite carvings and precious murals—all created with nothing more than chisels, hammers, willingness and patience.

Consider Kailasanatha. Who conceived and then executed the fantastic idea of tackling a mountain, removing tons of rock bit by bit, starting at the pinnacle and working down to the base, over hundreds of feet? Instead of doing what was already known, like stacking stones and going from bottom to top to create a monument, they decided to do the opposite and go from top to bottom by chipping into the mountain’s heart by hand. Just as India’s current-day stone carvers approach the carving of a relatively small statue as a process of revealing the already finished form by removing the unnecessary stone around it, these architects set out to reveal a huge temple from a mountainside.

Ellora’s caves were sculpted over a period of more than 350 years, from the sixth to the tenth century ce. The scale of work and continuity over time call to mind other astonishing human projects: China’s Great Wall, Cologne Cathedral and Egypt’s pyramids.

The endeavor required patience and motivation, both for the reigning dynasties to ensure continuity in the realization of this project, and for the workers, men and women who spent their entire lives on these titanic creations. Know-how was passed down from father to son and grandson with one common goal: the splendor of Ellora. The workforce came from different parts of India; there is an obvious blend of different traditions and a wide range of typologies and construction techniques here. The site traces the evolution and innovations of cave temple architecture from the fifth to the tenth century.

Visiting Ellora

Ellora Caves is located in the western Indian state of Maharashtra, 19 miles from Aurangabad and 202 miles from Mumbai. The road to the caves passes through numerous villages offering magnificent scenes of rural life, then crosses a vast plain. Ellora lies in a relatively flat, rocky region of the Western Ghats, where ancient volcanic activity has created multi-layered basalt formations known as the Deccan Traps. Once there, you climb up a rocky spur to discover over a hundred caves on a cliff-side some 320 feet high and 1.2 miles long. The 34 caves open to the public are more or less deep, more or less elaborate. Each stems from one of India’s three great religions of the era: Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. Follow me on a tour of those precious caves to find some explanations, but also some of the enigmas that remain unexplained to this day by archaeologists and historians.

The caves and the temple have a fortunate history. During the time of extensive Muslim invasions and destruction of thousands of temples, the area was no longer on the common trade routes. Apparently, few attacks occurred here, though there is obviously deliberate damage to many statues and carvings. The temples of Khajuraho were similarly out of the way during this time and therefore are today mostly intact. Ellora Caves was listed as a World Heritage Site in 1983 and is protected by the Archeological Survey of India. Unlike many other ancient sites, it has never fallen into oblivion. It attracts thousands of pilgrims every year—to which we can now add the many foreign tourists.

Soon after arriving at the site, I met a German couple, early birds who were leaving just as I was beginning my discoveries. Both were very enthusiastic, saying: “This is one of the most spiritual places we’ve seen in India.” Having just arrived, I had no idea what they meant, but I was soon to find out.

The entrance to the site is at the Kailasanatha Temple (cave no. 16), but in my opinion, starting the visit with cave no. 1 would make more sense, as the numbering of the caves follows the supposed chronological order of their construction.

The caves are numerous and not all of the same level of interest. In addition to the must-see Kailasanatha Temple, I would recommend visiting caves no. 10 (Vishvakarma—Buddhist), 15 (Dashavatara—Hindu), 29 (Dhumar Lena—Hindu) and 32 (Indra Sabha—Jain).

Those who have a whole day to explore the site will also want to look at the other caves. I recommend finding an authorized guide who will help you understand the symbolism of the enigmatic sculptures and fascinating murals. The guide will also explain in greater detail that the earliest caves were Buddhist (12 caves built between the 5th and 7th centuries), followed by Hindu (17 caves built between the 8th and 10th centuries) and finally Jain (5 caves built between the 9th and 11th centuries). Each cave features statues of Deities and divine figures that prevailed during the first millennium, and many of them were occupied by monastics of each religion mentioned.

The period from 300 to 1000 ce was a golden age for India. It was a time when an estimated one-third of the world’s population lived in India, a time when Hindu tradition, culture, scriptures and the Sanskrit language linked people all across this vast and fertile subcontinent. Indeed, the Sanskrit language, with its many treasures of religion, philosophy, law and epics, spread not only throughout India, but also across most of Asia. Four major types of evidence—archaeological studies, official inscriptions on stone and metal, coins and contemporary texts—show that for over 1,000 years, India was the richest region on the planet.

Considering the long history of building in Ellora, one might wonder why all the dynasties, major and minor, that controlled the region were so keen to build on this particular site. The reason may be simple: Ellora Caves were an integral part of the aforementioned prosperity. In addition to being used as temples and resting places for pilgrims, their strategic location on an ancient South Asian trade route made them an important commercial center in the Deccan region in their day. This was also a time when many Hindu saints of the Bhakti Movement preached the importance of devotion to God, popularized sacred stories, songs and devotional worship, and enabled devotional Hinduism to spread throughout the subcontinent.

As I was resting and enjoying a shady spot, I saw an Indian man apparently filming himself with his phone. Watching him with his stylish cell phone and selfie stick, I couldn’t help smiling at the contrast between this ultra-modern young man and the ancient setting. When I later approached him, he explained that he was a YouTuber and a great lover of history, and that the Ellora Caves were on his list of ten sites to discover in India. He considered it a privilege to have access to the caves, which allowed him to immerse himself in the history of his country. He wanted to share this privilege with those who live too far away or simply can’t visit Ellora, so he made a short video to post afterwards on social networks.

I must admit I was surprised by his respect for his ancient civilization, and I was reassured to see that despite the changing times, with all it implies, the younger generations continue to be fascinated by the work, strength and skills of their predecessors.

Exploring the Site

The Hindu caves, mainly dedicated to Siva, are typically the most popular with visitors, offering sculpted ensembles of the highest quality. These chambers feature absolutely remarkable workmanship, with ornate facades, stunning naves, superb friezes, magnificent bas-reliefs and thousands of finely chiseled carvings. This composition of niches, galleries, openings and assembly halls of unparalleled richness is like an open book on a bygone era for travelers and pilgrims to discover during their visit.

Ellora is also a journey into Hindu cosmology. From one cave to the next, engraved in stone, you can admire numerous sacred scenes: Siva marrying Parvati, Siva slaying the demon Andhaka, Siva and Parvati playing dice, Brahma and Vishnu taking part in a cosmic dance, Vamana liberating the world and more.

The Amazing Kailasanatha Temple

The jewel of Ellora, for its beauty and size, remains the Kailasanatha Temple. Its construction began in the 8th century, when the Rashtrakuta dynasty controlled Southern India, and religion, trade, science, technology, literature and art were flourishing. It was entirely carved from top to bottom out of a single hard basalt hillside using iron hammers and chisels—not by stacking stones. There is no margin of error when removing stone from the finished product, so precise planning and layout were required for the work to progress successfully.

It is estimated that 400,000 tons of stone were removed to reveal the temple and create the numerous chambers both inside and in the adjacent cliffs. At 108 feet high, the Kailasanatha Temple is the largest monolithic sculpture in the world. Its 98-fo0t-tall central pillar makes it all the more fantastic. The excavated area measures 276 feet long, 154 feet wide and 108 feet high, totalling 170,000 cubic yards that the founders faced when they started work on the site.

The volume extracted is greater than the monolithic temple that resulted from these extractions. Moreover, it is said to have taken just 18 years to carve—which would have required thousands of workers, if not ten of thousands. For those interested in history and technical information, there are so many figures that could be mentioned about this particular temple, such as the number of chambers or the number of statues, but in the end, I feel that the beauty of the Kailasanatha Temple lies more in the poetry of its delicate construction, and I think it is best to just let yourself be inspired and transported by this out-of-this-world edifice.

The temple’s architecture and sculpture clearly show the presence of craftsmen from Chalukya region working alongside men from the Pallava and West Indian regions. The striking contrast between the hillside’s raw mass and the finesse of the carvings that adorn the temple demonstrates the knowledge and expertise of these masters.

The temple’s name, Kailasanatha, “Lord of Mount Kailash,” refers to Himalayan Kailash mountain where Siva resides. It is said that Kailash mountain is represented by the central temple, to which the builders wanted to give the shape of a chariot; the missing wheels of this chariot were replaced by enormous elephants ready to pull said chariot.

The two staircases leading to the temple’s main hall are flanked with narrative episodes from the Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. This temple, dedicated to Siva—which also has a few shrines dedicated to Vishnu—is a rich compilation of Hinduism, since most of the key epic scenes are engraved here.

While the complex sculptures that adorn the temple are in the Dravidian style typical of Southern India, one finds here and there traditional figures from other regions of the world such as the sphinx (evidence of trade with Egypt between 700 and 900 bce) and the dragonfly (Chinese influence, recalling the passage of Silk Road caravans).

I very much enjoyed watching Indian families wander from cave to cave, admiring this great part of their cultural and religious heritage. Here and there, parents would briefly explain to their children the meaning of certain scenes they were looking at. And even if they didn’t know the whole story, I thought it was marvelous that the transmission was made through a site where there were intense moments of life, rather than through the inanimate pages of school books. How lucky these children—and I—were to have access to an ancient monument in such good condition!

Final Thoughts

If I had to describe the Kailasanatha Temple in just a few words, I would say that it remains unsurpassed as the largest and most grandiose monolithic stone masterpiece in the world, and that it now constitutes one of my unforgettable memories of India.

The prosperity, stability and religious harmony of early India gave rise to remarkable philosophical, literary, artistic, scientific and technological achievements, of which the Ellora Caves are one. And despite the substantial damage to the carved murtis, the disappearance of some of the paintings (largely due to the wood-fired cooking used in those days) and the collapse of the facades of some of the caves, the site remains absolutely magnificent and fascinating.

The ideal times to visit are from October to February and June to September, when the weather is pleasant. The more adventurous can also visit out of season. I visited Ellora Caves in May—when high temperatures demotivate the crowds—and it was fantastic.

In addition to its incredible technical features, this is perhaps where the magic of this archaeological marvel lies: it allows us to travel back in time. I enjoyed going quietly from cave to cave. It was the best way to imagine and somehow visualize what life might have been like back then: a monk reading holy scriptures here, another quietly sitting and meditating there, others chatting while walking to the Kailasanatha Temple. The Ellora Caves site is a gateway to a distant and fascinating era.

Although it’s not easy to put into words the energy, or what we might call today the “vibes” of a place, so subtle and personal are they, walking through Ellora, I felt a powerful energy and at the same time a profound serenity. It may seem contradictory, but when you think about it, these caves have received so many monks and pilgrims, so many religious rituals and devotion, all of which has enriched this place in a way that I was able to feel deep inside.

My wish for all those who visit Ellora Caves is to see not only the grand dimensions, the beautiful murals and the stunning sculptures, but to deeply experience the holiness of the site. To me, that is the most precious gift you can receive from this visit: the feeling that your inner sacredness is connected to universal sacredness.

About the Author

Anne Petry is a French photographer focusing on Indigenous populations. Her nomadic life takes her all over, from the Shamans in Amazonia to the Hindu priests in India. She is passionate about people who keep alive their beliefs and traditions. Contact Instagram: annepetryphotography