By V KALYANAM, Chennai

Gandhi’s day began at 3:30am sharp. When I was with him, in 1947, the 78-year-old got up by himself, requiring no alarm to rise at that early hour, and woke up his associates who slept in the same room. His work spot also served as his bed. He never used a table, chair or cot. He denied to himself all such comforts that the poor in India could not afford. He gave up clothing and put on only a loincloth. He remained bare chested most of the time, using a shawl only in cold weather.

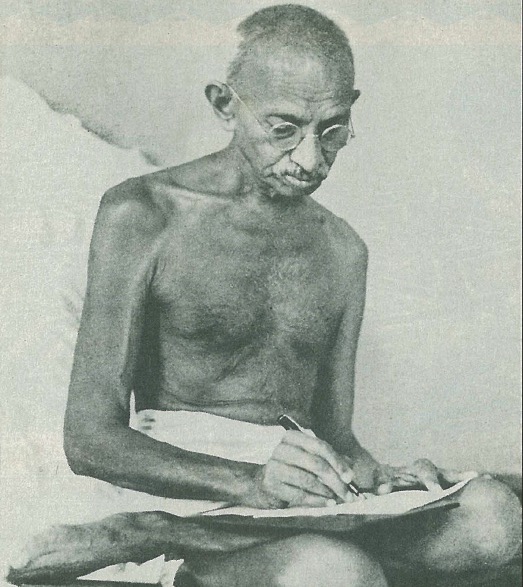

He sat cross-legged on the floor on a thick cotton mattress with a pillow at the back to recline upon. Foreign visitors who were not used to squatting on the floor were offered chairs to sit. They would always decline, preferring to sit on the floor while conversing with Gandhi.

In front of Gandhi was a small portable desk containing stationery and important correspondence requiring his personal attention. On top of the desk was a replica of the three monkeys, to remind that one should not speak, hear or see evil. By his side there was a spittoon, a bottle of water, a basin for a face wash and a towel.

Prayer, according to Gandhi, was the key of the morning and the bolt of the evening. Thus, after his morning ablution, he commenced his day’s work with prayer recited by us from all major religions. This took about half an hour. He then had his first meal of the day–a large tumbler full of hot water mixed with a tablespoon of honey.

He then perused the correspondence placed before him. He observed silence every Monday. On these days he kept himself fully engrossed in replying to letters and writing articles in his own hand in English, Hindi or his mother tongue, Gujarati. We avoided granting any appointments for visitors on this day. If Gandhi had anything to convey to me or anyone else, he wrote the message on a slip of paper.

On other days of the week, it was my duty to sit by his side after the early-morning prayer and take instructions. I typed in English whatever was dictated to me. He approved and signed letters before dispatch. His articles were always published first in his weekly Harijan. This was brought out in English, Hindi and Gujarati.

He had his half-hour morning constitutional at about 6am, resting his hands on the shoulders of his two grandnieces who walked on either side. These two girls looked after his personal comforts and needs such as serving him food at the right time, brushing his dentures, giving him a massage, helping in his bath, shaving, etc. After the morning stroll, he stretched himself for half-an-hour for a body massage with mustard oil mixed with lemon juice. That over, he had a hot-water bath and got ready by 9am for his lunch which consisted of saltless vegetable soup, boiled vegetables, thin wheat pancakes and goat’s milk. Even while eating, he met VIPs. At 11am he again had a short nap, then resumed writing or meeting visitors. He had fresh fruit juice at 2pm and then spun cotton for half an hour. He then lay down on the mattress as one of the girls applied a wet mud pack on his stomach. At 5pm he had his dinner, which was the same as his lunch. He sustained himself on this bland food for years. I never saw him take salt, spices or sweets at any time.

Soon thereafter he held his evening prayer in public. A large number of people came to participate, anxious to hear his post-prayer speech. It usually centered round the important political developments of the day, and Gandhi informed the listeners of his discussions with VIPs. When there was nothing particular to be conveyed, Gandhi dwelt on sadly neglected subjects like sanitation and cleanliness, the need to preserve communal harmony, the evils of racing, betting, smoking, drinking, etc. He also took the opportunity in these discourses to have a dig at the Indian Government for their “extravagance and frivolous public expense” in erecting his statue and conducting lavish celebrations at a time when many people were homeless and starving. After the prayer, Gandhi had a stroll for half an hour with VIPs having an appointment. He retired to bed at 9pm unless some very important work held him up, which was rare.

Gandhi received nearly 75 letters and telegrams every day from all over the globe. One of my duties was to peruse these letters and use my discretion in placing before him all such correspondence which I considered necessary for his attention. Most of the letters were in English. Ten percent were in Hindi, Urdu and other Indian languages. A few were in German, Italian or French.

Gandhi laid great stress on economy. All correspondence that was not considered essential for preservation was converted into writing pads of different sizes, and the blank page on the reverse was used by all of us for writing. Similarly, envelopes were slit open and converted into writing pads. It was on such one-side-used paper that Gandhi wrote the letters and articles I had saved.

The public work Gandhi was engaged in required him to visit various parts of India. His two grandnieces, myself, a lady doctor and a senior secretary were his constant companions. We accompanied him in all his travels. None of us stayed in any hotel.

For long distances we traveled by train in the third class (now abolished). Since third class was always overcrowded with travelers from the lowest strata of society, the railway administration placed a full third-class compartment at Gandhi’s disposal in which we alone traveled.

Gandhi’s travel plans were widely publicized in the press, and so huge crowds of admirers would throng railway stations to have his darshan. Crowds contributed cash and gifts in kind liberally to Gandhi. All these were accepted and kept in the compartment. By the time we reached the final destination, the compartment was full of hand-spun cloth, food, etc., which were given to local welfare organizations.

Gandhi made a vast tract of donated land in Wardha, central India, his headquarters. He named it Sevagram, “service village.” He intended to make it a model self-contained township. India’s leading industrialist, Mr. Birla, placed huge funds at the disposal of Gandhi. A number of people from different walks of life offered their services to Gandhi. Among them were expert doctors, agriculturists and craftsmen. They lived with Gandhi in mud huts with thatched roofs. Free boarding and lodging was all they received for their services.