Last summer, the Hindu American Foundation conducted its Next- Gen essay contest, soliciting original essays from youths 17-28 years old answering the questions: Why is a Hindu American identity important? How can you advocate for this identity in public policy and your private life? How can Hindu American advocacy be benefi cial to our American society? Enjoy excerpts from three of the winning entries below. The originals can be read at www.hafsite.org/nextgen.

My Battle Within: The Identity Crisis Of a Hindu Soldier in the US Army

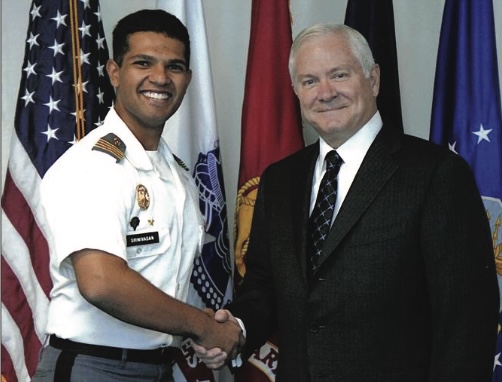

BY R A J I V S R I N I VA S A N

The barrel of my m4 assault rifle is slender, black and cold. The rippled plastic grips fit ergonomically to a mission driven hand, one that aggresses to protect a nation and way of life. With each trigger squeeze, a 5.56-caliber bullet breaches the muzzle at 2,900 feet per second with the sole purpose of taking another’s life. Despite its lethality, this weapon is only a piece of metal. It is nothing without the mind and heart of the soldier perched behind it. As I don my body armor, grab my weapon and prepare to lead my platoon of 32 soldiers into Afghanistan, I hesitate. I turn to the portrait of Krishna in my office and demand of him, “What is the worth of this fight? Is it worth our limbs, our lives or the heartbreak of our parents? What cause is so important as to merit the coming violence?” And so begins my war within: the quest for an identity.

Like most Indian youth in the US, I faced the inner conflict between my Indian and American identities. At home, I watched Bollywood movies and prayed to Hindu Deities; but at school, I spoke English, played football and did whatever I could to emulate a typical American childhood. I felt pulled in two directions: one identity abandoning my Indian heritage, the other neglecting my American way of life. Thus, I went through my most formative years without knowing who I was, nor what I stood for.

As high school came to an end, I hastily made the decision to attend the US Military Academy at West Point, but did so in vain. At the time, I was not sure about being an Army officer. I was just looking for a shining star for my resume. I was looking for a way to pay for college. Perhaps on a deeper level, I was looking for a sense of belonging. I wanted an identity to which everyone in my immediate surroundings could relate and respect.

The US Army is a rare home for an Indian immigrant, but no other endeavor has ever given me the professional and spiritual fulfillment than the experience of military service. The Army challenged my most extreme patriotic influences against my peaceful Hindu beliefs. How could I serve patriotically as a US Army Officer, owning the responsibility of waging war against our national enemies, but remain a man of the Hindu faith believing in the peaceful coexistence of all beings? This was a deep philosophical confrontation, but I accepted it with resolve.

Through days of wet, cold, hot, humid, tired and hungry, I maintained a vegetarian diet. After a long day of military training, I returned to my barracks to indulge myself in the poetry of the Bhagavad Gita. I found solace in Arjuna’s struggle as a shamed warrior fighting against his blood. I found strength in Krishna’s assertion of conviction and discipline. I found that, though typical Hindus and soldiers lead vastly different lives, both share a common purpose: to serve a higher calling for good. Thus, there was no need for a struggle between my American and Hindu identities; rather, finding strength in one made me stronger in the other.

My Hindu American identity is now a defining part of my life. As Arjuna beckons of his charioteer, “How can I wage war against my family? I would rather surrender, than commit such atrocities,” Krishna affirms that it is our duty as Hindus to do what we believe is right, regardless of the opposition. When peaceful attempts to reconcile fail, we must be prepared to defend the values in which we so wholeheartedly believe. It is this reasoning that convinces Arjuna to fight to protect his kingdom. It is this reasoning that Gandhi used when supporting the British Army’s aggression against the Nazis in World War II. This reasoning is why I feel so compelled to defend this nation, that has given my family countless gifts, against those who wish to do it unnecessary harm. I do not fight in spite of my religion. I fight inspired by it.

The importance of the Hindu American identity extends beyond a vague resolve to fight for what you believe in. Each of us is faced daily with moral challenges in this country, and our reactions to them define our spiritual resolve. This nation is in an ethical crisis, from the poorest of American ghettos through the wealthiest of corporate banks. Hindu Americans are a dominant source of influence, wealth and intellect in this nation, so what does it say of our personal constitutions if we tolerate the ethical degradation around us? We have the means to drastically improve the ethical standards in this country. We owe it to ourselves as Hindu Americans to defend, as Arjuna does his kingdom, the moral foundations which have made this country a haven for religious and ethnic tolerance. We could collectively sit on the sidelines and criticize our leadership as many Americans do. But if we aspire to follow Krishna’s guidance, it is our duty to proactively defend the integrity that upholds our great society. This is the new importance, the calling, of the Hindu American identity: inspired by our faith, we must actively rebuild our nation’s character and preserve it for our posterity. So I ask of each Hindu American, what have you done to make America stronger for our children?

rajiv sriram srinivasan, 23, is a Lieutenant in the United States Army serving as a Platoon Leader for Attack Company, 2-1 Infantry out of Ft. Lewis, Washington. He was born in Chennai and raised in Roanoke, Virginia, by his parents Gita and Rajagopalan. Rajiv is the founder of the nonprofit Beyond Orders (www.beyondorders.org), a website that connects soldiers in war zones with NGOs in the US to meet the humanitarian needs of the Iraqi and Afghani people. Rajiv remains a devout Hindu and a vegetarian. E-mail: believeinrajiv@gmail.com

The Hindu American Identity: A Melting Pot within a Melting Pot

By Purnita Howlader

Superman, wonder woman, spiderman and me. what do these four people have in common? While I may not fit the mold of these characters, we all have a major commonality. I feel that I’ve been leading somewhat of a double life for a long time, and it has not been until recently that I’ve come to accept as well as try to fuse my two worlds together. My “double life” stems from being an ABCD, or “American Born Confused Desi.” This is a term that refers to people of South Asian descent who were born and live in the United States. The confusion is regarding identity: as an ABCD, I am constantly battling between two cultures, the culture of my parents and that of the society in which I have been raised. Not only are ABCDs confused about their identities, so also are FOBs, or “Fresh Off the Boat” Hindu immigrants to America.

Between these two groups, there is a lot of disparity as to what a Hindu American identity is or what it should be. America is known as a melting pot of cultures, ideas and languages. The Hindu American identity is itself a melting pot, as there are so many variations of the religion and of the people who practice it.

As an ABCD growing up in a predominantly Caucasian suburb of the Minneapolis/St. Paul area, I naturally made friends with peers with very different cultural and religious upbringings from my own. I recall feeling left out when my friends went to church camp each summer and when a large percentage of my classmates showed up to school with bracelets proclaiming their faith. I saw that my faith didn’t have such large-scale organized events or gimmicks to latch onto. My family follows Hinduism, which is the world’s oldest and the third most practiced religion. However, as a native English speaker, it was not very easy for me to practice the religion, due to language barriers. I was taught the basic beliefs, but never fully made the teachings a part of my daily life as I imagine I would have if I had been raised in India.

As an adult, I’ve begun to realize the importance of learning more about the Hindu faith and maintaining it as a part of my way of life. As a Hindu American, I’ve been exposed to other religions throughout my education, most notably Christianity and Judaism. In America, Hinduism has always seemed to blend into the background, willing to succumb to the religions that are more common in society. But recently, Indian actors have become household names through popular films such as “Bend it Like Beckham” and “Slumdog Millionaire.” This fame has brought India, and its major religion, out of the background and into the spotlight.

With its renewed fame, I have been given an opportunity as a Hindu American to share the teachings of Hinduism with others and to clear up misunderstandings of the religion. It is so important to maintain my identity as a Hindu American, because I am a part of the generation that is starting to make major decisions about the future of our country. It would be a shame to watch the identity that my parents and so many others worked so hard to foster, halfway across the world from their motherland, disappear.

purnita howlader, 27, is of Bangladeshi descent. She was born in Urbana, Illinois, and lived in Minnesota, Italy and England before spending the majority of her childhood in Woodbury, Minnesota. She received a Bachelor’s Degree in Business in 2003 from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis/St.Paul, then spent five years working in the field of Human Resources. Purnita is currently attending law school at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. E-mail: purnita.howlader@gmail.com

Land of the Free, Home of the Veda: The Hindu American Identity & Cultural Synthesis

By Shivi Chandra

A nonresident indian who considers herself a hindu American will hear a variety of reactions over the course of her life, mostly relating to how nice it is that she chooses to “stay in touch with her heritage,” “remember her culture,” “take pride in her roots” and other such platitudes. As a result, the majority of nonresident Indians believe that their role as Hindu Americans is mainly a preservative one, and if they manage to emulate exactly the social mores of homeland Indian Hinduism, they have succeeded in their task.

I believe that the importance of being Hindu American is a great deal more than simply preservation. As citizens of a dual heritage, molded as much by Christmas as by Diwali, we would not do our identity justice if we did not add something original of our own to the state of flux that is the Hindu cultural canon. I believe that Hindu Americans have something of this sort–something extraordinary, something formed by our unique experience–to contribute to the world at large, and this is why my Hindu American identity is important to me.

This extraordinary thing is that being Hindu American represents access to both the secular and the religious facets of man’s most ancient attempt to make sense of the world. In the Hindu religious tradition, this is clearly visible in the Vedas, largely discursive texts which use dialectic, reasoning, mathematics and advanced science to find order in the bewildering metaphysical tapestry of the universe. For ancient Hindu scholars such as Shankaracharya, the implications of this took form in a religious impulse to strive for the highest, the greatest, the most excellent form of man possible to our conception, and the rest of Hindu religious thought has slowly woven a cocoon of rituals, social structures and sectarian belief systems around this central impulse. But the core of the philosophy always remained the same: that man is a great and powerful being, that because of the Godstuff of which his soul is fashioned he may triumph in any situation, that there is a purpose to life and that it is a beautiful and meaningful purpose.

In secular life, I believe this philosophical premise has found a true home in the United States of America. Here, the quest for egalitarianism, justice and opportunity for excellence in human life is honored more than in any place on Earth, and to experience the ancient Hindu philosophy of vasudhaiva kutumbakam, “the world as one family,” I need look no further than my own neighborhood, to the faces of the many immigrants who have found a home in American society.

Both Hindu philosophy and American secular wisdom speak to the core of man, and therefore I have always felt that these belief systems are uniquely compatible. The only difference is that the American philosophical tradition points to the Declaration of Independence and the Bill of Rights; the Hindu tradition to the Gita and the Rig Veda, but the theme of each is one: the triumph of the human spirit. One says it in a religious way, with rituals, poetry and faith, and the other with proofs, justifications and extensions that are far removed from their origins in the Judeo-Christian social ethos. This, to me, is the importance of being Hindu American: recognizing that I am in a position to reconcile faith and intellect, spirituality and science, passion and reason, as the two streams of my heritage have the capacity to do and have been doing for years.

Without realizing that the purest impulse of religion and the purest impulse of secular life is the same, I believe that society everywhere stands at the brink of emotional collapse. Creating a rigid line between religion and the rest of life has proved insanely impractical in the modern world. Regimes which consider themselves purely religious have turned into totalitarian empires of penury and subjugation, whereas self-proclaimed secular nations suffer an emptiness of the spirit derived from a contemplative vacuum, emotional isolation, and lack of spiritual dialogue. Religious and secular groups everywhere in the world have difficulty understanding and working with one another in any truly effective way, even though their mission is largely the same. If religion and secularism could be reconciled, these problems could be easily averted. And this is the benefit society will reap from Hindu American advocacy.

Hindu Americans must advocate for their heritage because our religion stands at a unique juncture between pure religion and pure secularism. The ancient rishis, after all, were experts at reconciling the secular and the religious. Aryabhatta was a philosopher, but also a mathematician. Ved-Vyas and Narada were wandering ascetics, but also superlative politicians. Dronacharya was a spiritual teacher, but also a weapons master. All of these people knew that the material and the spiritual are welded together in the ultimate productive life, and so they strove for excellence in all fields. They were ideal Hindus–but they would also not have been out of place among Jefferson or Hancock. The great men of both traditions taught a truly holistic, integrated lifestyle. And the greatest form of advocacy a Hindu American can perform is to live such a lifestyle herself–a life in which religion and secularism are not mutually exclusive, but form a synergy that is truly the hallmark of the purusharthi, the Hindu concept of the ideal man. If we can recognize and expound upon the astonishing similarities between Hinduness and Americanness, which people normally insist on compartmentalizing into religion and secularism, we will succeed in bridging an ancient and actually meaningless divide between East and West. This is a benefit not only for American society, but for all of mankind.

For me, this is truly the greatest advocacy possible: synthesis, not simply tolerance. I will learn and explore my binary heritage, synthesize its elements of rationality and excellence, and create an informed definition of what my religion and my culture mean to me. I will go out and live the life it mandates, show the world what a purusharthi looks like, and when I am asked how I was able to do it, I will say it was because I am a Hindu American.

shivi chandra, 20, was born in India, grew up in Michigan and is now an undergraduate studying international relations at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. She hopes to pursue a career as a sociological field researcher, and her research interests include trends in contemporary Indian culture and philosophy. She is particularly interested in the applications of Vedanta in the nonprofit sector. E-mail: schand11@jhu.edu