By Nancy Levine

Access to Humla, the farthest northwestern district in Nepal, depends on very elemental factors. The flight path follows the narrow winding passage of the deep Karnali River Gorge as it cuts between the major mountain chains. Just as the nomadic traders have passed through the pine forests and alpine valleys for centuries, their paths dictated by changes in the weather, a flight through the rugged peaks depends on the breaking of the clouds and the placation of the skies.

My destination was Nyinba, a group of villages scattered across the south-facing valleys on the spur of the Takh Himal, a mountain chain bordering Tibet. The plateau serves as a cultural crossroads for Humla’s mix of ethnic groups, an ancient resting point where migratory peoples from India, Tibet and Nepal have settled to take advantage of the trade routes that run through the mountains. The Tibetan-speaking peoples known as Bhotias inhabit the Northeast, while the Nepali-speaking Hindus who migrated from India prefer the fertile valleys and river beds.

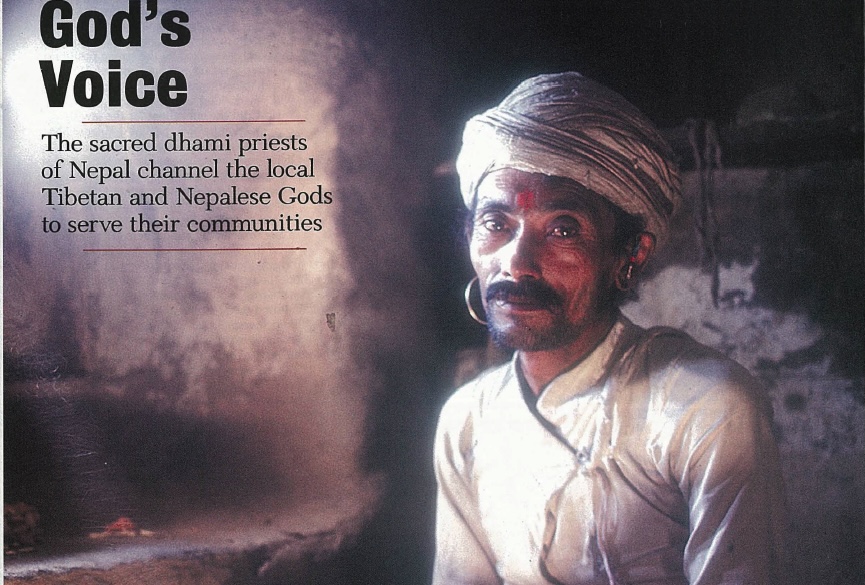

The place is filled with shrines to Gods and spirits who are thought to infuse the land, water and sky. The Gods control the harvest; they offer protection with one hand while destroying with the other. For the people here, communication with the Gods is a vital part of everyday life. These supernatural beings manifest themselves through the human oracle, the village dhami. With this man as a medium, the people of Humla are able to communicate both with benevolent and malevolent spirits.

As we walked single file along the narrow trail, I was told of the death of the great dangri Kandro. The dangris are the men who recite the prayers that induce the God to come into the dhamis. Kandro had been my friend and mentor, describing to me the intricacies of oracular spirit-possession, including a sacred chant, known only to the dangri priests. Central to the chant was the invocation to the villages’ protective Deities, who are summoned from the heavens, from far-flung corners of the earth and from the underworld to partake of the offerings prepared by the assembly of worshipers. On arrival, the God will enter into the body of the dhami. The dangri aids the union between the people and the Gods with chants, and translates the garbled prophecies that the dhami makes when under the God’s influence. Kandro’s death meant that his son, Tshering, would inherit the office of dangri and continue the family tradition.

However, Tshering was reluctant to take on his inherited role; he considered himself a modern man and found the traditional folk practice of magic and herbal remedies of little merit. He was also a dedicated follower of canonical Tibetan Buddhism, which frowns upon many of the practices of village worship. Faced with the unwanted inheritance, he announced to the community that he would allow the family tradition to lapse. Privately he spoke of his skepticism, believing the dhamis shammed possession and that it was impossible for Gods to come to men in this way.

The villagers were enormously upset by Tshering’s refusal. Not only had they lost their finest dangri, but they also had a major problem of succession to resolve. Local leaders approached Tshering to ask him when he intended to travel to Tibet to cast his father’s remains into the sacred waters of Lake Manasorovar and be installed as dangri himself. But again he refused.

At the next collective possession, the oracle related a series of dire events about to befall Tshering’s family if he did not take up his dangri role. Silver coins associated with dhamis and sacred pledges began to appear around his home. Because Tshering had political ambitions and wanted to maintain the good will of the people, he finallyresolved to journey to Tibet with his father’s remains.

That summer Tshering traveled to Lake Manasorovar, alongside fellow initiates, and cast into the waters the tsha tsha, bas-relief figurines made from the ashes of the deceased mixed with clay. The sons of the deceased dhamis must bring their fathers’ long coil of hair, cut off just before the moment of death. It is the dhami’s matted coil of hair, bound with filaments donated by worshippers, that serves as the conduit for the God.

The dhami initiates must plunge beneath the surface of the waters and enter into a trance to attract Divinity. To plunge into an icy, high-altitude lake is risky at the best of times, but for the dhamis the danger lies not in the temperature of the water but in the disposition of their Gods. If the new dhami has erred from duty, the spirits will lead him halfway to the palace and then abandon him in deep waters. The immersion gives the initiate the power to voice the words of the Gods and to deliver divine prophecies.

The reluctant dangri Tshering was deeply moved by the installation ceremony and returned to Nyinba determined to follow his new calling. The same cannot be said about another skeptic, Angyal, who was

eventually released from his obligation because he had an affair with another man’s wife. As a dangri heir, his misdemeanor was a grievous insult to the Tibetan God his family served.

The dhamis are central to Nyinba ceremonial life, and their spirit-possession is the high point of every collective ritual. The spirit possession ceremonies all follow a similar pattern. Initial offerings are prepared and an altar set up. This is followed by the invocation, which describes the journey of the Gods from the heavens to the glaciers, onto the hillsides, through the lakes and forests, and finally to the place of worship.

When the Gods arrive, the dhami will begin to yawn and tremble, gently at first, and then more violently. When possession takes hold, he will begin his trance dance before the assembly. During the dance, the dhami will perform extraordinary feats. Some swallow ladles of boiling oil and then spit the scalding liquid onto their captive audience; others insert red-hot implements from the fire into their mouths. Some dhamis drink vast quantities of water, which is said to cause rain the following day. Iron swords and rods might be bent, while others scoop up handfuls of grain that appear to sprout when the prophecy is made. These feats which seem quite genuine and reveal the dhami’s extraordinary strength in possession and his imperviousness to physical pain are taken as proof of the dhami’s power; though it must be said that there is often ample opportunity for sleight of hand.

The dangri’s role is to invoke the local protective Deities who enter into and occupy the body of the dhami. The dangris then approach the Gods, now given human form in the body of the village dhami, to request a bountiful harvest, divine guidance on the phasing of the agricultural year, and the scheduling and safety of the annual trade journeys.

New dhamis are expected to perform a characteristic miracle as an indication of their authenticity. They are judged not only on these displays but also on the accuracy of their predictions.

Among ethnic Tibetans, it is the lamas that voice many of the criticisms against dhamis and dangris. They find the dhamis’ claim to be incarnates of the highest-ranking Tibetan Gods as preposterous, for their Deities take no part in human affairs. The lamas find the dangri chant to be an impoverished version of Tibetan Buddhist practice interwoven with pre-Buddhist practice and believe the display of special powers a sham. The dangris and dhamis on the other hand, acknowledge the superiority of orthodox Tibetan Buddhist practice without finding it invalidating of their own practice.

Another problem threatening the dhamis is that the Gods who possess the dhamis demand the sacrifice of animals at the time of possession. The sacrifice of animals is abhorred by the Tibetan Buddhists. The people of Nyinba recoil from killing animals for food, and they regularly assign the task to Nepali servants.

Despite the controversy, the oracles provide a bridge between neighboring ethnic groups, allowing for the most popular form of inter-ethnic interaction in the region. This fascinating intermingling of religions is further evidenced with the fact that while Tibetans perceive Gods such as Gura as being of Nepali derivation, Nepalis identify these very Gods as having Tibetan origins!

Among the fervent devotees of these Gods are the poor and the powerless of the various ethnic groups. It is they who seek out the Gods in public and private consultation and request protection against injustice and the wrongs done to them. This is the only path to justice that these people have, as formal court proceedings are both costly and seldom impartial. The local leaders are notorious for taking advantage of those less powerful than themselves. The Gods, by contrast, are impartial and incorruptible. Further, people from any background will be given a fair hearing by the dhami, who serves everyone, rich or poor, high status or low.