BY ANIL MEHROTRA

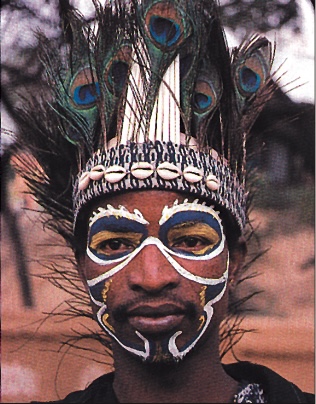

As the red sun sets and a silken darkness creeps in, twelve dark-skinned men with Negroid features and painted faces perform the “Jungle Dance ” by the light of flickering torch fires in Zanzibar, Africa. Passing tourists might not consider this scene unusual, but it is. These performers don’t just live down the street. They are Sidhi tribesmen from India who are of African descent, performing in their ancient homeland while on a world tour to honor and preserve their cultural heritage. Although their music and dance is authentic and their love of their legacy is true, they will admit that–although they respect this land of their ancestors–they are quite happy to be living in India.

As the evening stretches into night and the pounding drums cast a mesmerizing spell over the crowd, the aged among the audience become more and more attentive, straining their ears and narrowing their eyes as they attempt to recall strains of music they have almost forgotten. They have not seen or heard anything like the performance they are now witnessing since before their grandparents died. Yet, they feel it through their nerve system as if their ancestors were pounding the dust and drums themselves.

As the performance continues, the trancelike rhythms gradually charge the atmosphere with electrifying power. The crowd sways. The music intensifies. Finally, one dancer throws a freshly plucked, husked coconut high into the black cavernous sky. The crowd looks up. The coconut comes down, smashing on the head of one of the dancers with a thud, splitting and spraying the stage and the audience with its milk. The crowd is thrilled with this ecstatic climax. The show is over.

The Sidhis are a diffused community of people who came from Africa but now live throughout Southeast Asia. In India, about 30,000 Sidhis make their home in and around Junagadh, Gujarat.

These Africans first arrived in India during the twelfth century, mainly as soldiers, sailors and merchants. Some were warrior-slaves to Indian kings who valued them for their loyalty and fighting spirit.

Through the generations that followed, the Sidhis that remained in India adapted to the lifestyle , yet retained some ancient cultural practices and a few syncretic forms of worship. Today, their only link with Africa is through their music, dance and the few customs they have maintained. They speak no African languages and do not know the specific origin of their ancestors.

Sidhis of India are dedicated to a Muslim Sufi saint named “Sidi Mubarak Nobi, ” who saint studied Sufism in Iraq but lived in India. Also a businessman who dealt in the sale of agates, he first visited Gujarat seeking these semiprecious stones for clients in Africa and the Middle East. Eventually he became famous for his power to heal the sick and settle disputes, and the Sidhis of India flocked to him. When he died, his body was entombed at Junagadh in Gujarat, which thereafter became an important pilgrimage destination for Indian Sidhis.

The Sidhis’ stage performance consists of dancing and drumming. Eight performers dance while four play drums called mugarman and musical drone boxes called malunga. Their featured dance, called the zikr, is a riveting amalgamation of agility, strength and speed, characterized by a feverish, climatic ending.

“The general population in India thinks we are Africans, ” says Yunus, a Sidhi from Jambur who speaks fluent Gujarati, but no Swahili. “We are Indians. Swahili is the language of our forefathers, and we should not forget it. Though we do use it in some of our songs, we do not know its true meaning. We enjoy going to Africa to perform the jungle dances, but we would never want to settle down there permanently.”