BY MARK HAWTHORNE

When she awoke from a heart and double-lung transplant operation at Yale-New Haven Hospital in Connecticut in 1988, Claire Sylvia was not only happy to be alive–the 48-year-old dancer craved beer, green peppers and fried chicken, foods she had given little thought to prior to the transplant. It quickly became apparent to Claire that she had developed more than just a fondness for new flavors. She had also acquired some intriguing personality traits, including an increased libido. In fact, she had the desires and boundless energy more suited to an 18-year-old male than a woman approaching middle age. By age 50, she was backpacking around Europe, searching for she knew not what.

Claire’s story, chronicled in her 1996 memoir, A Change of Heart, gets even stranger when she begins having dreams in which she communicates with a young man whose initials are T. L. She feels certain that “T. L.” had donated the heart now beating in her chest and the lungs she now breathed with. In keeping with official policy, however, the staff at Yale-New Haven Hospital had told Claire nothing about her organ donor, except that he died in a motorcycle accident in Maine. But as time goes by, and the intensity of Claire’s dreams increases, she begins to put clues together and discovers that the donor was an 18-year-old man named Tim Lasalle. She soon sets up a meeting with Tim’s parents, accompanied by a friend and Jungian psychoanalyst named Robert Bosnak. Claire learns from Tim’s family that he had loved green peppers, beer, and especially chicken nuggets.

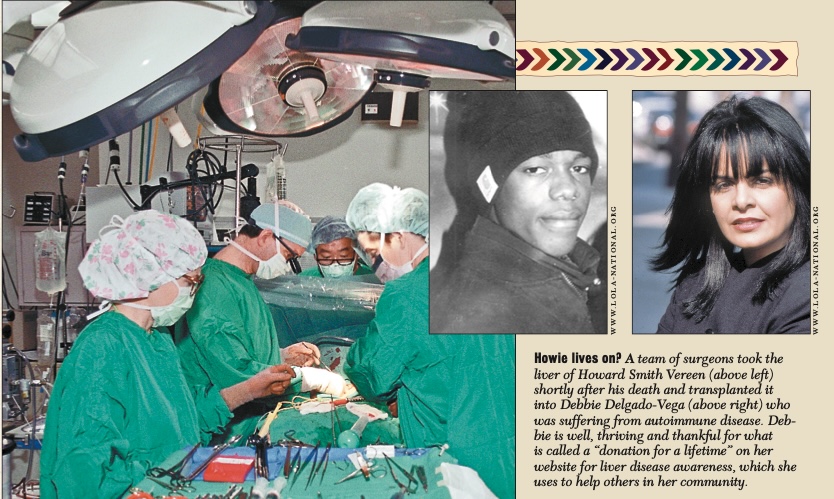

Skeptics will naturally label these happenings a coincidence, but Claire’s experiences are not unique. In 2003 the Discovery Health Channel explored this issue in Transplanting Memories. Among those featured in the documentary is an eight-year-old girl who receives the heart of a murdered 10-year-old girl; her ensueing nightmares, in which the heart recipient sees the killer, help solve the crime. Viewers also meet Debbie Vega, who received the liver of an 18-year-old named Howie. Howie loved peanut M&Ms, cheese doodles and karate, and he seems to have passed all these characteristics on to Debbie.

Looking for Scientific Answers

Yet, medical science is reluctant to admit that such post-transplant experiences occur. In the face of overwhelming anecdotal evidence, most doctors offer scientific explanations for these phenomena. Writing on TransWeb.org, an organ transplant Web site, transplant surgeon Jeff Punch, MD, states, “A transplant is a profound experience, and the human mind is very suggestible. Medically speaking, there is no evidence that these reports are anything more than fantasy.”

Among the theories explaining how such experiences could occur, “cellular memory ” is one of the most popular. The term has come to refer to the capacity of living tissue cells to memorize and recall characteristics of the body from which they originated. While many in the scientific community remain skeptical, Paul Pearsall, PhD., is convinced that the heart has its own form of intelligence. Cells have memory and communicate beyond time and space.

He believes the heart processes information about the body and the outside world through an “info-energetic code ” a complicated network of cells and blood vessels that serves both as our circulatory system and as a structure for gathering and distributing energy information. Furthermore, he contends that the soul, at least in part, is a set of cellular memories that is carried largely by our hearts. This view is, of course, closely aligned with ayurveda, which regards the heart as not merely a pump but also the seat of consciousness itself.

And then there’s Dr. Candace Pert, a pharmacologist and professor at Georgetown University who believes the mind resides throughout the body, not just in the brain. Dr. Pert is well known for her work with neuropeptides the molecular language that allows the mind, body, and emotions to communicate. She writes in The Wisdom of the Receptors: Neuropeptides, the Emotions, and BodyMind (1986), “The more we know about neuropeptides, the harder it is to think in the traditional terms of a mind and a body. It makes more and more sense to speak of a single integrated entity, a body-mind.”

Still, most Western doctors consider cellular memory the stuff of science fiction. Indeed, the idea of a body part carrying “memories ” to another body is the basis of the 1920 sci-fi novel Les Mains d’Orlac ( “The Hands of Orlac “) by Maurice Renard. It is the tale of a celebrated pianist who loses his hands in a train wreck and is given the hands of a murderer in a transplant operation. He then assumes the personality of his appendages’ psychopathic donor. Renard based his fictional surgeon on Dr. Alexis Carrel (1873-1944), a French biologist and surgeon whose experiments with transplants and grafting procedures earned him the Nobel Prize in 1912.

Exploring Alternative Causes

Claire Sylvia’s case reminded biologist and author Rupert Sheldrake more of reincarnation than cellular memory. Known for keeping an open mind where unconventional science is concerned, Dr. Sheldrake believes the tastes and traits Claire “inherited ” from Tim can be attributed to the morphic field in and around the organs. Asked to elaborate on his theory, he responded: “I think that transplanted organs may help to tune the person into the morphic fields of the person they are transplanted from. If somebody had several different transplanted organs from different people, then there might be several different influences working upon them. On the other hand, it may be that some organs have more influence in this respect. The heart may lead to more transfer of memories than, say, a kidney.”

Some experts theorize that transplanted organs may retain some form of electrical energy. To explore this theory, cardiothoracic surgeon Mehmet Oz, MD invited energy healer Julie Motz to participate in a heart transplant procedure. As director of the mechanical heart-pump program at the Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York, Dr. Oz combines Western medical technology with Eastern tools and alternative therapies, such as acupuncture and aromatherapy. When Motz put her hands on the ice chest containing the donor heart, she had a vision of two women in a car, arguing. When Motz told Dr. Oz what she’d seen, he explained that the heart was from a woman killed in an automobile crash; she and her mother had been quarrelling in the car. Later, when the heart was inside the recipient but wouldn’t start beating, Motz suspected that negative energy from the fatal argument had made the heart “afraid ” to beat. As Motz explains in Transplanting Memories, “I leaned over and whispered in [the recipient’s] ear. I said, ‘You have got to get angry, and you have got to give your new heart permission to get angry.’ And then I did something that I don’t usually do because it looks a little weird. I actually put my hand over the surgical drape and sent energy directly into the heart. And the heart came back and started to beat. The perfusionist [who operates the heart-lung machine during surgery] told me later he’d never seen a heart come back so far, so fast.”

While many mainstream scientists dismiss this issue as fantasy, alternative healers continue to explore the causes of transplanted memories. Asked about Claire’s experiences, her friend Robert Bosnak said, “Assuming that her spirit merged with Tim’s, I have no explanations, just musings. I could imagine that the body is like a hologram in which each shard is a full but vague picture of the whole. The greater the mass of genetic material, the more precise the picture becomes. I had predicted that, based on Claire’s post-transplant behavior, Tim would have been hyperactive, which was indeed the case.” Claire Sylvia continues to do well, and she now rarely experiences the strange feelings and cravings she inherited from Tim. “All has lessened as time goes by, ” she emailed recently. “I am more fully integrated now as ‘third being.’

HINDUISM’S VIEW OF ORGAN TRANSPLANTS

Hindus believe every action has karmic implications and something as serious as replacing a major organ can carry some of the donor’s karma to the recipient, as demonstrated when a recipient has acquired some of the donor’s characteristics. Hindus also believe that the soul of the donor lives on in the inner world after death, and may influence the organ recipient, an explanation carefully avoided by science. The fact that part of a deceased donor’s physical body still “lives ” may interfere with his moving on to the next incarnation. Earthbound, kept in close proximity on the astral plane to the recipient by virtue of his still-living organ, the donor expresses his desires, felt as impulses and thought forms by the recipient. These could fade if the donor finally does move on, but some traits may have already been integrated into the recipient’s personality as vasanas (mental patterns) of her own.

In 1999, Hinduism Today consulted a number of prominent swamis and Hindu physicians on the subject of medical ethics. Regarding organ transplants, Swami Satchidananda of the Integral Yoga Institute was unequivocal. “What are we doing by transplanting organs?” he said. “By replacing organs in a clearly dying body, we are not allowing the soul to fulfill its karma in this life by dying at the proper time and getting a new body. The trend of science seems to want to keep the soul indefinitely in the same old body with repaired parts. This is not the correct thing to do.” Swami Tejomayananda of Chinmaya Mission agreed. “The Hindu way of life is to accept the inevitable, ” he said, “to go through the karma, exhaust it, and be free to take on new life to evolve further spiritually.”

But Swami Chidananda Saraswati Maharaj ( “Muniji “) of Parmath Niketan, Rishikesh, felt that it is “important to donate organs ” in the Hindu spirit of giving and sacrifice. Swami Bua of New York also supported organ transplants. “Let us encourage and support the scientists and medical men who are working with pure intentions towards a painless, diseaseless society, ” he said. “We should only guard against unscrupulous traders in human organs.”

Dr. Virendra Sodhi, a experienced ayurvedic and naturopathic doctor in Bellevue, Washington, advocated a compromise. “Some transplants, such as the cornea, are okay, but not the heart, which is the seat of the soul according to ayurveda, ” he said. “If the quality of life is going to be very good after the transplant, I might not have a problem, but if they have to be on harsh drugs all the time, maybe transplanting is not the best idea.”