By Vrindavanam S. Gopalakrishnan, Karnataka, India

The express train carrying us chugged into the Udupi station in the January dawn as the golden rays of the sun pierced through the thin fog enveloping the area. This old town in the southern Indian state of Karnataka is famed as the birthplace of Sri Madhvacharya, founder of the dvaita vedanta philosophy some seven centuries ago. Though his personal Deity was Hanuman, he established a temple for Lord Krishna in an ancient matha on the banks of a large pond, next to two ancient Siva temples–Chandramaulesvara and Ananteshvara. So famous is his temple now that when the name Udupi is heard, the people of South India immediately pray, “Udupi Sri Krishna” in reverence.

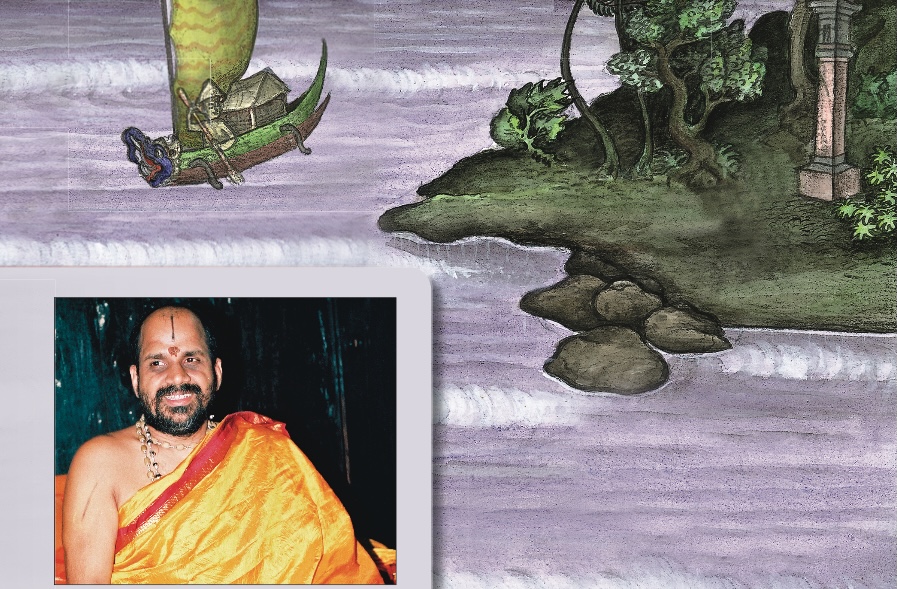

I was here for Paryayam, the biannual religious function to hand over the responsibilities of managing the Krishna temple and performing the daily pujas. These responsibilities rotate among the heads of the Ashta Mathas (literally, “eight monasteries”) which were founded by Madhvacharya in the 12th century. This year commences the third term of Sri Swami Sugunendra Tirtha, head of Puthige Matha (www.puthigeshree.org/ [www.puthigeshree.org/]), as he takes over from Sri Swami Vidhyasagara Tirtha of Krishnapura Matha.

Coinciding as it does with the festival of Makara Sankranti, Paryayam is normally celebrated with great pomp and attended by tens of thousands. But this year’s festival was overshadowed by bitter controversy. The orthodox Madhvacharya community had been embroiled in dissension since 2005, when Sri Sugunendra Tirtha traveled to the Middle East, Europe, Japan and America–thus committing the sin of samudrayana, “crossing the ocean.” After much highly public debate and legal action, a compromise had finally been reached: Sri Sugunendra Tirtha would take over the responsibility for the worship, but would personally perform only six of the required sixteen daily pujas–those six which do not require touching the Deity. For the time being, the heads of the Shirur and Kaniyur Mathas would conduct the other ten daily pujas, known as Mahapujas.

Although an agreement had been reached, the controversy left its mark: this year’s Paryayam festival was completely boycotted by the heads of the other seven mathas. Sri Sugunendra Tirtha’s supporters, however, were determined to make the best of the situation. As I entered Car Street on the morning of January 17, I found hundreds of young men engaged in decorating the street for the procession–which passes in front of all three temples, the shops, the monastery buildings and even the side lanes–with hundreds of kilos of flowers. Devotees poured in from faraway villages, and by midnight of January 17-18, an estimated 80,000 were present to witness the Paryayam in the early hours of the 18th. It was a drop in attendance from previous years, but still a massive crowd.

Parayam normally begins with a huge procession carrying the head monks of the eight mathas in palanquins from a point four kilometers away. This year, all the palanquins were empty save that of Sri Sugunendra Tirtha. Subhadra, the Sri Krishna temple’s beloved elephant led the parade, majestically caparisoned, moving joyously as if dancing to the tune of the instruments. Traditional music accompanied by different types of percussion instruments filled the air along the narrow road leading to Car Street. Huge tableaux depicting the life of Lord Krishna and Madhvacharya were carried in illuminated vehicles through the narrow lanes. Then followed the palanquin carrying the Paryayam Swami, Sri Sugunendra Tirtha.

The procession arrived at Puthige Matha, of which Sri Sugunendra Tirtha is the head. A heavy police presence and the use of a metal detector at the door attested to the apprehension felt by town officials, but nothing untoward occurred. Following tradition, a white cloth was unrolled from Puthige Matha monastery all the way to the Sri Krishna temple, where the ceremony to place Sri Sugunendra Tirtha upon the Sarvanja Peetha was to begin. Literally, “seat of universal spiritual knowledge,” the Sarvanja Peetha was first occupied by Madhvacharya himself. Whoever occupies the seat administers the affairs of the temple and conducts the sixteen daily pujas. But this year there was nothing normal about the transfer of responsibility.

Under normal circumstances, Sri Sugunendra Tirtha would have been led in procession from Puthige Matha to the Krishna temple by the heads of other seven mathas. Since they boycotted the event, he was forced to enlist the help of Sri Reghumanya Tirtha Swami, head of Bheemanagatta Matha, an upamatha, or subsidiary monastery. Arriving at the Krishna temple, they had darshan of Lord Krishna through the kanakanakindi, a golden window (see photo page 24), through which one can see into the inner sanctum. Sri Sugunendra then proceeded across Car Street to the Ananteshvara and Chandramaulesvara temples to pay obeisance to Lord Siva.

At this point, the outgoing monk, Sri Vidhyasagara Tirtha of Krishnapura Matha, would ordinarily have brought Sri Sugunendra Tirtha to the Sarvanja Peetham. Sri Reghumanya acted in his place, handing over the temple keys and the revered akshaya pathra, literally, “inexhaustible vessel.” The original akshaya pathra appears in the Mahabharata where it was a cooking pot given to Draupadi by the Sun God. It gave an unlimited amount of food each day until Draupadi herself had finished eating. Here, only a ladle of the same name is handed over to the incoming swami, but the idea is identical–to provide unlimited food to Lord Krishna’ devotees. With this ritual, the management of the temple is officially assumed by the incoming swami.

In the final rite of installation, the new Paryaya Swami applies sandal paste in blessing to the foreheads of the other seven monastery heads–a time-honored event that became one more casualty of this year’s strife.

With the ad hoc installation concluded, the remainder of the day’s celebrations proceeded normally. Sri Sugunendra Tirtha and large numbers of devotees moved into the Rajangana Durbar, an attached convention hall, where numerous dignitaries, including politicians and social leaders, were present to receive him.

One of the important aspects of this public address is the appointment of the Diwan, or chief administrator, as well as various other posts. Most of these were given to people connected with Puthige Matha. The position of Diwan is coveted and lucrative, as it oversees the entire administration and finances of both the Putige Matha and the Sri Krishna Temple. Sri Sugunendra Tirtha appointed not one, but two Diwans, both his own brothers. This bit of nepotism is instructive with regard to the question of orthodoxy. In other conservative monastic orders of India, swamis renounce their birth families and avoid contact with them but will not hesitate to travel overseas. Here at Udupi, some swamis even employ their relatives in their monasteries, yet, ironically, they hold to not “crossing the ocean.”

It was not until the day of Paryayam that the heads of Shirur and Kaniyur Matha agreed to assist with the daily pujas, thus ameliorating the controversy. It is a normal practice for the heads of other monasteries to help with the intense ritual schedule, but this year none volunteered until the last minute.

This awkward transition in leadership for the Krishna Temple was only the latest round in a heated debate that has gone on since Sri Sugunendra Tirtha returned from Europe and America in 2005. Efforts were made to prevent him from assuming the post at all; but neither the government nor the courts would interfere, and the efforts came to naught.

It was not the first time the Ashta Mathas have been rocked by the same controversy. Sri Vishvavijaya Tirtha Swami, the designated successor to the head of Pejawar Matha, had to relinquish his post for going to the United States in 1987. He went with the blessings of his guru, Sri Vishvesha Tirtha, but refused to undergo the purification rites requested by the Madhva establishment upon his return (see www.hinduismtoday.com/archives/1988/02/1988-02-05.shtml [www.hinduismtoday.com/archives/1988/02/1988-02-05.shtml]). Sri Vibhudesha Tirtha Swami of the Admar Matha suffered the same fate for a similar offense, and had to install his chief disciple, Sri Vishwapriya Tirtha Swamji, as the Paryaya Swami in his stead.

Sri Sugunendra Tirtha, who is an international president of the World Council of Religions for Peace, said that he only went abroad to propagate Hindu Dharma and dvaita principles and not for his personal purposes. He told Hinduism Today, “When good things are done, there are people to oppose it. Lord Krishna is the final judge. Mere economic globalization is not enough; it is necessary for there also to be spiritual globalization.”

Crossing the ocean–

an evolving issue

Controversy over samudrayana, “ocean voyage,” is nothing new in recent Hindu history. Swami Vivekananda was, because of his international travel, denied entry to the temple where his guru Sri Ramakrishna served for 40 years (see sidebar page 25). The priests who serve the main Deity of Tirupati temple will not leave India. On the other hand, this same temple’s training school has supplied priests for many temples in other countries. The Dikshitars of Chidambaram, a staunchly conservative community, allow for travel, but require purification upon return.

Hinduism is not the only religion that restricts travel; Jain monks and nuns are required to walk everywhere, and barefoot at that. However, Acharya Sushil Kumar Muni, a prominent Jain monk who passed away on in 1994, traveled widely by plane in his later years. In 2005, Jain monk Aacharya Rupachandgi visited the US. A news report at the time said, “Until recently, Rupachandgi would not have been allowed to travel anywhere his feet wouldn’t take him. But the growing population of Jains in the United States has caused some rules to be relaxed, so that teachers from India can nurture Jain practice in this country.” Hinduism is undergoing a similar adaptation. While some priests and swamis will not cross the ocean, many others will, even from otherwise conservative traditions.

The prohibition is clearly stated in several scriptures. The Baudhayana Sutra, one of the Hindu Dharma Shastras, says that “making voyages by sea” (II.1.2.2) is an offense which will cause pataniya, loss of caste. It offers a rather difficult penance: “They shall eat every fourth mealtime a little food, bathe at the time of the three libations (morning, noon and evening), passing the day standing and the night sitting. After the lapse of three years, they throw off their guilt.”

The difference of practice on the issue among the various Hindu denominations is based on the scriptures each considers authoritative. Harsha Ramamurthy in his erudite article on the issue (kamakshi16.tripod.com/samudrayana.html [kamakshi16.tripod.com/samudrayana.html]), explains that, according to Baudhayana Sutra, the highest authority in deciding a question of dharma is shruti, our primary scriptures, the Vedas and Agamas. Next is the smriti, the secondary scriptures, which include the Dharma Shastras. Third is sampradaya, the teachings and practices of a specific lineage. He concludes, “Though there seems to be no direct ban on ocean travel in shruti, because of the bans in smriti and sampradaya, such travel is considered a banned activity.” He said in communication with Hinduism Today that the ban is observed both by the Madhva Sampradaya and Smarta Sampradaya (which includes the Shankaracharyas of Sringeri, Kanchi, etc.), as both adhere closely to the Dharma Shastras. He added that the ban applies to all three upper castes, and not just brahmins. It also applies to sannyasins, who–in his tradition–can only be from the brahmin caste. He pointed out that other Vaishnava Sampradayas, such as the Srivaishnavas, who follow the Pancharatra Agama, travel freely. He gave the example of Chinna Jeeyar (www.chinnajeeyar.org/ [www.chinnajeeyar.org/]), a follower of Visishtadvaita, who travels extensively. Similarly, the swamis of the Vaishnava Swaminarayana sect travel extensively.

Why the ban?

In the Baudhayana Sutra, the ban is discussed in the context of a description of the geographical limits of India which concludes that within its boundary “spiritual preeminence is found.” Generally, two reasons are given by scholars for the ban. The first is that it is impossible to maintain one’s required daily religious observances on a ship, particularly thrice-daily personal worship. The second is that one will incur the sin of mleccha samparka, usually politely translated as mixing with foreigners. Mleccha, however, is more accurately translated as “barbarian” or “savage.” One should remember that triangle-shaped India is surrounded on two sides by ocean and the third by the Himalayas. Leaving ancient India to unknown lands meant either ocean travel or journey by foot through rugged terrain. It is a logical conclusion that travel outside India in those days did make religious observance difficult and took one into cultures that were not Hindu. The question is whether such concerns apply today; and if they do not, how the decision to adapt the scriptural dictate should proceed.

Speaking to Hinduism Today, Sri Vishweswara Tirtha–the head of Pejawar Matha and the senior monk of the Udupi Ashta Mathas–said that violation of the scriptures cannot be accepted. “Sri Sugunendra Tirtha had crossed the ocean and, therefore, strictly following the scriptures, he could not perform the Mahapuja of the Lord Krishna by touching the Deity. We have reached a consensus that he can occupy the Sarvanja Peetha at the current Paryayam rituals, but not touch the Deity.” On January 18, 2008, a convocation of 500 priests, scholars and Madhva swamis (including six of the eight Ashta Mathas), supported this opinion and concluded that the ban on travel should not be changed, according to Dr. Suresh Acharya, an Udupi-based scholar.

Other views on crossing the ocean

According to Acharya Narendra Bhushan, an eminent scholar on the Vedas and other ancient texts on Hinduism, there are no verses in the four Vedas prohibiting monks or priests from traveling abroad by crossing the ocean. Instead, he pointed out, there are verses emphasizing the need for building ships and travel.

He spoke with Hinduism Today at his Vedic Mission office close to the Chengannur Mahadevar Temple in the Allappuzha district of Kerala. He said Rig Veda 1.8.9.1 clearly describes ship building. It specifically mentions that one should travel for the accomplishment of one’s responsibility to preach the dharma. He pointed out that several verses describe what appear to be vehicles that travel in the sky, perhaps anticipating our modern airplanes long ago.

In my home state of Kerala, we had the unusual case of Vishnu Narayan Namboothiri, a poet and former head priest of Sri Vallabha Temple in Thiruvalla. He was dismissed from his priest job for traveling overseas. However, he received an apology and was reinstated after a few months by the thantri (chief priest) who realized none of their authoritative scriptures prohibits priests from traveling abroad.

Hinduism Today consulted with priests in other parts of India for their view. Sri Muthu Vaduganathan, a priest associated with the Pillaiyarpati Gurukulam in Thevar District of Tamil Nadu, agreed that the tradition has been for priests and sannyasins to not move far away by crossing the ocean. But, he said, there are historical accounts of Hindu saints who crossed the ocean. “I am told,” he said, “that there is a penance to be performed when a sannyasin or priest crosses the ocean. The existence of this penance shows that as per the need and their own deeper vision, a sannyasin or priest can cross the ocean to preserve and make his mother religion flourish. But this should not be done for any materialistic need.”

Dr. A.V. Ramana Dikshitulu, head priest of the Balaji Temple in Tirumala, one of India’s most respected and popular pilgrimage destinations, said, “None of our priests who serve in the main sanctum can cross the ocean. Neither I nor any member of my family have done so, despite lucrative offers from abroad. Serving the Lord here is most important to us. The Balaji Temple is governed by the Vaikhanasa Agama. It says that the people outside India are akin to mlecchas, barbarians, who do not follow any rules or code of conduct, and therefore it forbids visiting such places. These places have habits, food, relationships and other things which could make us corrupt and impure.”

“According to the Agama, all brahmins are supposed to worship at sunrise, midday and sunset, called trikal gayatri sandhya,” he explained. “This trikal sandhya cannot be performed on a plane or ship; it must be done on the earth.” Dr. Ramana Dikshitulu does not specifically rule out “crossing” an ocean, for he himself flies occasionally from Chennai to Kolkata, a flight which goes out over the Bay of Bengal. But as that flight is only two hours long, he does not miss his trikal sandhya as he would on a longer flight or a voyage by ship, and he does not land outside India. He was unaware of any penance to offset crossing the ocean.

With regard to Udupi, he said the controversy was unfortunate. In his opinion, Sri Sugunendra Tirtha should have understood the consequences of his travel plans and either not traveled at all, or accepted the judgment of those who sought to abide by the scriptures of the Madhva Sampradaya after he did travel. The entire matter, he felt, should not have become such a public spectacle.

Dr. S.P. Sabharathnam Sivachariyar, South India’s foremost expert on the Saiva Agamas, said, “Rules related to the crossing of the ocean are laid down only in a few Dharma Sastras. Such rules are not to be found in the Vedas, Puranas, Saiva Agamas or Vaishnava Agamas. Yati Dharma Samucchaya, one of the most authentic texts dealing with the life system of the yati (mendicants and swamis), goes to the extent of saying that monks should be wandering throughout the world, even crossing the oceans. It says that to keep limited by the boundaries of one particular town or country is quite contrary to the high and noble visions of an enlightened yati.” Members of his priest caste, the Sivachariyars, freely travel abroad both for special functions and to serve as resident priests of temples in the West.

Conclusion

Clearly the Dharma Shastras’ ban on ocean travel was intended to maintain the religious strength and purity of the individual, and to prevent negative external influence from non-Hindu cultures. Other cultures had the same concern. One can note that the very word barbarian (used to translate mleccha with a strongly negative connotation), just meant “foreigner,” in the original Greek, yet came to describe an uncultured or brutish person.

Baudhayana Sutra makes the point more than once to delineate ancient India’s boundaries and declare it a sacred land out of which one should not step. But what have we today? In the east and west of what was ancient India we have Bangladesh and Pakistan, both Muslim-majority countries hostile to Hinduism. Modern India itself is a declared secular state. Its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, had little regard for religion and advocated sending priests out to work and turning all the temples into schools. And we have the Indian states of West Bengal, Kerala, Tripura and–from time to time–Tamil Nadu, all dominated by declared atheistic political parties.

Meanwhile, across the ocean–and leaving aside how priests got to the ancient Hindu civilizations of Southeast Asia and Indonesia–the modern diaspora has created significant Hindu populations in nearly every country of the world. The difficulties of living in the land of the mlecchas have indeed manifested, both for the original emigrants and their offspring. But thousands of Hindu communities worldwide have also struggled hard to maintain their religion through home worship, building temples and bringing priests and swamis to their country. It was Sri Sugunendra Tirtha’s defense that he had gone to the US to teach at the invitation of Hindus who follow Madhvacharya’s philosophy. It is also true that he knowingly broke the rules of his sampradaya, and then fought the logical consequences.

The swamis and priests who leave India do so to visit another community of Hindus, or are asked to come by non-Hindus sincerely interested in the Hindu wisdom. They have not gone out to consort with and be polluted by “barbarians.”

Hinduism prides itself in its ability to evolve and deal with new realities. Change is slow, as one after another of the hundreds of individual sampradayas faces an issue and makes a decision. Steadfast orthodox groups such as the Chidambaram Dikshitars, various Vaishnava denominations and many orders of swamis allow travel outside India. Hinduism Today has seen no compilation of how many traditions allow travel and how many do not, but it would appear that today an increasing number no longer follow the Dharma Shastras in this regard, focusing instead on meeting the basic religious needs Hindus living overseas. PIpi

A CHARIOT OF FIREWOOD FOR TWO YEARS OF COOKING

A unique feature of the Paryayam is the two-story firewood chariot, Kattige Ratha (at right). Requiring one year to build, it is a obligatory gift from the outgoing swami to the incoming one. By tradition, it will provide exactly enough wood to the temple kitchen for the entire two-year Paryaya term. Food plays an important part in the Paryaya festival, with tens of thousands of meals prepared in the Krishna temple kitchen every day. The incoming swami’s matha is responsible for all the cooking, which is all done in ovens fired by wood. Food, cooking utensils and huge brass pots are moved from the incoming swami’s monastery to the Krishna temple on January 17. At the same time, the outgoing swami shifts his cooking equipment back to his own monastery. Vegetables are brought in procession to the temple for the daily feast, annadhanam, served to all devotees.

VIVEKANANDA WAS OUTCASTED FOR HIS TRAVELS TO AMERICA

It is a little-known fact that Swami Vivekananda was “outcasted” by the Bengali orthodoxy upon his triumphant return from the Parliament of the World Religions in Chicago. The most dramatic consequence came in 1897, when he returned to Calcutta. The following is excerpted from A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda by Shailendranath Dhar.

In the evening of march 21, 1897, Swami Vivekananda and the Maharaja of Khetri, accompanied by a large party, paid a visit to the temple of Kali at Dakshineswar which, as is well-known to our readers, had been the scene of Sri Ramakrishna’s sadhanas and where the saint had lived for forty years.

In the reception given to Swamiji at Dakshineswar, as described above, there was a discordant note which did not reach his ears but which became loud soon afterwards and produced an unpleasant controversy in the press. Babu Trailokya Nath Biswas, the proprietor of the temple, who had been informed about the impending visit earlier in the day, had actually come to the temple and was present when the visit occurred but did not personally receive Swami and his party, which included a princely personage, viz., the Maharaja of Khetri.

“In an indirect way,” wrote Trailokya to The Bangabashi newspaper, “Swami and his followers were driven away from the temple, but not in a direct way as stated by Babu Bholanath [in the same newspaper]. I never ordered anyone to welcome Swami and the raja, nor did I myself do it. I thought that I should not have any, the least, intercourse with a man who went to a foreign country and yet calls himself a Hindu. While Swami Vivekananda and his followers were leaving my temple, Babu Bholanath Mukherjee told them that they would have no interview with me…. Your account of the re-abhisheka of the Deity [i.e., the evening worship was repeated to purify the temple] is perfectly true.”

A member of the family of Rani Rashmani protested in a letter which was published in The Indian Nation on April 12, 1897, against Trailokya’s claim that the temple of Kali at Dakshineswar belonged to himself. He asserted that it belonged as much to him as to any other descendant of the late Rani Rashmani and that the recent scandal would not have taken place had it been under the management of any other member of the family.

Notwithstanding well-meant efforts to ease the situation, the story of Swamiji’s alleged expulsion from the Kali temple gained ground. While The Bangabashi and other Bengali newspapers who opposed Swamiji kept it alive by continually writing on it, his old “friends,” the Christian missionaries, had a new dart in their quiver for attacking him. Dr. Barrows who, as we know, had lately arrived in India and had turned against Swamiji [having originally supported him at the Parliament], took it as one more proof of the correctness of his theory that Swamiji was not a true Hindu and had not preached Hinduism in America.

It seems that, even for some time after he had heard about the row kicked up against him by the orthodox people, Swami Vivekananda took little notice of it. His attitude was even one of defiance of these critics, as we find it expressed in a letter dated May 30, 1897, “Our books tell us that the practice of religion is not for a sudra. If he discriminates about food, or refrains from foreign travel, it avails him nothing and it is all useless toil for him. I am a sudra and a mleccha (a non-Aryan, a barbarian)–why should I worry about observance of these rules? What matters it to me if I take the foods of the mlecchas and the untouchables of Hindu society?”‘

A few months later, when he came to know about the propaganda that was being carried on by Dr. Barrows and the missionaries to the effect that he had been outcasted in India, he wrote on the latter point to Mary Hale on July 9, 1897 as follows, “As if I had any caste to lose, being a sannyasin!” He added, “Not only no caste had been lost, but it has considerably shattered the opposition to sea-voyage–my going to the West. … On the other hand, a leading Raja of the caste I belonged to before entering the order got up a banquet in my honor, at which were most of the big bugs of that caste … It will suffice to say that the police were necessary to keep order if I ventured out into the street! That is outcasting indeed!”

In earlier chapters we have dealt with the campaign of vilification carried on against Swami Vivekananda by the Christian missionaries and by Pratap Chandra Majumdar [of the reformist Brahmo Samaj] in America and also in India. In their present campaign they reiterated their old charge that he was not a true representative of Hinduism, bolstering it with the arguments they borrowed from the charge-sheet drawn up by the Hindu orthodox opponents of the Swami in their own campaign against him. There was something funny in Christian missionaries and Brahmo reformers who did not believe in caste attempting to belittle one for non-orthodoxy in such matters as eating un-Hindu food, dining with mlecchas, going on sea-voyage, etc.

THE KINDLY ELEPHANT

Krishna’s Subhadra is a hit with kids and adults alike

Subhadra’s day begins with a bath followed by a breakfast of cornmeal and kooragu flour. At 9am, after the temple puja, she receives a second meal–cooked rice seasoned with turmeric provided by the temple kitchen. A continual supply of palm leaves is available the rest of the day, plus whatever devotees offer. The 15-year-old elephant’s daily duties include leading processions once or twice, and giving blessings each evening from 4pm to 8pm. On festival days she leads the temple chariot and things get a bit more hectic. From time to time she must also greet visiting dignitaries. Unlike elephant duties in Kerala, she is not required to carry the priests on her back while circumambulating the temple.

Devotees come to see Subhadra after worshiping Lord Krishna in the temple. She is trained to give a blessing when offered a small coin which she adroitly collects with the tip of her trunk and passes to Unnikrishnan, her full-time mahout. Unnikrishnan, who comes from a family of mahouts, has cared for Subhadra for seven years. “She is very obedient and follows my commands without hesitation,” he volunteers. Her good health and clean surroundings are testament to his dutiful care.

Subhadra is very considerate of small children, gently touching them on their head with her trunk, which feels like a very large and dry tongue. Although she only gives the blessing when given a coin, she happily accepts food, such as bananas–which she does not share with her mahout but eats straight away.