In two decisions just days apart by the United States Federal Court of Appeals in San Francisco, California, a 103-foot cross on top of that city’s highest hill was ordered removed, while a ten-ton statue of the Aztec God Quetzalcoatl was allowed to remain in a San Jose city park. The seemingly contradictory August, 1996, decisions have provoked new controversy, and further appeals are expected.

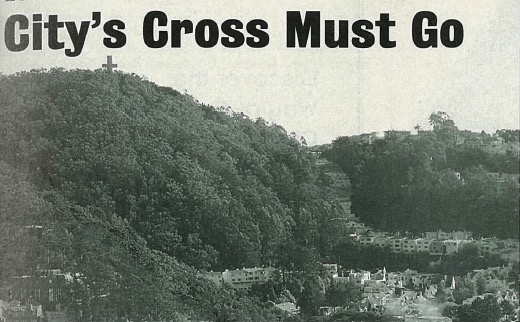

The Mount Davidson cross, as it is known, has been a southern landmark for San Francisco since 1934. In 1990 seven individuals of various faiths filed a lawsuit arguing the cross was a “pre-eminent symbol of Christianity” and alienated people of other beliefs. The first judge to hear their case dismissed it, but the appeals court ruled the cross did indeed violate the “no preference” clause in California’s state constitution. That clause protects the “free exercise and enjoyment of religion without discrimination or preference.” It is a much broader assurance of government neutrality than the U.S. federal Constitution’s First Amendment guarantee of separation of church and state.

In 1993, the same appeals court ruled the city of San Diego in Southern California had to remove two 35-foot-high crosses on public land. In doing so the justices set down five considerations in cases of public ownership. They are: religious significance of the symbol in question, size, visibility, absence of other religious symbols nearby and possible historical significance.

In ruling against the San Francisco lawsuit, Judge Diarmuid O’Scannlain wrote, “The Mount Davidson cross carries great religious significance. Indeed, to suggest otherwise would demean this powerful religious symbol. Thus, we conclude that its presence on public land violates the No Preference Clause of the California Constitution.” Further appeals to his decision are possible.

Many Christians were upset with the court’s verdict and hoped some way would be found to keep the towering cross standing. “I don’t think the rights of Christian people are to be thrown out,” said Rev. P.T. Mammen of the San Francisco Association of Evangelicals, “All of a sudden, are we expected to renounce our faith? Do only unfaithful people have rights in this city?”

On the other side, attorney Fred Blum, representing the American Jewish Congress, a plaintiff in the case, said, “The worst part of the city argument was that the cross represented San Francisco. What it told me is I cannot be a San Franciscan, because a Latin cross could never represent me.” Barbara Bergen, regional director of the Jewish Anti-Defamation League, commented, “We are gratified that the court upheld the principal of separation of church and state. We consider it fundamental to the protection of both majority and minority rights.”

A few months earlier the same court had ordered the removal of a 51-foot cross in an Oregon state park because it “clearly represents government endorsement of religion.” That cross had been challenged since its construction in 1965, and was ruled against in 1969. City officials then redesignated the cross as a “war memorial.” That ruse survived two more court challenges before the appeal’s court final ruling to remove it.

The same court’s ruling in favor of the Quetzalcoatl statue in San Jose (about 50 miles south of San Francisco) was based on their assessment that the figure had little “current religious significance,” as the Aztec religion is no longer practiced on a large scale. This mattered little to fundamentalist Christians who, according to newspaper reports, “contend that Quetzalcoatl was a blood-thirsty demon who demanded human sacrifice,” ignoring the fact that the cross is also an icon of human sacrifice. In the Aztec religion, the Quetzal bird represents the heavens and the coatl, or snake, represents the Earth. Quetzalcoatl was worshiped by the Mexican civilizations until the Spanish invasion 500 years ago. The San Jose statue depicts a plumed snake coiled upon a pedestal.

San Jose has a large number of Chicano residents originally from Mexico and Latinos from countries of Central and South America. The US$400,000 sculpture was commissioned by the city in honor of their ancestors. But that community is itself divided on the sculpture. Manuel Salazar, a devout Latino Catholic, said, “It is demonic. We wish not to be represented in this way.” But Valdez, a playwright, said at a meeting of supporters and opponents of the sculpture, “To those people that resist the true spirit of Quetzalcoatl, let me tell you, speaking as a Chicano, that we have had 500 years of the Spanish Inquisition. We don’t need another month of a Protestant Inquisition.”