With SARA SASTRA in Denpasar, Bali, NYOMAN WENTEN in California and RIMA XOYAMAYAGYA in Texas

Filmmaker Lawrence Blair, midway through documenting Indonesia’s indigenous peoples, planned to avoid Bali, with its international airport and luxury hotels. But “When I finally arrived in 1975, on the desk of the immigration officer who stamped my passport was an exquisitely woven offering of flowers with burning incense leaning against his ink pad. Outside, I noticed an even more elaborate offering affixed to the radiator grill of my taxi. For this was the day of offerings to active sharp and blunt objects of our lives, …thus ritually connecting the officer’s inkpad with the front of my taxi.” Bali–which means “offering” and is popularly known as the “Island of the Gods”–had cast its spell on Blair. It’s a religious oasis where two million Hindus, out of a 2.8 million total population, live and breathe their faith 24 hours a day.

Bali lies just below the equator in Southeast Asia, part of the world’s largest stretch of volcanoes. Peppered with mountains, lakes, rivers and forests, it has 2,147 square miles of fertile land and history. Legend states that the Supreme God, Ida Sanghyang Widi Wasa, created the sky for Gods, the Earth for animals and seas for fish. He decided to create man in an earthly paradise. Pulling a fish from the water, He held it to the light. Its tail became the Kutri peninsula, its gills Lake Bator, and its backbone the range of mountains shimmering across the length and breadth of the island.

Many have felt Bali’s blessedness–Hickman Powell, a 1930s visitor, called it a “vast wonderland” and the “embodied dreams of pastoral poets,” and India’s Jawarhalal Nehru immortalized it in the 1950’s when he dubbed it the “Morning of the World.” Adds Blair, “It wasn’t surprising that the rest of the world saw Bali as the living symbol of heaven on earth, where man and Gods, nature and spirits, the within and without, co-existed harmoniously in the best of all possible worlds. What did surprise me, was finding that the Balinese entirely agreed, and took the unusual position that the grass was indeed greener on their side of the fence.”

Tourists–1.2 million a year–have their impact. Rima Xoyamayagya, a recent visitor, says “Areas around big beach hotels have crime and a low vibration now.” A thousand hectares of rice fields are turned over yearly for development, much of it for tourism. You can’t drink the tap water, and when stepping out of a hotel you’re likely to be accosted by hawkers. So why do travelers flock to Bali? Many are eager to witness the non-Western, uninhibited Hindu culture which is Bali’s charm. And the Muslim Indonesian government, understanding the economic benefits, tries to maintain it in several ways. Hotels are restricted to certain areas. Foreigners wanting to live in Bali are also confined to special areas. Tourists aren’t allowed in the center of temples. And the rigidity of Balinese social structures keeps tourists at the “onlooker” level, where they are content to ooh and aah. Hinduism Today interviewed Hindu Balinese and outside visitors to understand what fosters Bali’s charm. Their insights are shared in the context of a day in the life of Balinese village housewife Men Parni, narrated by her nephew, Nyoman Wenten.

5am:First to arise, she fetches firewood, water at the family well, then makes porridge. After breakfast, her two children are off to school and her husband to the nearby rice field. Most Balinese eat very simply at home–and mainly rice. It’s consumed, using fingers, with a side dish of vegetables and tofu, a spicy chili seasoning made fresh daily, and soy sauce. A banana leaf is usually the plate. People eat little meat in everyday meals, deriving most protein from soy products, and more converts to total vegetarianism are appearing with the desire to eat pure food. Even though life is urbanized in Denpasar, Bali’s capital, six 16-and 17-year-old youth (we’ll call them the Youth Group) told Hinduism Today they daily “offer cooked food to ancestors, devas and buta kalas (evil spirits), worship at the family house temple and recite Gayatri Mantra.”

It’s hard work for Men Parni’s husband in the fields, but the inseparable religion (shrines to Dewi Sri, the Rice Mother, dot the fields) offsets hardships of a lifestyle largely unchanged since the 1600s. In the 1970s bureaucrats tried to impose the “Green Revolution” on Bali’s rice irrigation, but it failed miserably, and farmers reverted to their intricate “water temple” system.

8am:A festival is coming, so Men Parni makes decorations out of young coconut leaves for a couple hours. Then time to cook lunch, which her husband returns to eat. Before serving, she offers rice and salt to all corners of the house and the family temple. Dewan Nyoman Batuan, a painter friend of Lawrence Blair, observes, “You don’t need much in Bali, just enough to eat and to make necessary ritual offerings. Feeding the Gods feeds your soul as well.”

The Youth Group feels Hinduism fares better in Bali than in India, because it’s cared for by the government, the Hindu Parishad, teachers and village customs. Most schools have a Hindu religion teacher who, besides parents and priests, is the Balinese equivalent of a guru. Most girls wish to marry Hindus. The Group believes the next generation will be even stronger than now. In fact, Western visitors occasionally convert to Balinese Hinduism, as in the case of scholar Fred Eiseman: “The Central Hindu Dharma Committee approved. Then a pedanda (high-caste priest) at a Denpasar temple said prayers and administered a purification offering, bestowing the name I Wayan Darsana. I received a certificate from the committee signifying my religion.”

12:30pm:Naptime for Men Parni and her husband. Then she makes more decorations. Unless the wife has an outside job, her main duty is to make offerings and care for the house. She may gossip with a neighbor or help her conduct a home ceremony. Kids return from school and play gamelan instruments or help in the rice field. Young children are revered as divine. They’re carried everywhere, held in the protective arms (without ever touching the ground) of a family member until three months old.

Bali has an extraordinary sense of community, transcending Western ideals of liberty and individualism and putting cooperation above competition. Restaurant manager I Komang Budastra, 27, says this “keeps us from differentiating between rich and poor. By following individual ways, people don’t share.” When Nyoman Batuan invited Blair to build a home on his land, he said, “It’s not my land anyway. Only Gods can own land. Humans borrow it for awhile.” The whole village turned out to build Blair’s house.

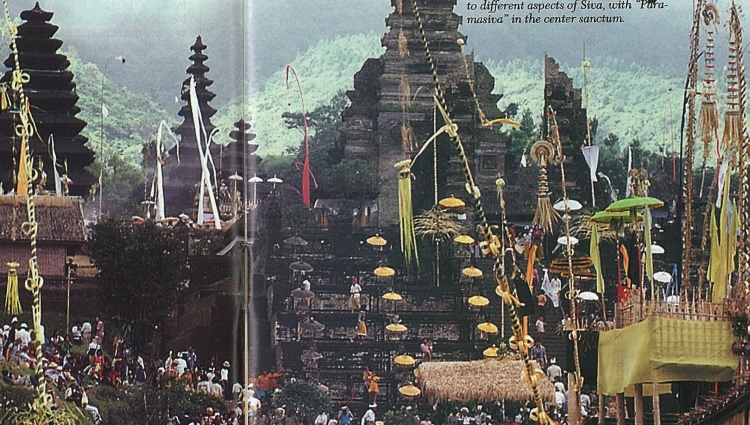

6pm:An offering is given to the home’s four corners and temple. Men Parni and her husband leave for their nightly dance performances in temples all over Bali, to which they often bring the kids. He is a drummer, while she is an opera dancer. Dances begin at 10pm and last till early morning. Bali has 20,000 public temples, and most homes have a family temple. Each celebrates its dedication anniversary, which is frequent, because the Balinese lunar year lasts just 210 days. It’s hard to miss a temple festival, because one occurs somewhere every day. But watch what you wear–modest clothing with a sash is the rule for everyone. Blair observes, “Food and entertainment is right in the temple. If my childhood churches were like this, I would’ve spent a lot more time in them!”

The Youth Group say they always observe at least five festivals: 1) Galungan, where deified ancestors descend to former homes; 2) local temple anniversaries; 3) Nyepi, or Day of Silence, during which the whole island shuts down–people stay home to meditate (tourists can’t leave their hotels), and lights are out; 4) Saraswati puja; and 5) Purnima–full moon. Miss Ayu Eka, 24, says she pays homage to knowledge on Saraswati Day. “I make offerings of yellow rice to my temple and books.” And children sweep schools with brooms to honor their place of learning.

Shadow puppetry, dance, theater, carving and other art forms are abundant. Nearly all arts are religious, because all life is religious for the Balinese. Painters aren’t possessive about their work, and even create many of their canvasses together. Nyoman Wenten, 53, describes the flowering of a dance artist. “My grandfather was an actor, puppeteer, musician and dancer. I began at age six by watching older dancers perform at my village, who I then imitated. My grandfather saw I was interested, and corrected my moves. One day he appeared with a costume and said, ‘Let’s go to the temple.’ I was scared. ‘I’ve never performed with an orchestra!’ He said, ‘No problem, you can do it.’ This was my debut, at age seven.” Girl dancers are at their peak at age 11, because they’re still considered totally heavenly, until puberty. One instructor, Ms. Utuwarthi, uses no mirrors for training. “If the inner dance is right,” she says, “it’ll show itself outwardly.”

With Bali’s powerful belief that religion is woven into every part of life, it’s no wonder that the Balinese Youth Group tells brothers and sisters worldwide: “Keep Hinduism, it’s the great religion. All must learn its essentials. We must be strong in faith and devotion. God will always bless us.”

With Sara Sastra in Denpasar, Bali, Nyoman Wenten in California and Rima Xoyamayagya in Texas

HISTORICAL BALI

ca 10ce: Indian traders bring Hinduism to the northern Indonesian islands.

ca 650ce: Visited by Indian literati, Balinese embrace Hinduism. Java and Bali royalty marry. Many Javanese Hindus immigrate to Bali as eastern Java’s Majapahit empire takes over Bali.

1478: Muslims overthrow Java’s Hindu Majapahits, making Bali a refuge for their Hindu nobles, priests and intellectuals.

1906: Dutch invaders attack Denpasar, Bali’s capital, massacre 3,600 Balinese and capture the whole island.

1950: Dutch are overthrown and Bali becomes part of the Republic of Indonesia.

1963: Bali’s highest peak, Mt. Gunung Agung, known as the “navel of the world,” erupts after a 120-year dormancy, killing 1,500 and leaving 85,000 homeless.

ca 1977: Television enters homes, offering first glimpse of world tourists come from.

1979: Eka Dasa Rudra, Bali’s most elaborate ceremony, held only once each century. Taking months to enact, it intends to achieve a balance of good and evil throughout the 11 directions of space.

BEYOND BALI’S FOLLIES

One professor’s contemporary take on things

Nyoman Wenten is an accomplished musician, actor and dancer living in southern California since 1972, where he teaches at the Institute of the Arts in Valencia. He returns to his village in Bali for three months each summer.

On spirituality in performing

There is more than just great talent. Spirits, Dewa Taksu, help the performers gain stage presence or charisma. In order to receive the Taksu, we must give offerings and recite mantras before and after every performance.

On tourism’s impact

Hotels make us shorten our dance from 25 minutes to five. If you dance at the hotel every night for a living, you don’t have a lot of energy, not the same soul inspiration as when you dance at the temple or for rites of passage like the tooth filing ceremony or weddings. Certain sacred dances shouldn’t be performed in hotels.

On village obligations and ceremonies

We have so many ceremonies that take so much time and money. People are too proud, spending hundreds of dollars and getting in trouble financially. I used to ask my mom, “Why do you make huge offerings?” She replied, “Well, the neighbor’s offerings are taller!” There is a movement now to simplify ceremonies, like holding collective cremations and tooth-filings.

On the strength of the next generation

Many families can’t afford to send their kids to normal schools, so kids go to the Christian schools and get converted. Our youth need to be well educated in Hinduism. They learn some in school, but just at surface level. They only get taught in depth every six months, so we need more frequent teaching programs.

On nonviolence and meat-eating

We have blood sacrifices. Balinese are educated to not hurt other living beings, so we must consider whether to continue killing animals. I hope we can slow down the offering of meat at temples. Recently, my friend Sreenivasan took me to a South Indian vegetarian restaurant in California, and I really enjoyed the food!

On corporal punishment of children

My aunt raised a cane to scare me, but didn’t strike me. Grandfather was different. He spoke compassionately and lovingly. Now he is the one I respect, because he had a different mentality for discipline.

I NYOMAN WENTEN, 23202 REDBUD RIDGE CIRCLE, VALENCIA, CALIFORNIA 91354-2037 USA