Interviews by RAMESH SIVANATHAN and RAJAKUMAR M ANICKAM, Malaysia

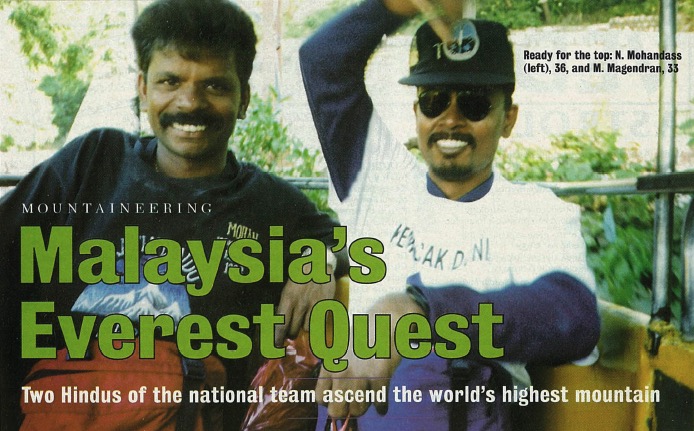

Thank God! Thank God!’ was the first thing I said when I set my foot on the top of the world,” gushed M. Magendran. On May 23, he and N. Mohandass became the first Malaysians (and likely the first Tamils) to reach the summit of Mt. Everest, 8,848 meters high. “Aum Namasivaya was in my mind all throughout my ascent,” Magendran told Hinduism Today. “Once on top, I prayed to all the Deities. I thought of our Prime Minister, our Everest team, my friends and the people of Malaysia who were praying for our success.” Magendran, Mohandass and their five Sherpa guides planted the Malaysian flag, “shouted into the wind” and celebrated their victory–for ten frozen-in-time minutes. The news was radioed down to the Malaysian base camp and relayed on live TV to a jubilant country. But the climbers knew the task was not over yet. Nearly everyone who perishes on Everest dies on the way down, not up. So they scrambled off the mountain to safety and within days were heros at a tumultuous welcome at Kuala Lumpur’s International Airport.

Mt. Everest has been in a deadly mood the last few years. In 1996 eight died during summit attempts, the worst year ever. By May of this year seven more had perished, including Nima Rinje Sherpa of the Malaysian team, who on May 5 fell into a 600-meter crevasse high on the South Face. One German and two Kazak climbers were blown off the North Face when 140-mph jet-stream winds dipped down onto the mountain as they descended from the top. More than 710 climbers from 42 countries have scaled Chomolungma, “Goddess Mother of the World,” as Everest is known in Tibetan, since it was first climbed by Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay on May 29, 1953. One hundred and fifty others have lost their lives. The odds of dying are one in six. At the highest elevations, the route is “littered” with bodies impossible to retrieve out of the ice or to carry down.

The Malaysian climbers’ arrival in Kathmandu fell auspiciously on the night of Mahasivaratri–one of Hinduism’s holiest days. Both Magendran and Mohandass observed the festival at Kathmandu’s Pasupathinath Temple. “Team member R.C. Ramakrishna, who has vast experience in climbing,” recalls Magendran, “told me to treat Everest as a sacred mountain and to do my prayers and mantras while climbing.”

The devout Buddhist Sherpas brought in a lama from a nearby monastery to bless everyone at Base Camp. “Some climbers just hung around,” narrated Magendran, “but I was sitting a few feet from the lama and praying.” Mohandass said, “When I was staying at Base Camp, I had a dream of Lord Ganesha who told me to do a lot of prayers.”

Prayer was definitely in order, for many expected a repeat of last year’s disaster. One-hundred-eighty climbers in 13 teams were gathered for the dangerous Southern Route, and another 150 climbers in 12 teams were prepared for the safer but more expensive-to-climb North Face. Eighteen countries were present. The Malaysian team was unjustly singled out by two professional guides for criticism as “inexperienced” and “under tremendous political pressure to summit.” It was strange criticism coming from the group who last year were chastised for taking completely inexperienced climbers to the top–some of whom died there. There was nothing reckless about the Malaysian strategy or ascent under the watchful eye of expedition leader Nor Ramlle Sulaiman and Captain M.S. Kohli, leader of India’s first trek to the summit in 1965. Half of the 25 teams, most led by professional guides, never made it to the summit. The Malaysians had originally hoped to beat the Indonesian team to be the first Southeast Asian nation on the summit. But under the legendary Russian Everest guide Anatoli Boukreev, the Indonesians arrived earlier.

Back home in Malaysia, wives and mothers were taking no chances with the climbers’ safety. In normal times, Mohandass’ wife Manimegalai, does puja twice weekly for her husband’s health, safety and longevity. “Then I heard in May that they might have to abort the climb because of bad weather. This was sad news to me. I thought there is no glory in my husband returning home without conquering Mt. Everest. So on Friday the 16th, I went to the Kottamalai Ganesha Temple and prayed that everything should be alright for my husband to climb the mountain and return safely. The next Friday I heard the news. Lord Siva was up there and let him return safely.” Magendran is unmarried, and his mother, uncle and friends similarly prayed for his success and safety, arranging special Murugan worship on May 23, the day of the ascent.

Reports of the climb sound like a soldier’s descriptions of war: long periods of boredom interspersed with moments of sheer terror. The team sat at Everest Base Camp for three months acclimatizing to the altitude and waiting for the rare break in weather which would allow an ascent. Nor Ramlle described it as depressing. “You have to sleep on ice, barren rock and snow. There is no life there, no birds, no trees. We had to resort to playing scrabble and dominoes, reading books and climbing nearby peaks.”

Four team members were selected for the final attempt: Magendran, Mohandass, Mohd. Fauzan Hj Hassan, 29, and Gary Choong Kin Wah, 39. Their first chance was May 9, but bad weather–and “bad weather” on Everest is really bad–forced a return to base camp. Time was running out, since the government would close the route on May 24. The team left again on the 18th and after further weather delays reached Camp Four at 1:30 pm on May 22. “There we rested,” reports Mohandass, “then left at 11pm for the summit. It was very cold, -30¡C (-22¡F) and the wind was at 80 km/hour (50 mph). Hassan and Choong Kin Wah succumbed to altitude sickness and turned back after reaching 8,400 meters.

“It took thirteen hours to reach the summit. The terrain was very steep, and the path was littered with bodies. The Sherpa was showing me each of the corpses and explaining to me how they died and who they were. Finally, I told him not to point out the bodies to me, and that I just wanted to reach the summit. We had to crawl the last section to the top because of the wind.” Twenty-five climbers from other teams reached the summit that day–auspiciously Vaikasi Vishakam, sacred to Hindus as the birthday of Lord Muruga and to Buddhists as the day of Buddha’s enlightenment.

The returning Magendran was ecstatic over their success. “For all Malaysians it shows racial unity, teamwork, that we could do anything if we work as a team and believe in what we are doing. People are very proud. There have been so many calls day and night. Many temples still ring me up to ask me to come to their temple because they had prayed for my successful climb.” A total of US$240,000 was awarded to the team; Magendran and Mohandass got $20,000 each.

Malaysia had planned the climb for ten years. The team trained intensively for the last three. Telekom Malaysia and other Malaysian corporations were the main sponsors for the program, which is part of the government’s “Malaysia Boleh!”–“Malaysia Can!” campaign. The Everest 97 project was a follow-up to the “Malaysia Cergas” campaign launched in the 1980s with the aim of encouraging the general public to participate in recreational and noncompetitive sports, with the hope of producing a healthy society. There are plans to scale Mt. Kilimanjaro in South Africa, Puncak Irian Jaya in Indonesia, Mt. McKinley in the US and Mt. Eiger in Europe. “Such expeditions are to showcase the Malaysia Boleh spirit,” said team leader Nor Ramlle