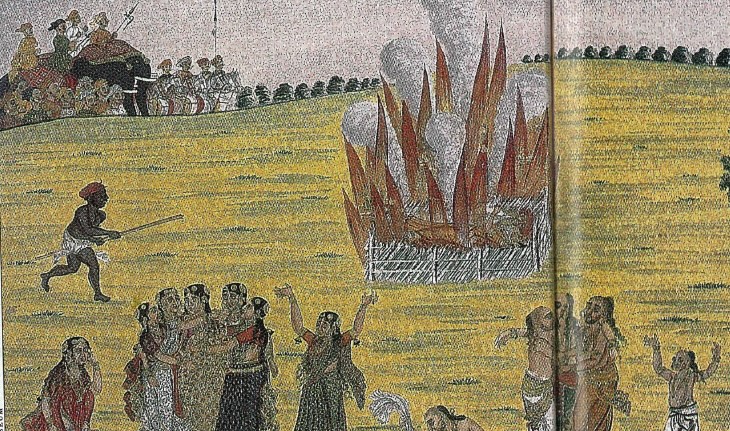

Madhu Kishwar, editor of Manushi magazine and a champion of the oppressed in India, offers her analysis of a proposed government ban on “sati temples,” some ancient, which commemorate instances of women burning themselves to death on their husband’s funeral pyre. This rare event, illegal since British times, still occurs from time to time, mostly in the state of Rajasthan. Madhu opposes any ban on sati temples, argueing that such laws will not change the circumstances that lead to sati, but may instead encourage other laws attempting to regulate religious belief and practice.

By Madhu Kishwar, Delhi

It has been a long-standing demand of feminist reformers to not only use strong measures to curb new satis from happening, but to also declare ancient sati temples illegal and shut them down. They feel sati temples glorify the sati cult, thus beckoning women to follow suit. I feel that it is indeed necessary to use all manners of persuasion to stop women from killing themselves, whether by way of ordinary suicide or sati. However, trying to close sati temples by force has the potential of setting into motion a very dangerous downward spiral.

Firstly, for all the so-called glorification of sati in certain regions, we have not witnessed anything resembling a sati epidemic. With all the sati temples in Rajasthan, extremely few women offer themselves for immolation, including those who might bow in reverence before a sati shrine. After Roop Kanwar’s immolation in 1987, there have been no more than a few cases of attempted self-immolations by widows in India. Most were averted by timely intervention. Even before the anti-sati act was passed, a very small number of women killed themselves on their husband’s pyres within the last several decades.

Taking an authoritarian route to social reform is mostly counterproductive. Today, one group demands the closure of sati temples because they violate the values of one community. Tomorrow another group might demand the closure of all Kali temples because they might see Her worship as idealizing vengeful aspects of femininity. Some others might want Krishna temples declared illegal because he was a polygamist. Still others might want Ram temples banned because he subjected his wife to a cruel test of her virtue by fire. There is indeed no end to this game of any self-declared group of social reformers seeking to discipline others into “approved” behavior and making them worship only certain “approved” Deities.

One of the great strengths of our civilization is that people are free to choose their own Gods, their own modes of worship. New icons are constantly invented without need for sanction from any hierarchical authority. Each village has its own preferred pantheon of Gods and Goddesses, with varied sets of qualities for which they are deified. For instance, Ram is valued because he was supposedly perfection incarnate. Likewise, Krishna is revered despite the fact that he deceived and played tricks on everyone, including his mother, lovers, wives, friends and enemies as part of an elaborate leela, or play. There are Goddesses like Parvati who are approached as benign mothers, symbols of happy conjugality and wifely devotion. Then, there are ferocious Chandi-Durga type Goddesses who strike fear in the hearts of devotees because any man who tried taming or desecrating them invited death in the most brutal manner.

Even Mahoba region has very recently created such an icon. To quote Smeeta Mishra Pandey in The Indian Express: “It was in March last year that I had visited Mahoba chasing yet another tale: The story of Ram Shree, the village woman who along with her brother and father killed her relatives. Shree was the first woman to have been given a death sentence after Independence. I found that villagers spent their evening narrating tales about Ram Shree. They often debated whether Ram Shree did the right thing. Shree had apparently killed her relatives because they had tortured her and beaten her up mercilessly. Women wondered why the court had any say in the happenings in their village. In no time, Ram Shree become a living legend. When the Supreme Court swapped her death sentence for life imprisonment, taking pity on her one-and-half-year-old daughter, the villagers believed the Goddess had come to her rescue.” In time a temple to Ram Shree may well come into existence.

The coexistence of Ram Shree legends shows that the culture of this region allows for diverse ideals and icons to be celebrated simultaneously. The same people who worship Sita or Roop Kanwar as symbols of wifely devotion are also capable of valorizing Durga-like behavior by ordinary village women. In Mahoba town, a Radha Krishna temple coexists with a school and a sati temple built in the 1930s–all in the same small complex.

In the Hindu tradition, there is no sharp divide between Divine and human. On the one hand, Gods come to Earth as varied human avatars to share the trials and tribulations of ordinary human beings. On the other, human beings can easily achieve divine status by living extraordinary lives and displaying inspiring qualities. Numerous village Gods and Goddesses in India are creations of this latter process. Deification, though, is not confined to the human form of creation. We sanctify various living and nonliving beings–cows, trees, elephants, snakes, mice, monkeys and even rivers, stones, mountains, earth, sun, moon and winds. At the same time, in some states, like Tamil Nadu, there are temples where popular film stars are enshrined as Deities.

Those who have tried to cure us of polytheism and make us subservient to the dictates of monotheistic faiths have inflicted a great deal of violence on our people throughout this last millennium. Let us not become willing agents for carrying that legacy forward to the next.

As long as sati shrines coexist with Durga and Yogini temples, as long as Parvati is not forced to repress her Kali form, as long as none of our Gods dare claim perfection and demand the banishment of others, we will continue to value tolerance, dissent, diversity and respect for different ways of doing and living and to have regard for the diverse species that inhabit this Earth and life forces that coexist in this universe. As long as our people feel free and empowered to choose their own Gods and Goddesses, they will respect the choices of others as well.

Those who wish to arrogate to themselves the right to subject other people’s modes of worship to an arbitrarily determined qualifying criteria–no matter how well intended–can easily veer towards Stalinist forms of repression or trigger off counterdemands for more censorship. If I demand a ban on sati worship through coercive means, others can very well demand a ban on Manushi because it advocates stigma-free divorce. To safeguard my own freedom, I have to respect that of others.

However, as emphasized earlier, the call for state intervention is valid when there is evidence of force being used to make someone adopt a pernicious tradition, or when violence is committed in the name of religion and social custom. Invoking laws to deal with crime is perfectly legitimate, but using the danda (“stick;” the authority) of the police, and threatening imprisonment to force a change in cultural values, inevitably leads to backlash.

Real reform lies in creating viable options which are easily accessible and help women move out of dependence. We have to have faith that the vast majority of people tend to act in self-affirming ways when circumstances don’t constrict their choices. But nihilistic acts, such as sati, come easily to defeated people whose life is a long, arduous struggle without hope. 1Ú21Ú4

Madhu Kishwar, New Delhi, is editor of Manushi, India’s leading magazine on human issues, especially women’s rights. She is an erudite activist working effectively to raise the quality of life in India.

For subscription rates or letters to the editor, write to: Manushi, c/202 Lajpat Nagar 1, New Delhi, 110024 India, e-mail: madhu@manushi.unv.enet.in, or Manushi c/o Manavi, PO Box 614, Bloomfield, New Jersey 07003.