By Anthony Peter Westbrook

The modern era has brought changes to many aspects of Indian culture, and music is no exception. For example, age-old methods of transmitting musical training from guru to shishya (disciple) are now being supplemented by music departments in modern Indian universities. But how are the traditional spiritual values of Indian music affected by this change? An ideal person to respond to this is someone who has been instrumental in both.

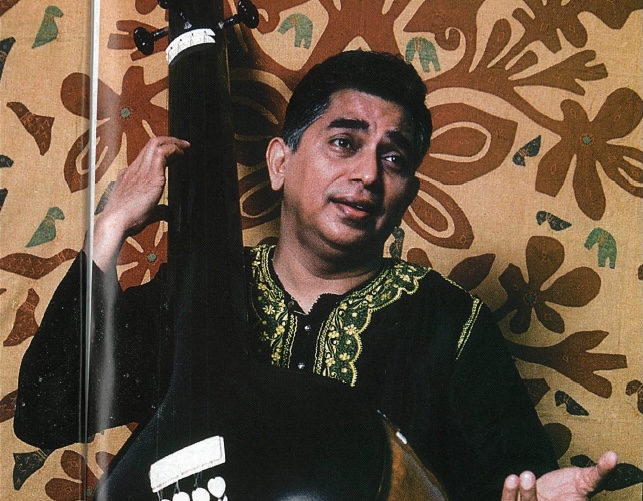

Eminent vocalist Pandit Vidyadhar Vyas gained purely traditional training at the feet of his father, Pandit Narayanrao Vyas of Mumbai, a fine vocalist and a senior disciple of the renowned Pandit V.D. Paluskar. Today, as Vyas concertizes throughout India and the world, he adheres strictly to the traditional aesthetic principles of the Gwalior school, or gharana, that Paluskar so ably revived. But Vyas is also an accomplished educator. He is deeply involved in passing on the tradition of Hindustani music as head of the music department at Mumbai University, supporting academic research and the development of programs to expand music education in India. Apart from his work in Mumbai, he has been a guest lecturer at many US universities, such as Wesleyan, Northern Illinois, San Diego State and Colgate. In Europe, he is responsible for the Hindustani vocal music program at the Rotterdam Conservatory, and was one of the guiding lights behind their recent Raga Guide project. [HT, January, 2000]. His new CD, Colors of the Night, (71min., us$15, Simla House, Inc.) presents a stellar 1994 performance at Colgate.

During his recent visit to Maryland, I asked Pt. Vyas about his background, both musical and religious.

On family background and upbringing

My grandfather, Pandit Ganesh Vyas, was one of the leading pravachan acharyas. These were the preachers attached to the temple of the Goddess Mahalakshmi at Kolhapur, in southwest Maharashtra, a very famous place. His “pandit” title was a religious one. He practiced religion, preached religious thoughts and so forth, but he was also an amateur artist. He used to play sitar, so that love of music came to my family through him, and then it was passed on to my father and uncle. Later they became students of Pandit Vishnu Digambar Paluskar, a music missionary, a great artist who was engaged in the social revival of art and artists at that time. The whole family were kirtankars. Kirtan is a form of music that tells stories of Gods and Goddesses and whatever those Deities stood for. The kirtankars preached morality and spread a spirit of devotion in the society.

I am Hindu myself, and I feel that Hindutva, being a Hindu, means that one is looking with that outlook towards life. Being Hindu does not depend upon a particular ritual, where only if you be this and follow this, then you are a part of it. If you don’t observe these, still you can be very much Hindu. All these blessed tenets of Hinduism–tolerance, being true to what you are doing, true to yourself?all these virtues attributed to Hindu philosophy create a way of life. I go to the temple, but I don’t go regularly in the sense of going to church on Sunday. I don’t have the kind of regularity that on a particular day I feel I must go. But if I pass on some road and there is a temple nearby, I would like to go to the temple and just go to the Lord and come back. So in this way it is a way of life. It is your own feeling. Above all, though, I feel that the strength of Hinduism is in its tolerance, respect for the inner God.

On the spirituality of music

I don’t equate music with religion, although it has spirituality in it. Music has to have a universal appeal that rises above religion and religious practices. Indian music is definitely on that level. Spirituality is an important aspect of music, and I try to sing with that feeling. Many times I see my listeners also coming to this same level, though they are listening and I am singing. The experience is that of bliss, ananda, as we call it–this creation of ananda, getting oneself immersed into that feeling of ananda. It is even more than spirituality; it is a feeling of bliss.

On the tradition’s longevity

With the development of so many media, all kinds of music are readily available. When you find all kinds of music around you, then naturally you are attracted towards whatever interests you most. Still, there is this slowly and steadily increasing group of young students coming towards classical music. They are learning and listening to classical music because they are attracted to it, not because someone like a father says, “I like classical music so my child should also learn classical music.” There is this welcome sign that, yes, students are getting interested in listening and learning. Even people in their middle age feel that now they have more time for music.

However, there is some apprehension. I feel and I see that talented students nowadays have less patience. Classical music requires learning over a longer period of time and at the same time sincerity towards practice–getting your concentration deep into the art, thinking of it and devoting your attention to the creativity in the art. That requires patience. In this fast world with its fast media, if you have talent, there are so many temptations to just get into this light music and get name and fame just like that. They are attracted because of the sheer rhythmic domination of that kind of music. So people are lured into these things, and they are not able to be good classical or traditional music performers.

There are two sides to this. We may think that it is pulling people away from the classical towards these different cultural aspects. But I don’t think that is the case. Those who are deeply rooted in their culture will not be so easily pulled away from their traditions. I see that, after a while, youth are turning away from that kind of music and coming back. I think the fertile roots in India are maybe a little deeper.

Art has to be dynamic, otherwise it would not go on and on; it would become a museum piece. Art, in order to be vibrant, to be pushing and going further, has to be dynamic. All these experimentations towards dynamism, in the test of time, if they are really good, they will conform to the ongoing ways of life and culture. Otherwise, they will die out. These trends have been there at any given point in history, also.

On the performance of ragas

There are those musicians who mint a new raga every day. But those ragas that have stayed, that is the test of time again. I know more than 150 or 200 ragas, but it doesn’t mean that I sing them all. In order to sing in a raga, to really attain its depth, you need time, concentration and practice. I remember my father telling me that his great guru, Pandit Balakrishnabua, the grand old man of the Gwalior tradition, felt that in one lifetime, if you mastered two, four or five ragas, even that is a great achievement. The raga, going deep into the raga, getting the feeling of the raga, getting to know what you require in the raga…it is like an ocean, a deep ocean.

Vyas’ Colors is superb recording. His expositions of Raga Yaman–arguably the most beautiful raga–and Raga Nand are sublime, introspective and at times delightfully playful. Vyas can also be heard in a 1991 studio recording from India Archive Music performing ragas Malgunji and Bhairavi. I asked Vyas what would happen if music were removed from the world. He exclaimed, “It would be chaos! People would go mad. It would be total chaos, and ultimately the destruction of everything!”

Simla House, PO Box 1229 Woodstock, New York 12498 www.simlahouse.com. India Archive Music, 2124 Broadway #343, New York, New York 10023. e-mail: indiaarcmu@aol.com.