By Tirtho Banerjee

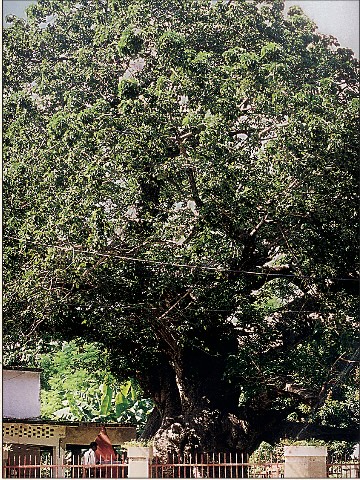

Nestled in the serene woods of Barolia village near Ramnagar in the Barabanki district of Uttar Pradesh, India, a lone Paarijat is believed to be the only living example of its species in the world. The huge tree spreads out in a circle about 50 feet wide and reaches a height of 45 feet. The trunk measures 27 feet in diameter. During August, white flowers bloom, emanate an overwhelming fragrance and turn golden red on drying.

Locals relate a lot of good omens to the tree and worship it on religious occasions. They see Paarijat as a kalpataru, a wish-fulfilling tree. One who sights Paarijat’s rare flower is reckoned very fortunate. On Basant Panchami day, a fair is organized here that draws many tourists.

The bizarre rarity of the Paarijat has drawn botanists from different parts of the world, and the government of India to issue two stamps in its honor. It bears no fruits or seeds, and all efforts to grow specimens elsewhere have gone in vain. Researchers from all over the globe, after extensive study, have placed it under a special classification. They wonder at the origin of the Paarijat.

Legends have it that Paarijat is one among the 14 gems that issued forth at the samudra manthan, the Churning of the Ocean of Milk in ancient times, whence also came the nectar of immortality. The Gods took the tree to heaven where it embellished the chariot of Lord Indra. Haribans Purana says that the Pandavas brought the tree down from heaven during their exile and offered 125,000 of its golden flowers to Lord Siva to win victory in the forthcoming battle.

While religious people across India know of this tree, it was only through the efforts of Baba Kashidas, Manzoor Miyan, Shiv Singh Saroj, editor of Swatantra Bharat, and the ex-governor of Uttar Pradesh, Vishnu Das, that Paarijat is now known to the world.

In the early 1960s, the forest department planted many eucalyptus trees around the Paarijat as part of an afforestation drive. It started shrinking. Experts from Nainital discovered that the Paarijat was dying because of water deficiency. Subsequently, the eucalyptus trees were uprooted, and the Paarijat regained its glory.

In recent times, in spite of the fact that the Indian government has declared the tree a protected one and released two Paarijat stamps, it has done little to care for it. Botanists are again raising alarm over its condition. Experts of Narendra Dev Agricultural University contend that the concrete platform around the tree is causing decay. Purshotaam, an employee of the forest department who looks after the tree, says it has shrunk substantially over the years.

The tree has been fenced, and people are allowed to touch it only on Tuesdays. Unfortunately, tourists have engraved their names on the trunk, damaging it permanently. The tree is home to many birds, including pigeons and parrots. The spontaneous music of the birds accompanied by the soothing comfort of the tree’s shade has to be experienced to be believed. But if the slow decay and neglect of the Paarijat continues, man may one day bereave its loss.

Contact:Tirtho Banerjee, 131 Rabindra Palli, Faizabad Road, Lucknow, 226016 India