By Daniel McGuire

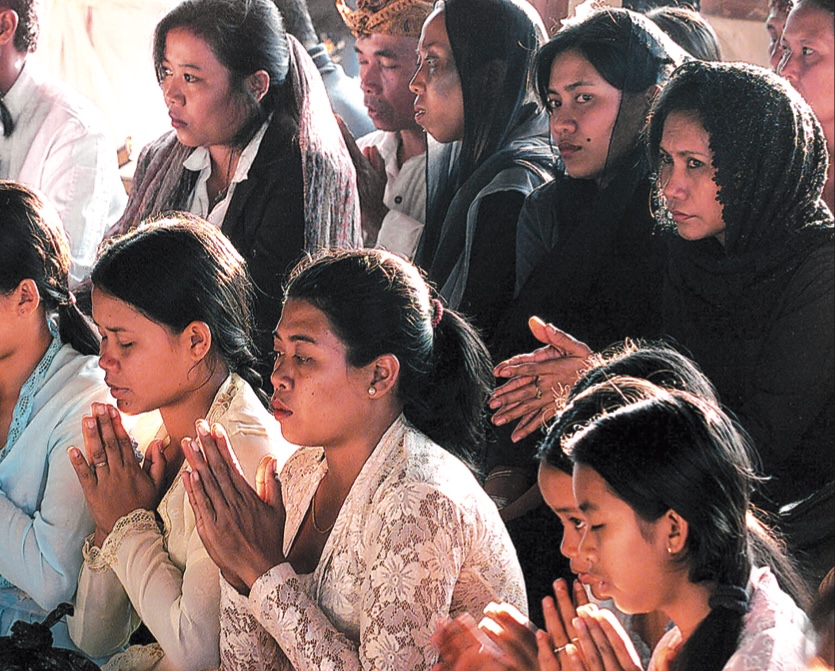

The Muslims have jihad, but we Balinese have puputan.” The person speaking is Rai, a young Balinese Hindu who works as a driver. It’s part of the reaction here to the horrific car bombings at Kuta beach, October 12, 2002, which killed 180 people, mostly foreign tourists, and has been blamed on Muslim extremists with connections to Al-Queda. In the uneasy days following the attack, Balinese Hindus and Balinese Muslims kept a cautious distance from one another, both wondering if the bombing might turn this legendary tourist spot into a battleground. Though Bali has been fairly peaceful in recent years—even maintaining calm when the rest of Indonesia fell into riots and chaos in 1998—the tension was now more acute, and Rai’s words made me uneasy. Puputan is a Balinese word that refers to a series of suicidal attacks made on Dutch colonial troops around the turn of the century. Balinese royalty—men, women and children—marched into battle with only ceremonial kris daggers against heavily armed Dutch forces. Hundreds died in these futile attacks, but they served their purpose. Demoralized and shaken, the Dutch withdrew from Bali and allowed Balinese self-governance for the remaining years of their reign in the Dutch East Indies.

That Rai could even envision an all-or-nothing battle for Balinese culture against Indonesian Muslims—whom he equated to an occupying force—indicates a sea change in thought. Certainly there is no historic precedent for this kind of thinking in Bali, where Muslims and Balinese have always lived side-by-side in relative peace. But as war has begun in the Gulf as I write, coupled with religious and ethnic conflict between Muslims and Christians that has claimed the lives of more than 10,000 across Indonesia since 1998, the unthinkable becomes possible.

The predominantly Hindu island of Bali is separated from the predominantly Muslim island of Java by a narrow channel only 200 meters wide. Each day, thousands of people cross this channel in both directions. Trucks and busses are loaded on barges that ply back and forth across this narrow stretch of water. The obvious idea of building a bridge between Banuwangi, the easternmost town in Java, and Gilimanuk, the westernmost town of Bali, has beenraised again and again over the years, only to be met by strong opposition from the Balinese side.

The Balinese Hindus, a minority in Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim nation, worry that they would be overrun by poor Javanese flooding the labor market of their world famous tourist industry. Perhaps just as important is the symbolic problem of a bridge. The Balinese identity exists in contrast to the Javanese Muslim “other,” and a bridge, no matter how practical, would undermine that sense of identity.

Bali has managed to maintain this sense of identity as well as territorial integrity throughout history. Muslims have never succeeded in invading Bali, though Bali has attacked and occupied both eastern Java and Lombok. In the 14th century, Javanese mercenaries to a Balinese king were given land in Gelgel, near Klungkung. This village still exists and is home to Bali’s oldest Muslim community. Traditional Javanese Islam, a blend of Sufism mixed with animist and Hindu concepts predating Islam, shares common heritage with Bali. The two largest Muslim organizations in Indonesia, Muhammadiah and Nadhatul Ulama, preach tolerance towards Balinese Hinduism by referring to the surah al-Kafirun verse of al-Quran, “Your religion is your religion; my religion is my religion.”

Social and economic ties between the communities are also strong. Visit the traditional market in Badung and you will see sheaths of coconut leaves that are woven into a wide variety of offerings used by Balinese in religious ceremonies. These coconut leaves are imported and sold in Bali by Javanese Muslims. Balinese and Muslims frequently marry, and in some villages the local brand of Islam is so mixed with Hinduism that the Muslim farmers make offerings to Dewi Sri, the Goddess of rice. Hindu boys attend their Muslim friend’s circumcision ceremonies, and Muslims in some areas adopt Balinese Hindu first names. It is not uncommon to meet a Muslim with a name like Ketut Ahmad Ibrahim.

In recent years, however, orthodox or revivalist Islam has been on the rise throughout Indonesia, which seems to be polarizing the Hindu and Muslim communities. Hadrami communities in Indonesia, people of Yemen decent who claim as birthright an orthodox knowledge of Islam, along with the Internet and current political and social influences, push Muslims in Bali to construct a self identity as a Mukmin among Kafir (believer among unbelievers), which is perceived by Balinese as social discrimination. “This has led to a growth in Bali of a parallel religious revivalism among Hindu-Balinese who increasingly see themselves as ‘Hindus’ globally opposed to ‘Muslims,'” says Nazrina Zuryani, a Muslim scholar living in Bali.

Balinese Hinduism is very different from Hinduism as practiced in India. Balinese Hinduism is Saivite and Buddhist tantric based. The caste system is not strong, but rather a clan-based system takes preeminence. Balinese believe in reincarnation, especially that they will be reincarnated back into their own families. While these aspects of Balinese Hinduism remain strong, there is a strong interest in the Hinduism of India, with India substituting for Mecca as the holy land.

In another example of parallel thinking, wealthy Balinese are signing up for package tours to the subcontinent in order to bathe in the Ganges and visit sacred sites. Many Balinese, like the driver Rai, are also taking a militant attitude towards Indonesian Muslims. One of the most notable is the psychiatrist Dr. Luh Suriyani, who, since the relaxing of censorship in 1998, has written columns in the Bali Post against interfaith marriage, as well as offering up his assessment of the “psychological propensity” that Muslims from Lombok have for being thieves.

The most telling change in Bali since “12 October,” as the bombing is called here, is the fact that there are far fewer Javanese on Bali. The construction industry has come to a halt, since most of the poor Javanese who held those jobs have returned to Java. Try to find a peddler of Bakso—beef soup which Balinese Hindus eat—and you are in for a long search. Most peddlers have packed up and gone home. And the price of coconut leaves for Hindu offerings is now 50% higher.

The vanishing of Muslims came about not through violence against Muslims, something very much feared in the days following 12 October, but through passage of laws that hit the pocketbooks of non-Balinese. All Indonesians are required to carry a state-issued identity card, known by the acronym of KTP (Kartu Tanah Politik). Since 12 October, some regencies in Bali, particularly Jembrana and Badung, have required that all non-Bali residents living within their borders apply for another identification card, a KIPP (Visitor’s Identity Card), which must be renewed every three months for a fee of up to us$45. In a country where a monthly wage is around $30, this new requirement provides more than enough incentive to return to Java.

That, of course, is the idea. With the tourist industry devastated since 12 October, and more native Balinese out of work, many regard the passage of these new policies as a preemptive measure to mollify recently unemployed Balinese and prevent them from venting their frustration on employed outsiders, even when those outsiders take jobs that the Balinese don’t want.

The idea of Bali’s being hit by the kind of ethnic and religious violence that has ravaged other areas of Indonesia seems unlikely to casual tourists whose only knowledge of Bali comes out of visitor industry brochures that always equate the word “Bali” with “paradise.” Infact, Bali’s recent history is full of internal strife.

The most obvious example, rarely discussed even to this day, is the anti-communist massacres of 1965, which is believed to have killed over 500,000, five percent of the population, including 100,000 in Bali alone. Initially, villagers were organized into groups by the Army, who then turned them loose on villages thought to be communist. Much of the work was done using only machetes and samurai swords left over from the Japanese occupation. The killing ultimately got so out of hand that the Army then needed to institute martial law to bring it to an end. To this day the ’65 period is rarely discussed outside academic circles.

One of the most disturbing developments since 12 October is the growth of Balinese militia groups called pecalang. Pecalang were originally conceived of as a kind of traditional police force to serve as security for religious events. They became further militarized by the political parties who then began to use them to protect political events. Now, nearly every village has a group of pecalang, mostly out-of-work youths, who have recently begun “sweeps” in search of residents without proper KIPP credentials. As was the case in 1965, pecalang often enter agreements with neighboring villages’ pecalang groups to mutually “sweep” each other, a system meant to promote impartiality, but a system that also prevents a militia member from showing sympathy to one’s own neighbors.

It should also be pointed out that extra-communal violence, mob killings of petty thieves, for example, are fairly common in Bali and all over Indonesia. No precise figures are kept, and such events are rarely reported even in local papers, but nearly everyone who has spent any time in Bali has a story to tell.

Just recently, an expatriate living in a village not far from the center of Bali’s capital witnessed a group of pecalang capture and kill two Muslim boys from Lombok. The boys had been accused by a villager of theft, though no stolen goods were found on their persons. The boys were approximately 12 and 14 years old. Police appeared after the fact to bring the bodies to the morgue. None of the pecalang was arrested. The expatriate’s son—also a boy of 14, witnessed the murders, and apparently has been seriously traumatized by the event.

While the potential for violence in Bali is quite real, there are many other factors that may help prevent large scale violence from erupting. Indonesia’s Military Command center for the East Nusa Tengara region is in Bali, and the military, which owns a number of tourist hotels, has a vested interest in keeping a lid on violence. Both Muslims and Hindus have too much to lose if Bali’s tourist industry is further hit. While Balinese Hindus are a majority on Bali, they still represent only two percent of Indonesia’s population, a figure that does not favor confrontation. Still, with the tourist economy in shambles and war in the Gulf in progress, pressure on relations between Muslim and non-Muslim in Indonesia is likely to escalate. For the time being, however, détente remains.

Daniel McGuire has been visiting Bali since 1984, and now has a home in Denpasar. he works as a writer, filmmaker and hatha yoga teacher. He is married to a Bali-born medical doctor, Injil Abu Bakar, who is medical coordinator for the survivors of the 12 October bombing incident in Kuta Beach. Daniel has also been working closely with the indonesian bomb victims, and involved in rehabilitation and job training for these patients. contact:dan@ashtangabali.com

Indonesia

The name Indonesia derives from Indos Nesos, meaning “islands near India.” The country is the largest archipelago in the world, with 17,508 islands spread over an area the size of the United States, and it is the fourth most populous nation on Earth.

The 216 million people comprise 365 ethnic and tribal groups, the principle ones being the Acehnese, Bataks, Minangkabaus (on Sumatra); Javanese, Sundanese (Java); Balinese (Bali); Sasaks (Lombok); and Dani (Irian Jaya). There are 583 dialects spoken across the islands, with Bahasa Indonesia as the official language. Indonesia, 87 percent Muslim, is the world’s largest Islamic country. Nine percent of Indonesians are Christian and two percent are Hindus.

The national ideology, Pancasila (“Five Principles”), is enshrined in the preamble of the 1945 constitution, set down in the declaration of independence from the Netherlands on August 17 of that year. The Pancasila are: belief in one supreme God; humanitarianism; nationalism expressed in the unity of Indonesia; consultative democracy; and social justice. The country’s motto is “Bhinneka Tunggal Ika,” which means, “Unity in Diversity.”

Balinese call their faith Agama Hindu Dharma, an amalgamation of elements from Hinduism and Buddhism, mixed with indigenous customs. They produce a colorful mix of ritual and doctrine dominated by two Hindu epics—Mahabharata and Ramayana—and the trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Siva; most temples being dedicated to one of the three. Affinity is shown by an old Mahayana Buddhist poem composed in Java: “The one substance is called two, Buddha or Siva. They say it’s different, but how can it be divided by two? Such is how the teaching of Buddha and Siva became one. It’s different, but it’s one; there aren’t two truths.”

Bali itself holds three million people, and 95 percent are Hindus. Tourism is Bali’s biggest industry, generating 67 percent of its gross domestic product. Before the bombing, Bali was hosting 1.5 million tourists a year.

Many have been awed by Bali’s blessedness. Hickman Powell, a 1930s visitor, called it a “vast wonderland” and the “embodied dreams of pastoral poets.” Filmmaker Lawrence Blair wrote, “It wasn’t surprising that the rest of the world saw Bali as the living symbol of Heaven on Earth, where man and Gods, nature and spirits, the within and without, co-existed harmoniously in the best of all possible worlds. What did surprise me was finding that the Balinese entirely agreed, and took the unusual position that the grass was indeed greener on their side of the fence.”

A constant threat in Bali is earthquakes and volcanos. An 1830 eruption devastated much of the island. In 1917 there was a severe earthquake, and in 1960s eruptions killed 1,500 people and left tens of thousands homeless. The latter eruption was blamed upon the government’s attempt to hold the Eka Dasa Rudra ritual, normally held once in a hundred years and scheduled for 1979, in 1963 instead. The ritual was canceled and held properly sixteen years later.

Tiny paradise:Bali, 55 by 90 miles, is about the size of Connecticut. It’s one of 17,508 Indonesian islands extending 3,200 miles east to west and 1,100 miles north to south.