BY KUMUD MOHAN

During vedic times, most children were taught at home by their parents. Sons apprenticed with dads, and daughters learned from moms. As these kids became adults, they helped to mold a personalized family tradition. However, for a few young people showing potential in fields requiring special instruction such as music, dance, art, medicine or the priestly crafts, gurukulams were established. A gurukulam (literally, “teacher’s family “) is a place where students live and learn in residence with a highly accomplished teacher in a specialized field. Although gurukulams can theoretically exist for the education of boys or girls in any skill, they are most traditionally established to instruct young men of the brahmin caste in the performance of Vedic priestly rites and the practice of religious discipline. To keep up with the needs of modern times, most of today’s gurukulams add a more secular teaching curriculum, including even computer classes.

The Shrimad Dayanand Vedarsh Mahavidyalaya of Gautam Nagar in South Delhi is one of approximately three hundred gurukulams still in existence today in India. It was first established some 70 years ago by a Hindu holy man named Swami Sacchinanda Yogi. Although it flourished for a number of years, it began to suffer for lack of sufficient patronage after India’s Independence in 1947 and finally closed in 1961. It was, however, reopened in 1979 by Acharya Haridev, and has been successfully functioning as a non-profit school ever since.

The one-acre campus of the Mahavidyalaya provides boarding and education for about 250 resident male students. To qualify for admittance, teenage boys must have at least a fifth-grade education, but no one is denied admittance due to caste, race or religion. Students come from all parts of India, including Assam, Bengal, Maharashtra, Orissa, UP, Bihar and Karnataka. Over 60 percent of them are very poor. Some are tribals or “untouchables.”

Poverty-stricken parents pay about $10 a month for their boys to live and learn at Mahavidyalaya–less than they would spend on them if they were staying at home. This nominal fee includes food, clothes, housing, books, medicine and instruction.

Admission to the Mahavidyalaya is formalized with an ancient ceremony called the upanayan, during which the tying of a sacred white thread across the left shoulder of the young student formally marks the beginning of his Vedic education. This ceremony also equalizes the status of the students, irrespective of their background. At this time their heads are also shaven.

The ashram raises its own cows. Meals consist of milk, dal, chapatis, vegetables and rice. Spices like ginger and cloves replace onion and garlic, which are believed to stimulate the instinctive nature. Fruit and yogurt, being costly, are included once or twice a week. Delicacies like puri and halva are served two or three times a month, usually when contributed by donors.

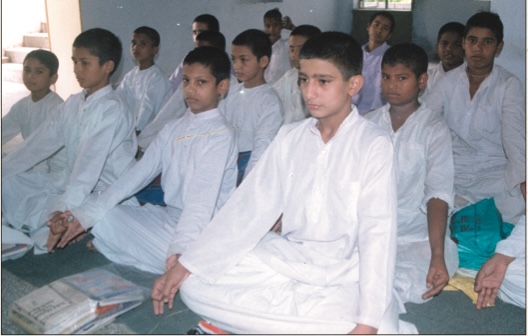

Each day begins and ends with hatha yoga, meditation and worship at the havan, or fire ceremony. The other daylight hours are tightly packed with work, service and classes. First priority is given to instruction in the performance of temple ceremony, but all resident students also learn mathematics, science and three languages: Sanskrit, Hindi and English.

Teachers and students share the same meals, wash their own clothes, sleep on the floor and follow the same demanding schedule. On the seventh day, Sunday, the only concession made is that formal education is replaced by sports and carefully monitored television.

Unnecessary contact with outsiders, considered a distraction to study, is not allowed. Students may occasionally communicate by letter or telephone according to individual requirements, although such communication is discouraged. There are no holidays, except an annual one-month summer vacation. Spartan simplicity defines the schedule, but most students adjust to it over time. Those who can’t or won’t usually drop out within the first two or three months.

There is no physical punishment of a violent nature in the gurukulam. “We discourage and disallow physical punishment of any type in the Vidyalaya, ” explains Pradhanacharya Haridev, the principal, “We believe in ahimsa, or nonviolence. Physical punishment would just lead to resentment and reinforcement of the fault rather than to the reform of it. So, normally, we point out the consequences of a child’s actions to him and encourage him to do some self-searching.”

Approximately 20 shastris and acharyas graduate from the Vedarsh Mahavidyalaya every year. Some become lecturers, writers and researchers. Others become purohits, conducting religious ceremonies, such as weddings. A few set up Vedic schools in India and abroad. Many continue to perfect themselves in the art of mantroccharana, the oral recitation of the Vedas.

Although it may be said that for now the ancient gurukulam system is alive and well, its future is undeniably fragile. Modern times militate against its austerity, money is always in short supply and mastering the ancient Sanskrit language is certainly not the prestigious aspiration it once was. Still, well-wishers of this ancient heritage hope for the best and pray that at least a few good, young men might be allowed the opportunity to spend their impressionable early years wisely –strengthening body, mind and character through discipline, study and restraint, according to the Vedic ways of old.

For more information please e-mail kumudmohan@hotmail.com or write: Kumud Mohan, 28 Anand Lok, New Delhi-110049