BY SONIA SWEET KUMAR

I was reminded, at times, of my wedding preparations–organizing a long list of people to invite, stocking the house with disposable plates, glasses and utensils, making food arrangements, arranging sleeping accommodations for out-of-town guests, pulling old pictures out to display, arranging for a priest and devotional musicians. But this time, my family and I were preparing for another sacrament–my father’s end of life and last rites.

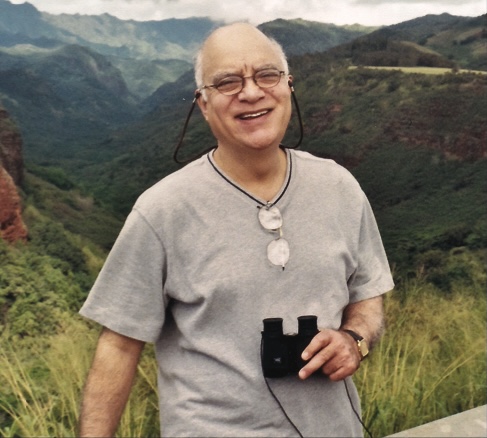

In 1987, at age 42, my father, Suneil Kumar Gurwara, was diagnosed with brain cancer. In the years that followed, he had four surgeries, radiation and chemotherapy and was permanently on anti-seizure medication. He retired within a few years of his diagnosis due to his disabilities, which included aphasia, fatigue, nausea, double vision and imbalance. All through those years, his days were filled with hospital stays, MRIs, doctor visits, constant adjustments to his medication and managing the effects of all his medication and brain injury.

Finally, in 2005, he was diagnosed as terminal and given four to six weeks to live. From that time until his death, we endured an exhausting run of care at home, minimal privacy in our home with our supportive extended family staying with us, hospice care-workers, visitors and phone calls, while neglecting our regular duties. Amidst all this frenzy was the desire to freeze or go back in time to better days. Very quickly it was clear that a chronically ill dad had been far more acceptable than a dad who was dying.

AND YET UNPREPARED

Despite death’s inevitability hanging so closely over us for so many years, my mother and I were still unprepared and caught off guard when my father’s final diagnosis was given. Due to the effort to help him stay healthy over the years, we should have been emotionally prepared, and not surprised, when the end became imminent. And despite the years that his body had sustained the disease, his health unraveled relatively quickly at the end, much more quickly than we had expected.

An old story helps illustrate the incongruity between helping a loved one overcome a life-threatening disease or situation yet still being unprepared emotionally and not accepting the end when it arrives. One day, a young father returned home after being away at work. His wife sadly greeted him and asked, “If I had borrowed a piece of beautiful jewelry from a friend and that friend came to claim it back, would you tell me to keep it?” “Of course not,” her husband replied. “It doesn’t belong to us. You must return it.” “Then you must think the same of your child,” his wife responded, referring to their dear son, who just succumbed to an injury from an accident.

The father’s perspective based on his reply to his wife in this story is logical–we cannot keep what is not ours and should not be attached to it. But most of us slip out of this perspective when a loved one is involved and the unalterable, final decree has been handed to us. We cling and protest that there was not enough time. We feel lonely and left behind. We forget the wisdom behind the traditional Hindi expression used to communicate that someone has died, “Poore ho gayein.” “The person has become complete.”

KRISHNA’S ADVICE

Swami Brahmarupananda of the Vedanta Center of Greater Washington DC, emphasises having an “exit strategy” in life and points to the Bhagavad Gita for instruction. In Chapter Eight, in the final two lines of verse two, Arjuna asks Lord Krishna,”How are you to be known at the time of departure?” Krishna replies, “If a person remembers Me, he will reach Me.”

If we practice constant recollection of God and perform all our duties as an offering to God, there is a high probability we will remember God at the time of our death. In other words, Swami Bhramarupananda explains, we are working to ensure a bright future.

My father received his final diagnosis in the hospital and was discharged to receive hospice care at home. While he was highly symptomatic of his disease, his essential self and most of his mental faculties were still intact for the first couple weeks. He remained polite and kind to all the caregivers who helped him, did not decline anybody the opportunity to meet him for a final time and graciously accepted help and care from family members. At our request, a spiritual guide came to our home to provide my father some guidance and the opportunity to share. She asked him, “Suneilji, do you have any fears about the future?” My gurdwara-raised father responded simply, “Satnam sri whaeguru,” which my mother translates as, “Hail to the all-pervading Supreme Reality whose true name eliminates spiritual darkness.” Though my father was saying goodbye to so many, and his body was rapidly deteriorating, he was striving constantly to keep his mind focused where it needed to be.

ACCEPTING THE INEVITABLE

When a person is in his final weeks, days and hours, how can his family maintain an atmosphere that supports his efforts to keep his energy focused on the Divine?

When the neurologist straightforwardly but compassionately told my father, mother and me that the brain cancer had become uncontrollable, my father appeared to understand and accept. “Final stop,” he said. Importantly for my father, my mother and I also accepted that diagnosis. We did not try to beat it or convince him to try one more option or see another doctor. We knew we must accept that it was time to move to the next stage. We strived for equanimity, to be comfortable and at peace.

My father’s extended illness had given us many, many opportunities to reflect and work toward that mind set. When the time to prepare is short, achieving such equanimity can be much harder. One may still try to fight the illness or injury or get a third, fourth or fifth diagnosis. Some even become angry at the patient and at the disease: “How could you let this happen?”or “We’ll fight this thing and bring you out on top.”

However, in order to open the door and walk through to the next stage, the patient requires spiritual support. Making it known that you are there to help him through that door and not pull him back will make his preparations and transition more peaceful.

In an article titled, “Why Doctors Die Differently,” Dr. Ken Murray points out that, unlike the patients they treat, doctors tend to refuse life extending measures for themselves, despite their extensive knowledge of treatment options. Their careers have taught them the limits of treatment and the essential futility of many modern life-extending measures. Their career is, in effect, a life-long meditation on such issues. They understand and accept the need to plan for the end. Denial of the inevitable is not a line of thinking for doctors, says Murray, so most opt for a graceful exit.

It is a critical time, when a terminal diagnosis has been given. If unable to let go, both the patient and accompanying family members become volatile and angry if encouraged to stop treatment and concentrate on a comfortable departure. Patient and family must be able to cut through the distractions of pinpointing causes and grasping at options. Of course, that mind set evolves over time and from within. Doctors are reminded daily of death’s certainty. We, too, should reflect on the inevitable outcome of life and achieve equanimity about it now.

VISITS FROM FRIENDS AND FAMILY

Family from out of town came to stay with us and provide support and help, physically and emotionally. Friends also came to visit and say goodbye to my father. On some days we had many visitors, which we soon found could dramatically detract from the peaceful environment we were trying to cultivate.

Jacqueline Krock, a hospice nurse in Naperville, Illinois, recalls a patient who made a list of all the people with whom she wanted to visit before she died. Mrs. Krock wryly points out, “If you weren’t on her list, too bad. She didn’t have the time.” Many people, Mrs. Krock says, desire to visit with a dying person for an essentially selfish purpose. They may want a connection, they may want to alleviate guilt, or they may simply feel obliged and want to avoid feeling neglectful. Mrs. Krock suggests having a “gatekeeper” who is not emotionally attached to the patient to manage traffic and politely keep certain visitors away, guiding them to help in other ways, such as doing an errand or chore for the family.

AFTER THE END

In the months following the transition, my family and I gradually established a new normalcy. Caring for a dying patient and going through the last rites is a time of high activity, distracting everyone from what is often the more difficult stage called “after,” the large vacuum that used to be filled with giving care.

Swami Brahmarupananda states that Vedanta prepares us for this inevitable journey as no other knowledge does. Just as you work to help your loved one prepare for a bright future, ensure the same for yourself by remembering Krishna’s instructions: as much as possible, practice constant, unbroken recollection of the Divine and do your duties as an offering to the Divine. The mother in the story reminded her husband that their son was like a jewel borrowed from the Divine. We can keep this in mind when preparing for a loved one’s end of life and in continuing on with our own remaining time.

Sonia Sweet Kumar (soniasweetkumar _@_ gmail.com) lives in Naperville, Illinois, with her husband, Brendan Fitzpatrick, and their three children, Rajkumar, Simran and Avinash. She has a master’s degree in communication from DePaul University.