BY SATGURU SIVAYA SUBRAMUNIYASWAMI

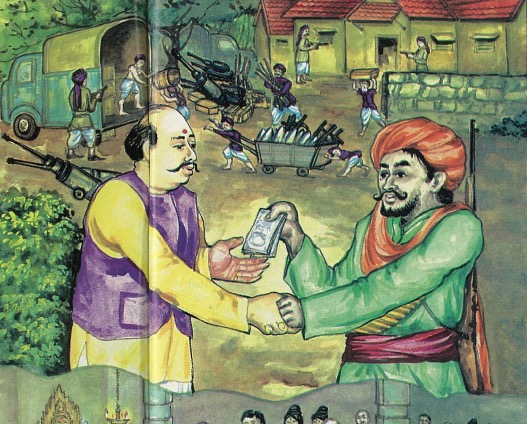

My satguru, the venerable Sage Yogaswami, discriminated between good money and bad money and taught us all this lesson. Money coming from dharma’s honest labor was precious to him to receive, and he used it wisely in promoting the mission of the mission of his lineage. Money coming from adharmic attainments was distasteful to him. He warned that such gifts would, when spent, bring the demons from the Narakaloka into the sanctum sanctorum of our shrines to create havoc in the minds of devotees. This has been the unsought-for reward for receiving bad money–funds gained through ill-gotten means–for many ashrams this century. One day a rich merchant came to Yogaswami’s hut with a big silver tray piled with gold coins and other wealth. Yogaswami, knowing the man made his money in wrongful ways, kicked the tray on the ground and sent the man away.

Yes, there is such a thing as good and bad money, because, after all, money is energy. Why is money energy? Money gives energy. Money is power. Money is a form of prana captured in paper, in silver and most importantly in gold. Actually, gold is real money, the basis of all paper money, coinage, checks and bank drafts. All the money in the world fluctuates in value according to the price of gold, as far as I know. And, mystically, if you have gold in your home or your corporation–I mean real gold–your real wealth will increase according to the quantity of gold that you have.

Good money is righteous money, funds derived from a righteous source, earned by helping people, not hurting people, serving people, not cheating them, making people happy, fulfilling their needs. This is righteous money. Righteous money does good things. When spent or invested, it yields right results that are long lasting and will always give fruit and many seeds to grow with its interest and dividends from the capital gains.

On the contrary, bad money does bad things–money earned through selling arms, drugs, taking bribes, manipulating divorce, performing abortions, gambling, fraud, theft–money gained through a hundred dark and devious ways. Bad money issues from a bad intent which precedes a wrongdoing for gain or profit. That is bad money. When spent or invested, it can be expected to bring unexpected negative consequences. Good money is suitable for building temples and other institutions that do good for people. Bad money is sometimes gifted to build temples or other social institutions, but often only to ease the conscience of the person who committed sins to gain the money. Nothing good will come of it. The institution will fail. The temple will be a museum, its darshan nil; its shakti, though expected to be present, will be nonexistent. Bad money provokes bad acts which are long lasting, and it sours good acts within a short span of time within the lives of the people who receive it.

In 1991 I composed an aphorism to guide those who have sought my opinion on this matter. It says, “All seekers of truth know bad money can never do good deeds and refuse soiled funds from any source. Nor can good money used wrongly reap right results. Ill-gotten money is never well-spent, but has a curse upon it. Aum.”

Some postulate that using bad money for good purposes purifies it. That is a very unknowledgable and improper concept, because prana, which is money, cannot be transformed so frivolously. Many among this group of misguided or naive individuals have lived to witness their own destruction through the use of tainted wealth. Also, we come into the illegality of laundering money. Money cannot be laundered by religious institutions. Money cannot be legally laundered by banks. Money cannot be laundered by individuals. Further, we know that those who give ill-gotten bounty money to a religious institution will subtly but aggressively seek to infiltrate, dilute and eventually control the entire facility, including the swami, his monastic staff, members and students. If bad money is accepted, it will bring an avalanche of adharma leading to the dissolution of the fellowships that have succumbed, after which a new cycle would have to begin, of building back their fundamental policies to dharma once again.

My own satguru set a noble example of living simply, only overnighting in the homes of disciples who live up to their vows and only accepting good money. He knew that accepting bad money brings in the asuras and binds the receiver, the ashram or institution to the external world in a web of obligations. How does one know if he has received bad money? When feelings of psychological obligation to the giver arise. This feeling does not arise after good money is given freely for God’s work. Bad money is given with strings and guilt attached.

Our message to religious institutions, ashrams and colleges is: don’t take bad money. Look for good, or white, money–known in Sanskrit as shukladana. Reject bad, or black, money–called krishnadana. If you don’t know where the money came from, then tactfully find out in some way. How does the donor earn his living? Did the money come from performing abortions, gambling, accepting bribes, adharmic practices of law or shady business dealings? Is it being given to ease the conscience?

Even today’s election candidates examine the source of donations exceeding $10,000 or more–investigating into how the person lives and how the money was gotten–then either receive the gift wholeheartedly or turn it back. When the source is secret, the source of gain is suspect. When the source is freely divulged, it is freed from such apprehension. In the Devaloka, there are devas, angels, who monitor carefully, 24-hours a day, the sources of gain leading to wealth, because the pranic bonds are heavy for the wrongdoer and his accomplices.

Imagine, for instance, an arms seller who buys his merchandise surreptitiously and then sells it secretly or in a store–shotguns and pistols, machine guns, grenades and missles–instruments of torture and death. Money from this enterprise invested in a religious institution or educational institution or anything that is doing good for people will eventually turn that institution sour, just like putting vinegar into milk.

The spiritual leader’s duty is to turn his or her back to such a panderer of bad money and show him the door, just as an honest politician would turn back election donations coming from a subversive source, gained by hurtful practices, lest he suffer the censure of his constituancy at a later time, which he hopes to avoid to hold his office. A politician has to protect his reputation. The spiritual leader will intuitively refuse bad money. He doesn’t need money. When money comes, he does things. If it doesn’t come, he also does things but in a different way.

In Reno, Nevada, for many years the gambling casinos gave college scholarships to students at high schools. Then there came a time of conscience among educators when they could no longer accept these scholarships earned from the sin of gambling to send children forward into higher studies. They did not feel in their heart, mind and soul that it was right. Drawing from their example, we extend the boundaries of religion to education and to the human conscience of right conduct on this Earth.

Humans haven’t changed that much. Over 2,000 years ago, Saint Tiruvalluvar wrote in his Holy Kural, perhaps the world’s greatest ethical scripture, sworn on in Indian courts of law in Tamil Nadu:

The worst poverty of worthy men is more worthwhile than the wildest wealth amassed in wicked ways (657).

What is gained by tears will go by tears. Though it begins with loss, in the end goodness gives many good things (659).

Protecting the country by wrongly garnered wealth is like preserving water in an unbaked pot of clay (660).

Riches acquired by mindful means, in a manner that harms no one, will bring both piety and pleasure (verse 754).

Wealth acquired without compassion and loveis to be eschewed, not embraced (verse 755).

A fortune amassed by fraud may appear to prosper but all too soon perish altogether (verse 283).

Finding delight in defrauding others yields the fruit of undying suffering when those delights ripen (verse 284).