By Prabha Prabhakar Bhardwaj

Many magical tales are told about Gangotri, the mythical wellspring of the Ganges, India’s most famous sacred river. I’ve just returned from this wondrous place and would like to share my experience of it. First, a story.

There was once a handsome prince who wanted a Goddess named Ganga to come to Earth and bless him. For 5,500 years he meditated and prayed constantly for this to occur. Finally, the Goddess consented to appease him, but said She had a provision. She would come to earth only if She might gain some assistance in the endeavor from Her dear friend, Lord Siva. After all, She surmised, it was sure to be a somewhat dramatic if not dangerous landing. Earth, She was certain, would not be able to sustain the full force of Her unobstructed descent. Lord Siva, of course, consented, and all pertinent arrangements were made. At an astrologically appropriate time agreed upon by all of the Gods, Ganga leapt from heaven as a giant torrent of water and fell head first into the vast net of Siva’s sprawling, golden red locks. And as She landed with a thundering crash, She dispersed Herself in all directions. First, She became the holy Ganges river. Then She streamed forth many of India’s other holy tributaries. This is one of the many stories told about Gangotri, the alleged source of the Ganges. But there is more to this story than the fable. Gangotri, as it turns out, is not the real source at all.

From Source to Source: Gangotri, which literally means “Ganges flowing North,” is situated 10,500 feet above sea level in a region of India called Garhwal. This is said to be the geographical location of the river’s glacial origin during the time of the Vedas. The GangotriGlacier, as it has come to be known, has receded ten miles back and up into the mountains to a place called Gomukh. Although markings of the original positioning of the glacier are still quite visible at Gangotri, the glacier itself cannot be seen at all. Gomukh, which literally means “cow’s face,” is now the true source of the holy Ganges.

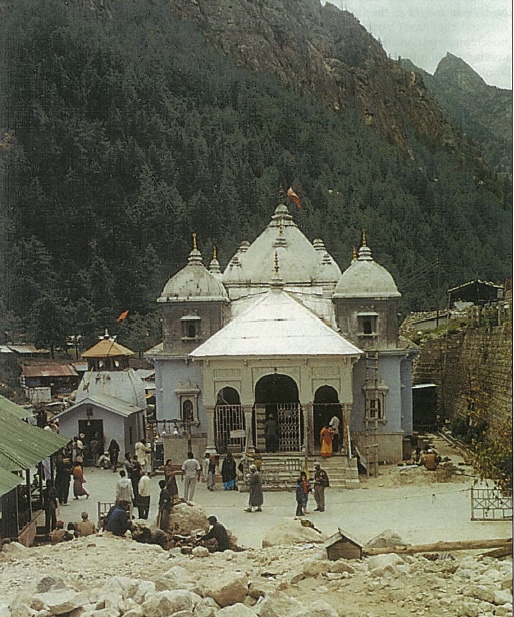

Nevertheless, the Gangotri Temple remains an important pilgrimage destination. Due to weather constraints, it is open to the public only about half the year, from the end of April until Dipavali in October. When the temple closes it is indeed a grand affair. Special rituals are conducted as the shrine of Goddess Ganga is elaborately moved to a place called Mukhba for the winter months. This ceremonial transport of the Deity is undertaken with great religious fervor.

A difficult trek: The journey on to Gomukh from Gangotri requires tremendous physical endurance and mental fortitude. Only the most enthusiastic pilgrims are able to contend with the challenges that arise almost immediately. The rigorous odyssey starts with a Herculean trudge straight up the mountain behind the Gangotri temple, heading directly for what seems like nothing but snow-capped Himalayan mountain peaks. There are no marked paths or trails, and many portions of the puzzle-like distance to be traversed are fraught with truly dangerous obstacles, like sheer rock cliffs and deep ravines. Pilgrims must be prepared to cross icy streams with hazardous currents and scale rough rocky terrain, sometimes grappling up almost vertical inclines. Along the way are Chirbasa and Bhojbasa, two other important but lesser known pilgrimage spots. En route are spectacular panoramic forests with rare trees, like the Bhojpatra, famous for its bark used in ancient times as writing paper for scripture.

At 14,000 feet above sea level, Gomukh rests securely in the shadow of a mountain called Shivling Peak, which stands authoritatively behind and above it like an invincible temple guard. Shivling’s 350-foot frontal face, a sheer cliff of treacherous icy rock, has never been climbed and towers 21,470 feet above sea level. The basin below is at 16,404 feet elevation and spreads back six miles to the true source of the Ganges, a cave beneath the glacier. In the background, three peaks of the Chaukhamba mountain range hover wondrously. Strewn all about are huge avalanched boulders, like the play toys of giants. The whole area is untouched by human exploitation. There are no commercial activities of any kind no food, tea or flowers are sold. Everything here is natural, untouched and unchanged, perhaps much as it was in Vedic times.

Some noble pilgrims of the past have lost their lives during this particularly difficult pilgrimage due to landslides, heavy rains or sudden temperature drops. Yet, today pilgrims keep coming, fascinated and ardent beyond their fear of death, infatuated by the irresistible allure of God. Here, serenity and total silence prevail. There is a holy presence. No one who has braved the elements for the blessings of Gomukh could possibly doubt that Goddess Ganga lives here and is, indeed, Divine.

Although many assume that the Ganges will flow forever, the fact that its glacial source is receding at a signifigant rate is hard to ignore. Undeniable evidence shows that ten of its sixteen original miles of ground coverage have dissappeared. This is difficult to place in a specific time frame. However, if it is true that it was full size during ÒVedic times”, and we estimate that to ne 6000BCE,a common traditionally acknowledged calculation for the earliest Vedic rendering, we could make a reasonable assumption that, having receded 10 miles in 8000 years, it might be that in 7000 years Goddess Ganga will have to come to Earth once again.