Assam continues to amaze in this second part of our report as we explore the religious centers, called satras, founded by the 16th-century Vaishnava saint Sankardev, the great temples of the Ahom kings and the educational projects of a wide range of Hindu institutions striving to meet the state’s modern challenges.

By Rajiv Malik, New Delhi

Last issue we explored guwahati and environs in western Assam, which include both Kamakhya, the state’s most famous Goddess temple, and the birthplace in Nagaon of Srimant Sankardev (1449-1568), Assam’s most influential saint. Along the way, photographer Thomas Kelly and I met with the Bodo tribal community, visited both a Brahma Samaj and a Bathou temple and spoke with leaders of several organizations engaged in education and social upliftment. The state’s immense diversity was immediately evident.

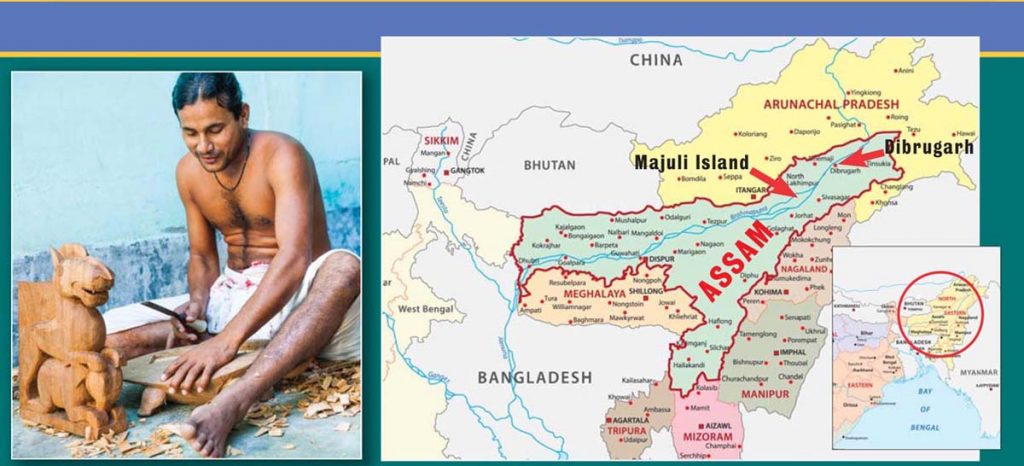

The second part of our adventure, reported here, takes us east and up the mighty Brahmaputra River to Dibrugarh, center of the tea country, and from there to Majuli Island, where Sankardev established the great satra centers of Ekasarana Dharma. As around Guwahati, we visited famed places of worship, including Tilinga (the “bell temple”) and the 18th-century Sivadol Temple built by the Ahom kings at Shiv Sagar. We met with the tea garden workers whose ancestors were brought by the British from different parts of India as indentured laborers, and with the native Assamese people and tribes, some of whom arrived thousands of years ago. We learned of modern issues, such as the large-scale migration of Bangladeshis into the state, which is impacting its demography with possibly disastrous consequences in the future. Finally, we were impressed with the serious work of a number of Hindu organizations who are developing basic educational institutions in the most remote villages as well as elite schools in the city which challenge even those of the Christian missionaries.

Majuli Island

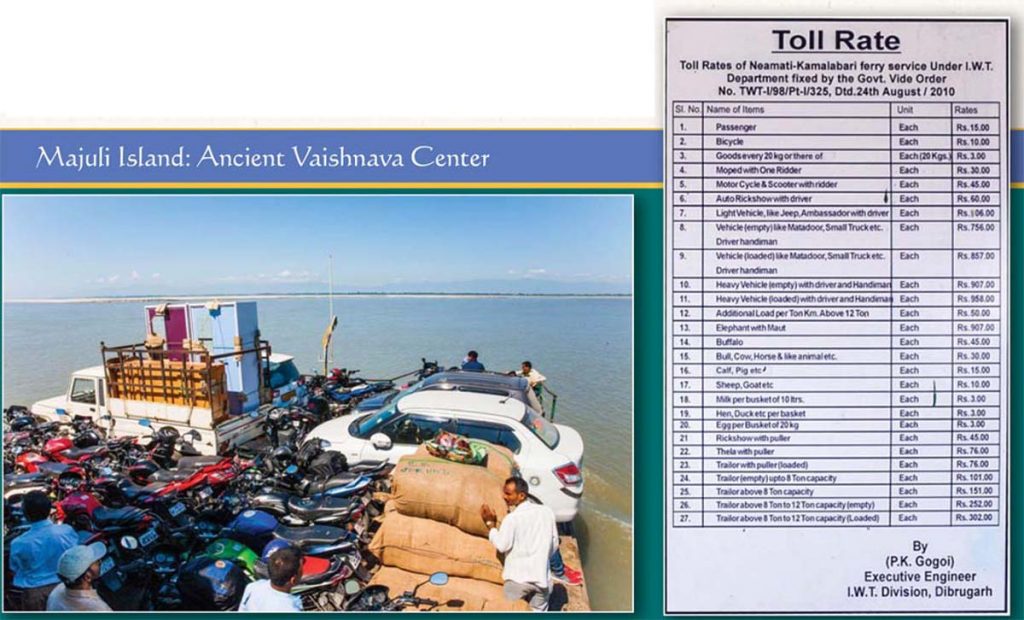

Everyone we consulted about our trip urged us to go to Majuli Island, telling us we would never understand Assam without a visit to this storehouse of art and culture that was once a center of Assamese civilization. Majuli is where Sankardev met Madhavdeva, who became his chief disciple and was instrumental in the spread of Ekanatha Dharma. It is now rather out of the way, requiring ferry service to reach it, across the Brahmaputra river and having minimalist accommodations for visitors.

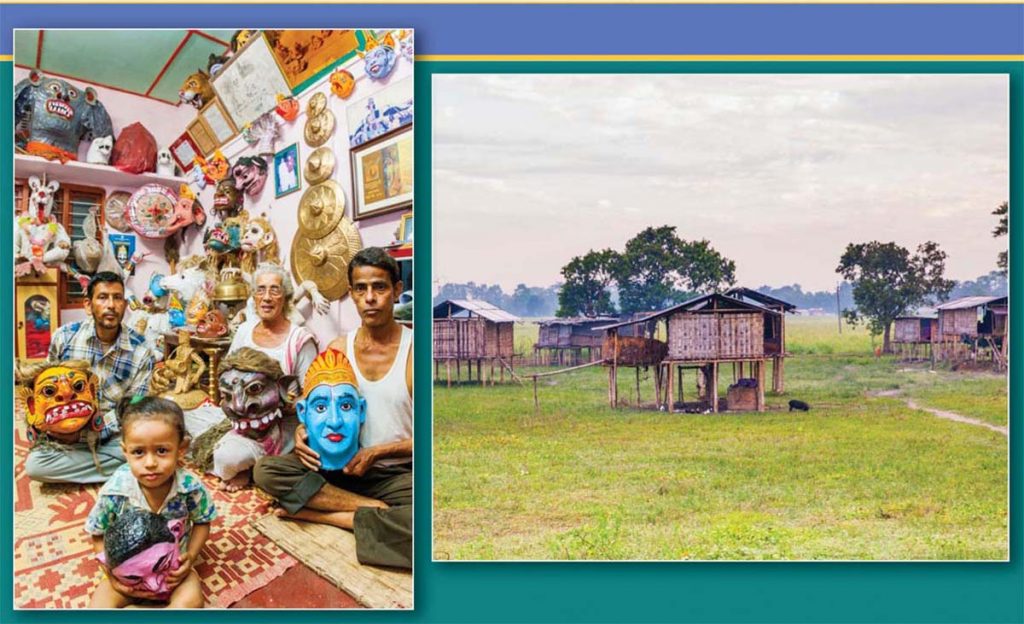

When Sankardev established the many satras (religious/cultural centers) here in the 16th century, the area was not an island. It was a peninsula between the Brahmaputra and another river. In a catastrophic flood lasting 15 days in 1750—one still mentioned prominently in local folklore—the Brahmaputra broke its banks and captured the adjacent river channel, turning the peninsula into an island. Majuli has been eroding at an increasing rate ever since, going from 483 square miles in 1900 to just 136 in 2014.

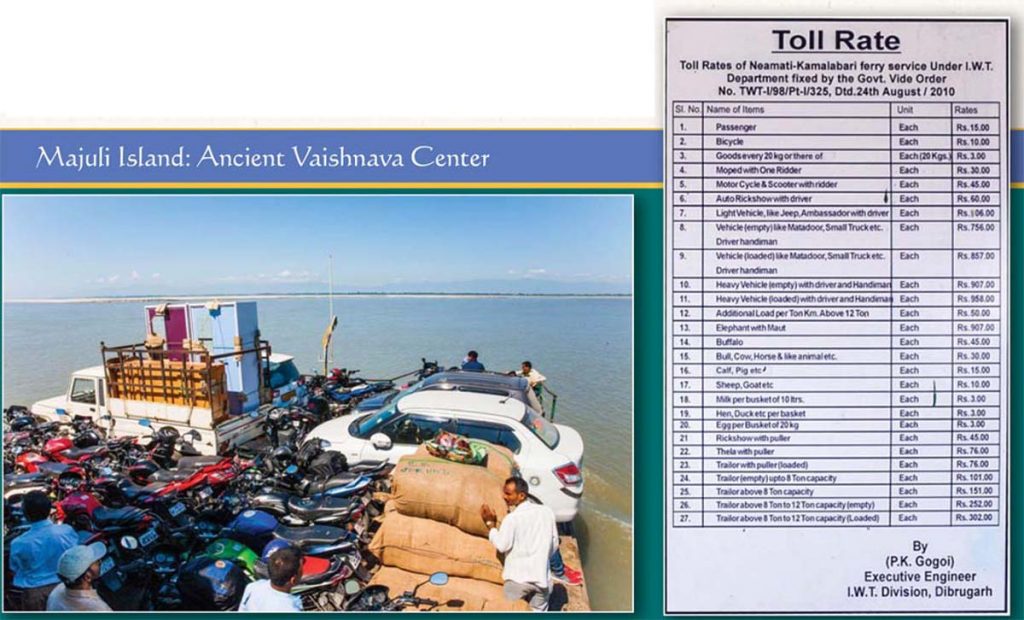

One travels there today by ferryboats that regularly depart from Nemati Ghat, 170 kms downstream from Dibrugarh. Everything gets to the island by ferry, a fact of life reflected in the tariff posted by our ferry’s wheelhouse. With occasionally creative spelling, it lists toll rates for all manner of creatures and cargo from people (us$0.23) and “ducks by the basket” ($0.05), to a heavy truck ($14.72), and an elephant with mahout ($13.94).

Uttar Kamalabari

After an hour-and-a-half ride across the turbulent river, Thomas, guide Ramesh Limbo and I are back in our cab and headed for Uttar Kamalabari Satra, one of the island’s most famous religious centers of the Ekanatha Dharma, and first of three we will visit. Lush green farms and beautiful stands of bamboo line both sides of the road. Peace and spirituality permeate the unpolluted environment. As we approach the satra’s grand entrance, we see a huge billboard announcing the popular Raas Leela programs scheduled for November. Pilgrims and tourists flock here for the celebration from Assam itself, the rest of India and even overseas.

Uttar Kamalabari Satra is a center for art, with artists trained here in classical sattriya music and dance developed by Sankardev himself. A brahmachari we meet on our way in (whom we take to be a kitchen worker, as he is spreading out rice to dry) is himself an accomplished dancer who has performed in many parts of the world. This satra has some 400,000 devotees across Assam and in other parts of India.

The satra’s head, Satradhikari Janardan Goswami, grants us a long interview. It was here, Janardan explains, that Sankardev started the tradition of naam ghar (“prayer house”), such as the one we visited earlier at Batadrava, Sankardev’s birthplace. As mentioned in the last issue, naam ghars are temples with no enshrined Deity in which devotees chant the names of Krishna before a seven-tiered throne which holds only the Bhagavat Purana. This is a central practice of the Ekasarana Dharma (“shelter-in-one religion”) founded by Sankardev. Each satra includes a naam ghar as well as other facilities.

The satras founded by Sankardev, a householder, are run by family men. The six begun by Madhavdeva, a bachelor, are run by brahmacharis; these are called udasin satras. Of the island’s original 64 satras, only 37 remain active. In the whole of Assam, there are 23 udasin satras (including this one), staffed by 800 brahmacharis, and 900 satras run by householders. “The householder satras are more in number because the households give birth to children who start their own,” Janardan explains. There are, we are told, ten thousand naam ghar temples in Assam.

A small child joins us during the interview, playing with Janardan’s mobile phone and being handled with a lot of love and affection. We learn that a householder attached to the satra offered this child, his son, to the satra as he saw him as a future monk. Once brought to the satra, the boy refused to return with his parents; and even now has no interest in seeing them.

Of the satra’s 100 bramachari, most were given by the parents around the age of six. “It is not compulsory they remain brahmacharis; they can later opt for the householder life at an appropriate stage and time and serve the satra in that way,” Janardan explained. The children attend both the satra’s gurukulam and government school. “We place a lot of emphasis on good quality education.”

Janardan explained at length about the activities of Sankardev; and as he lived 120 years, the saint’s story is long indeed! Sankardev worked among the many castes and tribes of Assam and initiated saints from all communities in an effort to bring them all under the umbrella of Vaishnava Hinduism. “The main difference between Majuli and other centers of Vaishnavism is that we worship only Lord Krishna, while they worship both Radha and Krishna,” Janardan told us.

“Earlier,” he said, “the satras focused mainly on religious activities and the promotion of art and culture. Now they are taking up social work, including education and medicine.” He himself travels regularly to visit the naam ghars in various villages. His brahmacharis, one hundred in number, perform kirtan and bhajan but do not perform priestly functions such as puja, yagna, samskaras or marriage ceremonies.

Janardan said he is pleased with the work of Ekal Vidyalaya, which has 210 schools on Majuli, some in remote areas lacking even government schools. Ekal has been effective, he told us, in countering the influence of the Christian missionaries among the tribals.

He advised, “If we want our youth to become spiritual, then the parents must follow the path of spirituality as well. Today the problem is that the parents do not, and therefore are not at peace with themselves. Once they connect to the spiritual lifestyle, they will become blissful and peaceful, and the youth will be inspired to follow. Then there will be real change in society.”

Like all satras, Uttar Kamalabari has a large hall where its monks perform their daily prayers, bhajan, kirtans and rituals. The hall here is full of spiritual vibrations though no activity is taking place there when we visit. On all the four sides of the naam ghar are rows of rooms, about twelve feet on a side, sleeping quarters for the monks, including the monastery head. This is a common pattern for the satras.

A Mising Voice

Departing Majuli on the ferryboat, we meet Mising tribe member Raju Gam, 28. Numbering one million in Assam—Misings are the second largest tribal group in the northeast, after the Bodos, also of Assam. Raju is a graduate in agricultural studies who works for Amar Majuli, an NGO engaged in the empowerment of women and focusing on organic agriculture and youth leadership.

There are five opeems, or clans, among the Mising: Mayang, Bagra, Delu, Ayong and Sayung. Their traditional practices are the same, and they are equal to each other, with no caste hierarchy. I consider myself a Hindu, as do many others in the Mising tribe. We worship Lord Krishna as our chief Deity.

We marry outside our own clan, that is, into one of the other four groups. If the marriage is arranged, 101 betel nuts are presented to the bride’s father and her family by the groom’s side. This offering is symbolic and considered equivalent to a gift of 100,000 rupees. After this, the bride and her family are brought to the groom’s house, where they are offered rice wine, apong, as part of the marriage ceremony. Having wine is part of our rituals, but drinking to extreme is rare among our people. Earlier, marriage took place around 17; now, with education and better employment, the age is going up. Previously the focus was on the number of children; now it is on their education. Literacy is today 50 percent among the Mising. Love marriages, such as my own, which my family has accepted, are becoming common.

The positive thing about the satras is that they help educate the poor children through supporting the Ekal movement. They also contribute to the local economy and its development by attracting tourists and pilgrims. However, when it comes to the people of the Mising community, we are not so welcome in the satras because we are taken as meat eaters and consume liquor. Because of this attitude of the satras toward the community, some of our people are attracted to Christianity, as they do not discriminate against us for the reasons the satras do. The missionaries help us in our education and do it without insisting we convert or interfering in our religious practices. Those who do convert do so out of their own willingness.

Most boys living in the satras are from a low economic background. At the satras they get a good education, and when they grow up they are free to become householders. However, the children of the Mising community are not given the same opportunity, despite our aspiration to do so. Consider my own case. Though I am a vegetarian, no satra will allow me to stay with them and be educated utilizing their facilities inside their campus. The same is true for all other children from the Mising community. The satras will also not entertain people who in any way question their authority.

It is unfortunate that people dump garbage in the Brahmaputra River. We Mising tribals would never pollute the river, whom we call Brahmaputra Baba and treat as a God. Now the river is shrinking, and we are quite worried about it.

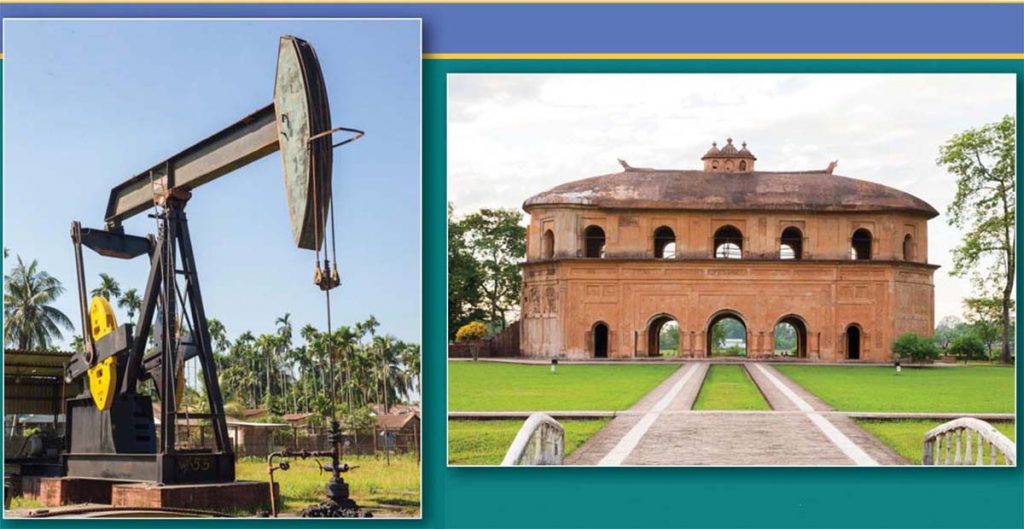

Auniati Satra

We arrive at Majuli’s second-largest satra, Auniati, to find the head, Dr. Pitambar Dev Goswami, deeply engaged in arranging their next raas leela dance and drama performance. But when he learns we are from Hinduism Today—which he has been reading for years—he is delighted to meet us. He compliments our work, saying, “I am happy that the magazine is run by a group of Saivite saints, and that it gives coverage to other Hindu communities, including Vaishnavites.”

This is another brahmachari satra, with four hundred in residence. As at Uttar Kamalabari, the boys are trained here from a young age and can opt later to enter householder life if they choose. The focus is on music, drama, dance, bhajan and kirtan, as promoted by Sankardev to foster harmonious coexistence. The residents specialize in several forms of service, including leading kirtan and bhajan, playing musical instruments, such as the dholak drum, and teaching.

A satra, according to Dr. Pitambar Goswami, is a place where resides Guru, Dev (God), Naam (chanting of God’s name) and Bhagat (devotee). “At other holy places, these four things come together only at particular times, but in our satras they are continuously present.”

This satra’s main following are the tribal people of Majuli—500,000 from the Sonwal Kachari tribe alone, as well as a large number from the Mising and Deori tribes. Many Mising tribals, Dr. Pitambar reports, have converted to Christianity. The satra’s efforts have succeeded so far only in reconverting two or three percent, but he feels their work is gaining momentum. He praises pollution-free Majuli Island as a “very pure and spiritual place” and urges us to return for at least a month on our next visit.

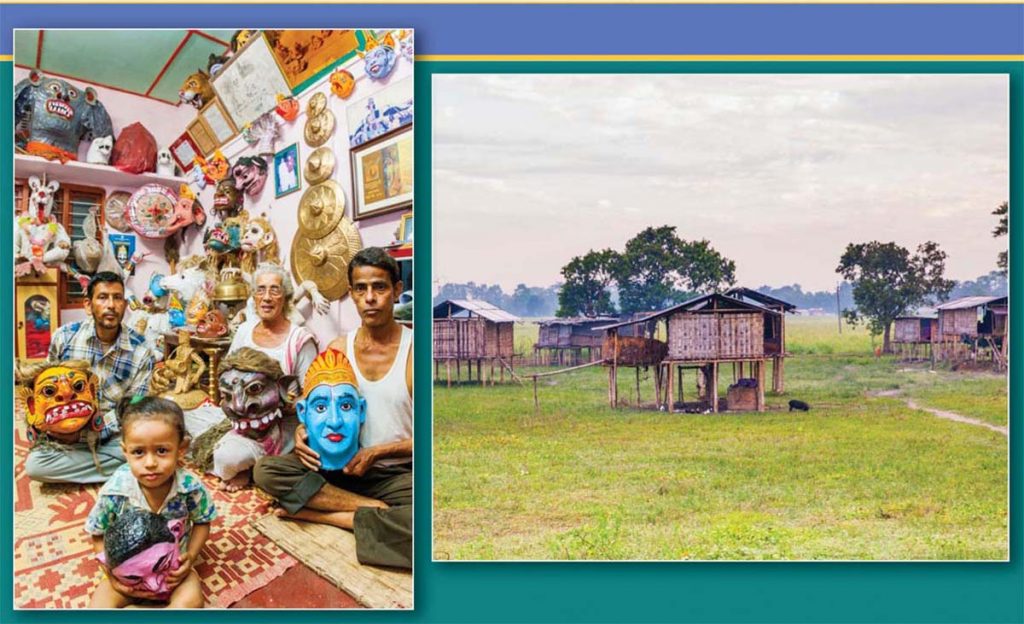

The Mask Makers

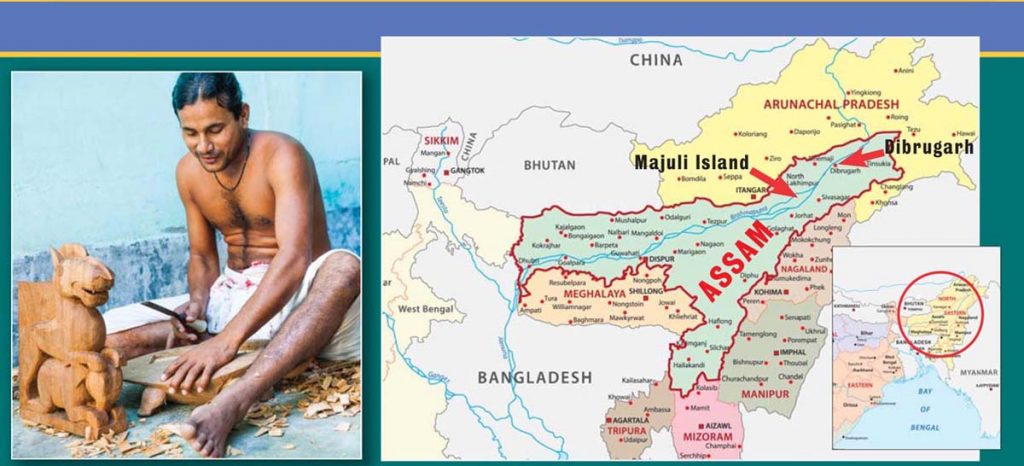

Our third stop, Chamguri Satra, is famous for its mask making and the home of the nationally recognized artist, Koshakanta Dev Goswami. His big drawing room is full of masks of varied sizes and different historical characters, mainly belonging to the Mahabharata and Ramayana. Students are regularly sent here by Sangeet Natak Akademi—India’s renowned National Academy for Music, Dance and Drama in Delhi—to learn the intricacies of this unique and colorful art.

Koshakanta is not only an ardent follower of Sankardev, who popularized mask making in Assam, but a direct descendent. He says he is optimistic about the future of the art of mask making, though he wishes the artists were better paid for their work. As he bluntly puts it, “I have received a lot of recognition in my life for my work, but not enough money.” He is happy with the way his four sons are carrying forward his lineage and tradition. One, Pradip, tells us mask making is quite a tedious process, with a single creation sometimes taking weeks to make.

After a night in modest accommodations, we depart Majuli by the morning ferry and return to the river’s eastern side to explore the area’s major temples, starting with the Tilinga.

An Assamese Overview

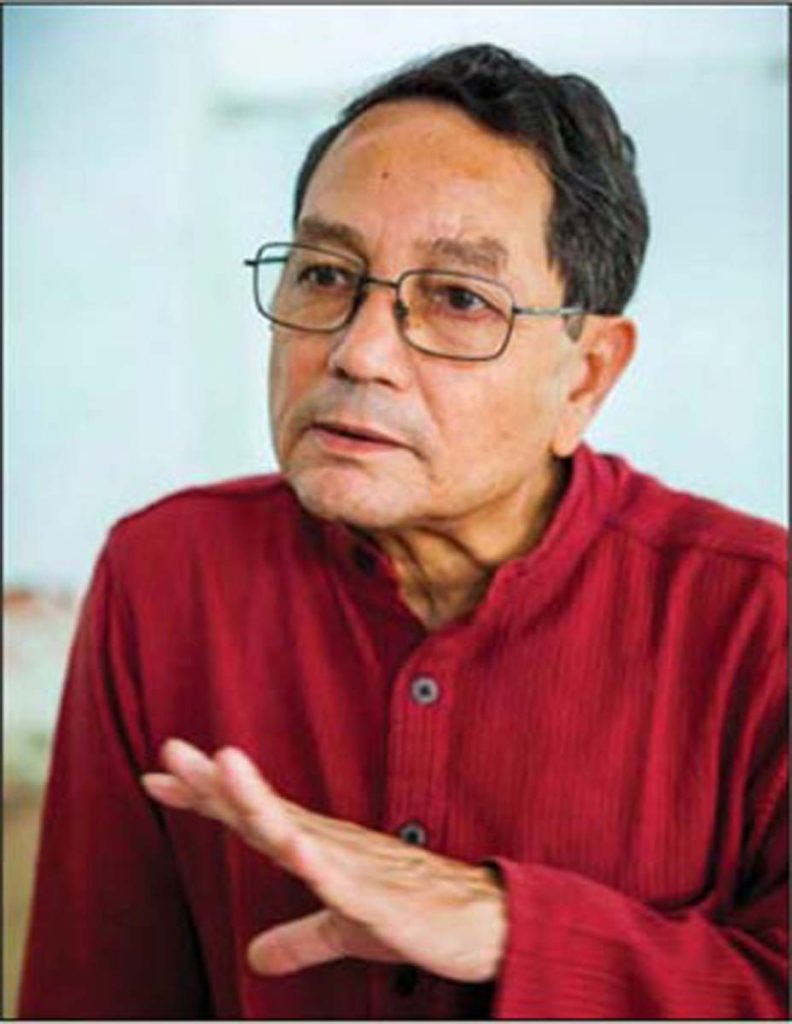

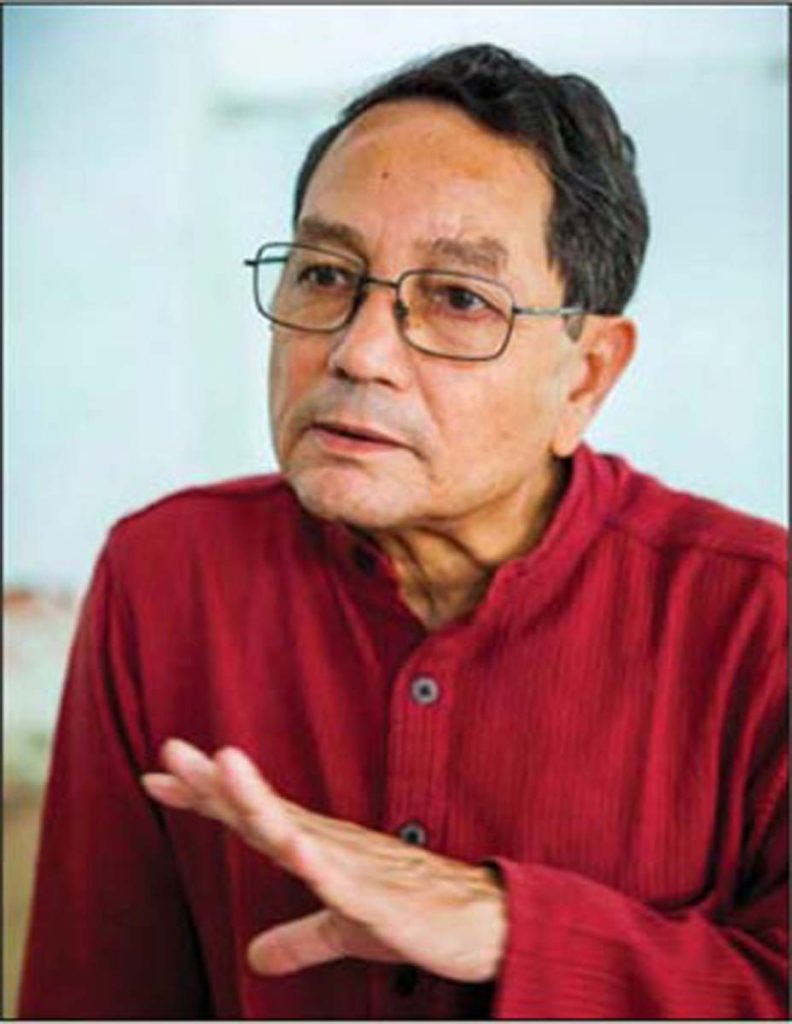

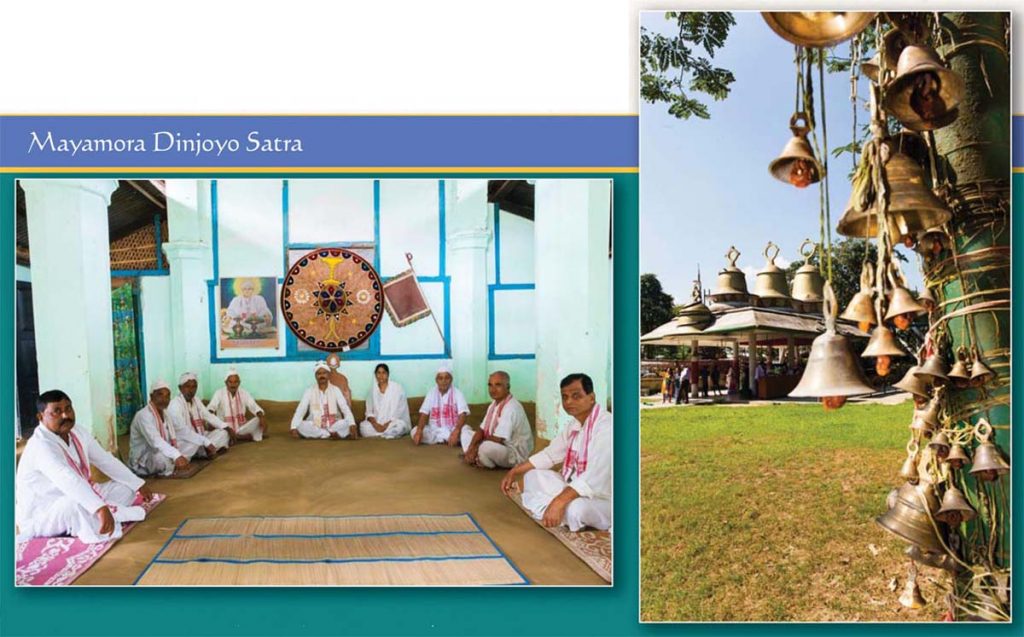

Prof. Dambarudhar Nath holds the Sri Sri Aniruddhadeva Chair in the Department of History of Dibrugarh University. He is the author of Religion and Society in North East India and other books on Assam. He heralds from Majuli and is a disciple of Auniati Satra, which we visited earlier. We interview him at Mayamora Satra, founded by Anirudhadeva (1553-1626) a householder guru in the teaching lineage of Sankardev.

In assam, vaishnavism has four branches, or sanghatis: Brahma, Purush, Nika and Kaal. The first two are grouped under the Sagun Panth and the second under Nirgun Panth. All consider themselves followers of Sankardev in some fashion and all derive their philosophy from the Bhagavat Purana. In the Sagun Panth, bhakti is practiced, and the incarnation of God with attributes is worshiped in the form of a sacred murti or image. Those following Nirgun Panth, which is similar to the philosophy of Sikhism and Kabir, do not worship idols but believe in the principle of Param Brahma [transcendent God]. In Sagun Panth, the caste system is observed, and in Nirgun Panth it is not. Anirudhadeva himself expounded the philosophy of mayamora, literally “illusion kill,” which is part of the Nirgun Panth. It is a kind of advaita view, like that of Adi Shankara, which holds that earthly life is an illusion, and there is no distinction between the Supreme Reality and this world.

This satra was founded in 1601 in Majuli, but shifted here to the eastern side of the Brahmaputra when its original location on the river’s bank eroded away. It is now the main Mayamora satra. In the Mayamora system, the head of the satra may nominate any relative as successor; Anirudhadeva himself appointed his son. The present guru, 90 years old, has appointed a relative who is now effectively the head of this satra. Anirudhadeva believed in a direct relationship with God through bhakti, without seeking any mediator, including priests—an approach that appealed to the tribal and low-caste people of the area, who all joined Anirudhadeva’s movement. This was a political factor in the great civil war of 1769, the Moamoria Rebellion, in which the king was deposed and a follower of this satra succeeded him. The war was so violent it is said half the population of Assam was killed, among them 800,000 followers of this sect.

At the time of Anirudhadev, upper Assam was full of tribals. They were Sanskritized and in a way detribalized, as their tribal culture was eroded by Vaishnava culture. That is the role which Sankardeva and Vaishnavism have played, and that is a great role. Now, although they are disciples they maintain the original culture of drinking, eating meat and moving hither and thither in the jungles. They maintain some part of tribal culture and also maintain their Vaishnava culture. This Mayamora sect has a huge following; almost half of the Vaishnavites of Assam belong to it. It may not have 10,000 naam ghars, but it has a million disciples.

Assam and India

We do not need to look into our connection with India keeping in mind just the 14 km corridor that connects us. India is interwoven and united with Assam. If you think India lives here in its heart, its spirit and spirituality, then this narrow geographical corridor is of little consequence. In the 16th century, Sankardev wrote in praise of India in Bhakti Ratnakar: “Life in India is fruitful. Life in India is to be welcomed. Life in India is to be congratulated. Life in India is meaningful for all human beings. ” He repeats those lines 46 times—this when many people had little sense of India as a whole.

Bangladesh

The Bangladeshi infiltration problem in Assam is very serious. Assam is now full of Bangladeshis. Out of the 30 million population of Assam, around ten million have infiltrated from Bangladesh. The situation is such that you will be afraid of traveling to some parts of Assam. When you visit these places you will feel that you are in Bangladesh and not India. People in the rest of India do not understand the kind of problems we are facing due to Bangladeshis. In some of the places full of Bangladeshis our Hindu population does not even venture out in the marketplace in the evenings, as they are afraid they may be attacked. Human migration is something which is well accepted, but there must be a certain limit.

There is all this talk of Hindu and Muslim Bangladeshi. How can we distinguish between them? A Bangladeshi is a Bangladeshi. He is a foreign national. The problem with foreign nationals is that they do not have any loyalty for our country. They are loyal to another country, not to India. When the country was divided in two parts on the basis of religion, a point was made, and still the impact of that is there in the minds of the people. The people who have formed the government of Assam today are the people who always had the interest of Assam in their mind. So now I trust that they will do good for Assam and not bad for Assam.

Tribals and “Mainstream Hinduism”

Why should the tribals be persuaded to come into “mainstream Hinduism”? This is something problematic. In fact, what the tribals do, they are doing within Hinduism already. I think Hinduism has a lot of variety in it. For example, if you undertake animal sacrifice, you are a Hindu. If you believe in nonviolence, you are a Hindu. If you use the priesthood you are a Hindu; if you perform the rituals yourself, still you are a Hindu. Even if you do not perform rituals, still you are a Hindu. If you bury your dead, you are a Hindu, and if you burn your dead, still you are a Hindu. Are we not varied? The tribals are also following systems of their own and can still be a part of Hindus and Hinduism. We, as Assamese, would like to maintain the plurality to form a better Hindu culture by allowing even the smaller cultures to grow. We do not look down upon any as an inferior religion or “animist;” we treat them as equals. When you have to embrace so many people coming from different backgrounds and you have to make a united India, you will have to see these things in the right perspective.

Youth

It may appear to an outsider sometimes that the tribal youth or our Assamese youth are not much interested in our culture. But if you get to see and participate some of the big religious festivals, like Durga Puja and Sankardev Utsav, Ras Leela, Bhavna, etc., you will realize they very keenly get together to celebrate and organize these events. So, from their Western dress style, which includes jeans and T-shirts, please do not conclude that they do not take interest in their own culture, or that they are going away from spirituality and their own culture. I believe their soul is still connected to their culture.

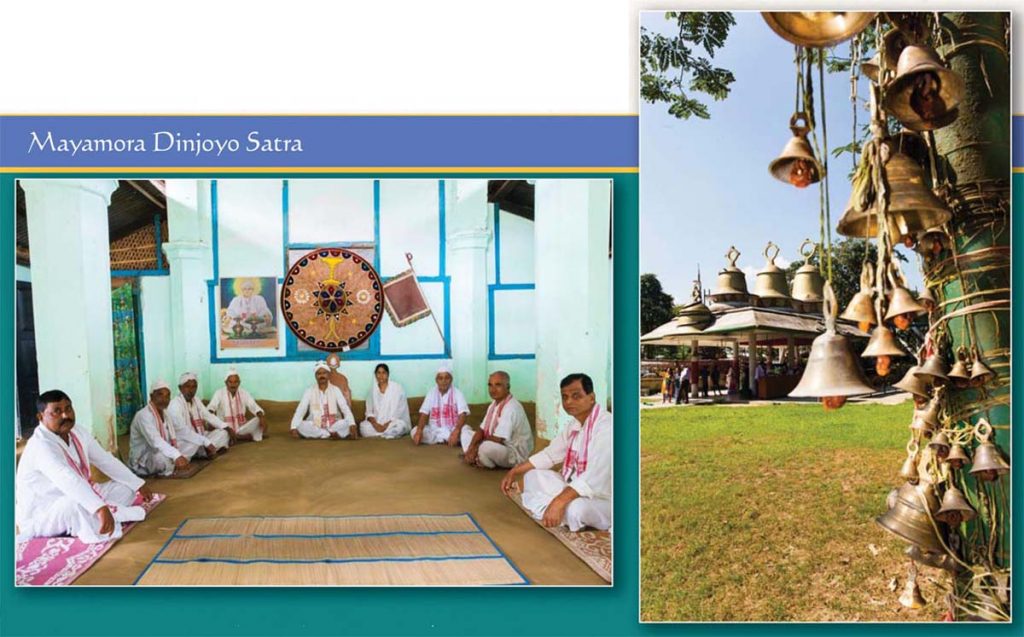

Tinsukia’s Bell Temple

The small but powerful Tilinga or “bell” temple was founded in 1965. The local tea estate workers had discovered a svayambhu (natural, self-manifested) Sivalingam emerging from the ground near a banyan tree. The estate management then built a small Siva temple at the site. No one is precisely sure how the custom of offering bells began, but at some point, a devotee who came to pray at the temple promised to tie a bell to the tree if his prayer was answered. His prayer was answered, and he dutifully came and tied the bell. The news spread, and as more and more people had their prayers fulfilled, the tradition of tying bells to the limbs of this grand old banyan developed. Eventually the tree became unable to support so many bells; so now they are hung on the walls enclosing the temple grounds.

The temple is a full of great energy, life and charm. Priests are available to perform puja for the devotees, and occasionally one will dash outside to the street to bless a new vehicle, a popular service of this temple. But anyone can approach and personally offer worship to the Sivalingam at the base of the banyan with lighted lamps and incense.

After making their prayer, a devotee ties a red sacred thread around one of the temple pillars. Once the prayer is fulfilled, he or she returns to offer a bell. If you are not likely to come back—as in our case—you can tie your bell immediately after making your wish, in anticipation of a positive outcome. Thousands of bells are hung here, each a symbol of hope, aspiration, prayer and gratitude by pilgrims whose prayers were fulfilled.

Outside the temple we witness a procession of more than a hundred devotees of Sankardev walking barefoot along the road. One is carrying Srimad Bhagavad Purana on his head and the others are chanting the name of Lord Krishna. All are dressed in white, with the traditional red-and-white gamcha scarves around their neck. It is a charming demonstration of the remarkable devotion to Sankardev present in Assam.

Offering a Hindu Education

Our first stop after the bell temple is the nearly completed Ekal Abhiyan Gramothan Research Centre. According to Shri Sanjay Trivedi, head of the Van Bandhu Parishad, the center is being established to foster village economic development through improved education, health, medical services and farming techniques. The Parishad already runs 270 Ekal Vidyalayas in the area.

Next is a boys’ hostel run by the Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram, part of their nation-wide program to uplift India’s tribal population. The local leader, Girdhari Parikh, tells us this particular hostel, one of five they operate in Assam, is for children from poor families in the scheduled caste and scheduled tribe communities.

Parikh said once the children complete eighth grade and depart to pursue higher education, the ashram loses contact with them and they may fall under the influence of Christian missionaries. “The missionaries have a very wide network,” he explained, “and their level of work is much bigger than ours. For example, they have orphanages which can accommodate hundreds of Hindu children, and we have no such similar facility. They specifically target the people our society has neglected. But the situation is changing fast because of the Ekal schools.”

He offers his view on a topic we asked several people to comment on: the relationship of the northeast with the rest of India. “It is unfortunate that there is this feeling we are different or there is some kind of a gap between the North Indians and us. The truth is, Assam and the northeast have a special place on the religious map of India. Parasuram, an avatar of Lord Vishnu, is associated with this area, as is Rukmini, wife of Lord Krishna. Bhima and Arjuna of the Mahabharata married girls from here. In fact, Assam is a great pilgrimage destination and should be promoted as such.”

We stopped at the offices of the Shri Hari Satsang Samiti, a wing of the India-wide Ekal Abhiyan or movement. Its head, Madhu Gupta, explains they have 108 speakers, known as Vyas Kathakars, trained in Vrindavan and Ayodhya to narrate Srimad Bhagavat Purana and perform Ram kathas. They do so in two- to three-day events at both large and small venues, mostly in the villages with an Ekal school. The speakers teach the villagers how to perform puja and other simple rituals.

Nepalese Community

Again here we searched out the local Nepalese community, this time in the remote Doom Dooma Taluk of Tinsukia district. They originally came to other parts of Assam during British times, and were resettled here along with other communities following the massive 1950 Assam earthquake. The magnitude 8.6 quake devastated entire regions of the state with landslides and floods. At the time, this area, called Philobari, was dense forest, but it has been developed with extensive government assistance.

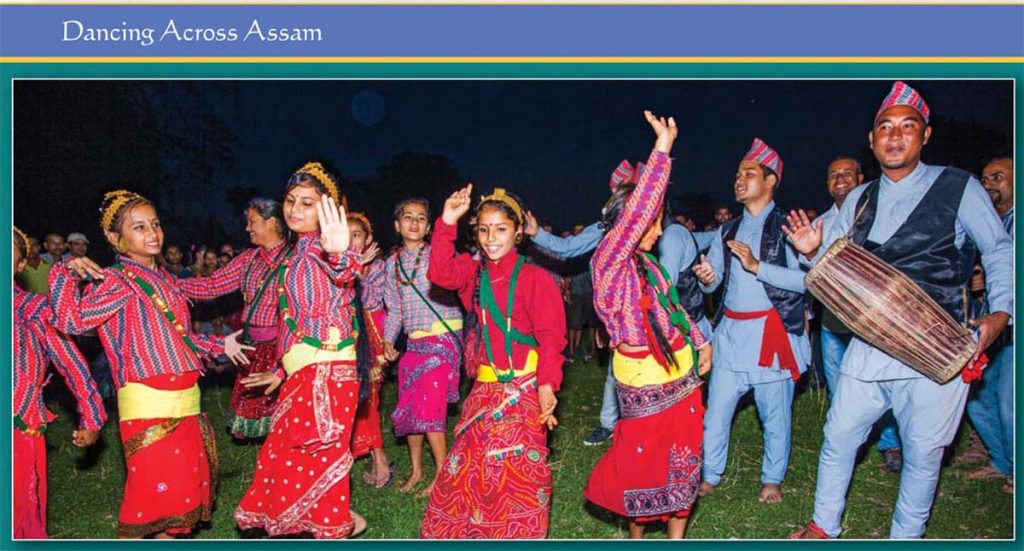

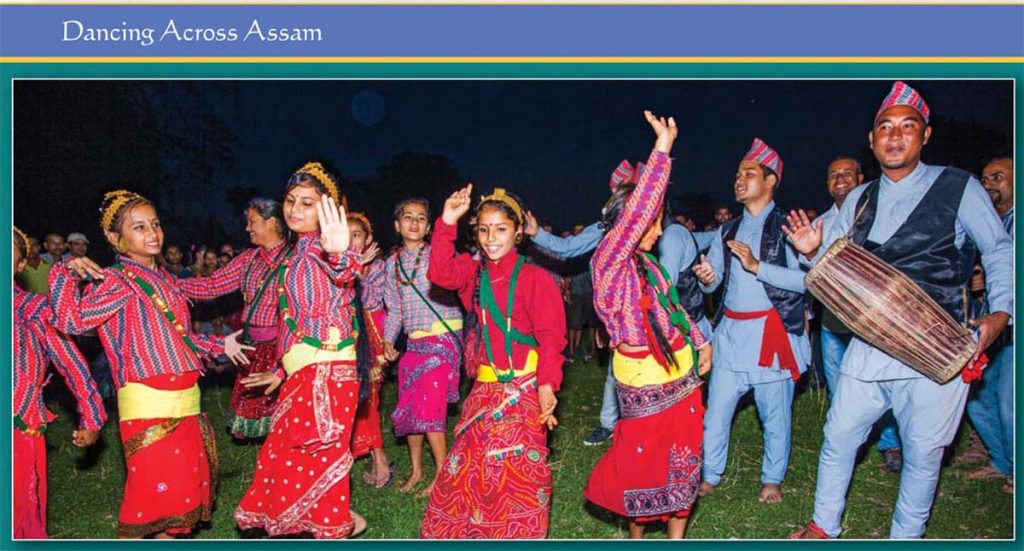

We are welcomed by a few hundred people in an event organized for our visit, a highlight of which is the performance of traditional Nepalese dances by the young boys and girls. They are delighted when our Kathmandu-based photographer, Thomas Kelly, addresses them in fluent Nepalese. The hardworking community, now numbering about 50,000, is doing well financially in agriculture, as tea estate workers and in other businesses. They have some temples in Nepalese style, but also worship in the area’s Hindu temples and visit the nearby naam ghars.

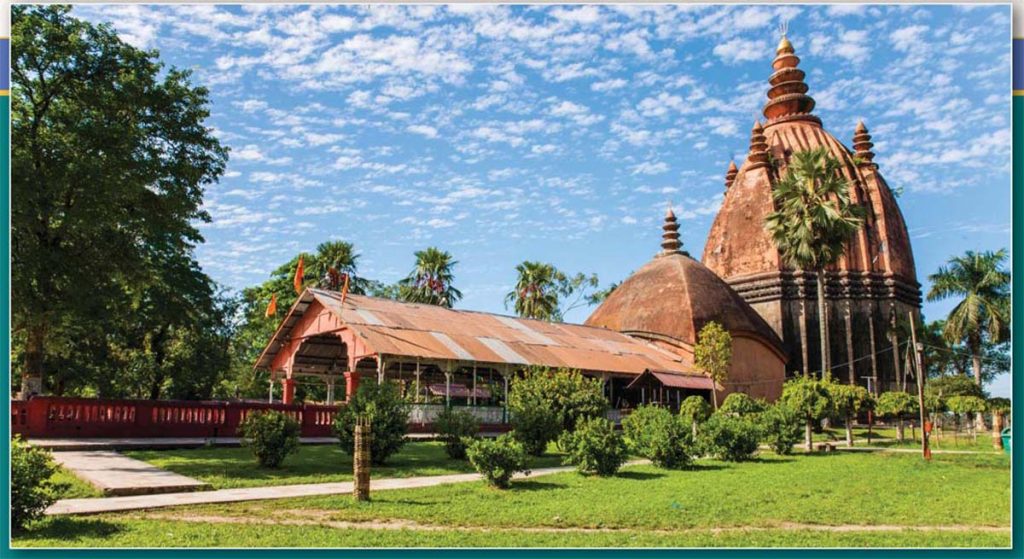

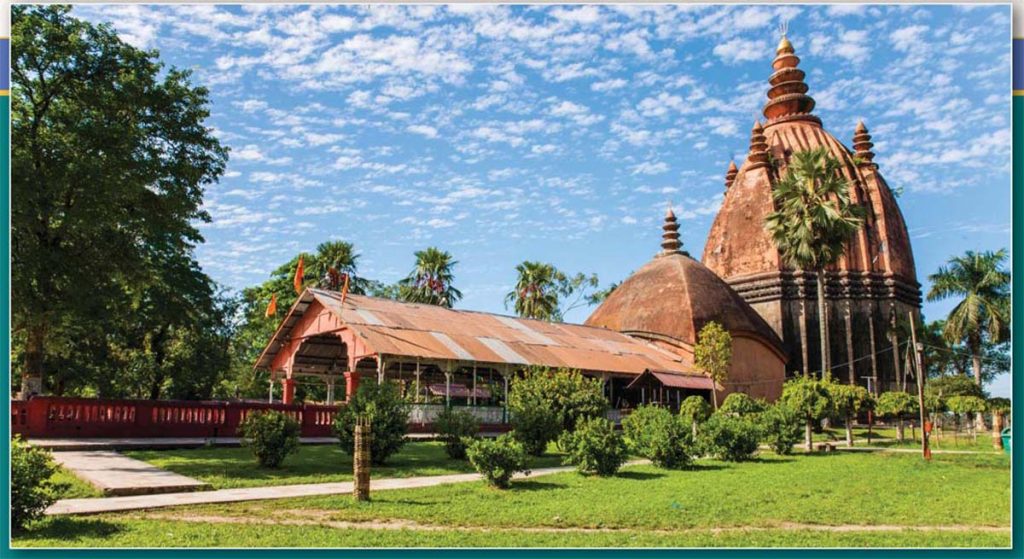

Temples of Siva Sagar

Fifty miles southwest of Dibrugarh is the famed ancient temple popularly known as Sivadol, located in the town of Siva Sagar, former capital of the Ahom kingdom. It sits on the banks of the large Siva Sagar tank or reservoir, a half mile on a side. Sivadol is a majestic example of Ahom temple architecture with a center tower over one hundred feet tall—one of the highest pre-modern structures in India, we are told. Nearby are located the smaller Vishnudol and Devidol temples in the same style.

There is no murti of Siva installed in the inner sanctum of this unusual and quite powerful temple. As shown in the picture on page 31, there is simply a hole in the altar where the Lingam would normally be placed. The worship is conducted to this unseen Lingam. The chief priest, Suresh Badthakur, explains, “The God here is formless, and one can use one’s imagination to visualize His own form and worship.” Siva here is known as Mukti Natha, which means He who grants liberation to those who worship Him. Badthakur shows us the sacred shaligrams in the main sanctum, for which he alone is allowed to conduct the worship. Representing Vishnu, their significance in this Siva temple is unclear to me.

A senior temple official, Ganga Prasad Barguhai, 83, tours us about the grounds and relates the history of the Ahom people and the temple. The Ahom originated in south China and came to Assam via Myanmar in 1228 under the Tai King Sukapa. Ahom means “undefeated,” while the “Tai” are a large group of people in southern China and southeast Asia who speak related languages, including the people of Thailand, Laos, Myanmar and the southern part of the Chinese province of Guangxi. Today the Ahom people speak Assamese. In 1671, at a key moment in India’s history, the Ahom general Lachit Borphukan stopped the eastward expansion of the Mughals by defeating their forces near Guwahati. Had he failed, the entire northeast might have come under Muslim domination.

“King Sukapa,” Barguhai told us, “brought with him a complete civilization which included the Furalong religion, medicine, agriculture and dairy farming.” The Ahom were originally Buddhists, then in 1654 King Jaidhava Sing adopted Hinduism. The Ahom still follow some of their ancient traditions, especially in their worship of ancestors.

The stone-and-brick Sivadol temple, 195 feet in diameter and 104 feet tall, was built between 1742 and 1744 by Jaidhava Sing’s great grandson Sivasinga and his wife Ambika Devi. Sivasinga invited priests from Ujjain—Badthakur’s ancestors—to come and serve in this temple. Other kings brought priests from Bengal to serve in the many Hindu temples they built across Assam. On account of its age, Sivadol comes under the jurisdiction of the Archeological Survey of India. Barguhai complains that the ASI bureaucracy makes it difficult to maintain the temple properly. The outer walls are adorned with stunning sculptures, especially of the many forms of Goddess Durga. In one corner, bells are hung and red threads tied, as at Tilinga Temple. Sivadol’s largest annual festival is Mahasivaratri.

Here we encountered Ashini Kumar Chetia, 42, chief advisor to the All Tai Ahom Students Union at the Sivadol Temple. The organization’s purpose is to preserve the ancient monuments of Assam and to nurture the Ahom culture. “We call ourselves Hindus, but our Ahom culture is different than Hindu culture. For example, our way of worshiping is different. At the Siva Sagar temple, we can, if we want, request the puja be conducted by our own priests in Ahom manner. We worship not the usual Hindu Gods, but an esoteric power named Shundev. The animal sacrifice that is done here is not part of our tradition. There are four million Ahom in Assam, mostly landowners engaged in agriculture. All of us, our youth in particular, love our culture.”

The 129-acre temple tank is a marvel in itself, as its banks maintain a water level ten feet above the adjacent ground level. The average depth is 27 feet, and the source of the water is unknown. Auspicious in its own right its water is used during festivals and social occasions such as marriages. The tank is also a popular picnic area for the local population.

Here we met Purvi Rajkunwar, 28, a member of the Ahom community who said she considers herself a Hindu and worships Lord Siva. “As do other Assamese, we also follow the philosophy of Sankardev and visit the naam ghars. We worship the Sivalingam, but not idols. In our homes you will find pictures of the Gods and Goddesses, but not statues as such. Our young girls are as free as our young boys; both are given equal love and equal opportunity.”

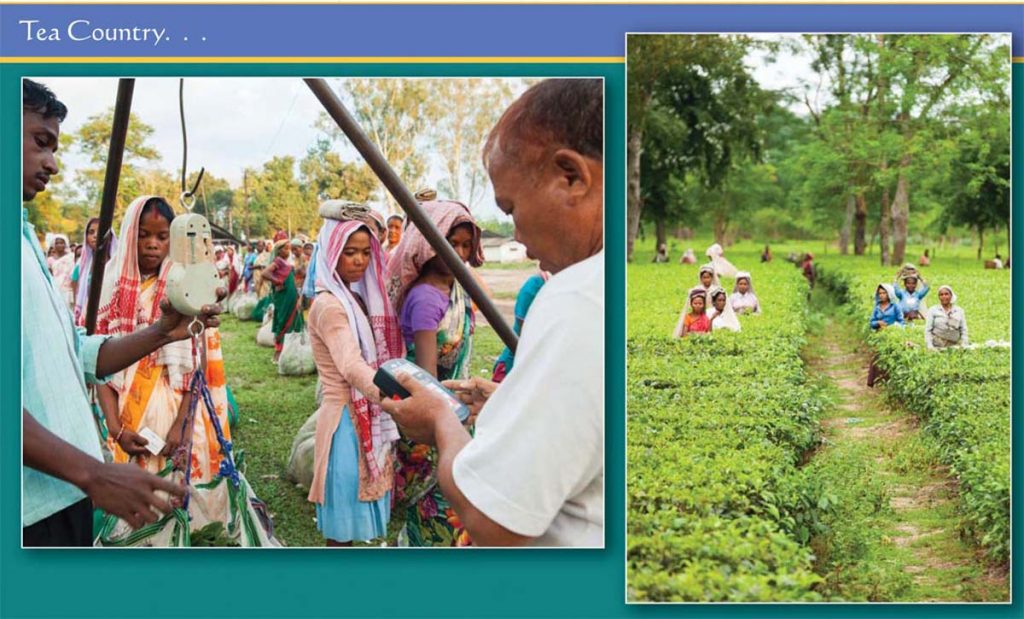

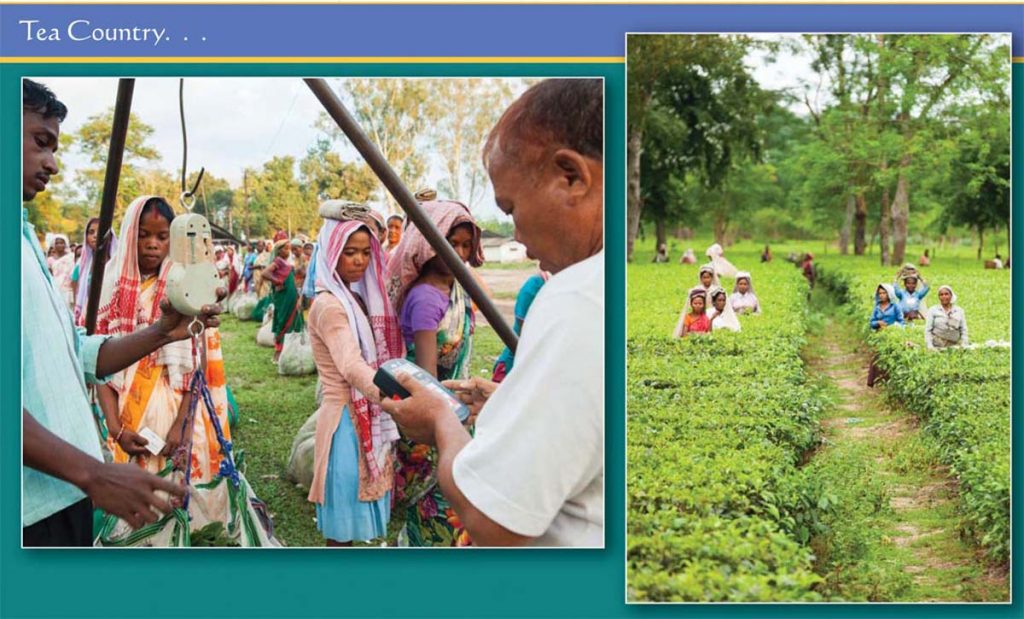

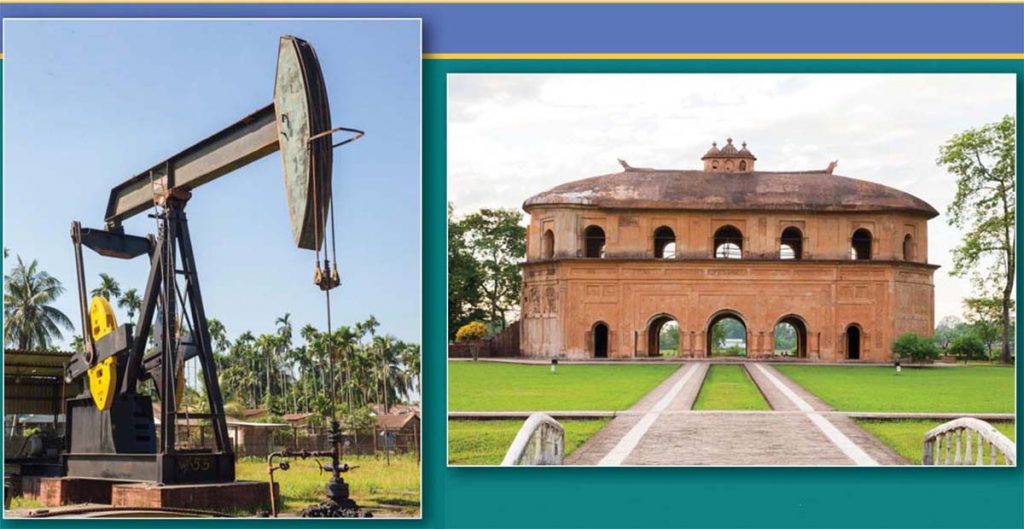

Dibrugarh Area

Dibrugarh is called the Tea City of India. Located 439 kms east of Guwahati, it is the center of industry, communication and health care for the upper Assam region. Here we mostly visited the local headquarters of the same organizations we encountered in Guwahati.

By chance in Dibrugarh we encounter a tribal dance festival underway near a tea shop where we stop for refreshments. This is the annual Karam festival for the children of the tea estate workers. These workers came around 1860 during the British era—about the same time the Nepalese arrived. The workers hailed from a group of small princely states known as Chota Nagpur, now part of the modern Indian states of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and West Bengal. Karam Devta, honored in this dance festival, is a God of power and youth worshiped in Chota Nagpur and adjacent areas.

Two-thousand students attend the English-medium Sampoorna Kendra Vidyalaya school. Principal S. P. Suresh explains this is a private trust set up to promote Indian culture and values. “Earlier, only the three missionary schools in Dibrugarh were English medium, and the cream of our society opted for them. In fact, I can say we have reduced the influence of these missionary schools by setting up our own well-managed institutions.”

We next meet with local RSS leaders at the clinic of Dr. Ramesh Agarwal, an eye specialist and head of Dr. Hedgewar Sewa Samiti. Dr. Agarwal tells us that just a few years back people here were not very familiar with the RSS, its activities or ideology, but now there is more appreciation for their work. A major topic of discussion at the meeting is the high and unabated rate of infiltration into Assam from Bangladesh, which is impacting Assamese life in not only the cities but in the villages and tribal areas. The other major challenge to Assamese life is the Christian missionaries’ concerted efforts to convert the tribals.

“Our approach to the tribals,” explained Dr. Agarwal, is to allow them to preserve their distinct identity and way of worship. At the same time we tell them that their worship and identity is very close to that of Hindus and Hinduism. They are not different from us. They face the same pressure from urbanization to change their culture as does the rest of Hindu society.”

“As to youth,” he went on, “the Bangladesh infiltration has made them aware that our whole existence is under threat. The long-term fear is that Assam will be captured and annexed to Bangladesh. In India, after Kashmir, it is Assam with the highest Muslim population by percentage. Most Indians are unaware of this.”

Another volunteer, Dr. Mukul, an engineering professor at Dibrugarh University, said when he was young, the Muslims of his village would participate in the Hindu festivals and all lived in a cordial manner—just a few decades back. “In the nineties it all changed when Bangladeshi immigrants took over as imams,” Mukul explained. “The Muslim community stopped participating in the Hindu festivals, and the women even started wearing burkas—a very big shift.”

While in Dibrugarh we visit the Ekal headquarters, situated in a huge campus in a posh locality. A lively training program is in progress for the artists who go with musical instruments from village to village singing bhajan, dancing and holding satsang. Through these sessions the Ekal movement has been able to establish a strong personal bond with the villagers of the areas where Ekal projects are running. The villagers, in turn, are very helpful with the Ekal projects, especially the schools for their children. Besides the Ekal, the RSS, Vivekananda Kendra, Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram, Vidya Bharti, VHP and Sewa Bharati all work in this area.

One Ekal supporter and member of Vidya Bharati, Dinesh Modi, stated, “In the India of the 18th century, according to a British survey, there were 720,000 gurukulam schools running in the country. The British made a deliberate move to disrupt this traditional education system and introduce a new one. Now Vidya Bharati is running 18,000 schools in India to connect to our roots through our ancient system while incorporating the modern one.”

Conclusion

Our nine days of intensive travel through Assam’s cities, villages and tribal areas impress me strongly with the relaxed outlook on life, inherent religiousness, affectionate behavior and loving nature of the Assamese people. The beauty and essence of Assam lies in its multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic and multi-religious society. Here one finds all three main streams of Hinduism: Shakti worship at the Goddess Ma Kamakhya temple, Siva at the temples of Siva Sagar, and Vaishnavism throughout. This great diversity encapsulates the whole of India in the one state of Assam. No wonder it is called an India in miniature.