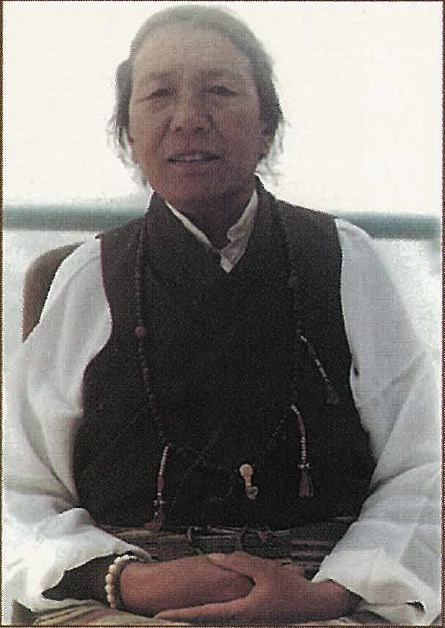

BY ADHE TAPONTSANG

When Adhe Tapontsang left Tibet in 1987, she did so on the condition of never telling anyone about the atrocities of her 27 years in Chinese prisons, nor of Tibet’s subjugation. But she felt compelled to inform the world of the inhuman conditions in those prisons and the destruction of the country’s Buddhist monasteries. Through nearly three decades of malnutrition, beatings, physical labor and solitary confinement, Adhe, 65, never wavered in her compassion. Her strength, determination and selflessness during those horrific years was borne of constant adherence to religious perspectives and practices, which is what we focus on in the following excerpts from her new book, Ama Adhe, The Voice That Remembers: The Heroic Story of a Woman’s Fight to Free Tibet.

Throughout my imprisonment, I always prayed to my tutelary deity–Dolma, the Protectoress–but found it increasingly difficult to concentrate on the long, 21-verse prayer that my father had taught me. Perhaps due to starvation clouding the mental faculties, I found that my mind would go blank at certain points in the prayer. I simply couldn’t remember, which was very discouraging. It was also impossible to pray in my free time without being interrupted either by guards or by other prisoners. One time the opportunity arose to consult an imprisoned lama, Kathong Situ Rinpoche, regarding this problem. He seemed quite moved to hear of my predicament, and taking my hand, he looked into my eyes and gently said, “Under this situation we have no time of our own to devote to traditional practices, so I will teach you this shorter prayer, and you can recite it with the same devotion. I am glad to know that your spiritual practice is still of such concern to you.” He then taught me an abbreviated prayer of nine verses to Dolma, which was to become my refuge in all future times of trial and loneliness.

One time, after having worked and weakened for some months, I slept for a week and stopped working. I decided the system was such that you had to work and then had so little to eat that you’d most probably die of starvation. The only thought I had was, “I am going to die here,” so I tore a strip of cloth from the bottom of my blouse and, making one hundred and eight knots, fashioned it into a rosary. I felt that to do some religious practice was the only thing left for me. During that period of solitary confinement, I recited the Dolma prayer as long as my strength held out. I would recite, then fall unconscious. I would wake up again and try to walk while reciting the mantra, then I would fall down. From that time until I decided to try working again, the guards didn’t give me any food. Finally, one day, a feeling came over me that I should not try to force the end of my own misery, and decided to go back to work.

One time I was given some extra food by a family member who visited the prison. I decided to share it with all the prisoners, one of whom was Kathong Situ Rinpoche, who had taught me the Dolma prayer. He said, “In independent Tibet, we used to have many rich families sponsoring meals and teas in the monasteries. We can understand that situation because of their wealth. But today, your sharing of this food with everyone has far more meaning. You have done a greatly meritorious work, and you will live. But for us, there will only be death. There will be no way to escape from this atrocity.”

As I left Gothahg Gyalgo prison for a different camp, we walked slowly through the places where all the starved prisoners had been buried, and I realized that my own remains could easily have been left there. As we passed the graves, I silently spoke to my fellow prisoners, saying, “If only you had survived a little longer, you would be walking with us today.” I prayed to all the deities of Tibet for their departed spirits, that they have a good rebirth, and promised that all through my life I would pray for them. It was as if one’s own relatives were buried there because we had all endured the same suffering.

In Minyak Ra-nga Gang region there is a sacred mountain known as Sha Jera, traditionally a place of pilgrimage for festivals and religious occasions. People of the region offered prayer and incense ceremonies. In the early 1970s, over 300 prisoners were employed in mining lead from the mountain. At its base is a small lake. During the summer of 1975, this lake was the site of what was regarded by us Tibetans as a miraculous event. One day people noticed that an impression of a nomadic tent had manifested beneath the water in the middle of the lake. The Chinese took binoculars up on the mountain to monitor whether the image was moving. They realized that the image was not a natural occurrence, and it frightened them. After a week, the image of the tent began to disappear and a very large green lotus began to physically grow in its place. The flower continued to spread over the lake. The people said that the flower had great significance because of its size and color: green is associated with His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, who was born in the year of the Wooden Hog. Green is the color of the wooden element. Tibetans came to the shore in great numbers. Before long, the Chinese decided to bombard the lake. As a wall of water rose in the lake’s center, people rushed to pick up the pieces of the flower that floated to the shore. Those managing to preserve the flower’s fragments said the petals had the consistency of grass. We Tibetans felt that the apparition and the extraordinarily large lotus held promise of better times to come.

TO READ ABOUT AMA ADHE’S PRISON LIFE IN VIVID DETAIL, ORDER AMA ADHE, THE VOICE THAT REMEMBERS, FROM: WISDOM PUBLICATIONS, 199 ELM STREET, SOMERVILLE, MASSACHUSETTS 02144 USA