By Dr Kusum Pant Joshi

By the early 1900s, Europe and America had seen non-Indians performing their own melange inspired by Indian dance (like Ruth St. Denis) or temple dancers, the devadasis. It was then that a new wave of artists dazzled the West with superb performances, Indian in style but European in stagecraft.

This came about because of a benign confluence of art lovers. On one side were the liberal British intelligentsia, who turned their eyes to the East and liked what it saw. From another side, the most successful ballerina of her time, the influential Anna Pavlova, exerted her might to revive the arts of Indian dance.

THE UK’S AWE FOR INDIA

The shift in the West’s perception of India was gradual but decisive. In Britain, it started in the first decade of the 20th century. Key proponents included Sir William Rothenstein, artist and Principal of London’s Royal College of Arts; Dr. Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy, an archaeologist turned art historian and Indophile; and a small group of leaders from various art fields.

This pro-India movement was sparked by a quarrel. In a meeting of London’s prestigious Royal Asiatic Society on 13 January, 1910, Sir George Birdwood expressed contempt for Indian fine art, saying its symbolism “outrages artistic sensibilities, virtually regarding art as but a framework for its myths, and allegories, and strange semiological devices.”

Disgusted by Birdwood’s narrow interpretation, Sir William Rothenstein and his group published a letter in support of India’s distinctive creative genius. His manifesto in The Times (the newspaper read by the British cultural and social elite) was signed by 12 important Britons in the fields of painting, sculpture, decorative arts and art education, including George Frampton, a prime founder of the New English Art Club; Charles Waldstein, archaeologist and Slade Professor of Fine Arts at Cambridge; and William R. Lethaby, a highly influential architect. (Read their India-friendly manifesto on page 31.)

India’s champions among the British intelligentsia did not confine themselves to the realm of words. They promptly set up the India Society, aimed at familiarizing people in the West with Indian art and culture. They created new publications about India and organized talks and exhibitions.

The India Society’s leading members, such as Rothenstein and Lady Christiana Herringham, utilized their strategic links with established British art groups. The Art Workers Guild and the New English Art Club, for example, assisted in featuring the work of eminent Indian painter-engraver Mukul Dey and also displayed copies of his Ajanta paintings.

Earlier India extravaganzas in the West had portrayed Indian culture as primitive, glorifying the British Empire and the impact of British colonial rule on India. The India Society’s exhibitions were distinguished by their positive intent. Along with other sympathizing organizations, they wanted to inculcate a better understanding and appreciation of Indian art and creativity in the West. In large part, they succeeded.

A RUSSIAN GODMOTHER FOR INDIAN ART

The most important European dancer of the early 20th century was Russian prima ballerina Anna Pavlova, a friend of Rothenstein. Widely regarded as one of the finest classical ballet dancers in history, Pavlova held India and India’s art and culture in high esteem.

When she first visited India, she yearned to witness classical Indian temple dancing, but all she could find were amateur girls dancing. Indian dancer Ram Gopal describes her search: “She implored the wealthy and educated Indians to show her something of the mystic and exquisite Hindu dances she had always somehow known India possessed tucked away in her remote vastnesses, and yet the invariable reply Pavlova got was that temple dance did not exist in India any longer! Kathakali, Kathak, Bharatanatyam–these were as hidden and unknown to the immortal Pavlova as they were to the wealthy and socialite Hindus. The classic dances, she was told repeatedly on both her tours to India, were dead.”

The late 19th century reformist movement, spearheaded by British administrators and Western-educated Indians, had labeled devadasis as “temple prostitutes,” successfully driving them underground, away from the public eye. But Pavlova never gave up. In her travels and performances around the world, she met talented Indian artists. Her desire to meet India’s legendary temple dancers, combined with her stature as a classical artist, inspired some of them to return to their homeland to seek out, salvage and develop their own ancient Indian classical dance heritage.

Pavlova eventually found three immensely talented young Indians with the potential to become traditional dancers but who were pursuing other careers. They were Uday Shankar, an aspiring painter; Leila Roy, a musician; and Rukmini Devi, a classical ballerina that looked like “a double of Olga Spessivtseva,” in Ram Gopal’s words. By convincing the trio to return to their roots, and by teaching them the secrets of modern stagecraft and theatrical production, Pavlova had a momentous impact on Indian classical dance.

Pavlova’s love for India had a profound effect on Western classical dance as well. So impressed was she by the ethereal beauty of the paintings in the Ajanta caves that, not long after returning from her first Indian tour in 1922, she developed a ballet called Ajanta Frescoes. Under Indian inspiration, Pavlova also developed Hindu Wedding and Radha and Krishna, traditional ballet choreographies infused with India’s color and vibrant orientalism.

UDAY SHANKAR

Foremost among those inspired by Pavlova was Uday Shankar. Before meeting Anna Pavlova, he had planned to be a painter. In 1920 he enrolled at the Royal College of Art in London, where he distinguished himself and won a prestigious award. This attracted the attention of Rothenstein, head of the fine arts section of the College, who took young Uday as his protege.

Destiny would bring interesting turns. Uday’s father, Dr. Shakar Chattopadhyay, a Sanskrit scholar with an MA in political science from the University of Geneva, was also a sensitive man with artistic inclinations. Wanting to honor Indian soldiers who were distinguishing themselves while fighting alongside Allied forces in the First World War, Dr. Chattopadhyay wrote and produced a ballet and asked his talented son Uday to create the choreography. The ballet was staged in London’s Covent Garden, raising funds to help Indian war veterans.

The details have been lost to history, but during that production Uday and Pavlova met. Soon after, Uday left the Art College to pursue dance. Rothenstein, who held his Indian protege in high esteem and had great expectations of him as a painter, was disheartened: “I urged Uday Shankar to reconsider his decision. Later I learned that Uday had joined Pavlova in America. I thought of him as a lost soul.”

Despite Rothenstein’s disappointment, he was awestruck when he later saw Uday Shankar perform. “I saw at once I had been wrong; Uday Shankar’s dancing, his poise and gestures, had grace and gravity. The musicians had the same gravity as they sat before their sitars, vinas and drums. And the women! What exquisite gestures in their hands, what reticence in their movements. I had been shocked more than once seeing so-called Indian dances by [Western] women whose immodest dress and movements were entirely without the delicate sensuality of the Indian Bayaderes. There was a religious atmosphere throughout Uday’s entertainment. I went behind after the performance to offer my congratulations. Catching sight of me, he at once left the circle surrounding him and bending low, to my embarrassment, he made the gesture to take the dust from my feet.”

Uday Shankar’s success as a dancer in Europe in the 1930s was due in no small measure to his association with Pavlova. He worked for about a year as a choreographer and dancer in her ballet company, touring Europe. During this time, Pavlova gave him invaluable insights and experience that molded his future career as an Indian dancer on the world stage.

Working with Pavlova shaped Uday into a disciplined artist and familiarized him with the essential elements of successful stagecraft. Above all, she goaded him to develop his dance not by looking westward, but by turning his gaze towards the traditions of India. It was she who urged him to seek inspiration from the treasure house of his own Indian cultural background, folklore and heritage.

During the late 1920s, Uday Shankar and his associate Alice Boner spent a year traveling all around India. Alice was a Swiss sculptor and designer who loved India. They used the tour to observe, learn and acquire whatever they felt would be useful in fulfilling their artistic aims. They examined ancient Indian sculpture and paintings in the Buddhist caves at Ajanta and the Hindu temples of Orissa and the Deccan. They observed various Indian dance styles, both classical and folk. To enlarge his repertoire as a dancer, Shankar made a selection from the gamut of Indian hand gestures (hasta mudras) and gained mastery of the nine basic emotions–the navarasas–described in Bharata Muni’s ancient Indian dance treatise, Natya Shastra.

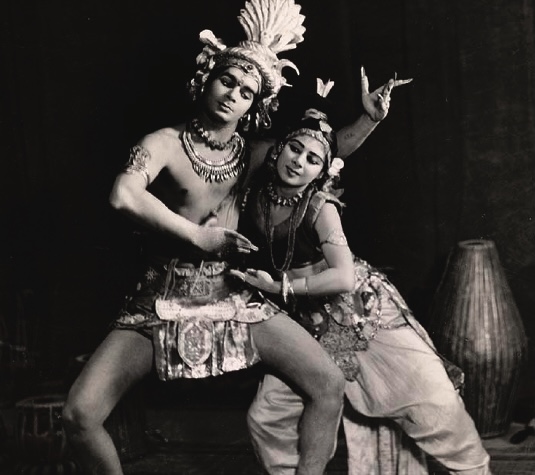

Uday Shankar never tried to perfect a specific Indian dance style. Instead, he picked whatever appealed to him from every dance style he saw. His Uday Shankar Company of Hindu Dancers and Musicians reflected his confidence and the sweep of his creativity and ambition. He built up and carted with the tour an array of 150 musical instruments, including the sitar, vina, sarangi, sarod, wind instruments like the shehnai and various flutes as well as diverse percussion instruments from all over India. Before setting out from India, he also roped in some of his close relatives, most importantly his little brother Ravi Shankar, who would one day become a world-famous sitarist.

A TRIUMPHANT DEBUT IN PARIS

Once back in Europe, the troupe rehearsed rigorously for their debut at the Theatre des Champs Elysees on March 3, 1931. Success smiled on them, and the Uday Shankar Company of Hindu Dancers and Musicians was a big hit in France. Shankar would go on to become a pioneer of modern dance in India, a world-renowned Indian dancer and choreographer. Known for adapting Western theatrical techniques to traditional Indian classical dance, he effectively placed Indian dance on the world map.

His programs often juxtaposed contrasting forces or qualities. Though the style, spirit and theme of his dances were Indian, they were meticulously planned, crafted, cut to size, fitted to Western tastes, shorn of repetitious movements and presented with modern lighting effects. Secondly, he introduced diversity and color to generate a variety of moods. He utilized orchestral music as well as ancient and classical dance themes, all the while emphasizing the strengths of Indian dance, such as the exquisite play of opposites in Siva/Shakti dances. Thirdly, with the help of Alice Boner, he paid attention to details of dance costumes, jewelry, music and props. Finally, in keeping with the original purpose of Indian dance, his performances had an uplifting, spiritual quality.

Shankar enthralled European audiences and left them with a deep impression of the beauty, mystique and grandeur of Indian dance. But his mentor, Pavlova, never saw his triumph. She contracted pneumonia in January, 1931. When her doctors told her she would survive but never be able to dance again, she refused any treatment; “If I can’t dance, then I’d rather be dead.” Three weeks later she died, days before her 50th birthday and barely a month before Shankar’s debut in Paris. But Anna, creator of the role The Dying Swan, had forever changed the course of both Eastern and Western dance.

THE MAGNETIC MADAME MENAKA

Another dancer inspired by Pavlova was Madame Menaka, whose original name was Leilawati Roy. She was born in Barisal, (now in Bangladesh) in 1889 in an affluent landed Brahmin family. Her father, Pearey Lal Roy, was a lawyer. After qualifying as a Barrister from London’s Lincoln’s Inn in 1880, he had settled in Calcutta where he rose to the position of Public Prosecutor. Her mother, Lolita Roy was a progressive Bengali woman. Well-known as a Suffragist and promoter of Indian interests in London, Lolita had moved to the UK with Leilawati and her five other children to London in 1901. Leilawati was a student of St Paul’s School, Hammersmith, where she showed remarkable musical talent and felt drawn to the stage. But performing in public was then not considered respectable , and her father had reportedly discouraged her.

After Leila moved to India with her sister, Mira Chatterjee, the two defiantly joined a dance group set up by Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay and her Bohemian poet/actor husband Hirendranath Chattopadhyay. Leila’s friendship with Princess Indira Raje, of the princely state of Baroda, also exposed her to the arts. At that time, she was a flute player, not a dancer. Anna Pavlova, who was also an acquaintance of the Princess, befriended Leila and encouraged other aspirations.

Her formal training in dance began after she married Colonel Dr. Sahib Singh Sokhey, another friend of the Princess of Baroda, a scientist in the Indian Medical Service of the British Indian army. Sokhey possessed the sensitivity of an artist and was quick to spot the artistic vision and cultural potential of his talented wife.

With her husband’s support, Leila was availed the best teachers and soon mastered Kathak dance. Though she was a bold woman, she was also a traditionalist who loved the purity of Indian dance and arts. She associated with artists and patriots involved in India’s struggle for freedom from British rule, such as Rabindranath Tagore, poetess Sarojini Naidu and Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, an active supporter of India’s traditional arts and crafts.

In keeping with Indian classical dance traditions, Leila regarded dance not as a method of entertaining audiences or a means of self-expression, but as an elevating spiritual activity. In an article published in 1933, she explained: “I cannot lay too much importance on the fact that one must master all the traditional technique. We must strenuously discourage all attempts to bluff the public by senseless posturing and posing on the stage. We do not want our dance to become an exotic and erotic presentation for the delectation of the West. It must express the life and emotions of our nation and not be mere ethnographic posturing.”

Leila established her own dance troupe in 1934 and started dance classes for new students from non-devadasi backgrounds at her residence. That same year, she staged her first dance drama, Krishna Leela, at the Opera House in Bombay. During her short but packed dance career, other significant new dance dramas that she choreographed and staged were Deva Vijaya Nritya (1935), Menaka Lasyam (1938) and Kaliamardan and Malavikagnimitram (both in 1939). Deferent but not bound by tradition, she discarded traditional Kathak lyrics and took the help of trained musicians to create orchestral ensembles, a break from the traditional way Indian music was played.

Thus her productions were a clever merger of traditionalism and innovation. The artistic input she received from high-caliber artists and teachers lent her work authenticity and sophistication–effects that Anna Pavlova had encouraged. After founding the Menaka Indian Ballet company, Leila became known as Madame Menaka. Her enthusiastic husband, taking advantage of a brief official trip for attending an international Intergovernmental Conference on Biological Standardisation in Geneva, launched his wife’s company on a spectacular Indian dance tour (1935-1938). The Menaka Indian Ballet found themselves dancing at important venues in numerous European capitals. Their tour culminated at the International Dance Olympiad at Berlin in 1936, where Madame Menaka won first prize. Basking in public acclaim, she was invited to the nascent movie industry, choreographing black-and-white, silent movie productions in Germany and England.

RUKMINI DEVI’S BHARATANATYAM

The third Indian artist to benefit from Anna Pavlova’s sphere of influence was Rukmini Devi Arundale, whose biography was featured in the October/November/December 2007 issue of Hinduism Today.

Rukmini Devi had first seen the famous Russian ballerina perform while visiting Bombay with George Arundale, her English husband, who was a prominent associate of Annie Besant in the Theosophical Society at Adyar. She and Pavlova became friends during a ship journey to Australia.

At the time, Rukmini Devi was solely interested in the purest Russian ballet, at which she excelled. But Pavlova urged her toward traditional Indian dance, just as she had done with Uday Shankar and Leila Roy, and encouraged her to help lift it from its precarious state.

In order to reenergize South Indian temple dancing, dedication and talent were not enough. Rukmini Devi also needed conviction and the courage to flout social restrictions and taboos–which she had demonstrated in her controversial choice of the much older Arundale as a husband. Devi started in the 1930s with the revolutionary step of seeking out and learning the art from a devadasi, Mylapore Gowri Amma, and nattuvanars (male teachers of dance from Tanjore). While learning the dance, Rukmini Devi refined it to be socially acceptable, replacing the most erotic elements with devotional pieces.

By 1935, she performed at the Diamond Jubilee Convention of the Theosophical Society in Madras. She was dressed in a most decent fashion, in spotless white, silently proclaiming to the world the purity, dignity and spiritualism of her dance, which she presented under the name Bharatanatyam. This term, which earlier included any form of dancing along the principles enunciated by Bharat Muni in the Natya Shastra, thus began to connote (as it does today) a distinct form of classical South Indian dance.

CONCLUSION

India’s British rulers had dethroned Indian dance from its exalted position, scorning and demonizing it as cheap, erotic public entertainment instead of a sacred expression of worship. Uday Shankar, Leila Sokhey and Rukmini Devi Arundale, three artists from India’s cultured middle class, under the aegis and creative genius of Anna Pavlova, gave Indian classical dance new form, while earning recognition both in India and abroad.

They did not re-establish the devadasi system or restore classical dancing to the temples. But they democratized Indian dance, making it open to people from all classes and groups, either as performers or as part of an enthusiastic audience. With boundless creativity and a wealth of traditional resources, these three artists elegantly demonstrated to the world the timeless elan of India’s art and culture, helping dispel the notion of India as a primitive and inferior country suitable for foreign colonial rule. These were freedom fighters, wielding no weapons but beauty and grace.