HOW AND WHY TO ESTABLISH A HOLY ROOM FOR WORSHIP AND MEDITATION

What is the center of your home? The kitchen, the workshop, the living room or den? The ancients designated a crucial part of the home as a sacred sanctuary, a fortress of purity to which dwellers could retreat before dawn each day, to commune with their higher nature and with God and the Gods. This center of spiritual force is called devatarchanam, the “place for honoring Divinity.” Sacred architecture places it in the northeast corner, the realm of Isana, where its potency naturally flourishes. Scriptures speak but little of this tradition, perhaps because its necessity is taken for granted. Nevertheless, the custom has lived on, and every prominent devout Hindu home has a holy shrine room, often opulent, sometimes austere, the domiciles’ most auspicious quadrant, reserved for religious pursuits, and like a miniature temple, radiating blessings constantly through the abode and out to the community.

Love and joy come to Hindu families who worship God in their home through the traditional ceremony known as puja, meaning adoration or worship. Through such rites and the divine energies invoked, each family makes the house a sanctuary, a refuge from the concerns and worries of the world. The center of that sanctuary, the site of puja, is the shrine, mystically tied to the temple to which they pilgrimage weekly. Puja is performed daily–usually in the early morning, but also in the afternoon or evening–generally by the head of the house. All members of the family attend. Rites can be as simple as lighting a lamp and offering a flower at the Lord’s holy feet, or they can be most elaborate and detailed, with myriad Sanskrit chants and offerings. The essential and indispensable part of any puja is devotion. Without love and reverence in the heart, outer performance is of little value. But with true devotion even simple gestures become sacred ritual.

As in a temple, the images or icons of God and Gods are the focus of the shrine room. These are called murti in Sanskrit, worshiped and cared for as the physical body of the the Divine. Hindus do not worship these “idols” per se. They worship God and the Gods who by their infinite powers spiritual hover over and indwell the image. Murtis of the Gods are sanctified forms through which their love, power and blessings flood forth to bless the family. The God’s vibration and presence can be felt in the image, and the Divinity can use the images as a temporary physical place body or channel. Hindus believe and expect that the God is actually present and conscious in the murti during puja, aware of thoughts and feelings and even sensing the worshiper’s gentle touch on the metal or stone. The great Adi Shankaracharya, while espousing a strict monism, wrote, “Although Parabrahman is all pervading, to attain Him one should accept that He is ‘more’ present in one particular place, just as we see Vishnu in the Shaligrama, a small round stone.” The Vaishnava saint Ramanuja similarly stated, “Although the Lord is all pervading, using His omnipotent powers He appears before devotees to accept their devotion through an image.”

The Science of Ritual: Puja is a ceremony in which the ringing of bells, passing of flames, presenting of offerings and chanting of mantras invoke the devas and Gods, who then come to bless and help the devotees. Puja is holy communion, full of wonder and tender affections. Thus the home shrine is a place of tremendous importance, made more and more sacred by the culmulative power of prayer. Daily puja is the axis of religious life, and the puja room is the heart of the home. Chanting the Vedas is the magic enlivener. In the words of Sri Chandrasekharendra Saraswati, “The Veda mantras being the root cause of creation, the mere chanting of Veda mantras would, by their vibrations, make the Devas appear in person.”

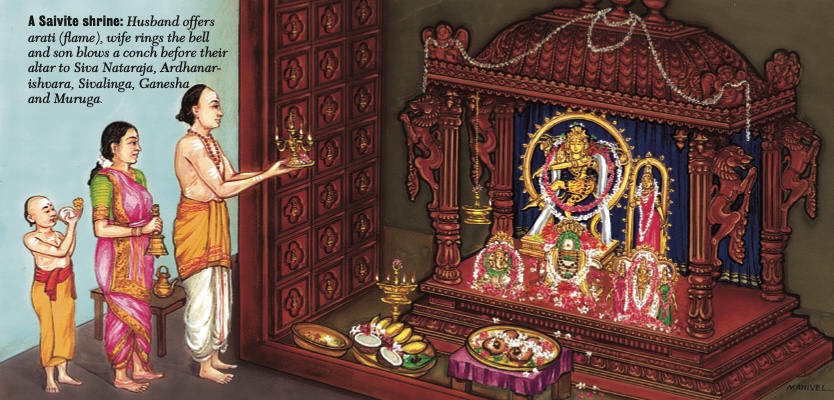

The home shrine is also the locus for private and group meditation, prayer, mantra recitation and devotional singing. Its sanctity is protected by never using it for other purposes. This space is meticulously cared for, kept immaculate and elaborately decorated to look like a small temple. It should be well-lit and free from drafts and household disturbances. The altar is generally close to the floor, since most of the puja is performed while seated. But when there are small children in the home it is often higher, as to be out of their reach. Pictured in this Insight (please see hard copy) are “typical” altars (slightly larger than life) of the four major Hindu denominations: Saivism, Vaishnavism, Saktism and Smartism. In truth, Hinduism consists of ten thousand lineages and more, each with its unique traditions, and as many variations in home altars as well. Yet, there are many similarities.

At a Ganesha shrine, for example, an icon, or murti, of the elephant-headed God is placed at the center of the altar. A metal or stone image is considered best, but if not available there are two traditional alternatives: 1) a framed picture, preferably with a sheet of copper on the back, or 2) A kumbha, which is a symbol of Ganesha made by placing a coconut on a brass pot of water with five mango leaves inserted between the coconut and the pot. The coconut is husked but the tuft of fibers at the top is not removed. Most shrines also honor a picture of the guru of the family lineage, either on the altar or adorning the walls.

Bathing the God’s image is often a central part of puja. For this, special arrangements are established at the altar to catch the sacred water or milk as it pours off the icon. Most simply, the murti may be placed in a deep tray to catch the water. After the bath, the tray is removed and the murti dried off, then dressed and decorated. More elaborately, a drain is set up so the water flows into a pot at the side of the altar. If devotees are in attendance, this blessed water is later served by the pujari (the person performing the ritual) who places a small spoonful in each devotee’s right palm.

Holy Accoutrements: Puja implements for the shrine are kept on large metal trays. On these are arranged ghee lamps, bells, cups, spoons and pots to hold the various sacraments. Available from Indian shops, these are dedicated articles, never used for purposes other than puja. Their care, cleaning and polishing is considered a sacred duty. Usual items include: 1) water cups and a small spoon for offering water; 2) a brass vessel of unbroken, uncooked rice (usually mixed with turmeric powder), also for offering; 3) tray or basket of freshly picked flowers (without stems) or loose flower petals; 4) a standing oil lamp, dipastambha, that remains lit throughout the puja; ideally kept lit all day; 5) a dipa (or lamp with cotton string wick) for waving light before the Deity; 6) a small metal bell, ghanta; 7) an incense burner and a few sticks of incense, agarbhatti; 8) sacraments of one’s tradition, such as holy ash, vibhuti; sandalwood paste, chandana; and red powder, kumkuma (these are kept it polished brass or silver containers); 9) naivedya, an offering for the Deity of fresh fruit and-or a covered dish of freshly cooked food, such as rice (never tasted during preparation); 10) a camphor (karpura) burner for passing flame before the God at the height of puja; 11) brass or silver pots for bathing the murti; 12) colorful clothing for dressing the murti; 13) flower garlands; 14) additional oil lamps to illumine and decorate the room; 15) a CD or tape player.

Purity: Before entering the shrine room, all attending the ceremony bathe and dress in fresh, clean clothes. It is a common practice to not partake of food at least an hour or more before puja. The best time for puja is before dawn. Each worshiper brings an offering of flowers or fruit (prepared before the bath). Traditionally, women during their monthly period refrain from attending puja, entering the home shrine or temple or approaching swamis or other holy men. Also during this time women do not help in puja preparation, such as picking flowers or making prasada for the Deity. Use of the home shrine is also restricted during periods of retreat that follow the birth or death of a family member.

Worshipful Icons: As seen in the main illustrations, the images enshrined on home altars vary according to lineage and denomination. All icons, however, are either anthropomorphic, meaning human in appearance; theriomorphic, having animal characteristics (for example, Lord Hanuman, the monkey God); or aniconic, meaning without representational likeness, such as the element fire, or the smooth Shaligrama stone, worshiped as Lord Vishnu. Other objects of enshrinement include divine emblems or artifacts, including weapons, such as Durga’s sword; animal mounts, like Siva’s bull; a full pot of water, indicating the presence of the Devi; the sun disk, representing Surya; the holy footprints or sandals of a God or saint; the standing oil lamp; the fire pit, mystic diagrams called yantra; water from holy rivers; and sacred plants, such as the tulsi tree. All these are honored as embodiments of the God or Goddess. The Vedas enjoin: “The Gods, led by the spirit, honor faith in their worship. Faith is composed of the heart’s intention. Light comes through faith. Through faith men come to prayer, faith in the morning, faith at noon and at the setting of the sun. O Faith, give us faith!”

DO HINDUS WORSHIP IDOLS?

By Sadhu Shantipriyadas,, Swaminarayana Fellowship

From the moment the Vedic rites are completed and a statue or painting of the Deity is consecrated, the Lord through the image manifests all His glory and grace. He accepts various devotions. He listens to prayers and woes. He is at once a confidante and giver of blessings. Thus, an image cannot be said to be merely a beautiful statue or doll, nor an excellent painting. The image is God.

Said Swami Vivekananda, “It has become a trite saying that idolatry is bad, and everyone swallows it at the present time without questioning. I once thought so, and to pay the penalty of that, I had to learn my lessons sitting at the feet of a man who realized everything from idols. I allude to Ramakrishna Paramahansa. Yet, idolatry is condemned. Why? Some hundreds of years ago, some man of Jewish blood happened to condemn it. He happened to condemn everybody else’s idols except his own. If God is represented in any beautiful form or any symbolic form, said the Jew, it is awfully bad; it is sin. But if He is represented in the form of a chest with two angels sitting on either side, it is the holiest of holies. If God comes in the form of a dove, it is holy. But if He comes in the form of a cow, it is heathen superstition, condemn it…”

Over the centuries, in their condescending haste and missionary fervor to convert the rest of the world to the “One and only correct faith, and to commit the souls of the otherwise damned to God,” various religions have condemned image worship with fanatic zeal. This has led to a shallow refutal of image worship and a misinterpretation of the Hindu image worshiped. To complicate the issue, image worship is also frowned on by some professing Hindus.

The question of image worship will be debated for years to come. Here it suffices to say that with the ancient Hindus image worship was not left to be treated as an ignorant and useless practice fit only for the ignorant and spiritually immature; even the greatest visited mandirs and worshiped images, and these thinkers did not do so blindly or unconsciously. A human necessity was recognized, the nature of the necessity was understood, its psychology systematically analyzed, the various phases of image worship, mental and material, were defined. The modern Hindu follows in footsteps of his forebearers. Through the image, the eye is taught to see God, and not to seek God. The first lesson received at the sanctum is to be applied everywhere: see God in everything!

A HINDU HOME IS MORE THAN A HOUSE

By V. Ganapati Sthapati,, Master Architect, Chennai

In Indian architecture, the dwelling is itself a shrine. A home is called manushyalaya, literally, “human temple.” It is not merely a shelter for human beings in which to rest and eat. The concept behind house design is the same as for temple design, so sacred and spiritual are the two spaces. The “open courtyard” system of house design was the national pattern in India before Western models were introduced. The order introduced into the “built space” accounts for the creation of spiritual ambience required for the indweller to enjoy spiritual well-being and material welfare and prosperity.

At right (please see hard copy) is a typical layout of a square building, with a grid of 9×9=81 squares, meant for family persons (for yogis, scientists and artists, a grid of 8×8=64 is prescribed). The space occupied by the central 3×3=9 squares is called Brahmasthanam, meaning the “nuclear energy field.” It should be kept unbuilt and open to the sky so as to have contact with the outer space (akasha). This central courtyard is likened to the lungs of the human body. It is not for living purposes. Religious and cultural events can be held here–such as yajna (fire ritual), music and dance performances and marriage.

The row of squares surrounding the Brahmasthanam is the walkway. The corner spaces, occupying 2×2=4 squares, are rooms with specific purposes. The northeast quarter is called Isana, the southeast Agni, the southwest Niruthi and northwest Vayu. These are said to possess the qualities of four respective devatas or Gods–Isa, Agni, Niruthi and Vayu. Accordingly–with due respect to ecological friendliness with the subtle forces of the spirit–those spaces (quarters) are assigned as follows: northeast for the home shrine, southeast for the kitchen, southwest for master bedroom and northwest for the storage of grains. The spaces lying between the corner zones, measuring 2×5=10 squares, are those of the north, east, south and west. They are meant for multi purposes.

For home worship, griha puja, the Deity icon should be smaller in size than in a temple. The agreeable and generally recommended height of the standing image without pedestal is one’s own fist (mushti) size, measured with the thumb raised.