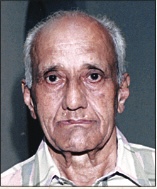

By Captain M.S. Srikantaiah

I am in my early eighties now. when I look around me, I feel sad for the younger generations who have not experienced the joys of a joint family’s upbringing. They do not know what they are missing in the form of the love and comfort of a joint family, particularly those little children today with both parents working.

My father died before I was born and my mother died when I was barely four. I was raised in a joint family. It was a beautiful well-patterned system. Command came from my grandfather, the senior-most man in the house. This command was neither disobeyed nor questioned. My grandfather, a lawyer by profession, would look after everything in the family. I was the youngest in my family of five siblings. Along with us were other uncles, aunts and cousins we all lived under the same roof. Besides, we had nearly a dozen students, who were either orphans or were not well-to-do financially, living with us. My grandfather had taken over the responsibility of looking after them, too. He never differentiated between the children, whether related to him or otherwise.

My grandfather had a remarkable way of disciplining us. He was strict, no doubt. But he would never scold us. Beating was unheard of. None of us feared him or, for that matter, feared anything. His way of disciplining was in the form of love and affection, which was given in abundance to all of us equally. As a child who grew up not seeing his parents, I hardly even realized that I was an orphan, even in my adulthood. He was fastidious about making good use of time. No work should be postponed. If something was not done on time, he would say nothing, but get down to doing it himself.

There was another wonderful quality in him, which as a grandfather I have failed to reflect. Whenever we went to him, he would give us a pencil, slate or a packet of sweets. Never did he say “No” to a child. He would regularly buy the seasonal fruits and ensure that everyone in the family got one. He would eat last. Despite his responsibility of running a big family of over 30 people, he would think of every detail and provide for it, including a proper diet.

Every Sunday evening there would be a cultural program in the family. It was a compulsory gathering, a must for everyone to show their talent. He would give us all different topics and ask us to speak. We would have debates. He would teach us how to speak, correct us wherever we erred and guide us as to how to gather information. We longed for it. We had to be up by 5:30 am every morning. There were no concessions made. I see this particular habit very much lacking in the present generation. It was this discipline of early to rise that gave us the strength and energy for the day.

We all had to sit together for dinner, and recite our prayers before eating. None spoke while eating. We had to judiciously take only as much as we could consume. No one was allowed to waste food. We were unknowingly trained in the discipline of eating all items cooked and served. The thought never crossed our minds in any of us to ask for a different dish. We were not allowed to make any comment about the food. We ate with a smile. This discipline was to show appreciation and save work for the ladies who spent so much time in the kitchen preparing our food. All of us, including grandfather, washed our own plates. If the dining area was not cleared immediately, grandfather would begin cleaning it up himself. After dinner, walking in the backyard was a practice. Grandfather would teach us. He set us on a righteous path by his personal example of simplicity, sacrifice and righteous behavior.

After grandfather died, my uncle became head of the family. I don’t remember even once when he or auntie would show preference to their own children over the rest of us. These are the values that a joint family would inculcate. The girls were married, and many of us went out to work. My elder brother, an eminent doctor, and I joined the army. There was never even a thought of severing the ties. Though physically separated, mentally we were united. When the ancestral property had to be divided, we just left the decision to our uncle. Today that ancestral house accommodates a dance academy run by my daughter. It was my wish to convert it into a temple of learning because it was this house that educated so many of us. I feel content that part of this heritage has passed on to my children and grandchildren. My advice to my children and grandchildren has been to have faith in God at all times and not to be overly excited about their present successes and position.

Even as I reflect upon my childhood and recall my grandfather’s loving care, I rue the attitude of the present generations. Somewhere the parents seemed to have failed in inculcating the disciplines that bring goodness in life. Children of today aspire for liberty of action, and if that is curtailed, they hate it. They have little knowledge of our samskriti, our Hindu culture. If children are brought up without a certain amount of disciplining–by discipline I mean good habits and a sound understanding of the do’s and don’ts, not the cane and anger methods–they are going to be a liability for society. The values the family inculcates in the child are going to decide what kind of a citizen he is going to be. It is the great responsibility of the parents to ensure that they give the country a worthy citizen. If a child does not respect the rules of the house, it is very likely that as an adult he will have little respect for the rules of the land or values of religion. Parents must communicate well with their children and ensure a healthy upbringing with concern for others and the society at large. Our Hindu samskriti is so rich and deep in every aspect. Our ancestors were of superior intellect. They showed us a highly elevated path of life. Let us not stray from that path.

Captain M.S. Srikantaiah, 85, is retired as a career military officer in the Indian army. He fought in the front lines in three wars, including World War II.