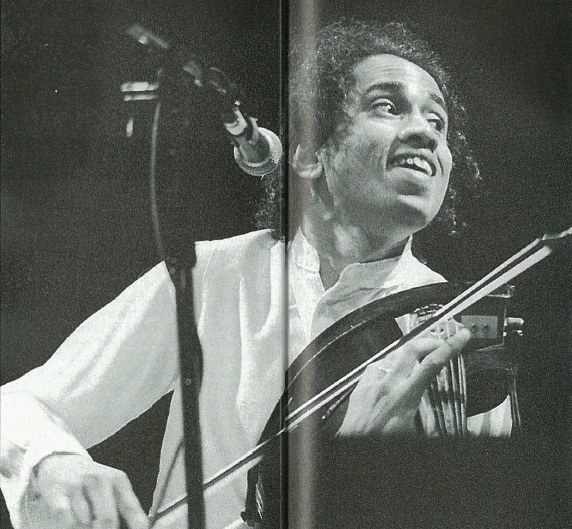

Dr. L. Shankar, an acclaimed virtuoso violinist, singer, composer and producer who has sold over ten million albums, is a musical pioneer. He embraces with equal ease three idioms of music: Indian classical, world music and pop/rock. He has collaborated with a diverse array of musicians, including Ravi Shankar, his brother L. Subramaniyam, his good friend Zakir Hussain, Vikku Vinayakram, Ustad Allauddin Khan, Frank Zappa, Peter Gabriel, Phil Collins, Bruce Springsteen, Van Morrison, Stewart Copeland, Yoko Ono, John Waite, Steve Vai, Ginger Baker, Warren Cuccurullo and Nils Lofgen. With them he has produced dozens of award-winning albums since the early 1970s, featuring some of the most daring, exuberant and technically proficient improvisational music of this decade

By Archana Dongre, Los Angeles

Shankar was a child prodigy. Born in Chennai, he was the youngest of six children in a family completely devoted to music for generations. His father and guru, the late V. Lakshminarayana Iyer, was one of the greatest violinists of his times. His mother Seethalakshmi was a gifted vocalist and played the veena. His brothers Vaidyanathan and Dr. L. Subramaniyam are the legendary violinists based in India and US respectively, and his three sisters are musicians as well.

“My father was very open to all kinds of music and exposed me to various systems–the vast Carnatic and Hindustani systems and other non-Indian arenas as well,” Shankar told Hinduism Today in a recent interview. “My wide interest in music goes back to my childhood years. Teaching me all the time, my father would tell stories about the lives of ancient, great musicians like Tyagaraja.”

Shankar learned vocals from the age of two, violin from age five and played his first concert at seven. He gained considerable reputation in his early youth as an accompanist to some of the most eminent names in Carnatic music, playing all through India.

“I lived in Sri Lanka with my family until the age of eight,” he said. “We left there about 1953. My father was a professor at Jaffna College of Music. He had been there many years. During that time, there were all of these Singhalese and Tamil riots. Since my father was teaching in the college, our house was raided and burned. We lost everything and ran away. Two or three times they tried to kill my father.”

After obtaining a B.S. in physics in India, Shankar came to the US in 1969 and earned a Ph.D. in ethnomusicology from Wesleyan University in Connecticut. But his innovative approach, experimentation and collaboration with Western and world musicians proved more valuable in shaping his unique contribution to the field. “Such experimentation and experience are more in depth than any college, unless you are studying in guru-shishya parampara, on a one-to-one basis,” Shankar said.

His 1980 release of the album Who’s To Know introduced the unique sound of his own invention, the ten-string, stereophonic double violin, to listeners around the world. This instrument, designed by Shankar and built by Ken Parker, covers the entire orchestral range, including double-bass, cello, viola and violin. He has recently developed a newer version of his instrument which is much lighter than the original.

In international concerts, Shankar performs his own compositions, featuring a combination of his haunting vocals and double violin expertise. This has brought him acclaim as an innovator as well as a performer. In his own Indian group, Shankar is accompanied by tabla virtuoso Zakir Hussain and by ghatam [clay pot] instrumentalist Vikku Vinayakram–both giants in the Indian music world. They have released several albums together, including the 1996 Grammy-nominated Raga Aberi. He also co-founded with guitarist John McLaughlin the groundbreaking acoustic group, Shakti, which also features Zakir Hussain and Vinayakram. Shankar’s numerous collaborations with Western musicians have brought him international audiences. He is currently engrossed in four upcoming albums, all part of a project called “Journey Through Life.” His Indian classical album Enlightenment was just released. Shankar will also make an album with Madonna this year. “She is very influenced by Indian classical music and Hindu thought,” he said.

“I am always open to new ideas and experimentation. I am constantly searching for newer horizons involving elements of diverse styles, and my music is so structured that people from a vast variety of backgrounds can understand it and are attracted to it,” Shankar elaborated. “I love children very much. Even in my concerts in India, I address my music to the younger set, so they can develop a liking for it.”

“Indian music is an ancient structure of great musical depth,” he said. “But there are some other great systems in different parts of the world that are good. So I’ve studied the world music, including the Chinese music and Indonesian music and African music, and I’ve worked with a lot of different musicians. Certain things are only possible in certain places. For instance, like making the double violin. It was only possible to have it made in America. Even here they told me at first that it was not possible. But I got some people looking more and more, and finally we did it. Now I have written a lot of new compositions. All my records in the past 20 years have been using new ragas and new talam cycles.”

A favorite cause with him is human rights. “I strongly believe in human rights, and help in any way I can,” he said. He has made many albums for this cause and has worked extensively with Amnesty International, originally through the influence of friend and fellow musician Peter Gabriel, who toured with him on Amnesty tours along with Bruce Springsteen and Sting. These tours also traversed India. “India and Sri Lanka are great, but there are always problems,” Shankar lamented. “But I’m never worried about supporting the right thing. I know there is still a lot of violence in Sri Lanka, and it is very important to have peace. During the tour, they had problems even accepting the idea of human rights. I do what I can from the music side.”

Shankar is enthusiastic about the acceptance of Indian music in the West. He commented with great enthusiasm, “Indian classical is one of the greatest systems of improvisational music in the world. It is very, very sensitive. The ragas can lend such subtle shades. Once the great singer Lou Reed requested the effect of crying in four bars. I thought of some sad ragas and could get the effect he wanted. Our raga and talam systems are so vast and the tonality and rhythm are so intricate that many variations and combinations are possible.”

His concerts the world over earn rave reviews. Yet Shankar humbly wonders if he has a talent. “I just work hard,” he says. “I am a servant of music. My life is for music. I believe in reincarnation. I know we have lived many lives. I believe that I have been a musician in previous lives, and in fact, I really believe that I have played with Zakir.”

Shankar is a man of natural humility. This self-effacement has helped immensely in the development of his musicianship. He explains this in an interestingly personal and practical way: “In my family I was the sixth child. I have three sisters and two brothers, and they are all great musicians, incredibly talented musicians. My father did not have that much time to teach me really. And he was going out a lot, so I just watched all of them. As I grew up like this, I had to really work very, very hard, since I was the youngest one. And I was also the worst one. So I was always very insecure. I kept thinking, ‘I have a long way to go.’ It made me practice extremely hard. I was very lucky to grow up like this, always hearing all of them. Because they were much better than me, I was always hearing and learning something better. I learned a lot from that. In life I have applied this same principle. It has made me stronger, and it has given me patience. Right now I am quite content. But when I came to America I had to start from scratch. I washed dishes, but I didn’t mind. It was like the life of a sannyasin. It was very similar. I was just going from one place to another.”

Shankar respects and admires those who dedicated their lives to music, like Pundit Ravi Shankar and Ustad Allauddin Khan. “These men lived their lives for music,” he says. “But the field of music is getting more commercialized now, and you see younger people who have not sacrificed. All of the great masters of music are dying. Suddenly, there are not too many great musicians left. In those earlier days there were so many.” He feels that the popularity of classical Indian music among young people, which is now on the wane, could come back strongly if they saw performers from their own peer group playing well and with enthusiasm. “Even now, because they see someone closer to their age playing, like Zakir and myself, and especially since we have crossed over to the Western styles, they are coming out to the concerts.” He also laments that television and movies are a problem, pulling people away from the important substance of life. “This really takes away from the life of the kids,” he says. “And the parents are working. Everybody has jobs.”

Shankar enjoys a philosophical approach to music and compares it to life. “You cannot suddenly start praying or playing music when you are 35 years old,” he boldly exclaims. “Certainly, it is never too late to start, but at the same time, it is far better to get going early doing what you are destined to do. We should never be so busy that we cannot pray, dance, write, sing or do whatever we are destined to do. It is very important to get the children involved with something good from a very young age.” And, from his life of music, Shankar shares a final note inspired by austerity and discipline. “We have to correct ourselves,” he says quietly. “I am not trying to be hard on anybody, but I am trying to point out that it is very important to make corrections.”