By Swami Shankarananda

Before my trip to india in 1970, i was an academic in the field of literature. I considered myself the epitome of the Western contemporary man. An “intellectual,” I used my mind fairly effectively, but I had no idea how it worked, nor how to deal with negative emotional states. My intellect was often my friend, but also often my enemy. Seeking a deeper truth, I looked for a teacher. After many adventures, I found him in the siddha master, Swami Muktananda, and spent many years with him. One day, early in my stay with him, I was having a difficult time. He came up to me while I was working in the ashram garden and stood nose to nose, an inch from my face. He whispered the five-syllable mantra Om Namah Sivaya to me. He said, “Repeat this twenty-four hours a day; meditate intensely for four hours a day!” I began the practice, and in less than a day I was experiencing a powerful joy bubbling in my heart.

This was my first experience of the yogic process of introjection, explained by Maharishi Patanjali in his Yoga Sutras (II 33?4), replacing unsuitable thoughts with better ones. Better thoughts include mantras, affirmations like “I am worthy,” mahavakyas or great scriptural statements like “I am That,” and prayer and invocation. The important thing to understand is that the heart of yoga lies in the conscious choice you can make to uplift your mind.

The philosophy of Kashmir Saivism introduces the concept of matrika. A rough modern equivalent for matrika might be “self-talk,” the thoughts we have in our inner consciousness. Some matrika is governed by contracting forces of separation and negation and leads us to states of suffering, while the higher kind of matrika soars with mantric power and connects us to the Divine. A person lost in illusion is tossed up and down on this quixotic stream of matrika, his mind moving in dark habitual spaces, relieved sometimes by a ray of light when things in the world work out briefly. Matrika literally means “the unknown mother.” She is the dark womb of all possible meanings uttering from the depths of consciousness. Only the yogi can become the “Lord of Matrika.” He empowers himself, choosing to move away from contracted negative thought forms that bring fear, anger and sorrow, and towards peace and joy.

The essence of sadhana, or spiritual practice, is to work with your own thought and feeling. The first thing to do is to observe how your mind works. Watch it in action and reaction. Reflect on your own consciousness. This will reveal facts about your inner world that may have escaped your notice. Think of a rock: it sits quietly, fully exhibiting its “rockness” without a doubt or confusion. Even my dog, Bhakti, is certain about who she is and what are her needs. Only a human being comes equipped with a mysterious inner voice that doubts, questions and depresses him. What a wonder! Where does this come from? When our outer enemies revile us, they are nowhere near as effective as our own negative self-talk. I call these negative thoughts of self-attack “tearing thoughts” and “shrinking thoughts,” because they literally tear into our hearts and shrink us from Divinity to diminished personhood. They say, “I am no good.” “That person is better than I am.” “I am stupid.” “No one loves me.” “I am far from God.”

Tearing thoughts are always accompanied by negative feeling. Conversely, the presence of depression and unhappiness sounds the alert: “tearing thoughts in the vicinity!” As yogis, our job is to ferret out these tearing thoughts, look them in the eye and stop believing them. Our goal may be the state beyond the mind, but we live, work and relate in the world of words, and we must learn how to make our way in it.

Negative thoughts create tension within the body. By a disciplined inquiry into these points of tension, they can be released. Such self-inquiry involves an inner search for the sources of our suffering and beyond them to the Self. Where are we holding a wrong understanding? Where are we lacking in faith or operating from fear? Such questions are only for the brave, but eventually we discover that at the very center of our ignorance is the peace and illumination of the Self. Lord Krishna said, “O Arjuna, be a yogi and fight!” To be a yogi means to use our free will again and again, moment to moment. The philosopher Henri Bergson said, “Consciousness wakens as soon as the possibility of choice becomes available.” A Sufi qawaali says: “Choose this or choose that.” The choice is ours–upliftment or despair. A yogi must always choose in the direction of his

Divinity.

Once a seeker was having a difficult time struggling with his ego and his negative matrikas. He went to his guru and asked, “0 Guruji, how can I deal with the negativity of my mind?” The guru said, “You must control your thought. Do not think, ‘I am a sinner,’ don’t even think, ‘I am a King.’ Think: ‘I am Siva, I am the Self, I am Consciousness.’ Keep up such practice and eventually you will be absorbed into Consciousness itself.” In that moment the seeker understood that the heart of the matter is to identify with the highest part of our nature, the Divine, and not the limited ego. Divinity is always at hand, closer than our own heartbeat. Beyond the highest matrika, and flowing directly from it, there is only the silence of the Absolute. The untrammeled heart of Siva is the source and also the destination of all matrika.

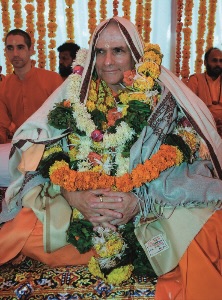

SWAMI SHANKARANANDA,55, heads the Shiva Ashram near Melbourne, Australia. He leads retreats and offers a course introducing the “Shiva Process,” a contemplative tool for living in the world.