By CHQODIE SHIVARAM, BANGALORE

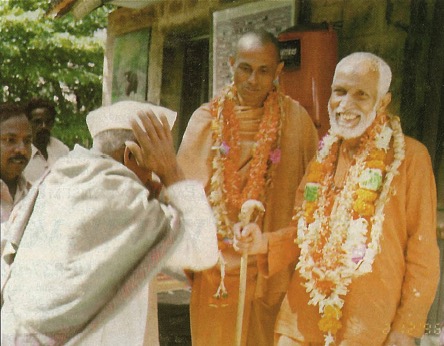

Dear friends,” began Swami Nirmalananda’s short missive of December 23, 1996, “It is with tearful feelings that I bid you farewell. My so-called end is really endless, as there is no end and beginning for life.” Similar letters sent worldwide to 8,000 friends–he called no one his “disciple”–calmly announced the 73-year-old swami’s intent to undergo prayopavesha, self-willed death by fasting. Also called mahaprasthana, “the great departure,” scriptures allow the practice for a terminally-ill ascetic. “My body has become weak,” he explained to Swami Brahmadeva, his designated successor as head of Viswa Shanti Nikethana ashram. “I do not want to be a burden and die in roga (disease), I want to die in yoga. I have discharged all my duties and lived a full life. Now time has come for me to leave.” He planned to accomplish this on January 15, 1997, the auspicious first day of Uttarayana Punyakala in the Hindu calendar.

Swami’s intent had been known for some time, and the local authorities had even posted police at the ashram located in the Balliligiri Rangana Hills (“BR Hills,” 250 km from Bangalore) to prevent what they regarded as an unlawful act of suicide. The police were withdrawn on December 18, and from that day Swami gave up his normal austere diet of hand-pounded wheat bread and jungle greens to take only water. By January 1 he was taking one glass daily. On the 7th, he stopped even that, intending to attain Mahasamadhi on the 15th.

From mid-December a steady stream of visitors came to dissuade Swami. In nearby Mysore and Bangalore, vociferous critics called it all a publicity stunt. On January 10, amidst mounting pressure, the Additional Commissioner of Police, Panduranga Rane, promised action would be taken within two days and Swami Nirmalananda’s rendezvous with prayopavesha would be foiled by hospitalizing and force-feeding him. But Swami was not to be thwarted and breathed his last at 11:45 am that same morning, departing five days earlier than intended.

I arrived at BR Hills on January 11, in time to witness the final stages of the samadhi (burial) ceremony amidst sonorous Vedic hymns. I felt a strange stillness. The atmosphere was neither gloomy nor sad. Thousands of disciples who had rushed to the inaccessible ashram since the news of the death had spread, filed past and silently offered their respects. Most touching was the plight of the Soliga tribals of this hill region for whom Swami was friend, teacher and protector. They sat huddled in the corner, confused, bursting into tears as I spoke to them. They related to me their shock when Swami’s intentions had become clear to them, even though he had consoled each, distributed amongst them clothes and all the money he had and pleaded, “Do not cry when I die–it will be difficult for me in the next world. If you people keep smiling at all times, it will help me reach God, and there I can be here amidst you all.”

Thirty-year-old Jayalaxmi, a Soliga woman, was unconsolable. “I grew up in the ashram since I was a child of five. When I came here last week, Swami gave me clothes to last a whole year and a thousand rupees. He advised me to take care of my home and children, to keep smiling and be always happy,” she sobbed to me. Another said, “We don’t understand all this. We loved and respected Swami. He was our doctor, our guru, our father. We ran to him with any of our problems. We feel orphaned. But we respect his decision.”

Six priests from the historic Srirangapatna temple 100 km away undertook rites for the internment of yogis. The body was bathed in tumeric and sandalwood paste, covered by vibhuti (holy ash) and placed in yogic posture. Then it was lowered into a small cavern which was then filled with 200 kilograms of salt, 15 kilos of camphor and 45 gallons of holy ash. Coincidentally, the sky which was clear all along suddenly clouded and drizzled at the time of final sealing of the samadhi (saint’s tomb). One side of the marker over it had an inscription explaining the meaning of prayopavesha, the other had Swami’s name, date of birth and month and year of attaining Nirvana. The year read 1999. It dawned on me that Nirmalananda, who had decided to live till end of the century, had changed his mind.

A year earlier a Calcutta journalist wrote about Swamiji’s intent. That report did not even cause a flutter. But when Nirmalananda’s missive reached his disciples and they thronged to his ashram, the seriousness of his resolve became clear. Many disciples tried dissuading him. Maria Zilioli from Ireland had arrived on a telepathic call from Swami. “I did not receive his letter, but I could hear him calling me. I’d not seen him for nearly 3 years. Feeling uneasy, I rushed here only to learn that he was on his final journey.”

Dissed by disbelievers: Unsympathetic “rationalists” termed prayopavesha “an act of madness” and labeled Swami a “spiritual pervert.” “A swami who had isolated himself from public life, all of a sudden announces his death, makes it an all-important event and grabs media attention,” accused academician Shri Ramdas. They appealed to the government “to preempt a mentally deranged person.” On the other hand, Swami Paramananda Bharati of Sringeri Mutt affirmed to Hinduism Today that such a death is allowed by scripture for aged ascetics.

Dr. Sudarshan, of Vivekananda Girijana Kendra, the Swami’s neighbor and personal physician, took exception to the rationalists’ outburst, “One might dispute the way Swami chose to leave this world, but it is certainly not an act of madness. He was an intensely spiritual person, and we have to respect his decision. It cannot be termed a suicide, as a yogi can enter prayopavesha. His mind was alert.”

Ramdas countered, “I respect one’s right to live. But there’s no provision to kill oneself in our constitution, whether it’s spiritual or religious. Why have we banned sati [burning of a widow on her husband’s funeral pyre]? It’s nothing but suicide. It’s the business of the state to safeguard every citizen.”

The controversy raged right up to Swami’s last day. The rationalists charged the administration of being soft on the issue. The District Collector, Shri Ajith Seth, called on Swami on January 6 with his father. “He tried to dissuade Swamiji, but in vain. Swami had stopped talking by then and only gave me a written reply in which he said, ‘I’ve given enough to this world and now my body cannot sustain anymore. The call has come from God, and it’s time for me to leave.'” Some of the foreign disciples of Swami had camped at the ashram and stayed by his side day and night till the end came. Their implorations for Swami to eat were in vain.

I visited several colleges in Mysore to ascertain the general reaction to Swami’s actions. Many students and teachers knew Swami, and most objected to his chosen means of death. Among his defenders were Professor Immadi Shiva Basappa, head of the Sanskrit department at the University of Mysore who said, “Prayopavesha is not suicide. Suicide is the result of dejection or disappointment in life. In prayopavesha one gives up his life willingly and happily. It arises out of life fulfillment.” Common was the comment of Vinutha, a final degree student, who said, “Swami Nirmalananda should not have died. It was a kind of selfishness on his part. He should have lived longer. Society today needs more people like him. He was doing so much to protect our forests.”

Choosing death: Swami Nirmalananda suffered severely from chronic asthma, according to Dr. Sudarshan, and was dependent upon inhalers and medication–a dependence Swami did not like. His asthma was expected to worsen, but was not life-threatening. But we don’t know what other health problems Swami might have had.

Prayopavesha, ending one’s life by fasting, is mentioned in ancient scriptures including the Gautama (verse 14.7.12) and Manu Dharma Shastras (verse 6.30). It has been cautiously allowed for ascetics, brahmins and kings. The practice was subject to debate even within the Hindu tradition–Sri Adi Shankara (788-820 ce), for example, opposed it–but it was outlawed only upon the institution of the British Penal Code in India in the 19th century.

Historical examples abound. The Pandava brothers and their wife at the end of the Mahabharata turn over their kingdom to their heirs and walk off to the Himalayas, all except the eldest dying along the way. Other kings have retired to the forest and fasted to death after installing their sons on the throne. “In recent times, Vinod Bhave, Gandhi’s close associate and one-time mentor of Swami Nirmalananda, so passed on. Finding himself in failing health, he stopped taking both food and water and died within a week in November, 1982. Even Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who came to his bedside, was unable to change his mind. The Maharastrian freedom fighter Savarkar similarly died in 1966 at the age of 83. Bhagawan Nityananda, the formidable siddha guru of Swami Muktananda, ceased eating in 1961 and entered Mahasamadhi two months later.

The practice is found among Jain ascetics, who consider it a meritorious passing. In 1987, Jain ascetic Badri Prasad died after fasting more than fifty days. His death, too, was called a suicide, but High Court Justice N.L. Jain told the press that no laws were being broken. “It is in accordance with our religion. There is no pain involved, as the body is in tune with God.”

An aged Aparakarma priest at Nirmalananda’s samadhi ceremonies said, “There’s a world of difference between prayopavesha and suicide. Suicide is a violent form of voluntary sudden death, inflicting pain to the body. It’s born out of dejection and disorientation of mind. It’s escapist in nature. Prayopavesha is a nonviolent, spiritual form of voluntary, slow dissolution of the body. It’s done in quest of communion with Him after fulfilling one’s responsibilities in full. The extinction of life progresses very slowly. To ensure slow, painless and conscious dissolution, the fasting progresses in stages.”

Western scholars, notably Professor Katherine Young of McGill University, Quebec, Canada, have extensively studied the Hindu practice of prayopavesha. They are searching for useful ethical and legal guidelines to resolve the difficult modern issue of care for the terminally ill. The same wisdom which allows an aged and infirm Hindu ascetic to fast to death is being applied to the removal of life support for a patient who will never recover from an incapacitating illness, as well as to the issue of not force feeding an elderly patient who has stopped taking food.

The future of Viswa Shanthi Nikethana is now in the hands of Swami Bramhadeva. He told me, “I have given my word to Swamiji that I shall continue the tradition of rishis and munis and their message to the world. While ordinary people are viewed with two eyes, in today’s situation, the saffron-clad swamis are viewed with 1,000 prying eyes from every angle. An ascetic’s life is like walking on the edge of a sword. We tread this path carefully.

SERVICE, SILENCE, SALVATION

One Swami’s journey from World War II to ashram life

Swami Nirmalananda hailed from the Malabar region in Kerala. Born on December 2, 1924, he discontinued his studies at 14 and left home to join the postal service in the British army. He traveled extensively in Europe while serving in World War II as a noncombatant. Later he visited the USA, Europe, Russia and Japan and seriously pursued philosophy and religion. He came under the spell of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Swami Vivekananda, Mahatma Gandhi, Henry Thoreau, Leo Tolstoy and Albert Schweitzer. He visited over 200 ashrams spread over India. He found, however, that his studies resulted only in mental turmoil and not the Realization he sought. The awakening which finally stilled his turbulent mind occurred not in India, but in Amsterdam, Holland.

Swami had the misfortune to be a mute witness to three major tragedies–World War II, Partition and the Indo-Pakistan conflict. He observed, “If a man turns his attention within, he will be able to see that a constant warfare is going on within his own mind between opposing ideas, urges and desires. It is the sum total of all such conflicts that erupts as open war between nations.”

After taking sannyas, Swami Nirmalananda settled in the serene forests of BR Hills, where he had secured a piece of land in 1964. He became close to the Soliga tribals whom he educated and enlightened on various subjects, while they did whatever work they could at the ashram. Whenever there was a power or water supply problem, delay in postal or transport service to the remote region, Swami set it right for the Soligas with the concerned authorities.

Swami observed mauna, silence, for 11 years. He would not use milk or milk products, tea, coffee, fried or processed food, vegetables and fruits. He lived on the edible wild greens of the forest and bread. He would pound and bake his own whole wheat bread. He always personally cooked and served food to his guests.

Swami Nirmalananda did not believe in rituals. However, he never came in the way of his devotees’ performing pujas at the small temple in the premises of his Vishwa Shanti Nikethana ashram.

Once he said, “The universe needs no correction. God’s world is not mismanaged by Him. First change yourself, then the world around would have already changed for you.”