With Jono Lineen

The tens of millions of Hindus who came to the Kumbha Mela at Haridwar this year were nearly all of modest means. After days of travel, many spent a mere 24 hours in the holy city at the gateway to the Himalayas. They chanted Jai Ganga Ma–“Hail Mother Ganga”–took their sacred bath in the frigid river, collected a pot of holy Ganga water and then headed home. One typical pilgrim, an illiterate woman, traveled with her family by crowded bus from West Bengal, slept in the open and ate at the free feeding tents. “We are poor, but we have enough. I asked God not for money but for peace and salvation”–so easily did this humble villager capture the essence of the world’s greatest act of pilgrimage, the Kumbha Mela.

For her and millions of others, the religious ritual of pilgrimage–one of the five obligatory duties of every Hindu–began with the first plans to attend, and encompasses the entire process of getting ready, freeing oneself from worldly affairs, traveling to the site, taking the bath, meeting the sadhu-mendicants or just observing them from a distance, and the return home. At nearly every mela, pilgrims have been killed in one mishap or another, so each who came duly considered the possibility, however small, that they might not return. For the true devotee, pilgrimage is among the most profound religious practices, one in which material gain–so often the motivation for their prayers at local temples–is superceded by higher aspirations.

The Kumbha Mela takes place every four years in rotation at Haridwar, Prayag (Allahabad), Nasik and Ujjain, according to the placement of Jupiter in the Zodiac. A modern innovation, there are also popular half-melas, ardha-kumbhas, every six years at Haridwar and Prayag. It is at Prayag, where the Yamuna River joins the Ganga, that the largest number of human beings in history gathered–15 million on February 6, 1989. Haridwar, logistically less convenient, managed ten million on April 14, 1998. Still, that’s five times this year’s two million Muslim pilgrims who journeyed to Mecca for the Haj, the second largest gathering.

Every religion, as a matter of doctrine or custom, engages in the practice of pilgrimage to holy places. Among the world’s prime destinations are Bodh Gaya, where Buddha attained enlightenment; Jerusalem, sacred to three religions; Lourdes in France; Amritsar; the Ise Shrine in Japan; and the various Jain sites throughout India.

The Kumbha Mela is unique for its sheer size, and for being a meeting both of ascetics and lay people. Some of the ascetics are naga sadhus, naked monks who practice the severest austerities and leave the mountains and jungles only for the mela. Just the sight of them–and there are thousands–is a blessing to the lay pilgrims.

Within the several-month period of the mela are set auspicious bathing days, usually coinciding with festivals of the period. Most important are the days for the shahisnan, “royal bath,” in which the saints, the naga sadhus first, go in procession to the river.

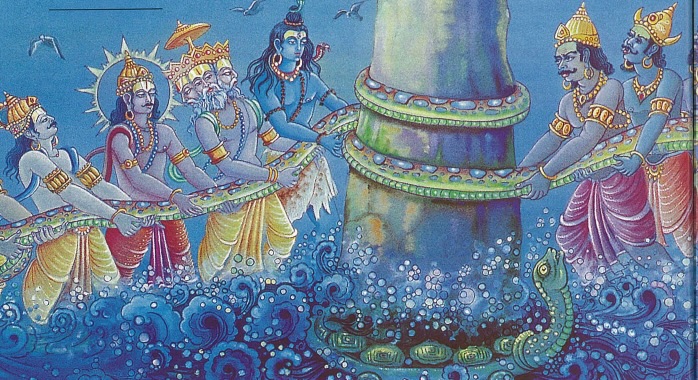

Asked the origin of the event, nearly every pilgrim will narrate the ancient story from the Puranas of the time when the devas (gods or angels) and the asuras (their rivals) cooperated to “churn the Ocean of Milk”–an act which promised to yield countless treasures. With Mount Meru as the post and the serpent Shesha as the churning rope, they set about their task. They agreed to share the most coveted result–the pot (kumbha) of nectar (amrit), by consuming which anyone would become immortal. As they churned mightily, the first substances to be released were deadly fumes and gases. These Lord Siva took upon Himself to consume and neutralize, thus saving the world’s inhabitants from certain death. These poisons turned His throat blue and resulted in His name, Nilakantha. After many aeons of churning, the ocean yielded a series of treasures, the last of which was Dhanvantari, the great healer, who held in his hands the desired chalice of ambrosia.

The asuras immediately demanded their share of the prize, but the devas reneged on their agreement, knowing that if their rivals were to drink the nectar they would be eternally unbeatable, and too great a power to keep in check. The asuras, sensing their position, snatched the kumbha and fled. With the asuras momentarily distracted by Lord Vishnu, the devas retrieved the pot and fled. In their haste they let one drop of nectar fall at Haridwar, Prayag, Ujjain and Nasik.

“Since the beginning,” explains Sri Mahant Rudra Giri Ji, of the Atal Akhara, “the Kumbha Mela was attended by 350 million devas and 88,000 rishis. It was started to promote and propagate our ancient heritage. Even now these devas and rishis participate.” A few of the angelic beings, devas, are able to return with each pilgrim to their home, carried, in a mystical sense, in the pot of Ganga water that each pilgrim collects and places on his home altar. Thus the blessing of the pilgrimage is extended months, even years, beyond the actual event.

Esoterically, it is taught that the kumbha represents higher consciousness, the sahasrara chakra. The amrit that it holds symbolizes mankind’s attainment of that higher reality–the true source of immortality.

According to researcher Subhas Rai, the cosmic alignments associated with the festival are chosen so as to increase the efficacy of the pilgrims’ bathing. He believes the combined power of river Ganga and the auspicious planetary positions generates unique purifying power.

Pilgrimage to sacred rivers is an ancient practice, believed by historian S.B. Roy to exist in India as far back as 10,000 bce. Megasthanes, the 4th century bce Greek visitor to India, described what could have been a Kumbha Mela, but the likeliest first reference is by the Chinese pilgrim Hiuen-Tsang, who resided in India from 629 to 645 ce. He wrote that King Harshavardhan attended, on every fifth year of his reign, a month-long, “ageless festival” at Prayag that attracted up to half a million people from all walks of life.

When references to the Kumbha Mela appear clearly in the 14th century, the mela has all of its modern characteristics–the places, the bathing, the hoards of pilgrims and legions of mendicants. Many believe its organization to be the work of Adi Shankara, the great 8th-century Indian saint, though nothing in his writings supports the assertion. By the 14th century the presence of large numbers of militant sadhu orders was also a clear feature, especially after the wholesale slaughter of Mela pilgrims in 1398 by Muslim general Tirmur, shortly after he leveled Delhi because the reigning sultan was “too tolerant” of Hindus. Similar martial monastic orders have developed in other religions, such as the 12th-century Christian Knights Templar and Hospitalers in Europe–also to protect pilgrims against Muslim oppression–the Shao Lin monks of Kung Fu martial arts fame in China, the Buddhist monastic police of Tibet and the Zen master archers and swordsmen of Japan. Sadly, through the centuries mendicant militancy has led to frequent murderous Kumbha Mela battles over who gets to bathe closest to the supremely auspicious moment–the very issue which caused this year’s fight.

Many orders of sadhus gather at the Mela. A large portion are members of a dozen or more orders called akharas, the most prominent being the Juna and Niranjani–the two who tangled this year. Others include the Agan, Alakhiya, Abhana, Anand, Mahanirvani and Atal. Most orders are Saivite, three are Vaishnavite and a few are Sikh orders patterned after the Hindu monastic system. Akhara is Hindi for a “wrestling arena,” and can mean either a place of verbal debate, or one of real fighting. Each akhara may contain monks of several different Dasanami orders–the ten designations–Saraswati, Puri, Bana, Tirtha, Giri, Parvati, Bharati, Aranya, Ashrama, and Sagara–regularized by Adi Shankara in the 8th century. Thus, the akharas overlap with the Dasanami system. There are also sannyasi orders, such as the Nathas, that exist outside the Dasanami system. The akharas’ dates of founding range from the sixth to the fourteenth century. The development of the akharas and the Kumbha Mela took place over the same time span and are likely related. Akharas may include thousands, even tens of thousands, of sadhus. Several akharas run hundreds of ashrams, schools and service institutions.

The Kumbha Mela is a time to elect new akhara leadership, discuss and solve problems, consult with the other akharas, meet with devotees and initiate new monastics. During Muslim and British times, the mela gathering of pilgrims and sadhus was a significant force in the preservation of Hinduism and the continued identity of India as a Hindu nation. “Khumba weaves our nation into one,” said Mahant Ganga Puri of the Mahanirvani Akhara.

One little-known purpose of the Mela is to review smriti, the codes (shastras) of law and conduct which govern Hindu society. Unlike the Vedas and other revealed scriptures, these codes are meant to be adjusted according to changes in time and circumstance. Ramesh Bhai Oza explained, “The saints from all over India should get together at the Mela to discuss not only religious and spiritual matters, but also the problems faced by the contemporary society. Their solutions offer a new system and a new smriti.” Ramesh is a world renowned performer of kathak (preaching through song and sermon on the life of Lord Rama and other Hindu heros).

Many are the motivations and benefits for Hindus to attend the Kumbha Mela, the most popular pilgrimage of the day. It is a time to gain a new look on life, to purify oneself and to regain the sense of Godly aspiration as the central purpose for this earthly incarnation.

TIME LINE

10,000 bce: Historian S.B. Roy postulates presence of ritual bathing.

600 bce: River melas are mentioned in Buddhist writings.

400 bce: Greek ambassador to Indian King Chandra Gupta reports on a mela.

ca 300 ce: Roy believes present form of melas crystallizes. Various Puranas, written texts based on oral traditions of unknown antiquity, recount the dropping of the nectar of immortality at four sites after the “churning of the ocean.”

547: Earliest founding date of an akhara,

the Abhana.

600: Chinese pilgrim Hiuen-Tsang attends mela at Prayag (modern Allahabad) organized by King Harsha on a five-year cycle.

ca 800: Adi Shankara believed to have reorganized and promoted kumbha melas.

904: Founding of Niranjani Akhara

1146: Founding of Juna Akhara

1300: Kanphata Yogi militant ascetics employed in army of King of Kanaj, Rajasthan

1398: Tirmur lays waste to Delhi to punish Sultan’s tolerance toward Hindus, proceeds to Haridwar mela and massacres thousands. Hindu ascetics arm themselves.

1565: Madhusudana Sarasvati organizes fighting units of Dasanami orders.

1684: French traveller Tavernier estimates 1.2 million Hindu ascetics in India.

1760: Saivites battle with Vaishnava sects at Haridwar; 1,800 are killed.

ca 1780: British establish the order for royal bathing by the monastic groups (the same order is followed today).

1820: Stampede leaves 430 dead at Haridwar mela.

1906: British calvary intercede in mela battle between sadhus.

1954: Four million people, one percent of India’s population, attend mela at Allahabad, hundreds perish in a stampede.

1986: Most recent Haridwar mela.

1989: Guinness Book of World Records proclaims 15-million-strong mela crowd at Allahabad on February 6 “the largest-ever gathering of human beings for a single purpose.”

1992: Most recent mela at Ujjain and Nasik

1995: “Half-mela” (at six-year interval) at Allahabad has 20 million pilgrims by official estimates on January 30 bathing day.

1998: Haridwar Mela attracts 25 million pilgrims in four months, ten million on April 14.

2001: Next mela at Allahabad

2003: Next mela at Nasik

2004: Next mela at Ujjain

2010: Next mela at Haridwar