Rajeev and Rajeevan take opposite sides on a contentious issue now in the fore in India

There is no doubt that buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism are all Indic religions, along with Hinduism. There are commonalities between Indic religions; thus you can posit a family resemblance among them.

No Sikh would dispute the fact that his religion is Indic, heir to the genius of the Indus-Sarasvati civilization, possibly the earliest great civilization in the world. The Indic religions generally share the following beliefs: the universe is cyclical; the goal of man is to gain salvation through following the path of good; ultimate evil does not exist; man’s plight is only due to the soul’s immaturity. They are generally tolerant and broad-minded.

Sikhism believes in all these. But the Sikh protests when people label his religion as part of Hinduism. There is merit to this position–Sikhism is a distinct Indic religion.

Hinduism is extremely eclectic, and has the proven ability to absorb and nurture many schools of thought, including those that are fundamentally opposed to each other. For instance, there are ecstatically devout bhakti sects and, at the other extreme, determinedly materialistic Charvakas.

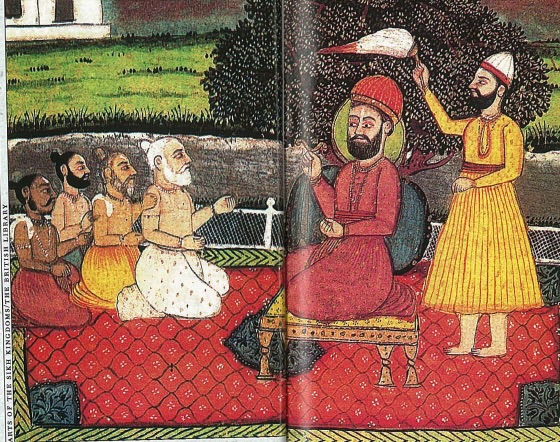

Perhaps this very eclecticism of Hinduism worries some Sikhs, who fear that without a distinct identity, their religion will, over time, become just another sect in Hinduism. This has led some Sikhs to emphasize their differences with Hinduism and to idealize the distinctive turban, unshorn hair/beard, sword, white dress, iron bracelet and comb of the believing Sikh.

What, indeed, are the key differences with Hinduism? Sikhs do not practice caste; they do not believe in the celibate and ascetic way of life; they do not bow to the authority of the Vedas; they do not venerate idols; they are monotheistic. Doctrinally, they believe in the Adi Granth Sahib as God’s revelation, they believe in the line of ten Sikh gurus as the true teachers of their faith and they do not believe in ahimsa, nonviolence. The Sikh insistence of not venerating idols derives undoubtedly from the Islamic influence on the founders of the faith.

The doctrinal differences are intriguing. The Sikh belief in the Adi Granth is like the Semitic belief in holy books. The Granth is venerated with the same intensity that a Hindu applies to his images. The message of the Granth is robust and practical, that a man grows spiritually by living truthfully, serving selflessly and by repetition of the Holy Name (Sat Nam) and Guru Nanak’s prayer, Japaji. “Sat Sri Akal,” they say, “God is Truth.”

The Adi Granth does not seek answers to the philosophical questions of the universe as the Hindu scriptures do. It is, instead, more concerned with the practical questions of living the true life: salvation lies in understanding the divine Truth, and man’s surest path lies in faith, love, purity and devotion. The Granth is strong on the bhakti and particularly on the karma paths. It stresses devotion and action over philosophical speculation or meditation.

The Sikhs believe in their ten gurus. A guru is an essential guide who helps awaken a soul to its true nature. The guru lineage starts with Guru Nanak and ends with Guru Tegh Bahadur–and there can be no more. Sikhs do not, however, recognize a priestly class, per se. In fact they reject the caste system. The last major doctrinal difference between mainstream Hinduism and Sikhism is the explicit rejection by the latter of nonviolence, vegetarianism, celibacy and asceticism, all of which are Hindu ideals.

Unlike Hinduism where the separation of church and state is total, Sikhism has a strong temporal component. This was born out of necessity, as Sikhs, especially during Mughal rule, were the defenders of the land and the people against royal excesses. This martial tradition continues to this day, and Sikhs are universally recognized for their valor.

The sturdy and vigorous values of Sikhs also show in their tradition of community service. In their langars they feed the indigent. You will never find a Sikh begging. They are disproportionately represented in the armed forces, serving their country. Their earthy good sense and hard work have made them prosperous farmers, industrialists, and, oddly enough, pop musicians!

It is unfair to characterize these determinedly practical people as part of the other-worldly and mystical Hindu tradition, especially if they don’t want to be so identified. Although it is clear that Sikhism arose as one of the reformations of Hinduism, today they stand as a full and separate religion.

Rajeev Srinivasan is a devout Hindu. After many years in the US, he now lives in India. He writes a regular column on www.rediff.com.– rajeevmail@yahoo.com

YES! WE ARE ONE GREAT RELIGIOUS TRADITION

By Rajeevan Kattil, Detroit, Michigan, USA

We need to establish a catechism for being a Hindu to examine who is a Hindu and who is not: What causes others to call us Hindus? What critical spiritual beliefs differentiate us from the rest? To answer this question, we must look at origins of world religions. Most of today’s world’s religions arose from two ancient traditions: the Indus Valley tradition and the Israeli tradition. Many other ancient religions have died out, including the Egyptian, Roman and Greek.

The Israeli tradition is the root of three religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Central to this tradition is the belief of an all-powerful God. The Semitic God is not bound by any laws. He created the world and all the creatures, including human beings. We get one shot at life; no second chances. After death, our souls rest in the twilight world until the day of judgment, when they will either be sent to heaven or hell.

Contrast this with the Indus Valley tradition, which is the basis for a great many of the Eastern religions. All living beings have a soul. Most souls are reborn as other beings after their death. The objective is to break the cycle of death and rebirth, which alone removes the circle of sorrow. God, or Supreme Being, is not an autocratic policeman. He creates and abides within dharma, the laws of the universe. Once the soul breaks the cycle of rebirth, it becomes one with the indeterminate spirit of the universe.

Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs all believe in this tradition. They may call it different names, but the concept is the same–e.g., Hindus refer to the ultimate realization as Moksha, while Buddhists and Sikhs call it Nirvana. Hinduism provides multiple avenues for our journey to Moksha: bhakti (worship), karma (righteous action), jnana (pursuit of knowledge) and yoga or tapas (austerity). Buddhists, Jains and Sikhs have all kept this belief in multiple paths. Sikhs in particular believe in a combination of worship and meditation.

The Advaita philosophy in the Hindu tradition talks about Saguna Brahman (God with properties), and Nirguna Brahman (God without properties), two views of the same essential reality. Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, talks of the divine being as both sakar and nirakar, with form and formless–not at all different from the Hindu concept.

Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism are all subsets of Hinduism–they all share the central faiths of Hinduism. All were born out of their founders’ desire to combat perceived ills of Hinduism, mainly the caste system, brahmin domination and over reliance on brahminic rituals. In the classical sense, all can be termed reformation movements, akin to the Christian Reformation which sought to bring religion back to the common people.

Today there are a great many denominations of Christianity–Catholic, Methodist, Presbyterian. In the Christian majority USA where I live, people commonly ask each other, “What is your religion?” and answer “Southern Baptist,” or “Mormon,” etc. Yet collectively, all of these are considered one religion: Christianity. Never mind that the Mormons believe not only in Jesus Christ, but other saints unique to their tradition. They are considered Christians as well.

Why do we refer to Mormons as Christians? Is it because they claim so, or is it because the majority of non-Mormons think they are Christians? The answer, I believe, is a little of both. It is not just religions that have these nicknames or groupings imposed on them. India is called as such because of Western references to this name. All people outside “Deutchland” know it as Germany.

If a group of people want to declare themselves as Sikhs and non-Hindus, they certainly have a right do so. However, their right to this self-classification does not negate everyone else’s right to sociologically classify them using the most fitting definitions. The minority rights in the Indian constitution are a sociological attempt to correct the ills of the past and must, therefore, use sociological definitions, not self-definitions from a particular community.In the sociological context, I do believe Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains are all Hindus, sharing portions of a common culture, history mythology and beliefs. The differences between these religions are similar to the differences among Christian denominations.

Rajeevan Kattil is computer systems analyst in Detroit, Michigan, USA. He is helping renovate a temple near his Kerala home.rkattil@ aol.com