Nepal’s chief surveyor recounts the Himalayas’ spiritual importance, the modern and ancient history and his own 2019 work on Everest’s summit

By Khim Lal Gautam with Madhu Sudan Adhikari, Nepal

The Himalayan mountains form a 1,500-mile arc from Naga Parbat in Pakistan to Namchabarwa in Tibet, crossing India, Nepal and Bhutan. Three of the world’s greatest rivers, the Indus, Ganga and Brahmaputra, originate in the Himalayas—literally “the abode of snow”—providing fresh water to more than 700 million people. The range has numerous high peaks, including the world’s highest, Everest, or in Hindu lore, Naubandhana, which when covered with shining snow looks like the crown of the Earth.

Here modern researchers of various disciplines find much to study: geography, geology, hydrology, meteorology, biodiversity, ecology, environment, sociology, ethnicity, art, culture and more. It is the most appropriate place for adventurous tourists to hike, explore deep canyons or climb mountains. It is a huge store of natural resources. Small wonder that people since time immemorial have been so keen to know about this versatile and precious natural gift—seeking to understand how the mountains were formed, how high the peaks are and how they might be climbed.

The Himalayas in Scripture

We can find several modern and ancient literatures that exalt and explain the glory of the Himalayas. Ancient literature mentioning them include three great Sanskrit poems: Kumarasambhava of Kalidasa, Kiratarjuniya of Bharabi and Naisadacharita of Sriharsha. In the very first sloka of Kumarasambhava, Kalidasa describes the Himalayas: “There is to the north a mountain named Himalaya, whose soul is Deity, with his spurs diving into the Eastern and Western ocean; he stands as the measuring rod of the earth.” In sloka 1.17, he wrote, “And marking him as the source of the materials of sacrifice, and marking him strength, as well able to support the earth, the Creator bade him share in the sacrifice, and Himself attended his installation as king of the mountains.”

In 5.10 of the Kiratarjuniya, Bharabi explains the range’s richness: “The Himalaya bears no mountain peaks without heaps of gems, no caves without creepers; the Himalayan rivers that look like the newly married bride are full of the lotus, and there is no tree in the region without flowers.”

In Naisadacharita, sloka 19.32, the beauty of the Himalayan rocks is described: “Should not the beds of the day lotus laugh, the sun, their ally, being up? Should not the night lotus slumber, the moon, its friend, having lost its radiance? Perhaps the day lotus blossoms have exchanged their sleep for yonder smile of the night lotus bed; the smile that resembles the Himalayan rocks in beauty.”

One can find several analogical expressions regarding Himalaya in other Sanskrit texts, such as 10.25 of the Bhagavad Gita where Krishna says, “I am Bhrigu amongst the great seers and the transcendental Om amongst sounds. Amongst chants know Me to be the repetition of the Holy Name; amongst immovable things, I am the Himalayas.”

The Rigveda, oldest of the Vedic texts, in sloka 10.121.4 says that the Himalayas, the oceans, and the universe all are created by the Almighty. “Through His might, are these snow-covered mountains, and what men call the sea and Earth His possession: His arms are these, His are these heavenly regions.”

The History of Everest Research

Mount Everest was a lesser-known mountain until the British embarked on their long-term mission to colonize South Asian countries. The East India Company undertook The Great Trigonometric Survey of India in 1802 under the direction of William Lambton, to precisely survey the entire Indian subcontinent. Beginning in the South and working at times with 700 people and huge instruments, they established with great accuracy the latitude and longitude of survey towers and stone markers at points across India.

In 1823 George Everest (he pronounced his name “eave-rest,” incidentally) took over the survey and reached North India. At the time, Dhaulagiri (214 miles to the west) was thought to be the highest peak in the world. As the survey team established control points to measure the Himalayas, they eventually identified one mountain, “Peak XV,” as the highest, at 29,000 feet. Concerned that all the zeroes might give the impression that the elevation was rounded off, the lead surveyor added two feet to make it sound more exact: 29,002. According to a long-standing joke, he thus became the first person to put “two feet” on the mountain. In 1865, the Royal Geographical Society named it after Everest (over his objections). Thereafter, Sagarmatha (its Nepali name) earned global fame as Mount Everest.

Geologists say the Himalayan range began to form 40 to 50 million years ago, when two large landmasses, India and Eurasia, driven by plate movement, collided. Because both landmasses have about the same rock density, one plate could not be subducted under the other; the pressure of the impinging plates could only be relieved by thrusting skyward, which contorted the collision zone and formed the jagged Himalayan peaks. What had been the bottom of the Tethys Sea became the world’s tallest realm.

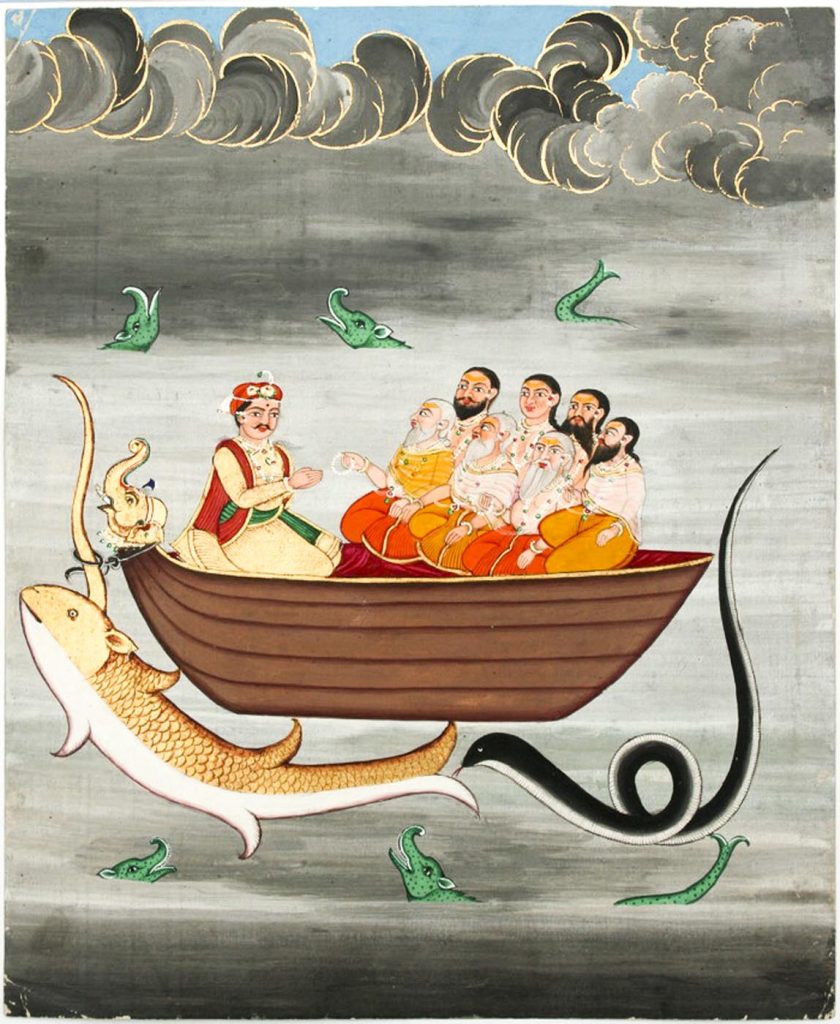

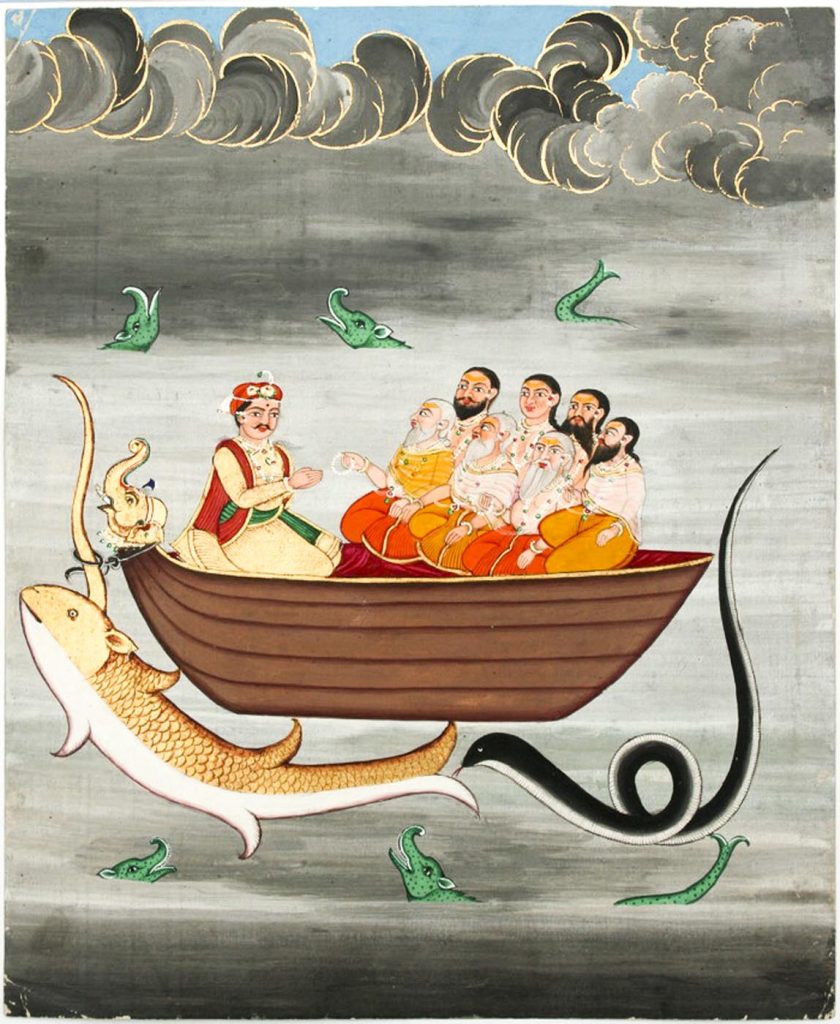

In the Great Flood

Many peaks are sacred in both Hinduism and Buddhism, but Mt. Everest has a special place in Hindu scripture. According to a story in the Matsya Purana, by the end of the Chakshusha Manu era, when the king was offering water to the Sun in the Kritmala river, a small fish came in his hands. When Satyavrat tried to put the fish back in the river, the fish asked not to put there but to be saved. The king brought him to the ashram in his water pot. The fish grew larger overnight, and the king put him in a bigger pot. The fish again grew in the pot, and the king put him in a pond. The fish quickly grew even there. Realizing this was no ordinary fish, Satyavrat set out to throw it into the sea. But again the fish asked not to be released, but to be saved. With folded hands, the king spoke to the fish, saying he seemed to be no ordinary fish and asked of its real nature .

Then Lord Vishnu appeared in the form of His fish avatar and explained soon the earth would be submerged in the sea due to a catastrophe of excessive rain. “In advance, with my inspiration, you will make a huge boat. When the catastrophe starts, you will take all living beings into the boat, including the seven sages, and seeds from all the Earth’s plants. I will come to you in this horned fish form. Tie your boat to my horn with the serpent Vasuki and I will pull you safely through the sea.” Saying this, Vishnu disappeared.

The king started doing penance, the catastrophic rains arrived. The monarch sat in the great boat with the sages, food, animals and seeds, and the sea began to rise. Vishnu’s fish avatar, Matsya, appeared and the king tied the boat to His horn. While navigating the waters, Matsya taught the king the principle of Self, then secured their safety by tying the boat to a lofty Himalayan peak. Thus ended the sixth Manu era, Chakahusha, and began the seventh, Vaivasvata.

The tip of the Himalaya that remained above water while the remainder earth was submerged was obviously the tallest peak of the world, Everest. The line where the boat was tied is still there on the mountain as a yellow band below the summit at 29,032 feet—well above the second highest mountain, K2 at 28,251 feet. Thus without measuring its height, the highest peak of the world was identified at the beginning of Earth’s present era, Vaivasvata Manu. The peak was named at that time as Naubandhana (nau = boat; bandha = tie).

We can find these slokas in Mahabharata: “O best of the Bharatas! She was immediately bound there by the sages. Hearing the words of the fish, the boat reached the peak of the Himalayas. That is the peak called Naubandhana, beyond the Himalayas. It is still well known. O, Arjuna! O, best of the Bharatas! know this fact.”

From the above, we can say that Mt. Everest was in existence at least at the end of the sixth era of Manu. To determine that date, we can then calculate backwards from chants at the commencement of Hindu rituals, which state we are “in the second half of Brahma’s life, in His very first day, Svetabarahkalpa, in the Vaivasvata Manvantara, in the 28th yuga, in the 5,123rd year [in 2022 ce] of the Kali Yuga.” From this, I have determined that the tying of the boat to Everest took place 122,261,123 years ago. This is earlier than the geologists’ 40 to 50 million years for the origin of the mountains, but not totally out of line, especially when compared to the Biblical date for the similar story of a great flood and Noah’s ark being set in time at just 4,372 years ago!

One can’t determine from our scriptures, however, when the Himalayas were created. The first mention is Rigveda 10.121.4 which says they were created by God. There was no issue of climbing the Himalayas, because the Deities used to go there for penance and meditation.

No measurement was made to find the highest peak, because the only peak that was not submerged during the catastrophic flood was the highest one, Naukabandhan.

It is, of course, difficult to verify the above dating calculations, but as a surveyor, I found it a most interesting exercise in exploring our geographical history as portrayed in our scriptures. But a catastrophic earthquake in Nepal brought Everest into my life and work in a very real manner.

When the Earthquake Struck

It was Saturday noon, 25 April, 2015. I was fitting a solar panel at our newly rented office building in Sirdibas village of Gorkha, a district in the foothills of Himalayas around 56 miles northwest of Kathmandu. Flocks of birds fluttered over me, and dogs started barking loudly. All of a sudden, I felt a tremor underfoot. The intensity of the jolt continued worsening for a couple of minutes. A building 165 feet away was destroyed right before my eyes. People were crying in panic as they ran out of their houses to open spaces.

My building was trembling so badly that I was really scared, my mind almost frozen in fear. I had absolutely no idea what was going on. I don’t know exactly what I was thinking, but I jumped off the 25-foot-tall building—somehow without hurting myself—and ran towards an open space where people were shouting, “Earthquake, earthquake!” Only then did I realize what was happening.

We later heard on the radio that the epicenter of the 7.8 Richter scale earthquake was Barpak, a village just 12 miles away from us. Thousands of houses as well as cultural monuments in our area were reduced to rubble.

Did Everest Gain Elevation?

Scientists and researchers from around the world talked about a possible change in the height of Nepal’s mountains due to the earthquake. It was determined that Kathmandu Valley itself had moved 4.7 feet to the southwest and was uplifted three feet. Responding to widespread questions over the height of Mount Everest, the survey department announced that a new measurement would be made with its own resources and manpower. A team of 80 surveyors led by Deputy Director General Susheel Dangol was assigned to accomplish the overall campaign. Different groups were formed for different tasks. It was my great good fortune to be assigned with the most important and challenging task, the leader of Summit Observation. Perhaps, I got that opportunity because I had previously summited Everest in 2011.

Our team arrived at Everest base camp in April, 2019, for 26 days of acclimatization. On May 18th, surveyor Rabin Karki and I headed up the Kumbhu Icefall with three sherpas, while two of our surveyors, Yubaraj Dhital and Suraj Singh Bhandari, stayed at base camp. Our team carried survey instruments to conduct observations using the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS). In conjunction with observations by several other teams, these would pinpoint accurately the elevation of the highest point on Earth.

We reached Camp II the same day, Camp III at the base of Lhotse Face the next day, and Camp IV at the South Col the next. That is easy to say, but this was technical climbing at high altitude, with hurricane force winds at the South Col. But that was the least of our worries. When we got to Camp IV, we learned that the stockpile of oxygen that was supposed to be there had not yet arrived. The situation was critical: without oxygen, it is nearly impossible to summit, and a return to base camp basically means going home. Fortunately, we successfully borrowed enough for our purposes.

We headed for the summit at 2 pm, putting us there around midnight. This was unusual, as most climbers start from the saddle at about midnight and take 10-15 hours to reach the top. Our guides were concerned: “If it is too cold, we cannot even take off our mittens to work with the equipment.”

But the nighttime arrival also meant our work would not be disturbed by a rush of climbers on the summit. Additionally, satellite positioning data is much more accurate if it is made at night instead of at sunrise. This expedition was all about accuracy, and we had to do everything in our power to ensure that there would be no margin for error in our measurements.

We reached the summit at 3am on May 22. Unlike my first climb, it was pitch dark, very windy, and I was utterly exhausted after 13 straight hours of trudging up the mountain. I had nothing left in me physically, and just thinking about the descent made me nervous. But there was no time to think about anything. There was work to be done. Despite the extreme tiredness, howling wind and numbing cold, we had to complete our GNSS survey and the Ground Penetrating Radar observation (to measure the depth of snow under us)—all in the limited time window at our disposal. We were completely focused on our work, which we had rehearsed many times at base camp.

We stayed on the summit for almost two hours, installing the GNSS equipment on a small, sturdy tripod designed especially to work on the summit. By 4 am, as the eastern sky started lighting up, other climbers began to arrive at the summit. I was now worried that the climbers would affect the sensitive data we were collecting. However, members of our team kept the climbers from going near the GNSS antenna at the top. Finished with our data collection, we headed back down, contending with a throng of climbers ascending—a record 223 in a single day. At the Hillary Step, we had to wait two hours for our turn on the one-way route.

While we were descending from the South Summit at about 28,000 feet, Rabin Karki’s oxygen system started giving him trouble. His life was at risk. Our guide Tshiring Jangbu Sherpa borrowed an extra oxygen cylinder from another Sherpa colleague, and Rabin managed to continue his descent.

I was drained, and did not have much energy left by the time we got back down to the Balcony. My condition got worse, and on the slope down to the South Col at one point I actually lost consciousness at 26,903—700 feet above the start of the “death zone.” The rest of my team were ahead of me and did not realize I had fallen. I must have lain there for two hours in the blue ice, until another climber kicked me to see if I was alive. Normally, if climbers fall unconscious at that altitude, it is unlikely that they will wake up again. It was that kick, and a miracle, that woke me up so that I could stumble down the mountain that day, with the precious cargo of data in my backpack.

Conclusion

Though as per the Hindu mythology it was known 120 million years ago as the highest peak of the world with a different name, Naubandhan, our mission on measuring Sagarmatha (as we Nepalese call Mt. Everest) was successful in gathering all data required for the measurement. In 2020, Nepal and China—based on the findings of their independent survey announced 29,031.69 feet (8,848.86 meters) as the new official height of Mount Everest. That is three feet higher than any previous measurement, a difference largely attributed to the earthquake. It was the most accurate measurement ever made of Sagarmatha and a historic event, not just for Nepal but also for the rest of the world. Our detailed report is here: bit.ly/KhimlalEverest.

Trigonometry’s True Origins

By Khim Lal Gautam

Even today, surveying is largely based on trigonometry, the branch of mathematics dealing with triangles. In Hindu tradition, this comes under one of the six vedangas or subject sections of the Vedas, specifically astrology, which includes both observation of the stars and of terrestrial geography.

In the West, it is taught that Pythagoras, born in 570 bce, is the founder of trigonometry and the discoverer of the theorem named after him. But research has found that the Pythagorean theorem was already described in the Sulbasutra, one of six important books written by Baudhayana around 800 bce. Baudhayana did not just explain the relation of sides and hypotenuse of isosceles triangles (the famed a2+b2= c2); he explained various relationships between the area and the diagonal and the remaining sides of rectangles.

For example, sutra 48: “If a rope is stretched along the diagonal length [of a rectangle], the resulting area [of a square with sides of that length] will be equal to the sum total of the area [meaning squares] of horizontal and vertical sides taken together.” Put in simpler language, if one takes the diagonal of a rectangle and creates a square of that height and width, its area will be equal to squares created by the length of the horizontal and vertical sides. In other words, the square of the diagonal is equal to the sum of the squares of the two sides. This is exactly Pythagorus’ theorem, which came two centuries later.

Much later in history, the mathematician Bhaskaracharya, born in 1114ce, developed methods to measure the height of an object from a distance. He was first famous for the Siddhanta Shiromani, which he wrote at the age of 36. This text elaborated the construction of nine ingenious instruments which help observe the stars and calculate the time. One, the Yasti Yantra or stick machine, could measure the height of objects without knowing their distance, (but there seems to have been no systematic effort to measure the heights of mountains).

Though it is still commonly believed that the basis of the mathematics of modern survey science is the theorem ascribed to Pythagoras, all its elements were already articulated in Hindu literature at least 250 years before him. Our scriptures were rich not only in their spiritual teachings and history, but also in science and technology.

About the Author

Khim Lal Gautam is the Chief Survey Officer at Nepal’s Survey Department. He wrote Pandhraun Chuli (Peak XV), a book on Everest measurement and expedition, in Nepalese. He was born in the Hadaule Village of Kaski District. He has completed his Masters in Geographical Information Science and Systems from Universität Salzburg in Austria. Since childhood, Gautam has been enamored with the Himalayas. Madhusudhan Adhikari is a former secretary and former director general of Nepal’s Survey Department. email: gautamkhimlal@gmail.com