For these eight composers, music was a spiritual path, an ascent to higher consciousness and moksha

By Lakshmi Chandrashekar Subramanian; art by Baani Sekhon

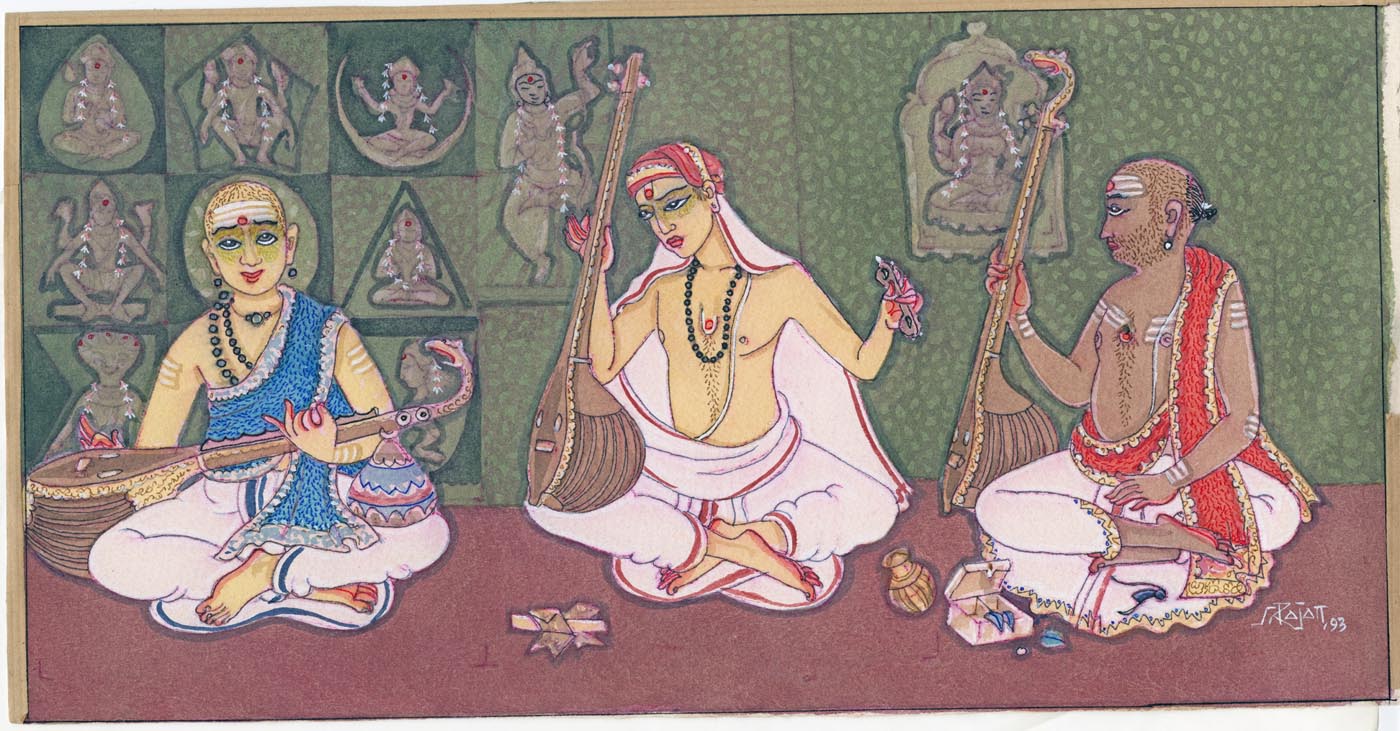

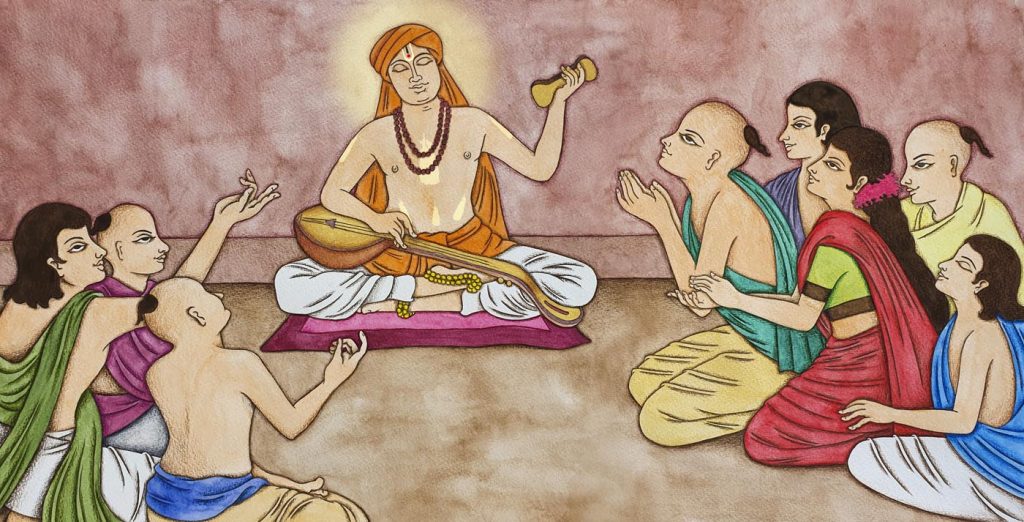

Aradhana refers to glorifying and paying homage, and this Educational Insight is just that. It is a homage to the immortal musical and spiritual giants of the Carnatic music tradition. “Endaro Mahanubhavulu,” sings Tyagaraja, as he offers salutations to the many saints who have lived through the ages. With a similar sentiment of awe and admiration, we explore the lives and songs of eight Carnatic composer-saints. A classical South Indian art form dating back to ancient times, Carnatic music originated as a devotional language. Each of these composers was devoted to Deities who abundantly inspired their spiritual and creative minds. They were vessels of overflowing bhakti, musical creativity and scholarship, easily communicating the inherent relationship between Advaita philosophy and theistic worship.

Carnatic music weds the melodic (raga) with the rhythmic (tala), binding devotional expression with technical improvisations. These virtuosic composer-saints were powerhouses of musical and scriptural knowledge—voices of raga, swara (musical notes), sahitya (lyrics) and Vedanta. Music was their way of life, a vehicle to the Divine—not only to the Divine almighty, but to their inner divinity. They reached tremendous spiritual heights through their outpourings of love, loyalty, seeking and surrender.

Carnatic music connects all the states of South India. These composers brought out the beautiful nuances of Indian languages in their compositions, whether in Sanskrit, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam or Tamil. Deep philosophical truths from the Itihasas, Puranas, Vedas, Vedanta and Brahmasutras permeate each song, and the composers sing about topics that have practical relevance in our lives today. When we listen to the devoted offerings of Shyama Shastri, we wonder how we can develop surrender to Goddess Bangaru Kamakshi; when we hear the kritis of Sadasiva Brahmendra we, too, ponder the true purpose of our lives.

The 15th through 19th century was a golden period of 500 years for Carnatic music, immeasurably contributing to the bhakti movements of India. Numerous composers were prolific, producing a staggering volume and variety of work. Sri Tallapakka Annamacharya worshiped the God of Tirumala, Lord Venkateshwara, with his sankirtanas in early 15th century Andhra Pradesh. In the same century, Sangita Pitamaha Saint Purandaradasa sang soulful Devaranamas. Sadasiva Brahmendra and Oothukkadu Venkata Kavi created Sanskrit masterpieces in the 18th century. The Carnatic music trinity (Sangita Trimurti) Sri Shyama Shastri, Sri Tyagaraja and Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar were all born in the temple town of Thiruvarur, a religious and cultural haven in Tamil Nadu, within a short period of fourteen years. Kerala’s shining star, Maharaja Swati Tirunal, composed songs for Lord Padmanabhaswami in the 19th century.

These saints were Vaggeyakaras, composing lyrics (sahitya) as well as music for their visionary compositions. They developed compositional styles that brought out the depth and beauty of every raga, and adopted the kriti as their primary mode of expression. They are not only renowned within the field of Carnatic music, but stand among the greatest musical giants to have ever lived.

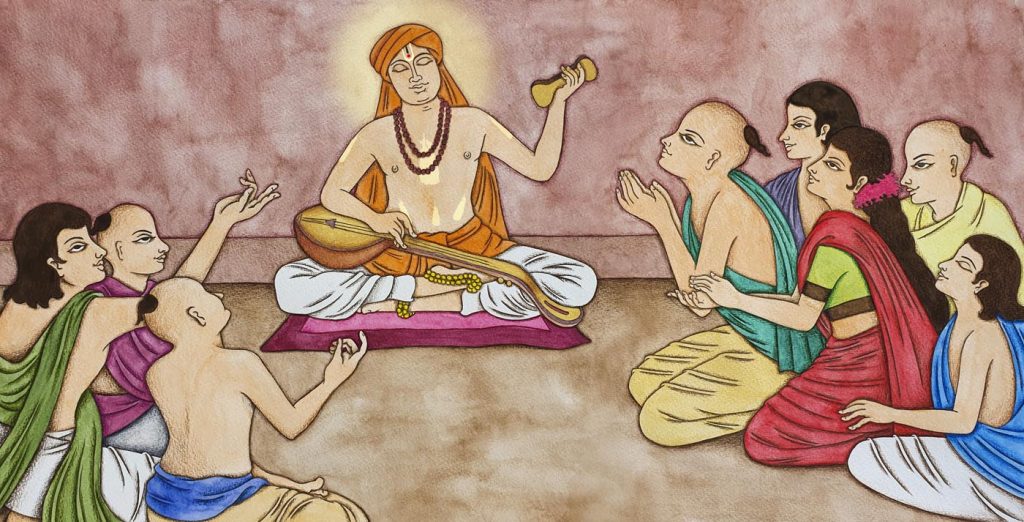

During a time when Carnatic music flourished in temples and royal courts, these principled composers never engaged in narastuti, praising mortals, in exchange for patronage. Their sole, and soul’s, inspiration for composing was the Divine alone. While the Carnatic trinity taught music to students in their homes, they also composed songs spontaneously when glorifying Deities at holy shrines they visited. Having engaged in music as a path to liberation their entire lives, these saints could foresee their death and gracefully accept it, thereafter blissfully merging with the divine feet of their ishta devata.

Annual Aradhanas are celebrated in honor of Carnatic composers. For students of music, this is a time of remembering, learning and performing, as they learn new kirtanas. These compositions are not simply for entertainment or musical accomplishment, but tools for spiritual upliftment. We offer this Insight as an Aradhana reflecting on the stories of eight saints who revolutionized Indian classical music through their profound linguistic, musical and devotional creations.

Glossary of Carnatic terms

kirtana/kriti: Carnatic song

sankirtana: specialized Carnatic songs in Telugu

devaranama: specialized Carnatic songs in Kannada

raga: melodic mode

tala: rhythmic cycle

swara: musical notes

sahitya: lyric in a Carnatic song

gamaka: melodic oscillation

Tyagaraja, Lord Rama’s Songster

“O Raghava, why this curtain between you and me? You are omnipresent; then how can you hide from me!” So sings Saint Tyagaraja in the composition named “Marugelara,” as he awaits the darshan of Lord Rama. His compositions reflect the non-dualistic philosophy of the Advaita sampradaya. This preeminent 19th-century composer-saint, one of the famed Carnatic music trinity, was a genius of swara (notes), laya (rhythm), and sahitya (lyrics). Also known as Tyaga Brahmam or Tyagayya, he is believed to have composed 24,000 kritis, out of which we have access to 800 today. These compositions, mostly in Telugu, cover more than 250 ragas!

His Blessed Childhood

Born in Thiruvarur, near Thanjavur, in Tamil Nadu on May 4, 1767, Tyagaraja was the third son of Ramabrahmam and Sitamma. His ancestors were from Andhra Pradesh (Kakarla village), and hence he composed his songs in Telugu. After his upanayanam, he commenced learning the Vedas, Shastras and Upanishads. He venerated his father and became his ardent student in Telugu and Sanskrit. From his mother he learned the devotional compositions of Purandaradasa and Sri Vijayagopala Yathi Swamigal. One year, on the night before Sri Rama Navami, thirteen-year-old Tyagaraja spontaneously composed his first kriti, the soul-stirring “Namo Namo Raghavaya.” Seeing his son’s great promise, the father sent him to Guru Sonti Venkataramanayya for training in classical music.

Divine Vision of Lord Rama

One day when Tyagaraja was around twenty, his father said he would soon depart this world to attain the feet of Lord Rama. The young man could not bear to hear these words and started to cry; to him, his father was Lord Rama himself. He shared that his one and only goal was for Lord Rama to appear before him in all his beauty and glory. Ramabrahmam, eyes welling up with pride, told his dear son, “You can definitely see Lord Rama if you just chant Rama Nama (the name of Rama) one hundred crore (one billion) times.” Tyagaraja began chanting, “Rama, Rama, Rama, Rama…,” and his father merged with the feet of Lord Rama.

From this point on, Rama Nama was Saint Tyagaraja’s everything—parent, brother, friend, confidant, God and more. Twenty years went by, and he was still immersed in singing the Lord’s name in every waking moment. He married, had a daughter and eventually completed 96 crores of Rama Nama. One day he heard a knock on the door. Opening it, he was overwhelmed by an effulgent blue light in which Lord Rama appeared in front of him! His dream had come true, the mantra had indeed manifested the form of the Lord!

Saint Tyagaraja dedicated his life to singing only for the Lord. Even though four kings from the Maratha dynasty were in rule during Tyagaraja’s time (Tuljaji to Raja Shivaji), he never served any of them. These kings were great connoisseurs of art, language and music. When the composer received a prestigious invitation with many gifts to sing alone in the royal court, he declined with the composition, “Nidhi Chala Sukhama.” “O my mind! Tell me truly, which conduces greatly to happiness—wealth or the sight of the Lord?”

Innovator of Ragas

Saint Tyagaraja created 60 to 70 ragas (in addition to the lyrics and songs in those ragas), usually by making just one change in the swara pattern of an existing raga. Many a time, he wrote only one kirtana in a specific raga. These are known as “ekakriti ragam,” (one-song ragas). His mudra (signature) is his own name and can be found in all his songs. He often presented a statement in the introductory stanza, and then elaborated on the what and why of it in the following verses. The starting phrase of the song also usually defines the raga’s form. Also characteristic are occasional “jumps” in the note structure in many of his compositions. The particular notes (swaras) work closely with the lyrics, and these jumps are often introduced to showcase a certain rasa, or mood.

Tyagaraja’s Bhakti

The divine Sage Narada is said to have given Saint Tyagaraja the musical treatise Swararnava, using which he created many unique ragas. Tyagaraja mentions the text in the song “Swara Raga Sudha,” noting that it had been narrated to Goddess Parvati by Lord Siva. His remarkable compositions were also influenced by the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Srimad Bhagavatam and Bhagavad Gita. The saint pilgrimaged to many sacred sites such as Tirupati, Kanchipuram, Srirangam and Sholingur, composing songs at the temples.

His Legacy Lives On

Saint Tyagaraja had numerous disciples who spread his musical legacy throughout South India. He became so popular in his own time, devotees came to his house daily to listen to him or his students sing. Tyagaraja attained samadhi on January 6, 1847, in Thiruvaiyaru, on the banks of the holy river Kaveri. His message to humankind was simple: to get over the shackles of maya, we need to have total surrender and hold on tightly to the divine feet of Lord Rama. Through his life and immortal songs, the devoted composer demonstrated how music is a means to mukti (liberation).

Learn more

Experience Saint Tyagaraja’s life in the biopic Endaro Mahanubhavulu (2021), a 100-minute film written and directed by Bombay Gnanam. Available with subtitles at: youtu.be/47cDkpuNWG4

Listen to Saint Tyagaraja’s “Bantureethi Koluvu” on Youtube by Uthara Unnikrishnan, complete with lyrics and translation in English: youtu.be/smf7rx-jPMw

Visit the Prasanna Venkatesa Perumal Temple in Madurai, to see the tambura that Saint Tyagaraja used, alongside that of Venkataramana Bhagavathar, the saint’s foremost disciple.

Read The Spiritual Heritage of Tyagaraja (1957) for an in-depth exploration of the saint’s songs and biography

Watch Smt. Vishakha Hari’s Thyagaraja Hrudayam series on YouTube, in Tamil with English subtitles. Our sincere gratitude to her for enlightening us on this genius composer

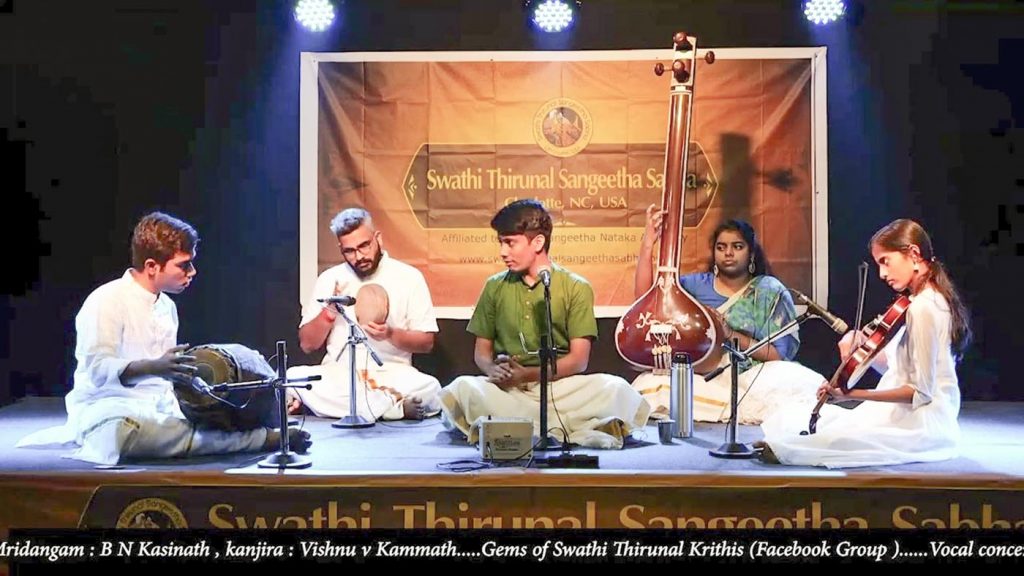

Musicians Celebrate

In 2022, the 175th Aradhana of Saint Tyagaraja was celebrated with added fervor globally. At the heart of these Tyagaraja Aradhana festivals is the musical tribute, during which the composer’s Pancharatna Kritis are sung and played in chorus. These songs, set to Adi talam, are known as the five gems of Carnatic music. His Utsava Sampradaya Kritis accompany temple rituals such as Radha Kalyanam and Sita Kalyanam. Other categories of compositions include Divyanama kirtanas for bhajana settings, as well as two musical dramas, “Prahlada Bhakti Vijayam” and “Nauka Charitram” for Bhagavatas to enact with dance and music, as was commonly the tradition in olden times.

“All his compositions are conversations with Lord Rama, or conversations with his own mind. Both are the same since his mind is completely filled with Lord Rama alone!” —Carnatic vocalist and Harikatha exponent Smt. Vishakha Hari

“Melody is the soul of music and Tyagaraja is the soul of melody.”—Dr. A. Prasanna Kumar, former President of Visakha Music Academy and retired Professor of Politics, Andhra University

A Song by Tyagaraja

Rama Nee Samanamevaru

Ragam: Kharaharapriya; Talam: Roopakam; Language: Telugu

O Lord Rama, who elevated the Raghu dynasty, who can equal you?

Your beloved Sita is tender like the shoot of sweet marjoram.

She is the parrot singing to you in the cage of devotion!

You have brothers who speak such that honey drips from each word.

Hari, Tyagaraja family’s greatest ornament, gentle and soft-spoken Lord!

Shyama Shastri, Singing to the Goddess

In the spiritual mind of Shyama Shastri (1763-1827), he was Goddess Kamakshi’s child, constantly yearning for the Divine Mother’s affection, compassion and protection. This is the tone of his gitams, varnams, swarajatis and kritis. He was a Sri Vidya upasaka, born to Vishwanatha Shastri and Vengalakshmi in Thiruvarur. His compositions were primarily in Telugu, his mother tongue, though he also composed in Sanskrit and Tamil. Shyama Shastri’s father, like his ancestors, was a priest at the Sri Bangaru Kamakshi Amman Temple in Thanjavur. They lived in a house right behind the temple.

In his youth, he spent a lot of time at the temple, where his devotion towards the Goddess grew. In time, he inherited the right to be temple priest. After performing the pujas each day, while still in the shrine, ecstatic compositions would flow from his mind like a gushing river.

Mastery of Music

Young Shyama Shastri was introduced to classical music by his uncle, and later received four months of training from Sangita Swami of Kashi. With the grace of the Goddess, that period of tutelege helped to make him a grandmaster of the art form. He then studied with Pacchimiriyam Adiyappayya, a vina master in the Tanjore royal court.

Shyama Shastri dedicated most of his compositions to Goddess Kamakshi, including three hallmark swarajatis referred to as Ratnatrayam, or Three Jewels. As the architect of the swarajati form, which was originally a dance genre, but now could be sung in concerts, he was an expert in swaraksharas, fusing the swaras (notes) with the sahitya (lyrics). For example, the note “Ga” corresponds with a “Ga” in the lyrics. All his compositions carry the mudra (signature) Shyamakrishna.

The saint composed roughly 300 songs, of which around 75 are available today. He created the Navaratnamalika—nine exquisite songs on Goddess Meenakshi of Madurai—and glorified many other South Indian temple Deities. Shyama Shastri composed several magnificent kritis in ragas like Anandabhairavi and Saveri, and often adopted Mishra Chapu talam for his compositions.

Shyama Shastri was known for his intricate talams, resounding voice, and majestic countenance. When the famed musician Bobbili Kesavayya from Andhra Pradesh challenged the artistry of the Tanjore musicians, Shyama Shastri was sought to represent Tanjore. The composer-saint immediately approached the Divine Mother, singing the kriti “Devi Brova Samayamide” (“Devi! This is the moment to protect me!”). By the grace of Goddess Kamakshi, the saint won with his skilled singing of ragam, tanam, pallavi, mastery of Simhanandana talam and astounding creation of Sharabhanananda rhythm cycle. In a similar musical duel, he defeated Appukutti Nattuvanar, who became an admirer and popularized Shastri’s compositions in Mysore.

He and his wife Lalitha had two sons, Panju Shastri and Subbaraya Shastri. In 1827, he attained the lotus feet of Goddess Kamakshi. Panju Shastri then became the priest of Bangaru Kamakshi. Subbaraya Shastri, a gifted Carnatic composer, had the unique blessing to learn music from each of the Carnatic trinity, starting with his father and later from Tyagaraja and Muthuswami Dikshitar.

Learn more

Enjoy anecdotes from Shyama Shastri’s life and listen to his compositions on the veena with Dr. Jayanthi Kumaresh: youtu.be/JQtffdJGlN0

Listen to Shyama Shastri’s Brovavamma sung in a concert by Carnatic vocal duo Ranjani-Gayatri: youtu.be/jfHhigCtZ2M

A Song by Shyama Shastri

Himadri Sute Pahi Mam

Ragam: Kalyani; Talam: Rupakam; Language: Sanskrit

O Daughter of Snow Mountain! Please protect me.

O Bestower of boons! O Supreme Goddess!

O Sri Kamakshi—abiding in the centre of sacred Meru Mountain!

O Golden Bodied! O Lotus Eyed! O Mind-Born of Sage Matanga! O Mother extolled by Brahma—abiding in lotus, Vishnu, Siva, celestials and great ascetics!

O Mother whose face resembles moon—enemy of lotus!

O Mother whose neck is resplendent with pearl and diamond necklaces! O Creeper of Wish Tree for devotees!

O Gauri—Sister of Vishnu—Shyama Krishna! O Parameshvari!

O Daughter of Mountain! O Mother with dark tresses! O Sri Lalita—Sweet-voiced like a parrot!

Translation by V. Govindan (Shyama Krishna Vaibhavam)

Muthuswami Dikshitar, Blessed by Lord Muruga

“I worship Lord Ganapati of Vatapi, who has the face of an elephant and confers boons on His devotees.” Thus sang Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar in a heartfelt offering to Ganesha. This legendary composer, scholar, vocalist, vina exponent and Sri Vidya Upasaka was the eldest son of Subbammal and Ramaswami Dikshitar, a composer known for his magnum opus Ragatalamalika, featuring 108 ragas set in 108 talas. Muthuswami Dikshitar’s brothers, Chinnaswami and Baluswami Dikshitar, also renowned musicians, performed Muthuswami‘s compositions as a vocal duo. Baluswami pioneered the use of the violin in Carnatic music. Muthuswami Dikshitar lived from 1776 to 1835.

Musicians have identified around 500 compositions by Dikshitar spread over nearly 200 ragas. These include several sets of vibhakti kritis, four ragamalikas, and around forty nottuswarams based on Western melodies loosely resembling raga Shankarabharanam. Vibhakti refers to case-endings in Sanskrit. Dikshitar was known for his brilliant creations in all the different cases. His exposure to British bands playing Irish music at Fort St George in Madras inspired him to fuse that genre with Sanskrit lyrics. He sang with authority about Advaita Vedanta, mantra, tantra and Sri Vidya, often with rhyming lyrics. Like the Nayanmars and Alvars, Dikshitar pilgrimaged to Saivite and Vaishnavite temples—Kanchipuram, Tiruvannamalai, Chidambaram, Tirupati, Srirangam, etc.—glorifying the lands, Deities, festivals, architecture and rituals in majestic compositions.

Chidambaranatha Yogi’s Guidance

Around 1790, Chidambaranatha Yogi—a sannyasin who gave Sri Vidya diksha to his father—took Dikshitar to Varanasi, where he trained him in Sri Vidya upasana, music, Vedanta and yoga. Here the composer encountered the Dhrupad style of Hindustani music. Influences of Dhrupad are evident in the way he handled certain ragas, with characteristic lilts and tilts. Dikshitar also skillfully created Carnatic counterparts to many Hindustani ragas. Upon the passing of Chidambaranatha Yogi, Dikshitar traveled to the temple town of Tiruttani, remembering his guru’s songs in praise of Lord Murugan.

Tiruttani Murugan’s Blessing

When he was chanting the Shadakshari mantra at Tiruttani, an elderly man placed sugar candy in his mouth and asked him to sing. Suddenly the man disappeared and Dikshitar had a vision of Lord Subramanya seated on a peacock, with his consorts, Valli and Devasena, on either side! He realized that the man was none other than the Deity, Lord Subramanya of Tiruttani, and the candy was jnana (knowledge). This explains why the composer adopted the signature Guruguha, a name of Subramanya. After this incident, Dikshitar composed his first song, “Srinathadi Guruguho.” Seven more followed, glorifying Lord Subrahmanya as guru. These make up the Guruguha Vibhakti Kritis.

Dikshitar’s Brilliant Creations

Dikshitar composed mostly in Sanskrit, except for a few songs in Telugu and Manipravalam (a literary language). With his mastery of the vina, using the distinct vainika style, he would explore a raga through expressive gamakas (melodic oscillations), composing meditative creations, usually slow in tempo, on Lord Siva in the form of Tyagaraja, His consort Sri Nilotpalambal and Goddess Kamalambal. His Kamalamba Navavarna Kritis are filled with mystical and musical intricacies, detailing the tantric mode of Devi worship, sacred geometry and the Sri Chakra. He also composed the seven Vara Kritis, one for each day of the week, in seven ragas set to the seven Sooladi talas. His knowledge of Vedic astrology is seen in his Navagraha Kritis. Dikshitar’s disciples include the famed Thanjavur Quartet (Chinniah, Ponniah, Vadivelu and Sivanandam), who formalized the performance repertoire of Bharatanatyam as we know it today.

Learn more

Listen to the blending of Western melodies with Sanskrit lyrics in Muthuswami Dikshitar’s nottuswara composition “Shyamale Meenakshi,” sung by young Sooryanarayanan: youtu.be/5CUword1TPk

Read T.L. Venkatarama Aiyar’s biography of Muthuswami Dikshitar as part of the National Biography Series (1968)

A Song by Muthuswami Dikshitar

Mahaganapatim Manasa Smarami

Ragam: Nattai; Talam: Adi; Language: Sanskrit

I meditate on the Supreme Lord Ganapati, who is worshiped by great sages like Vasishtha, Vamadeva and others.

He is the son of Lord Siva and is praised by Guruguha.

He shines bright like crores of cupids, and is peaceful.

He loves great poetry, drama and other arts.

He has a mouse as a mount, and is fond of sweet modakas.

Annamacharya, Master of Nuance

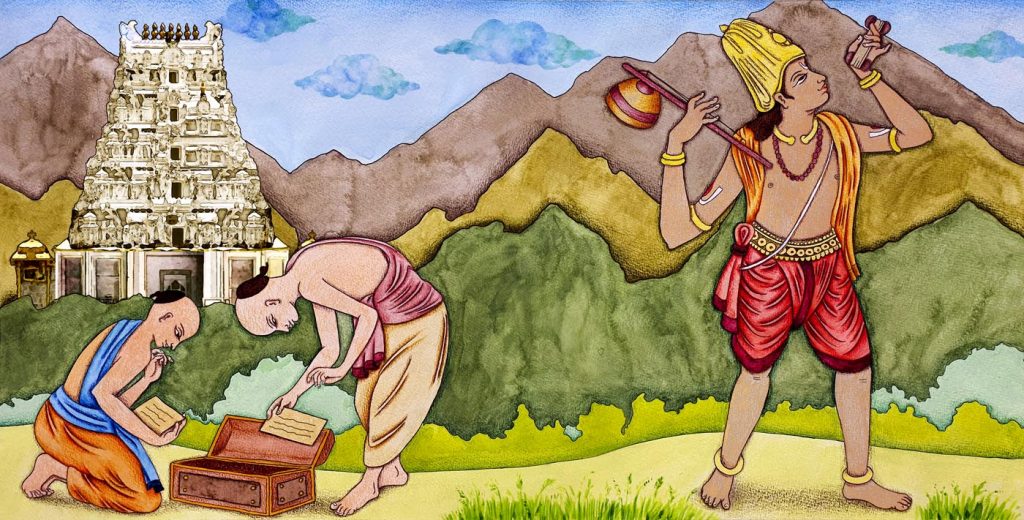

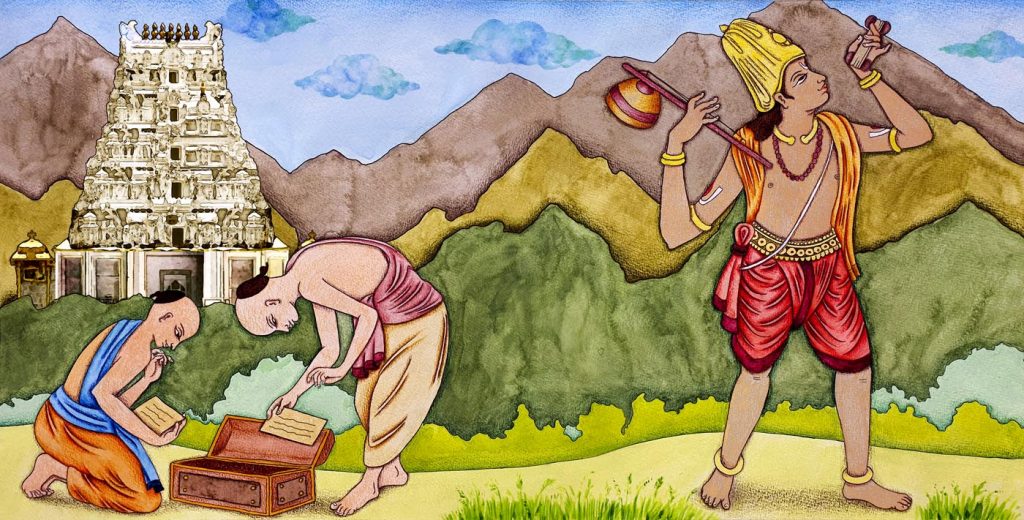

The year 1922 was momentous for the Carnatic music community. A priceless collection of 2,500 copper plates inscribed with 13,000 padams (musical compositions), along with corresponding ragas, were found in a special vault (later named Sankirtana Bhandara) inside a small chamber opposite the hundi (donation box) in the Sri Venkateshwara Temple at Tirupati. These devotional offerings were composed by the illustrious 15th-century composer-saint Annamacharya.

Annamacharya Charitramu, a poetic biography composed in dvipada (rhyming couplets) by Tallapaka Chinnanna, grandson of Annamacharya, describes the life and contributions of the saint. A Nandavarika Brahmin couple, Narayana Suri and Lakkamba, were struck by a dazzling light from the sword of Lord Venkateshwara while they were prostrating in front of the flagpole, dhvajastambha, on a visit to the Tirumala Temple. Soon thereafter, on Vaishakha Purnima in the year 1408, in Tallapaka village in Andhra Pradesh, the family welcomed a baby boy, Annamayya. The baby was devoted to the Lord from birth; he cried incessantly, stopping to no lullaby unless it was the sweet sound of Vishnu’s name.

Annamayya started composing poetry at the age of sixteen, inspired by a vision of Goddess Alamelumanga and Lord Venkateshwara while on pilgrimage to Tirupati. A sage in the Tirumala temple initiated the boy into the Srivaishnava tradition, then sent him home, where he married Timmakka and Akkalamma. He then became a disciple of Shathakopamuni, from whom he learned Vedanta.

Rejecting Narastuti

Saluva Narasimha Raya, ruler of Tanguturu, invited the composer to his court. Impressed by the saint’s remarkable songs, the king asked for a song in praise of himself. Annamayya was shocked at his request and refused to engage in “narastuti” (praise of human being). He told the king he would compose songs only for the Lord. His ego hurt, the king threw the saint in prison. Legend says that when Annamacharya sang to the Lord with utmost devotion, his shackles miraculously broke free. The king realized his folly and released the saint. Annamacharya returned to his spiritual home, Tirumala, the court of the Lord. In the words of scholars Velcheru Narayana Rao and David Shulman, “Annamayya was Venkateshvara’s court poet, and theGod rewarded him and his family lavishly in the royal manner.”

Traditional accounts say Annamacharya considered Purandaradasa, a younger Kannada saint-composer, to be an incarnation of Vitthala. Purandaradasa paid his respects to Annamacharya by singing about him as the incarnation of Lord Venkateshwara.

Sankirtanas for Every Occasion

Composing a song each day as a form of worship, Annamacharya sang an astounding 32,000 songs, celebrating the Lord’s daily rituals and temple festivities, from morning prayer to nighttime lullaby. Annamayya’s songs are very popular in the Carnatic community. The lullaby “Jo Achyutananda” musically depicts Sri Krishna Leela; “Sriman Narayana” and “Adivo Alladivo” glorify the God of Tirumala. Annamacharya’s songs express nuanced messages of bhakti and philosophy from Hindu scriptures such as the Puranas and Vedas in beautiful Telugu poetry. Full of vivid imagery and subtle emotions, his work is a treasure trove to classical dancers who creatively enact stories of divine love and oneness in their choreography.

In addition to 32,000 sankirtanas in accessible Telugu, Annamacharya composed several shatakas (sets of a hundred verses), including the “Venkateshwara Shataka,” the “Ramayana” in dvipada meter in Telugu, “Sringara Manjari” in Telugu, “Venkatadri Mahatmya” in Sanskrit, and prabandhas in various languages. His heart and mind became so pure that his words carried immense power.

Sringara and Adhyatma Songs

Annamacharya’s devotional songs are in two complementary genres, as indicated on the ancient copper plates. The majority of the songs we have today are sringara sankirtanas, which poetically depict the affection between Lord Venkateshwara and his beloved wife Alamelumanga. Usually in the female voice, these songs brim with Madhura Bhakti, in which the devotee becomes the heroine (nayika) and God is the hero in a divine play of love and longing between the individual self and the cosmic self. The adhyatma sankirtanas, usually sung in the poet’s own voice, are more introspective and metaphysical, addressing moral and spiritual values such as detachment. While the saint glorifies and expresses affection and surrender to the Lord in some songs, in others he argues and taunts the Lord, or confesses fears and self-doubt.

Annamacharya wrote his sankirtanas on palm leaves. Late in his life or soon after his samadhi, given his popularity in his own times, his son Peda Tirumalacharya converted them to copper inscriptions, a costly endeavor that preserved the songs for generations to come. These copper plates have been found not only in Tirupati but also in several other South Indian temples, including Srirangam, Ahobilam and Chidambaram. Vocalist Dr. M. Balamuralikrishna, an expert on Annamacharya sankirtanas, set music to over 800 of these compositions, as the original tunes are unknown. In 1979, Smt. M.S. Subbulakshmi’s soulful renditions of Annamacharya’s songs further spread them nationally and globally. The prolific composer’s saintly life ended in 1503. His songs live on in temples and concert halls, enrapturing listeners in the Lord’s presence.

Learn more

Read God on the Hill: Temple Poems from Tirupati by Velcheru Narayana Rao and David Shulman, an incredible resource on Annamacharya with English translations of 150 poems from copper plates

Listen to “Jo Achyuthananda,” a soothing lullaby by Annamacharya, sung melodiously by Sooryagayathri (with lyrics and translation in English): youtu.be/xcSBPkUxOJE

Visit the 108-foot-tall sculpture of Annamacharya at Tallapaka, birthplace of the saint

A Song by Annamacharya

Muddugare Yashoda

Ragam: Kurinji, Talam: Adi, Language: Telugu

He is the lovely pearl of Yasoda, playing in her front yard.

He is the all-powerful and perfect son of Devaki.

He is the ruby of all gopikas. He is a diamond-like weapon for the adamant Kamsa. He is the emerald of the three lokas, radiating light.

He is little Krishna staying with us.

He is the coral of beautiful Rukmini. He is the agate that lifted Govardhana mountain. He is the cat’s eye in conch and discus.

He is the lotus-eyed. He is our savior.

He is the topaz on the heads of Kaliya (serpent). He is sapphire. He is the divine gem in the ocean of milk. He is Padmanabha moving like a boy amongst us.

Translation: Damodara Rao Dasu

“I am constantly amazed by the wealth of life truths and wisdom in his compositions and the profound philosophy therein. I also like his sweet language and dialect while describing God.” —Venkat Garikapati, author, speaker, Annamayya scholar & banker

“Annamayya was such a genius that his writing encapsulated complex ideas in descriptive phrases, often employing the vernacular to connect with the common man. This adroit use of language and ideas offers immense choreographic possibilities to the dancer.” —Dr. Anupama Kylash, Annamacharya scholar and senior practitioner of Kuchipudi and Vilasini Natyam

Purandaradasa, Father of Carnatic Music

“I have offered 479,000 kritis to you, O Vasudeva, all because of your grace.” Thus sang Purandaradasa in “Vasudevana Namavaliya.” This genius composer was born in Karnataka in 1484, three centuries before Saints Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar and Shyama Shastri. In fact, the first compositions Saint Tyagaraja learned were the Devaranamas of Purandaradasa, whose greatness he sings about in “Prahalad Bhakti Vijayam.” Purandaradasa is revered as Sangita Pitamaha, grandfather and founder of Carnatic music pedagogy. He systematized the early lessons in Carnatic music that students learn even today. He wove the essence of the Vedas into accessible songs in Kannada and musical Sanskrit. His creations were popularized by modern-day Carnatic legends Madras Lalithangi, her daughter M.L. Vasantakumari, and T.K. Govinda Rao.

The Haridasa of Karnataka

Purandaradasa sang his heart out to the Lord mainly in the form of Vishnu and Krishna. He composed one of the earliest Carnatic lullabies, “Thoogire Rangana,” from which composers drew inspiration in later centuries. He dedicated kritis to Lord Ganesha, Lord Siva, Narasimha, Goddess Mahalakshmi, Tulasi, Lord Rama and Lord Hanuman.

The Haridasas, “servants of Sri Hari,” shaped Kannada Vaishnava devotional literature through their Dasa Sahitya, singing the dvaita philosophy of Madhvacharya. As with their spiritual cousins—the Kannada Virashaiva saints and Tamil Alvars—the Haridasas’ relationship with God is intuitive and experiential. They sang about God’s availability to one and all. Other famed Haridasa composers include Kanakadasa, a follower of dvaita philosopher Vyasatirtha from the Madhva order of Udupi, who initiated Purandaradasa (ca. 1525). The pen-name Purandara Vitthala features in all his compositions.

Affluent Childhood

Varadappa Nayaka and his wife Kamalabai were affluent diamond merchants. Childless for many years, they prayed to Lord Srinivasa, promising to name the child after him if they were blessed with progeny. In 1484, a beautiful baby boy was born. They named him Srinivasa and fondly called him Chinnappa Nayaka (the future Purandaradasa). Chinnappa was married early to Lakshmibai, and they had several children together. His parents passed away soon after that, leaving the diamond business for Chinnappa to look after. He was very proficient in moneymaking, and also miserly; he spent all his time and energy increasing the business. Eventually he made nine crore (nava koti) rupees and was thenceforth referred to as Navakoti Narayana. Lakshmibai, on the other hand, was a generous woman who only wanted to do danam, give to the needy.

Spiritual Transformation

One Friday morning, an elderly bhagavatar singing the name of the Lord approached Chinnappa’s shop. Eagerly waiting for the man to produce an expensive gem that he wanted to pledge in exchange for money, Chinnappa Nayaka was disappointed to see only turmeric-smeared yellow rice, an indication that the man was seeking charity. The elder explained that his daughter was getting married, and their family needed financial assistance. Chinnappa rudely declined and had his bodyguard escort the beggar out.

Meanwhile, Lakshmibai was engaged in Lakshmi Puja at home, praying to the Goddess to bless her with the opportunity to do danam. That very moment she heard a knock on the door and someone calling out to her, “Amma!” The elderly gentleman had arrived at her house. He blessed her with all auspiciousness and prosperity, as was customary, and then asked for her kind help.

She immediately removed her diamond nose stud and gave it to him. The bhagavatar went back to Chinnappa Nayaka’s shop and presented the nose stud for trade. Chinnappa was shocked to see his wife’s jewelry! The bhagavatar joyfully shared that he came across a huge mansion nearby, where the lady of the house was extremely generous. Chinnappa rushed back to his house and asked Lakshmibai to show him her nose stud. Lakshmibai knew her husband would be angry and immediately worshiped the Tulasi, which represents the Divine Goddess in the Madhva sampradaya. She was in distress as she did not want to lie to her husband. Suddenly she felt something in her hand—lo and behold, it was her diamond stud, the very same one she had given away! She rushed to give it to Chinnappa Nayaka, who was equally astounded. As he scrutinized the nose stud, it radiated a divine effulgence in which he had a vision of Lord Ranganatha reclining on Adi Shesha.

Purandaradasa gave away all his wealth and began his spiritual journey. He composed innumerable songs on Sri Krishna as Vitthala, of which musicians have access to around 1,000 today. His famous compositions include “Bhagyada Lakshmi Baramma,” where the saint welcomes Lakshmi, the Goddess of abundance, and the soulful “Venkatachala Nilayam” for the Lord of Tirumala Hills, Tirupati Venkateshwara. Themes in his songs include social reform and bhakti-filled poetry about the adventures of Lord Krishna. Hindustani classical musicians such as Bhimsen Joshi have adopted Purandaradasa kritis into their repertoire.

During Purandaradasa’s time, the center of devotional activity was Hampi, the magnificent capital of the Vijayanagara empire. Legends say Purandaradasa settled there with his wife and children. With bells on his ankles, tulasi mala on his neck, tambura in hand and the Lord’s names on his lips, he sang his kirtanas through the streets of Hampi. Saint Purandaradasa lived for about 80 years, until 1564, taking sannyasa towards the end of his life.

Learn more

Watch & listen as legendary vocalist M.S. Subbulakshmi performs the song “Jagadoddharana” at the UN Concert in 1966: youtu.be/ArOsyp6dSLE

Listen to Tamburi Meetidava, a soul-stirring composition by Saint Purandaradasa, rendered by Raghuram Manikandan: youtu.be/uCCaFqRoihQ (with lyrics and translation in English)

Watch the documentary film Kanaka-Purandara (English, 1988) by director and playwright Girish Karnad, available in full here: youtu.be/aGdb19OECiY

Visit the Purandaradasa Mantapa in Hampi, Karnataka, India

A Song by Purandaradasa

Jagadoddharana Adisidaleshoda

Ragam: Kapi, Talam: Adi, Language: Kannada

Thinking that the Savior of the world was her son, Yashoda played with embodiment of all great qualities.

The one whose greatness is infinite and beyond measure, and the gem amongst children, Yashoda played with Him.

The one who is smaller than the atom and bigger than infinity, and who is enigmatic, Yashoda played with Him.

The one who is Supreme among men, God of all worlds, whom Purandara adores, Yashoda played with Him.

“If we analyze Purandaradasa’s songs, we will find so many different subject matters. Bhakti, yoga (meditation), sringara (love), jnanamargam (attaining spirituality), philosophies pertaining to leading a good life, Vedanta, as well as aspects of music and music grammar.” —Dr. M L Vasanthakumari, Padma Bhushan awardee and Sangita Kalanidhi

“Purandaradasa has been justly termed the father of Karnatak music. He was not merely a composer but a lakshanakara of the highest calibre. The system of South Indian music, as we now know it, is entirely his gift.” —T.V. Subha Rao, lawyer turned musicologist, founding member of The Music Academy, Madras

Sadasiva Brahmendra, Ascetic Lyricist

“Everything is pervaded by Brahman, O dear!” Thus sang Carnatic composer Sadasiva Brahmendra, an extraordinary philosopher, recluse and enlightened being. He was born to Meenakshi Sundareshwar and Parvati Ammal near Pudukkottai, Tamil Nadu. As he was conceived after a pilgrimage to Rameshwaram, he was named Sivaramakrishnan. A brilliant child, he studied the Vedas, music, Sanskrit and more in Tiruvisainallur, a prominent center of education and Hindu culture. In time, as an established Advaita scholar, he was so immersed within that he would spontaneously compose songs. Around eighteen, his parents asked him to return to Madurai for marriage. As the engagement ceremony neared, he realized that his purpose in life was to realize God, which he could not focus on with a family to care for. He left home in search of the ultimate Truth.

Meeting His Guru

Arriving in Kanchipuram, the youth met Sri Paramasivendra Saraswati Swami, the 57th pontiff of Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham. At that moment, seeing the radiance of knowledge in Sivaramakrishnan’s face, Swamiji took him as a disciple and gave him sannyasa diksha, naming him Sadasiva Brahmendra Saraswati. One of the true mystics of Bharat, Sadasiva Brahmendra belongs to the same Advaita lineage as Adi Shankaracharya. He is often referred to as a jivanmukta (liberated soul), Brahmajnani (knower of Brahman) and avadhuta (a mystic or sage who has utterly shaken off worldly attachments).

Musical Contributions

Sadasiva Brahmendra (ca. 1700-1756) wrote many Carnatic compositions in Sanskrit, masterfully blending bhakti with Advaita philosophy. His ecstatic songs, underscoring the importance of nama smarana (remembering God’s name), carry a simple elegance with layers of philosophical truth showcasing his mystical experiences. Only around 25 of his songs are in circulation today, but these highly regarded pieces are frequently heard in concerts. Popular compositions include “Manasa Sancharare,” “Bhajare Gopalam,” “Jaya Tunga Tarange Gange” and “Bruhi Mukundeti.” He used the word Paramahamsa or simply Hamsa as signature. He authored several treatises, including Brahmasutra Vrtti (commentary on the Brahma Sutras), Yoga Sudhakara (commentary on Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras) and Siddhanta-kalpa-valli.

Lifelong Vow of Silence

Sadasiva Brahmendra loved to debate. One day while his guru was immersed in Siva puja, there was incessant chatter outside, fueled by Sadasiva Brahmendra and other students who were debating some topic. Paramasivendra Saraswati grew annoyed. Coming outside, he asked, “Sadasiva, won’t you ever stop speaking?”—and that was the last time that Sadasiva Brahmendra spoke. Taking his guru’s words as an ultimatum, he plunged into silence (mouna) and remained in that intense state of spiritual penance and solitude. When he met other saints, such as Sridhara Ayyavaal and Sri Bodendra Saraswati, they would sit under a mango tree to discuss philosophy. Sadasiva Brahmendra would write his thoughts on the ground, while the other two saints would speak to share their views.

Over time, external silence and persistent meditation led to deep inner bliss. Eventually, the stillness of samadhi took over so much so that certain societal norms no longer seemed important. The ascetic wandered in the forests or near the Kaveri River in a trance-like state of divine contemplation, wearing only a loin cloth, sometimes less. He shed everything of the materialistic world, speech, propriety, bodily comforts, even clothes. Onlookers labeled him a madman. When Paramasivendra Saraswati heard of his student’s state, he exclaimed with tears of joy, “Will I ever be so fortunate!” He realized that his disciple had become a true avadhuta, unbound even by sannyasi dharma.

Despite his aloofness from the world, he installed shrines at various temples, including the Ganapati shrine at the Tirunageswaram Naganathar Temple, and a Hanuman murti in the Prasanna Venkateshwara Temple in Thanjavur.

Sringeri Jagadgurus

The Jagadgurus of the Sringeri Sharada Peetham had deep reverence for Sadasiva Brahmendra and his Atma Vidya Vilasam, even incorporating it into their practice. This text on renunciation, considered the author’s spiritual autobiography, describes the characteristics of a knower of Brahman, his state of mind and behavior. Sri Sacchidananda Shivabhinava Nrisimha Bharati was an ardent devotee of Sadasiva Brahmendra. He visited his samadhi at Nerur, where he famously meditated and fasted for three days and had a divine vision of the saint. He then composed two Sanskrit works glorifying the saint’s life and philosophical contributions: Sadasivendra Sthavam and Sadasivendra Pancharatna Stotram. Much of what we know about this composer-saint today comes from the former text.

Divine Miracles

In his Autobiography of a Yogi, Swami Yogananda writes, “Immersed one day in samadhi on the bank of the Kaveri River, Sadasiva was seen to be carried away by a sudden flood. Weeks later he was found buried deep beneath a mound of earth. As the villagers’ shovels struck his body, the saint rose and walked briskly away.” In another story Sadasiva Brahmendra’s arm was cut off by an angry attacker, but he simply reattached it and continued with his day. There are also stories of his compassion for humanity expressed through miraculous deeds. These incidents were testaments to Sadasiva Brahmendra’s state of samadhi, during which his mind was so completely absorbed in supreme consciousness that his body followed suit and transcended itself. The silent sage Sri Sadasiva Brahmendra attained Mahasamadhi in 1756.

Learn More

Listen to Sadasiva Brahmendra’s soul-stirring Pibare Rama Rasam by Rahul Vellal, with lyrics and translation: youtu.be/vJxVWF8KjFI

Pilgrimage to Sadasiva Brahmendra’s shrine in Nerur, installed by the Raja of Pudukkottai

A Song by Sri Sadasiva Brahmendra

Sarvam Brahmamayam

Ragam: Madhuvanti, Talam: Adi, Language: Sanskrit

Everything is pervaded by Brahman!

Everything is pervaded by Brahman, O dear!

What ought to be spoken; What ought not to be spoken,

What ought to be created; What ought not to be created!

What ought to be learnt; What ought not to be learnt,

What ought to be revered; What ought not to be revered!

What ought to be understood; What ought not to be understood!

What ought to be enjoyed; What ought not to be enjoyed!

At all places, at all times, ‘Hamsa’ meditation-

The cause for liberation, ought to be practised, O dear!

Translation: Sharanya Bharathwaj

“Brahmendra’s kirtanas shine like a crest jewel in a Carnatic concert, without which the concert would be bare.”

—Sri Sri Krishna Premi Swamigal

“It is the life of this sage that made a very deep impression in my mind. I came to a very definite conclusion that there is a sublime divine life independent of objects and the play of the mind and the sense. The sage was quite unconscious of the world. He did not feel a bit when his arm was cut off. He ought to have been absorbed in the Divine Consciousness, he ought to have been one with the Divine.” —Sri Swami Sivananda, Divine Life Society

Oothukkadu Venkata Kavi, Rhythmic Virtuoso

“Taamita Tajjam Taka Tajjam Takadika Tajjam Taam,” sings Oothukkadu Venkata Kavi rhythmically in his Kalinga Narthana Thillana, as he sees young Krishna dancing in his mind’s eye on the swaying serpent Kalinga. The composer’s genius can be seen in the way a particular word in the song resembles the hissing of the serpent. Replete with the dancing of intricate jatis (rhythmic syllables) and flowing lyrics, this song is a dramatic introduction to this great Carnatic composer.

Oothukkadu: Where Krishna Danced on a Serpent

More formally known as Oothukkadu Venkata Subbaiyer, this composer dedicated his life (ca. 1700-1765) to “Kaliya Narthana Krishna”—the name of the presiding Deity in Oothukkadu town, which is featured like a secondary signature in his many compositions. He was born Venkata Subramaniam, the eldest of five children, to Tamil Smarta parents Subbu Kutti Iyer and Venkamma in Mannargudi near Thanjavur. Later they moved to the village of Oothukkadu.

Venkata Kavi’s family Deity was Goddess Kamakshi, but his mind and heart were enraptured by Kalinga Narthana Krishna. The great poet composed on a staggering range of topics. He composed operas on the Mahabharata, Ramayana and Srimad Bhagavatam. Around 200 of his songs in his Bhagavatam opera musically bring to life scenes from the tenth canto of the Purana, colorfully depicting Sri Krishna Leelas. He also composed songs on Vinayaka, Saraswati, Siva, Karttikeya, Devi (including the famous Kamakshi Navavarana kritis), Rama and Anjaneya. In addition, he composed songs on great saints such as Shuka Brahmarishi, Valmiki, Vyasa, Kannappa Nayanar, Jayadeva, Andal and Bhadrachala Ramadasu. His compositions show that he was inspired by the devotion of the 12 Alvars, 63 Nayanmars and composer-saints such as Purandaradasa and Tulsidas.

During the Maratha rule in the Tanjore region between the 17th and 19th centuries, the Bhagavata mela tradition flourished in South India, especially in villages like Oothukkadu. Our virtuosic composer Venkata Kavi was influenced by this tradition, which might explain his many operas and works that were suited for music, dance and theater, as well as the handful of songs in Marathi. Venkata Kavi was never keen on publicizing his music, and would sing his songs in isolation, mostly at night, once refusing to sing at the king’s court upon invitation. Venkata Kavi was married to his devotional music, and remained a celibate for life.

Lord Krishna as Guru

As a youth, he wanted to learn formally from a great musician called Shri Krishna Yogi. However, Krishna Yogi did not accept him as a disciple, for reasons unknown. The disappointed Venkata Kavi went to his mother, who advised him to surrender to Lord Krishna in the Kalinga Narthana temple. It is believed that the Lord appeared before Venkata Kavi and blessed him with musical knowledge. Thereafter, Venkata Kavi started composing and referred to Lord Krishna as his guru in many songs.

We have around 600 of his compositions today, which were originally scribed in palm leaf manuscripts by his family. His dazzling creations are known for their unpretentious devotion, humility and state of blissful exuberance. Like other saintly composers in his time, Venkata Kavi traveled to temple towns such as Srirangam, Kanchipuram, Madurai, Udupi, Pandharpur, Chennai, Sikkil, Palani and Tiruvarur. We know this through the songs he dedicated to the presiding Deities of these holy lands.

Master of Language, Rhythm & Melody

When conversing with the Lord, he sang in Sanskrit. When he sang about (and as) the folk of Vrindavan, he used colloquial Tamil. To communicate deep philosophical truths, he wrote in scholarly Tamil. Venkata Kavi’s creations are incredibly rhythmic and so full of rhyme that if one were to simply read the lyrics, the appropriate tala would fall into place!

His songs melt our hearts with devotion for the mischievous young Lord Krishna. These compositions were not popular in his own time, largely due to the fact that he did not take on disciples who would propagate them. His works were brought to the mainstream in the 1940s by legendary Harikatha exponent Needamangalam Krishnamurthy Bhagavatar, one of Venkata Kavi’s brother’s descendants.

Tamil Treasures on Lord Krishna

Venkata Kavi composed several musical operas as well as ragamalikas in Tamil. His hugely popular Tamil songs include the mellifluous “Alai Payude” and “Pal Vadiyum Mugam.” His song “Maadu Meikum Kanne” is an enchanting dialogue between little Krishna and his mother Yashoda, in which she tells him not to go outside, and he gives her a long list of reasons as to why he should do just that!

“Thaye Yashoda,” another masterpiece, was secretly noted down and learned by Rudra Pashupati, a nadaswaram player of Tanjore court who admired Venkata Kavi’s soul-stirring renderings. In this song, the Gopis of Vrindavan complain to Yashoda about the incessant pranks of her mischievous son Gopalakrishnan. One of the verses of the song presents the complaint of an exasperated Gopi thus: The other day, we welcomed two guests to our home. After eating, they fell soundly asleep on the verandah. Kannan saw them sleeping. He had just finished eating butter and had some on his hands. He smeared the butter on their mouths and disappeared. When we discovered the butter was missing, we went in search of the thief. The guests were caught! Kannan had eaten the butter, but our guests, with butter on their mouths, were blamed. What mischief! What songwriting!

Learn more

Download “Oottukkadu Venkata Kavi” app on Google Play or the App Store to immerse yourself in the composer’s songs and enjoy the excellent website: venkatakavi.org

Listen to the hugely popular Maadu Meikum Kanne by vocalist Smt. Aruna Sairam: youtu.be/iDKEbj-PDYk

Watch rhythmic and energetic music/dance performances of Kalinga Narthana Thillana on YouTube, such as: youtube.com/watch?v=sU1SNjnGcP0

A Song by Venkata Kavi

Parvai Ondre Podume

Ragam: Surutti, Talam: Adi, Language: Tamil

Just one mischievous glance from Krishna’s eyes is more than enough for me.

So what if these two celestial treasures of the conch and the lotus were forcefully given to me; I would still treasure a single glance from Krishna’s eyes more.

With a face (and dark curls) like a dense black cloud and eyes so luminous that they make one wonder if they are the sun and moon,

Will you not open those oceans that are your dark eyes just a bit and shower a deluge of your compassion so that it warms the depths of my soul?

Should I describe the time when little Krishna went beside his mother Yashoda and stole butter from right under her nose?

Or should I describe when Krishna, having stolen the butter, embraced his mother from behind, and pleaded with his eyes with me to not tell her about it?

“Ootthukkadu Venkata Kavi is in the same stature as the famed Trinity of Carnatic Music” —Carnatic vocalist Padma Vibhushan Dr. Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer

“The evidence available proves that he was one of the most prolific, imaginative, original and versatile composers in Indian culture. His style—with dazzling contrasting passages, complex talas, scholarly lyrics but evocative melody—definitely forms one of five distinct composing styles in Carnatic. —Chitravina N Ravikiran, Chitravina exponent, vocalist, music educator and scholar

Maharaja Swati Tirunal, King and Composer

The maharajas of India were highly cultured and deeply religious, considering themselves as dasas, or servants, of the Lord. The royal family of Travancore governed their kingdom as representatives of Lord Padmanabha (Vishnu).

Swati Tirunal was born in the sovereign state of Travancore, now a part of Kerala, in 1813 to Raja Raja Varma Koyi Tampuran and Maharani Lakshmi Bai. The well-known Malayalam lullaby, “Omana Thingal Kidavo,” was composed by the eminent court poet Irayimman Thampi on the birth of this royal baby. Swati Tirunal’s mother passed away when he was merely two, and he was brought up by his father and his maternal aunt, Sri Parvati Bai.

The Erudite Prince

Groomed to be a king, Swati Tirunal excelled in mathematics, music and literature. By age seven, he had mastered Malayalam (his mother tongue) and Sanskrit, and was being tutored in English, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Marathi and Urdu. The brilliant child was constantly in the company of court musicians, poets and scholars. He quickly learned the fundamentals of Carnatic music and deepened his insights with celebrated musicians who performed in the Travancore court. Soon Swati Tirunal was ready to express his devotion to Lord Padmanabha through music, and thus began his journey in composing.

At age sixteen, Swati Tirunal was crowned king and ruled for eighteen years. He was a progressive leader, admired by his people and open to new initiatives that modernized Travancore into a model state. During his visionary governance, he brought about many social and legal reforms. He also initiated the Trivandrum Public Library (now called State Central Library), a government printing press, English-medium schools offering free education to boys and girls, ayurvedic and allopathic hospitals, an astronomical observatory, a meteorological observatory, a museum and even a zoo.

King, Devotee & Composer

Maharaja Swati Tirunal used over 100 ragas in around 500 compositions available to us. His deeply devotional compositions were mostly about Lord Padmanabha and Maha Vishnu. In addition, a good number were dedicated to Krishna and Rama. He also glorified Ganapati, Siva, Devi, Karttikeya and Hanuman, as well as composed on Advaita philosophy. He authored several literary works, including Bhakti Manjari (a philosophical poem of over 1,000 shlokas), Padmanabha Shatakam and two musical plays, Ajamila and Kuchela Upakhyanas.

Swati Tirunal composed effortlessly in Sanskrit; sometimes making it easily accessible and at other times adorning the song with complex linguistic patterns. While the majority of his compositions are in Sanskrit, several are in Malayalam and Manipravalam (an amalgam of Sanskrit and Malayalam), Telugu, Kannada and Hindi. Swati Tirunal was unique for having composed in so many genres and in so many languages. He employed several forms in his compositions: varnam, swarajathi, kirtanam (most of his songs are in this style), padam, thillana, javali, ragamalika, ragamalika shlokam and compositions suitable for Harikatha (musical discourses).

Dance and Hindustani Music

Swati Tirunal was brilliant at composing for classical dance, and his padams are used extensively in Mohiniyattam and Bharatanatyam. Exploring the Vaishnava motif of the devotee seeking the compassion of the Lord, these esoteric songs are full of colorful and vivid imagery describing the intimate relationship between God and human. He composed nine songs in nine ragas in praise of the Goddess to be sung on each of the nine nights of the Navaratri festival. Swati Tirunal’s Navaratna Malika, another unique set of songs, explores nine forms of bhakti.

While other famed composers like Muthuswami Dikshitar adapted Hindustani ragas to suit the Carnatic framework, Swati Tirunal used them in their original form without modifications. He composed in several Hindustani forms with ease, including khayal and dhrupad, as well as in the Marathi abhang style. His devotion to Lord Padmanabha was so all-encompassing that instead of his own name, the monarch always signed his songs with the divine name Padmanabha or its variations, such as Jalajanabha, Pankajanabha and Sarasijanabha.

Patron of the Arts

As a connoisseur and promotor of the arts, Tirunal provided patronage to many leading classical dancers, musicians and visual artists. Vadivelu, one of the members of the famed Tanjore Quartet and a disciple of Sri Muthuswami Dikshitar, was one of Swati Tirunal’s favorites. Vadivelu was an acclaimed violinist, vocalist, composer and dance exponent.

In the last years of his life, Maharaja Swati Tirunal witnessed the death of several of his family members and spent most of his time in solitude, engaging in the worship of Lord Padmanabha. He let go of his mortal form in 1846 at the young age of 33. In the words of Dr. Achuth Sankar S. Nair, “the Swati star appeared, shining brightly but briefly.”

Learn more

Listen to Swati Tirunal’s Bhogindra Shayinam, beautifully rendered by Raghuram Manikandan & Sooryagayathri: youtu.be/QeAYXZMxYbU

Enjoy Swathi Tirunal’s Hindustani khayal-style Aaye Giridhar Dware by Kruthi Bhat: youtu.be/leA1ULUDPEw

Read more than 70 articles on the life, times and music of Swathi Tirunal: www.swathithirunal.in/articles.htm

Browse the lyrics and translations of Swati Tirunal’s multilingual compositions at: swathithirunalfestival.org/swathi-thirunal/compositions

Music Festivals

Swathi Sangeetha Utsavam, or Kuthiramalika Festival, is a ten-day music festival commemorating the legacy and mammoth contributions of Maharaja Swathi Tirunal. It takes place every January in the courtyard of the Kuthiramalika palace built by Swathi Tirunal on the southeastern side of Padmanabhaswamy Temple in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. The festival brings together top performing artists from the Carnatic and Hindustani traditions who sing the Maharaja’s compositions.

“Aliveni,” a Song by Swati Tirunal

Ragam: Kurinji; Talam: Chaapu; Language: Malayalam

O Aliveni-tresses having the hue of a black bee! Alas! What shall I do now? O Manini, the respectable lady!

Lotus-eyed Sri Padmanabha has not come yet! What shall I do?

O Komalangi, having a charming form! Tell me, what is the use of all these: the humming of the bees, the gentle breeze, sandal paste and fragrant flowers, like jasmine, etc., if my beloved does not turn up?

I do not know who is the blessed damsel on this earth, enjoying the company of Sarasaksha, the one who resembles Cupid! I keep looking out for Him to come by the usual path. I cannot see, as my eyes are brimming with tears.

Has my darling forgotten all the sweet words He uttered when we were together? O Kambukanthi, one with a neck like a conch, don’t delay anymore. Please tell Him my miserable state and bring Him at once to me.

Translation: Sangita Kalanidhi T.K. Govinda Rao

“Maharaja Swati Tirunal of Travancore was a multi-faceted personality, who pursued South Indian classical music, North Indian classical music, dance, poetry, science, astronomy and languages with equal ease.” — Vidwan Prince Rama Varma, Carnatic vocalist and vina exponent

“Swati Tirunal Maharaja’s compositions are immortal because we see Padmanabha in them, we hear and feel Padmanabha in them.” —Mysore Vasudevacharyar, Carnatic musician and composer

About the author & the artist

Lakshmi Chandrashekar Subramanian is an LA-based vocalist who brings devotional singing, scholarship and storytelling onto one platform. With an M.A. in religion from Stanford, she writes on India’s poet-saints and has recorded several albums with her mother and guru, Padmini Chandrashekar, in her hometown of Singapore. Lakshmi performs concerts of Electronic Bhakti Music with her husband Aks. www.eclipse-nirvana.com

Baani Sekhon earned her masters in fine arts from College of Arts, Chandigarh, India. After substantial experience in the creative industry, Baani opted to work as a freelancer and art consultant from home. Commissioned illustrations keep her amply engaged. She writes about art, enjoys research projects and maintains a blog. myartpoint.com