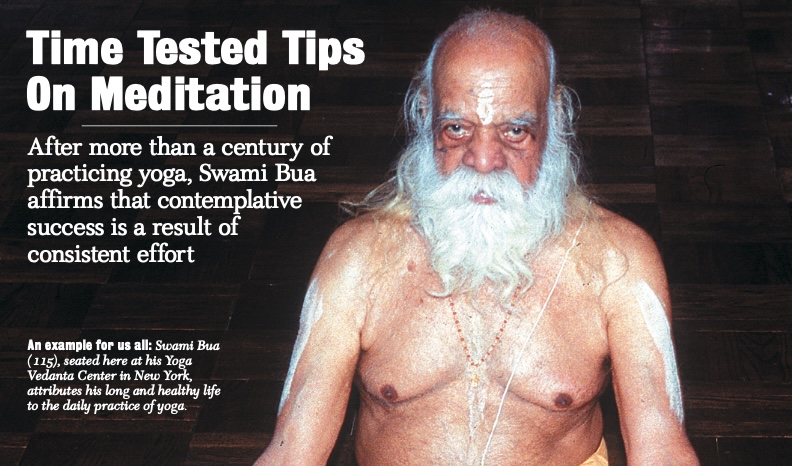

By Swami Bua

Even happy people often look for change in the ordinary routines of their lives. Although they are dutifully consumed in the daily challenges of earning a living, they admittedly fall prey to moments of introspectionÑeven during the busiest of schedulesÑwhen they feel that deep, soulful urge to try something new. A few come to know of great powers lying latent within and fancy they might cultivate some of that potential themselves.

Typical advice for invoking these inherent powers stresses the need for sitting in still concentration and living in a calm state of mind while not dwelling on past or future. One practice commonly advised to achieve this rare tranquility of mind and body is the daily repetition of mantras. But there are a great many other practices as well.

Western aspirants of the contemplative arts are not unfamiliar with a variety of meditation techniques now available on the market. There’s Transcendental Meditation, Super Conscious Meditation, Sub Conscious Meditation, Raja Yoga Meditation, Bhakti Yoga Meditation, Karma Yoga Meditation, Initial Meditation, Intensive Meditation, Kundalini Meditation, Candlelight Meditation, Chakra Meditation, Yantra Meditation, Tantra Meditation, Vajra Meditation. Even as I am writing this article, the list keeps growing with more and more innovative titles. Some of these meditation techniques even have “patent” labels and trademarks. This is unheard of in India. Such yoga “products” carry a price tag, depending on the extent of the spiritual empire built up around them and investments made into their advertisement.

In moments of inspiration, would-be meditators dive into one or more of these practices with great enthusiasm. Many, however, give up almost immediately. Some conclude that such pursuits are just not for them. Others claim there is something wrong with their mantra or their method. Still others finally assert that meditation is just not a worthy activity. But if questioned they would all admit one thing: It’s not easy!

After sitting for some time in the first attempts at meditation, young enthusiasts find that their minds begin to wander and they become distracted. Perhaps they fall sleep. When this seems to become a pattern that may not improve, they begin worrying and wondering, “Is this working? Will it ever work? Am I making progress?” They start talking to friends who are trying to do the same thing. “Do you still meditate?” they ask. “Are you able to concentrate?” They conclude that although they were given some sort of technique–perhaps they spent a significant amount of money for it–they needed something more.

Those that arrive at this point might be surprised to learn that they have actually gotten off to a good start. They have realized that being still requires effort. This knowledge is a distinct gain. Most ordinary people would never have the opportunity to discover even this much.

Hundreds of years ago, one of India’s great Tamil saints said, “It is easy to tame the rogue elephant. It is easy to tie the mouth of a bear. It is easy to mount the back of a lion. It is easy to charm poisonous snakes. It is easy to conquer the celestial and the noncelestial realms. It is easy to trek the worlds invisible. It is easy to command the angelic heavens. It is easy to retain youth eternally. It is easy to enter the body of others. It is easy to walk on water and sit in burning fire. It is easy to attain all of the siddhis (yoga powers). But to remain still is very, very difficult indeed.”

To those earnest souls seeking the great stillness of yoga, I would ask, “What is the purpose and goal of meditation?” Without purpose and goal, there can be no meditation–or even concentration. Certainly, there is a deep soulful urge spurring us on, but that urge is usually so vague, so blurred in its outline, so difficult to confine within the four corners of a definition, that even its existence cannot be easily acknowledged. It is no wonder the mind succeeds in escaping all attempts at its mastery by a method so ill-defined.

The wise ones of ancient times can help us here. They assert that there is a one great Master Mind of which our individual minds are but a part. If such is the case, the obvious purpose of meditation is to achieve the goal of discovering this Master Mind. This is, indeed, the purpose and goal of meditation generally advocated by those who know.

There is a saying in my native Tamil language which translates roughly as follows: “Without concentrated practice, nothing tangible can be achieved.” Meditation is a long-term practice. Stillness of mind in the oneness of all is its crowning achievement.

We are less inclined to worry about the unsteadiness of our concentration when we realize that it is the nature of concentration to be unsteady. It might even seem at times that we do not possess a mind at all, but rather that a mind possesses us. The mind, it seems, has a mind of its own. Certain experiences just continue simultaneously without even asking our permission. A slight stomach ache. A small itch on the forehead or near the armpit. A burp. Obviously, the life processes of the body–like breathing and digestion–must keep going. Although this can be disconcerting for a beginner, the experienced meditator sits unwavering. After much practice, he finally begins to master concentration.

The mind in its natural state is steady. This natural state is not so far away. Look at little babies who with very little effort steady their attention on objects of attraction for long periods of time. Animals do this, too. It is natural. However, modern-day man lives a very complicated life. His concentration does not become easily fixed on any one thing for any length of time. He is just too busy. Yet, there are moments when he is completely absorbed. Perhaps a business problem demands his full attention–or a family tragedy, or a crisis with a friend. At some point everyone in every stratum of life experiences a steady mind resulting from focused attention. This focus of attention is the central theme of the Hindu religious discipline called sadhana. Sadhana is the road to the discovery of the Master Mind.

Well-trained yogis experience meditation as a state of being. This state of being can only rise up of its own accord and in its own timing–never by force. After we have made the effort of focusing our concentration in the consistent practice of sadhana, the deep stillness of perfect meditation will be difficult to resist. No one can claim to teach meditation and certainly no one should sell it like a commodity. It is not transferable in this way. It is each individual’s personal state of being himself.