BY MAITREYA HAWTHORNE

In his book Sadhana, Rabindranath Tagore relates an experience of meeting two Hindu ascetics. He asks them why they don’t go out into the world to preach the sacred word. One of the ascetics replies, “Whoever feels thirsty will of himself come to the river. They must come, one and all.” Certainly, through the years, thousands of such ready souls have flooded to the river of Tagore’s outpourings. Each could tell an entirely different story of his encounter with this man’s thought. One might be led to assume that anyone looking for anything could find something satisfying in the work of this divergent writer.

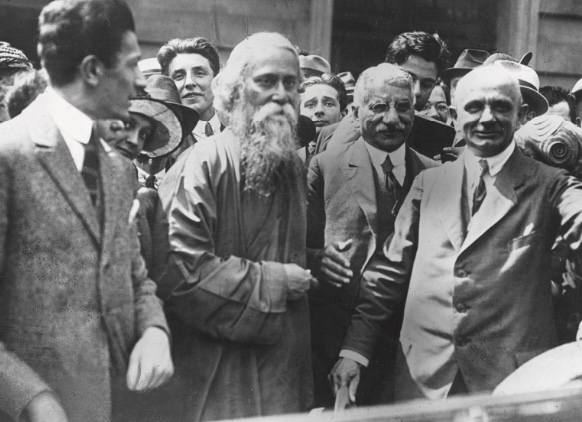

Tagore is indisputably acknowledged as the founder of modern literature in India, although he is perhaps most famous as the author of India’s unofficial national anthem. Yet, history waits to frame the greater legacy of this man, for the massive volume of his work continues to elude obvious categorization and full appreciation.

Tagore was born in 1861, the thirteenth child in a wealthy, Bengali brahmin family that was devoutly Hindu yet also strongly political. His father and grandfather were deeply involved with an emerging religious movement called the Brahmo Samaj (See sidebar). In this atmosphere, the precocious Rabindranath developed a fiercely individual perception of life from a young age.

As he begins to write, Tagore’s spiritual perspective is surprisingly difficult to pinpoint, for his thoughts on God, soul and divinity are more implied than explicit in the broader substance of his work, which is multi-faceted and sometimes abstract. In The Religion of Man, based on the Hibbert Lectures he delivered in 1930 at Harvard University, Tagore characterizes his own religious beliefs as ” & a poet’s religion & neither that of an orthodox man of piety nor that of a theologian.” The more we learn of Tagore and his work, the more we come to realize that access to his inner nature is vexedly labyrinthine, despite the prolificacy and profundity of his writings.

He was referred to as “the Indian Goethe ” by Albert Schweitzer, “the Great Sentinel ” by Mahatma Gandhi, and “Gurudev ” by his disciples. Writing was always a great source of inspiration for Tagore. His masterpiece, Rabisangeet, consisted of more than two thousand songs–all of which he wrote, recorded and sang. While he was revered as a guardian of tradition in Bengal–he recalls in The Religion of Man that, during his upanayana (coming-of-age, sacred thread ceremony) he experienced “a serene exaltation “–his religious beliefs were paradoxically unorthodox for his time. He was criticized by some for his efforts to reform Hinduism via the Brahmo Samaj movement, and introduce it to the West. Tagore felt that, with its postulation of monotheism, the Brahmo Samaj theology would be more palatable to Christians who might willingly embrace a pantheistic Hinduism.

In his writings, Tagore scarcely mentions the Puranas or the Bhagavad Gita, two popular scriptural texts often referred to by Hindus of his time. Instead, he focused primarily on man’s oneness with God. He was obviously influenced by the monism of the Upanishads. Again and again, he repeated that humanity’s mission on this physical plane is to merge with God. In Sadhana he states, “Man becomes perfect man, he attains his fullest expression, when his soul realizes itself in the Infinite being who is Avih, whose very essence is expression.” From Tagore’s perspective, man is constantly evolving, and divine union is his assured destination. “Religion only finds itself when it touches the Brahman in man, ” Tagore observes in The Religion of Man, “otherwise it has no reason to exist.” In Sadhana, he writes, “This is the ultimate end of man, to find the One which is in him, which is his truth, which is his soul; the key with which he opens the gate of the spiritual life.” Bits and pieces of his writings taken together outline his overall concept of man’s spiritual path, which might be summarized as follows: Life is man’s journey toward the realization of his fullest potential, which is union with God. That journey is best facilitated by the avoidance of worldly distraction.

Examples of the correlation between the Upanishads and Tagore’s writings are not hard to find. The Mundaka Upanishad states that “Like two golden birds perched on the selfsame tree, intimate friends, the ego and the Self, dwell in the same body.” In Sadhana Tagore writes, “When man’s consciousness is restricted only to the immediate vicinity of his human self, the deeper roots of his nature do not find their permanent soil. His greatness [is measured] by its bulk and not by its vital link with the infinite.”

In differentiating between earthly knowledge and sacred wisdom, Tagore again takes his cue from principles often repeated in the Upanishads. “[Man] has to discover that accumulation is not realization, ” he writes in Sadhana. “It is the inner light that reveals him, not outer things.”

Tagore considered man the highest of God’s creations. He writes, “The world has found its culmination in man, its best expression. Man, as a creation, represents the Creator.” Having asserted that man is divine, he describes his nature as having two aspects: the malleable ego and the eternal and permanent Self. “On the surface of our being, we have the ever-changing phases of the individual self, but in the depth there dwells the Eternal Spirit of human unity beyond our direct knowledge.” While he recognizes that man must strive to achieve perfection, he expresses his confidence that man is endowed with an inherent Divinity that assures his success.

His primary literary theme was man’s achievement of moksha, which is, according to Webster: “liberation from the cycle of rebirth impelled by the law of karma.” Rather than laboring in philosophical analysis, Tagore’s writings amplified the devotional inspiration of surrendering to God and serving humanity with love. Even his political views were deeply influenced by this poetic and devotional view of life.

There is a notable thread of soul-bearing honesty running through his work. Although he affirms his belief in reincarnation as “a history of constant regeneration, a series of fresh beginnings, ” he also writes in The Religion of Man that, “All I feel from religion is from vision and not from knowledge. Frankly, I acknowledge that I cannot satisfactorily answer any questions about what happens after death.”

Much of Tagore’s religious inspiration came from nature. It was nature that gave his poetry its ethereal beauty. Gitanjali, one of his best-known works, for which he won the 1913 Nobel Prize for Literature, is a poem celebrating the nature worship of his “Vedic ancestors.” This work, so lofty in its abstract worship, also revels his deep patriotism to India. In one of Gitanjali’s most popular passages, Verse 35, Tagore’s blends his deep love of country with his faith in God.

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high; Where knowledge is free; Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls; Where words come out from the depth of truth; Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection; Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit; Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

This verse is particularly revealing of Tagore’s devotional love for his homeland. It focuses less on what India is than what it can become. Similarly, Tagore defines his religious beliefs more by what they are not than what they are. Yet his beliefs, both patriotic and religious, are never without a fundamental faith in a personal God and the role He plays in leading India toward a better life that Tagore also hopes might be possible for all of mankind.

Tagore’s patriotism was paradoxical. While he clearly loved his country, he was sharply critical of nationalists. This provoked controversy for him in his native Bengal. His novel, The Home and the World, was dismissed by critics as “immoral and unpatriotic ” because it characterized Sandip, a Bengali revolutionary leader, as a fanatic, a womanizer and a hypocrite. In Rabindranath Tagore: An Anthology, editors Krishna Dutta and Andrew Robinson write, “The ‘home’ and the ‘world’ referred to his own mind divided against itself to India versus Britain, to the East versus the West & ” Tagore was also occasionally reviled as an Anglophile and disrespected for being a brahmin with a wealthy, elite background.

Tagore was a man committed to ideals that were not popular during his lifetime, such as female emancipation and freedom of individual expression. He suffered much condemnation for investigating these issues publicly, via his writing. The political tensions created from this must have troubled him deeply. Yet he did not waver.

In 1901, Tagore founded a school for children in a place called Santiniketan, which means “Abode of Peace.” Eventually, it became a university, which he named Visva-Bharati. He envisioned Visva-Bharati as a place where the East could meet the West. To commemorate this sentiment, he chose a Sanskrit verse for the school’s motto: “Yatra visvam bhavatieka nidam, ” meaning, “Where the whole world meets in a single nest.” In 1863, he founded an ashram in the same place.

Tagore believed that a poet of singular vision could earn his rightful place among saints and sages. In Galpaguchha, he writes, “Like the Supreme Creator, he [the poet], too, creates his work out of his own self.”

Through his abundant writings, Tagore gave his all. And for that, he earned a permanent place in the history of India. No one has stepped forward to match the thought-provoking effect he had on his cherished homeland. No one in the recent history of Bharat has ever written so broadly, so deeply, so fearlessly–yet so spiritually–that he could be extolled and remembered as “the myriad-minded man.”

Maitreya Hawthorne is a graduate student in English at Sonoma State University in California, where she is writing her thesis on Rabindranath Tagore.

THE BRAHMO SAMAJ: AN ABBREVIATED SUMMARY OF PRINCIPLES

Followers shall worship the One Absolute Parambrahma.

Followers shall not adore any created thing, thinking it to be the Supreme One.

Followers should serve God by performing good deeds.

He is the One, Alone and Absolute.

The Samaj is to be a meeting ground for all sects for the worship of the One True God.

No object of worship or set of men shall be reviled.

No graven image shall be admitted.

No object animate or inanimate shall be worshiped.

No sacrifice is permitted.

Promote charity, morality, piety, benevolence and virtue, and strengthen the bonds of union between men of all religions and creeds.

A BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF A SAGE AMONG POETS

Born in Calcutta, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) received his earliest education at home within the warm embrace of a large, wealthy, extended family. Although his father wanted him to be a barrister and sent him to law school in England when he was 17, young Rabindranath did not finish his studies there. Instead, he returned to India where he slowly accrued moderate success in Calcutta as a writer, playwright, songwriter, poet and philosopher. As he got older, he helped manage the family estates, a role which kept him in touch with common humanity and increased his interest in social reforms. In 1883, Tagore married Mrinalini Devi Raichaudhuri, with whom he had two sons and three daughters.

Rabindranath’s father was a leader of the Brahmo Samaj, a religious movement formed in 1928 to revive the monistic teachings of the Upanishads as a fundamental basis of Hinduism. Although clearly influenced by the thinking of his father, he was–first and foremost–an artist. He occasionally delved into Indian politics and was a close friend of Mahatma Gandhi. He was opposed to nationalism and militarism as a matter of principle and chose to deal with the social and political challenges of the times by supporting and promoting spiritual values. His dream was to create a new world culture founded on diversity, tolerance and multi-culturalism.

Tagore’s life changed dramatically in 1912, when at 51 he returned to England for the first time in 35 years. He made this journey by boat and used the lazy hours at sea to translate his latest selection of poems, entitled Gitanjali, into English. Until then, he had authored his works only in his native tongue of Bengali. This was his first attempt at translation. In England, a friend of his–a famous artist he had met in India named Rothenstein–learned of the translation and asked to see it. Reluctantly, and only after much persuasion, Tagore let him have a look. Rothenstein loved the work and showed it to his friend, the world-famous William Butler Yeats. Yeats was enthralled and later wrote an introduction to the collection of poems when it was published in September, 1912, by the India Society in London. The rest is history. Tagore was an instant sensation, first in London literary circles, and soon after that, around the world. Less than a year later, he received the Nobel Prize for literature. He was the first non-Westerner to be so honored. In 1915, he was knighted by the British King George V, but soon renounced this honor in protest when the British massacred 400 Indian demonstrators in Amritsar.

Today, Rabindranath Tagore is considered India’s greatest literary figure. The variety, quality and quantity of his work is colossal. He wrote over one thousand poems; eight volumes of short stories; nearly two dozen plays; eight novels; and hundreds of essays on philosophy, religion, education and society. He also composed more than two thousand songs–both the music and the lyrics. Two of these became unofficial national anthems for India and Bangladesh. When this prolific maestro reached the ripe age of 70 and his friends assumed he would wind down in his sunset years, he took up oil painting, achieving critical acclaim all over again in yet another creative genre. At the age of 80, he passed away peacefully in the house of his birth.