PHOTOGRAPHED AND REPORTED BY DEVRAJ AGARWAL, DEHRADUN

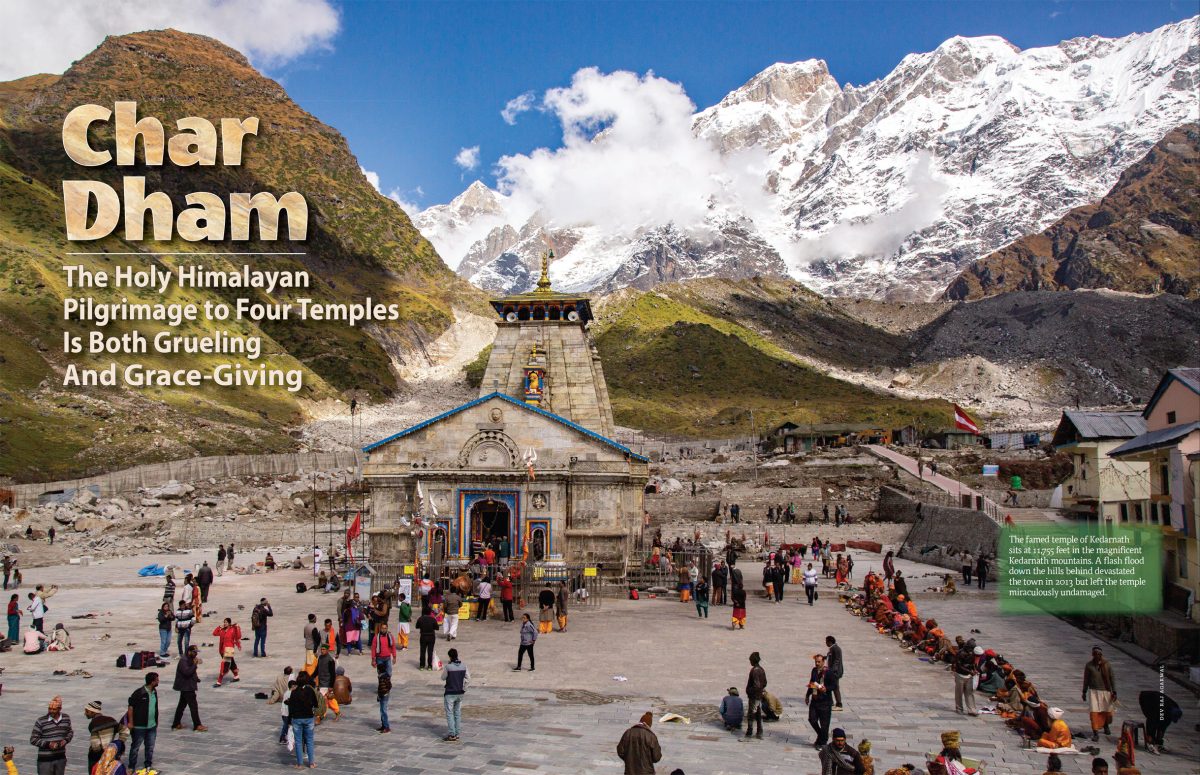

THE CHAR DHAM PILGRIMAGE of India’s Uttarakhand state attracts nearly a million pilgrims a year to all or some of four remote Himalayan temples: Yamunotri, Gangotri, Kedarnath and Badrinath. The official name, Chota Char Dham (literally, “small four abodes”), distinguishes this pilgrimage from the Char Dham of greater India, which includes Badrinath, Dwarka on India’s western coast, Puri on the eastern and Rameshwaram at the southern tip.

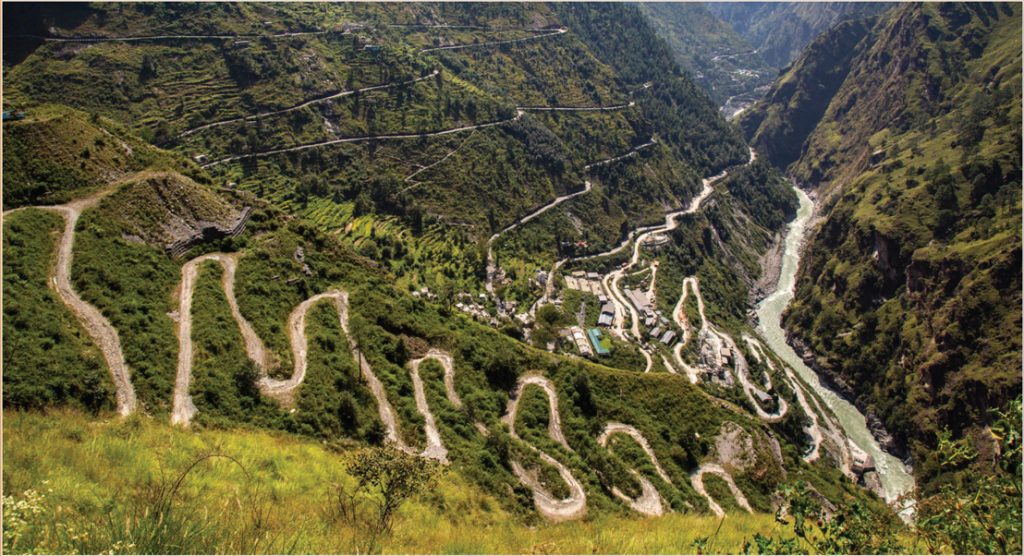

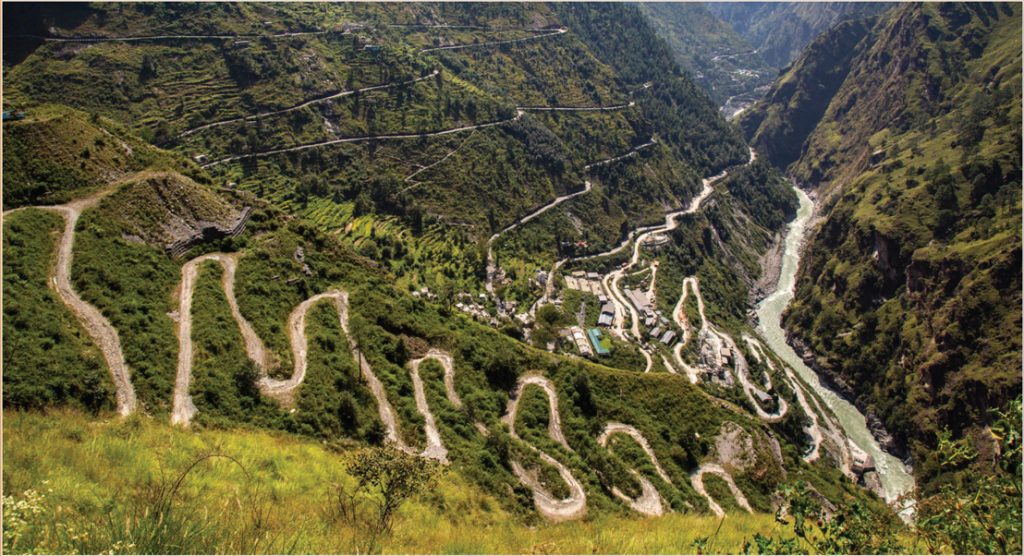

Though its overall distance is relatively short, the Chota Char Dham pilgrimage was arduous until modern times. The high Himalayan paths, snowy and icy even in summertime, deterred all but the bravest; most pilgrims were sadhus. Even today, only Badrinath and Gangotri can be reached by road. Yamunotri is a three-hour hike from the end of the road; and Kedarnath, especially since the 2013 floods, is a grueling all-day trek—or for the less adventuresome, a five-minute helicopter ride.

The Indian government has initiated an ambitious US$ 1.7 billion project to build an all-weather road system connecting the temples to main highways at lower elevation. The work is well underway, and one periodically encounters road sections under construction. An even more ambitious $6 billion rail project is in the planning stages; this will match developments on the Chinese side of the border. Both projects will improve military access to areas near the disputed border.

Fortunately for pilgrims, the existing roads are adequate. Strategic border issues are driven from the mind by the overwhelming beauty of the Himalayas, so wonderfully summarized centuries ago in the Skanda Purana: “In a hundred ages of the Gods, I could not tell you the glories of the Himalayas. As the dew is dried up by the morning sun, so are the sins of mankind by the sight of the Himalayas.”

My home is in Dehradun, on the route to Yamunotri. I can personally attest that the land of Char Dham reverberates with the spirituality that led sages and saints to choose these remote regions to find solace, explore mountains, forests and river valleys, and perform sadhana in their search for Self Realization. They meditated in caves, temples, monasteries and temporary shelters. As part of this holy environment, they ventured to these four sacred temples.

Uttarakhand has a natural border, formed by the snow-covered mountains of the main chain of the Himalayas. To the north is China, to the east, Nepal. Famed for its picturesque valleys and forests, the state is flanked by the holy Yamuna River in the west, close to Himachal Pradesh, and the main branches of the Ganga in the east—the Bhagirathi, Mandakini and Alaknanda. The four temple are situated in the high valleys of these rivers, close to the tree line, around 10,000-foot elevation.

The pilgrimage starts at Haridwar, where the Ganga enters the plains of north India. Earlier, the Char Dham journey began with blessings from the Maharaja of Tehri, considered in these regions an avatar of Lord Vishnu and protector of the four temples.

Until modern times, the four temples were inaccessible in winter, and the Deities were temporarily moved to lower “winter homes.” The tradition continues to this day, even though one can now reach the higher temples throughout the year. There have been recent proposals to keep the Deities at the higher temples, but the temple priests oppose such a change.

Before the 20th century, the Char Dham pilgrimage was a major challenge. There were no roads or proper bridges. It took months to make the journey. In a few stretches we trace the ancient track to Char Dham, which is still used by some sadhus who perform the holy pilgrimage on foot. The old route ran east to west, crossing up and over the high mountain ranges and alpine meadows of sublime beauty. Today’s roads follow the river valleys and are much longer in distance.

The arduous trek to the first temple: Yamunotri

Char Dham Routes and Yamunotri Temple

We have a historical account of this sadhu route in the biography of Bhagwan Swaminarayan (1781-1830) who established the Swaminarayan Sampradaya. He renounced his home at the age of 11 and embarked on a seven-year spiritual journey across India, three years of which were in the Himalayas. He arrived at Kedarnath at the onset of winter in 1792, took darshan of the famous Jyotir lingam, then trekked to Badrinath. He crossed glacier after glacier and traversed deep gorges, covering approximately 80 miles in nine days. Without maps, food or money, wearing nothing but a loincloth around his waist and completely alone, he navigated the treacherous terrain at heights of more than 19,000 feet and survived temperatures that plummeted to -20° C (-4° F). It was the rare sadhu who attempted this route.

In more recent times, ashrams and affluent people have built modest hostels along these high routes and laid paved paths in places. Thirty years ago I spent a numbingly cold night with sadhus at such a facility at Panwali Kantha in Tehri Gharwal. Hardly any sign is visible of that noble yatra now.

Assigned by HINDUISM TODAY to photograph and report on the Char Dham pilgrimage, I depart Dehra Dun on September 22, 2018, late enough in the year to hopefully avoid the monsoon rains but before the temples would close for winter a few weeks later.

On the Way to Yamunotri

Traveling about 37 miles across the Mussorie Hills from Dehra Dun I reach the wide valley of the Yamuna River, a tributary of the Ganga. Though not many miles from the Bhagirathi and other tributaries, Yamuna travels another 800-plus miles south, passing through Delhi, before joining Ganga at Prayagraj.

The picturesque valley is away from main highways, uncrowded and with few facilities until one reaches the small town of Barkot, 40 miles upstream. Hotels and restaurants here accommodate pilgrims who stop for the night and reach Yamunotri the next day.

It rains all night, and the morning is cold. I take a lovely drive along the meandering river. The valley is dotted with rustic hill villages still insulated from the onslaught of modernization. As we gain elevation, the vegetation changes abruptly, with firs and rhododendrons testifying to the altitude. The monsoon rains have created hundreds of waterfalls along the valley sides.

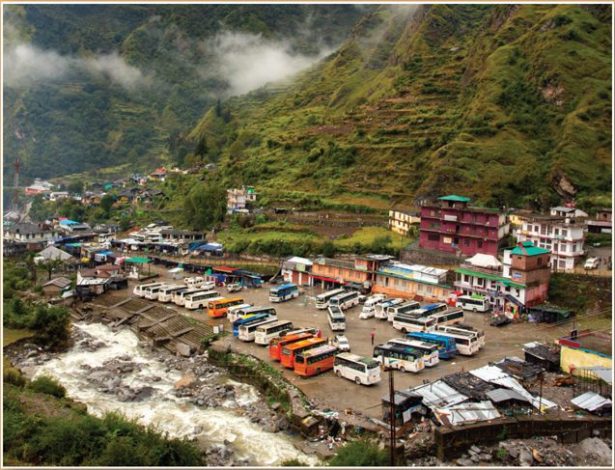

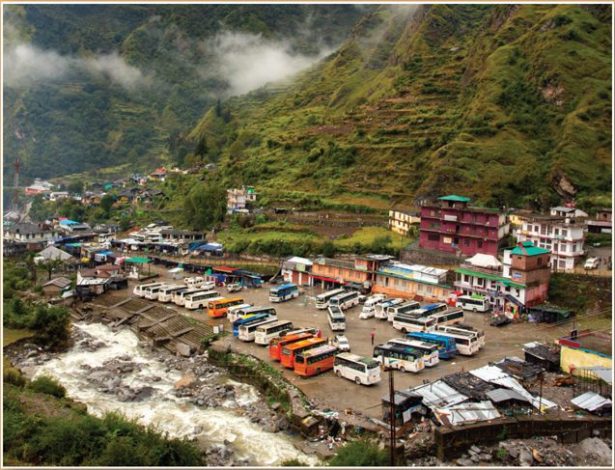

An unexpected late-September spell of rain had changed everything in Yamunotri valley. The landslide at Syanachatti went active the day before our arrival, blocking the road and forcing hundreds of pilgrims to spend the night on the road, drenched, hungry and stranded. Earth-moving equipment, permanently stationed nearby, has the road opened by morning, so we are only slightly delayed. But the number of pilgrims arriving at Janki Chatti, the small, ill-kempt town at the end of the road, is double normal. Pilgrims proceed on foot or by mule from a huge parking lot. Porters will carry the old and infirm in a palki strapped to their back, a method that is hazardous for both porter and pilgrim, should there be a slip.

Those who can walk leave without a second thought, while others bargain with porters, mules and palki providers. Prices suddenly go up, and pilgrims grimace at the extra burden on their meager budgets.

The sun shines briefly but fails to warm the valley. The rain continues. I had planned to hike to the temple, but since I am running late, I decide to take a pony—at a price three times higher than the regular charges—in order to get back to Barkot by evening.

The ride is beautiful, with giant conifers flourishing in the narrow valley. The regular path along the riverbank has been washed out by recent rains, forcing pilgrims to negotiate an alternate route with very steep and slippery sections, with no railings to hold on to. A few young officers of the Uttarakhand Police help those who need assistance. I reach the temple, at an elevation of 10,797 feet, in an hour and a half, soaking wet.

Men and women are gathered in clusters at the temple, some coming our of the crowded hot water pool, some changing their clothes in the small shed, all, struggling to keep belongings dry. It all seems barely manageable in the tight space.

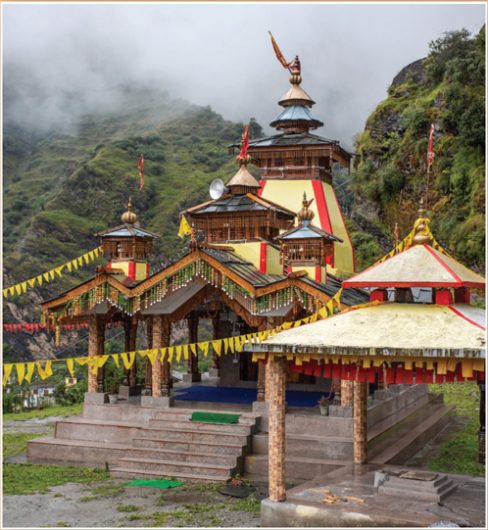

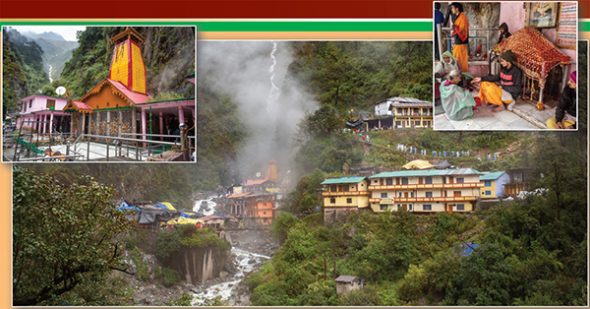

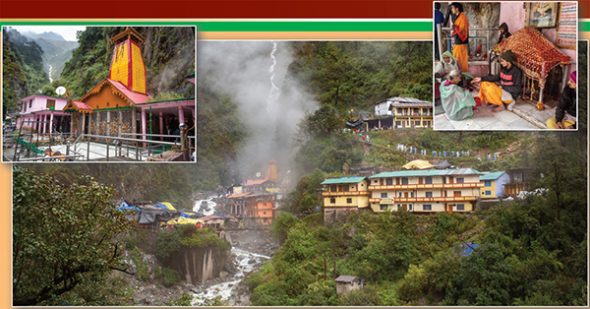

The present Yamunotri temple was constructed by the Maharani of Jaipur in the late nineteenth century. The main object of worship, visited by all pilgrims, is the Divya Shila, a small stone representing the Goddess Yamuna. It is enshrined just outside the temple.

The main prasad is rice cooked in small packets in the boiling hot water of the thermal spring called Surya Kund, which also supplies the hot water for a pool where pilgrims take a dip. As at the other Char Dham temples, many pilgrims make offerings to their ancestors.

Overall, the facilities here could be greatly improved, especially in comparison to the other three temples of the pilgrimage. Pundit Pradeep Uniyal, one of the priests, compares living here to living in the sixteenth century. “The government is absolutely negligent about the development of Yamunotri.” For example, nobody from the government came here after the floods in July washed away four shops and some of the bathing ghats.

I return to Barkot in the evening, just before the Syanachatti landslide area again becomes impassable, leaving pilgrims stranded on both sides. At Barkot I meet four Gujarati families from Mumbai who have also just returned from Yamunotri. Rajul Patel mentions he was a bit dejected by the experience, “Holy places should be holy places and not business places. The dirty and disorganised Yamunotri left a sour taste. We should instill in our children love for our culture, holy places and value system.”

Onward to Gangotri

I proceed from Barkot the next morning. Nourished by the monsoon rains, the mountainsides wear a glistening blanket of fresh green grass. As we head eastwards, the winding road passes through spectacular pine forests, then enters the Bhagirathi River valley and passes through Uttarkashi, “Kashi of the North,” one of many sacred places and river confluences along the Char Dham route. Uttarkashi is a must for many pilgrims and has lots of good hotels and ashrams. We travel north past Gangnani, with its popular sulfur springs. About 43 miles from Uttarkashi, the valley opens up into a famous apple-growing region started by Frederick Wilson, a British soldier who deserted following the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857 and sought refuge here. We stop for the night at Harsil, just below the rustic village of Mukhwa, winter seat of Gangotri. The temple, a replica of Gangotri, is reached across a small suspension bridge. Further up is a similar temple, Markandeyapuri, the seat of Goddess Annapurna, who comes down with Ganga for the winter.

At Bhironghati, we stop at the tea shop of Mathura Prasad, who started his business here 45 years ago. The unexpectedly sagacious chaiwala shared his observations on the changing face of the yatra over the years: “Most of the visitors come for fun now. Yatra is just a little part of their itinerary. Days of poor pilgrims carrying their belongings on the head and surviving on sattu [a mix of ground barley, chickpeas, sugar and salt] are gone. The yatra took months back then, and you either braved the ordeals of the journey and made it home, or just perished. That was a true yatra.”

Bhaironghati is at the junction of two roads: one leads to Gangotri, just nine kilometers to the east, and the other north to Nelang Valley, from where one can enter Himachal Pradesh or Tibet. This was a popular trade route before the Chinese aggression of 1962. Judging by temple statues and artwork, I believe many artisans and laborers must have come from Tibet to work on the temples of Garhwal along such routes. For example, in many places the face of Lord Siva resembles that of Buddha.

One is again and again overwhelmed by the sheer beauty of the mountains. As I approach Gangotri, the still-distant 21,000-foot Sudarshan Parvat stands like a tower far ahead, looming above the giant conifers nearby. I cannot resist the temptation to go down to the thundering Suryakund waterfall before visiting the temple. What a soul-stirring sight it is to watch the surging water of the Bhagirathi falling abruptly into a giant crater. The resulting noise and vibrations are beyond words.

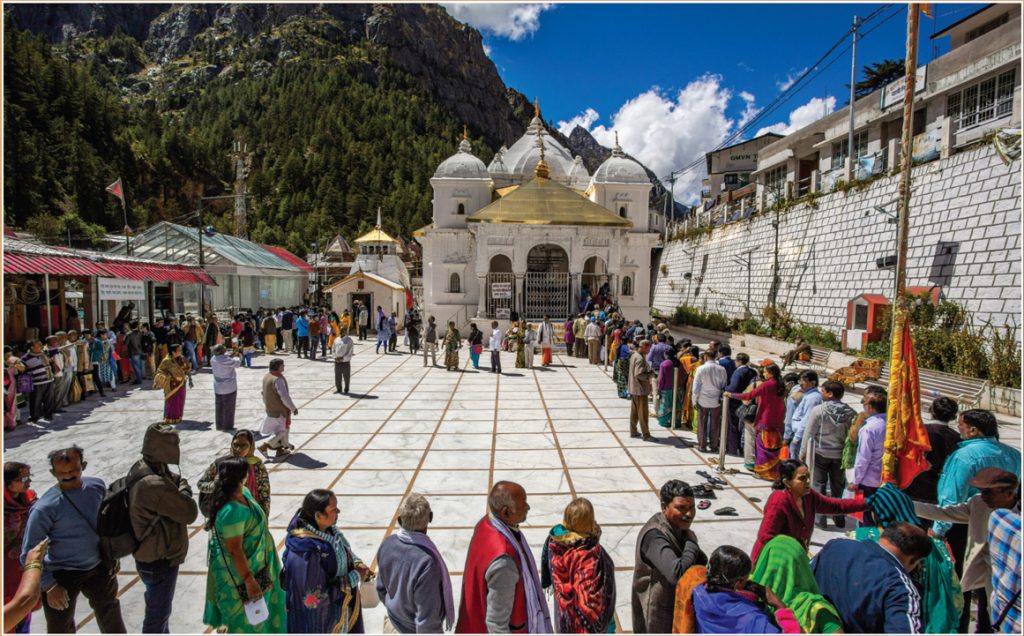

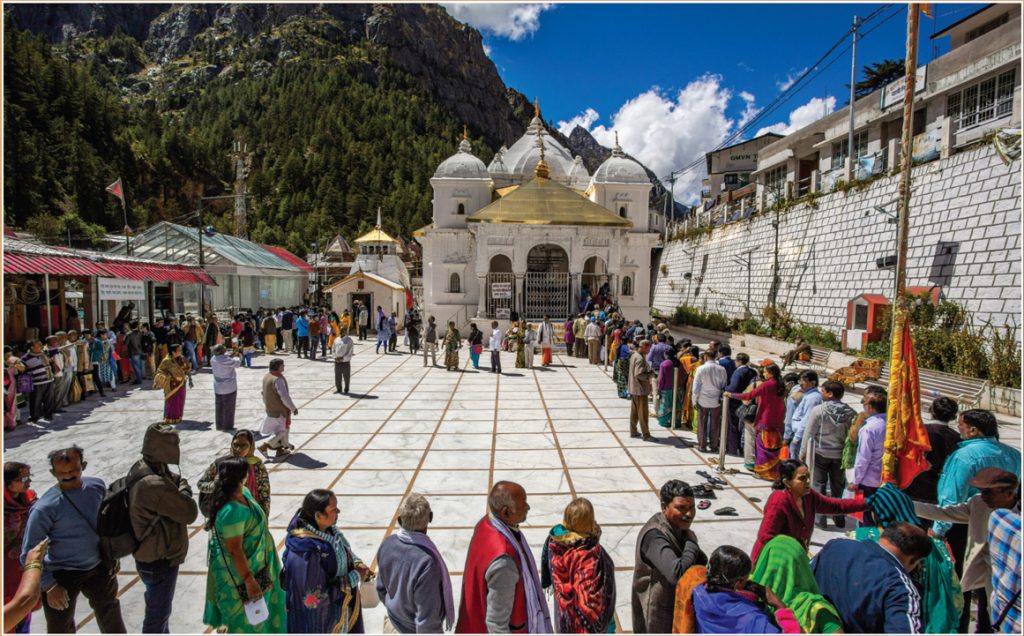

The present temple of Gangotri was constructed by a Gorkha commander named Amar Singh Thapa in the early eighteenth century. The banks of the river have all been turned into walls of concrete. Platforms used by pilgrims for rituals flank the river for quite a distance.

This temple lacks the intricate artwork and pillars we often see in older temples of the Himalayas, but it is beautifully constructed. The sanctum sanctorum enshrines majestic display of five murtis: Ma Ganga, flanked by Durga, Lakshmi, Annapurna and Saraswati. Also enshrined here are murtis of Bhagirathi, Yamuna, Jahnavi and Ganesh.

The crowd swells as the day progresses. A long queue of pilgrims is systematically moving towards the temple for darshan, managed competently by a few young women officers of the Uttarakhand Police.

Groups of pilgrims sit on the river bank, against the backdrop of Sudarshan Parvat. A group of 32 from Chhattisgarh state in central India are busy in a collective ritual of pindaan, food offerings to their ancestors. Even though the weather had prevented them from visiting Yamunotri, their focus is on gratitude. One of them, Lachchhi Ram Rathore, expresses this beautifully: “The blessings of our ancestors brought us here. What a feeling of joy it was to offer pindaan to them. I felt as if I was sitting in heaven.”

Pundit Ganesh Semwal, the pujari and the Joint Secretary of the Temple Committee, tells me the tradition at Gangotri Dham is to have local Teertha Purohits instead of the Ravals usually brought from South India. Their priests hail from the Semwal families of Mukhwa, the winter abode of Ma Ganga.

Gangotri, Near the Headwaters of the River Ganga

ALL PHOTOS: DEVRAJ AGARWAL

Honoring Ancestors

I am captivated by a bus with Nepal plates beside the road. The leader, Kailash Thapa, is taking 27 pilgrims on a months-long pilgrimage to holy cities across North India for just $208, which includes two meals a day. The pilgrims could either pay to spend the night in a hotel or sleep on the bus for free. Thousands of such economy buses from all corners of India bring pilgrims on Char Dham Yatra, but mostly during the hot, dry May-June season.

I return to Harsil from Gangotri the same day, spend the night and move on toward Kedarnath. This time I stop longer at Uttarkashi to visit its fabled Kashi Vishvanath Temple, which stands in the middle of a large complex dotted with smaller temples, all wearing a modern look. I sit on a bench for more than thirty minutes, lost in listening to the Siva Mahima Stotram. Mahant Jayendra Puri, the chief priest, tells me it was predicted in the Skanda Purana that Lord Siva would establish a second Kashi in Uttarakhand, which would be known as Uttarkashi. The queue of devotees is almost unending till nightfall.

The Road to Kedarnath

Thanks to the all-weather-road project, the day’s travel is quick—130 miles in just seven hours. The route takes us along the Tehri dam and reservoir until we intersect the road that goes from Rishikesh to Badrinath, last of the Char Dham temples. We take the route to Guptkashi and Phata, where there are many resorts and helicopter companies.

The original 7.5-mile path to Kedarnath, which followed the right bank of the Mandakini River, was totally washed away by disastrous floods in 2013 that killed thousands. A new path is being constructed on modern lines along the left bank, with all kinds of facilities along the way. It is operational already, more than half of it paved with stone slabs and concrete, but longer by a mile or more and much steeper. Many pilgrims are disheartened to realize the trek to the temple can take a full eight hours.

More than ten private helicopter companies ply the route between Kedarnath and Phata, offering a five-minute flight and a spectacular view for a one-way fare of about US$55. The demand for this service, used now by perhaps a quarter of pilgrims, has risen since the trek has become more difficult.

Things feel different as I get down at the helipad in Kedarnath. It is not just the crowd of pilgrims, but the spirit with which they walk, chanting “Jai Baba Kedar!” Somebody once told me you can feel the presence of Siva in Kedarnath. That is certainly true today!

There is no other temple like Kedarnath, literally “The Powerful Lord.” The spiritual presence of the Himalayas makes it so special. Perhaps this is the reason Lord Siva chose it as a favored place. The stone temple stands against the massive glaciers and high snow peaks of Kedarnath range. Lucky pilgrims see these natural wonders in all their grandeur when the weather is clear, as it was for me today.

The area is much changed now, five years after torrential rains unleased a massive flood from a glacial lake a thousand feet above the temple. Water swept through the town at 25 mph—that’s 36 feet per second. Within minutes the flood was over, leaving the town destroyed and bodies everywhere. Downstream there was even greater damage and death. But Kedarnath Temple itself was untouched, protected by a huge boulder (now an object of worship) which lodged behind it, splitting the flood waters to both sides. Rebuilding efforts have proceeded nonstop since 2013.

The main entrance to the temple is called the Mahadwar. The first section of the huge building is the Sabha Mandap, where a brass Nandi sits on the stone floor. The statues of Veerabhadra, Bhrangi, the Pandavas (said to have come here) and Lakshmi Narayan adorn this hall. The walls and intricately carved massive pillars are all black and shiny, coated with soot, oil and ghee over the years.

The middle section of the temple is Himgiri, where murtis of Ma Bhagwati, Ganesha and His consorts, Riddhi (Prosperity) and Siddhi (Spirituality), are housed. In the third section, the sanctum sanctorum, is Siva as a natural rock Sivalingam, the main object of worship here. Everyone looked overwhelmed and tears of joy, contentment and attainment flowed down the cheeks of many. Surely, it is difficult to contain one’s emotions in a place like Kedarnath, for Siva lives here in person, many believe. Here, unlike most temples, one can touch the Sivalingam.

Braving the chilly wind on the cold floor in the courtyard, many pilgrims perform family rituals before entering the temple. But the balmy sun and the divine view of the Kedarnath peak do not last long. With the arrival of colder winds and gathering clouds, pilgrims start to disperse—some to the helipad, most to hike back down to the roadhead.

Kedarnath township is a busy construction site, with masons, carpenters and laborers working day and night to return it to its pristine glory. Buildings, bridges, roads and embankments are all under construction simultaneously, all day and night, year around.

The Grand Route to Kedarnath Temple

I take the opportunity to climb up to the Bhairav Temple. From here, one has a commanding view of the town against the backdrop of the valley, with the Kedarnath peak towering above the northern horizon. But the extravagant display of divinity and nature is short-lived: in a minute, the entire valley is engulfed with clouds and fog so thick that visibility is reduced to a few meters. Sudden rain and sleet force me to turn back, seeking a safe shortcut down to the hotel.

The weather has grounded the helicopters, and I retreat to the town’s single hotel, the Garhwal Mandal Vikas Nigam, where I meet N. Subba Rao of Bangalore and his group. He has traveled widely in mountains, including Kailash and Mansarovar in Tibet, and always wished to undertake the Char Dham pilgrimage. “We cannot explain how we feel here, for it is too special and personal to be explained. I get energy from mountains. I am more calm and patient after coming here.”

Lalita Sivaswami from the group appreciates the discipline and orderly running of the yatra on Kedarnath circuit. “Prices are fixed and the panchayat, the local body looking after the yatra arrangement and convenience of pilgrims, very kindly ascertains and suggests what one should hire—a porter, pony or a palki—considering the age and health of the various pilgrims. I came here for Char Dham, not for mountains. If Bhagwan calls me, I will come back for the yatra again.”

Praddyuman, a young boy in the group, is here for the love of mountains; for him, the pilgrimage is a bonus.

The night’s cold is unbearable, and the construction noises keep me awake until midnight. More pilgrims arrive in the morning, having taken a bus from Haridwar, at $35 each. They had been forced to stop the trek up about a mile short of Kedarnath the previous afternoon. They had been able to hire expensive bedding, but had slept without supper. Dhoman Kushwaha, the group’s leader, says the darshan of Ma Yamuna and Ganga have compensated for that. Jayashree Thakur expresses concern for the palki carriers; one had fallen while carrying a pilgrim and injured himself. “Our ministers should come here, walking, and see under what conditions men work in this difficult terrain.” Her niece, Deepa Trivedi, feels the presence of Siva here. “Siva saves you from ordeals. He saved us yesterday and helped us reach here. You feel purity here.”

Most who fly in by helicopter return the same way, but I opt to hike back down to Gaurikund. There are tea shops, rest shelters and other arrangements for pilgrims at short intervals. Traffic is controlled, and the porters, ponywallas and palkis are organized and polite. Initially there are almost no signs of the 2013 floods, but as the valley becomes narrower and the track runs closer to the river, we can see large landslides and washed-out embankments left by the disastrous floods. Parts of the old track on the right bank are still visible, but surely beyond hope of repair. It took me three and a half hours to reach Gaurikund, which by that time was almost deserted, the next group of pilgrims having either airlifted to Kedarnath or begun their trek up.

Off to Badrinath

I return to Guptkashi for the night and then leave in the morning for Badrinath, the last temple of the Char Dham. The shortest route is to take the forest road to Gopeshwar. On the way is the small town of Okhimath which houses the Omkareshwar Temple, winter seat of Kedarnath. The road from here passes through some of the most spectacular alpine forests of the Himalayas, and the area of Chopta is aptly called the “cradle of the Himalayan flora and fauna.” These forests are home to bears, leopards, the rare Himalayan Thar (a relative of the mountain goat), the bharal or Himalayan blue sheep and that most exotic of mountain birds, the spectacularly iridescent blue monal, which I was lucky to have photographed on an earlier trek in this region.

Just before reaching Chopta, one can see the old Char Dham pilgrims’ track and a now-abandoned dharmasala for sa dhus which was active up to twenty years ago. Many Char Dham pilgrims opt for the one-hour trek from Chopta town through picturesque alpine meadows dotted with rhododendrons and firs to reach Tungnath Temple, the highest of the Siva temples.

Traversing the Rugged Himalayas

Lord Vishnu’s Mountain Home on the Alaknanda

Another Siva temple, apparently contemporary with Kedarnath, is located in Gopeshwar, near the Alaknanda River. In the courtyard stands a giant trident inscribed in a language yet to be deciphered, along with many other murtis.

Two hours away is Joshimath, where Adi Shankaracharya is said to have attained enlightenment under the giant mulberry tree. The Narsingh Temple here is called the winter seat of Badrinath, but the main murti of Lord Vishnu remains there throughout the year. Only the seat of Shankaracharya is sent down in winter. Two other murtis—Uddhav, a friend of Krishna’s, and Kubera, God of Wealth—are sent down to the village of Pandukeshwar, about 20 km closer to Badrinath.

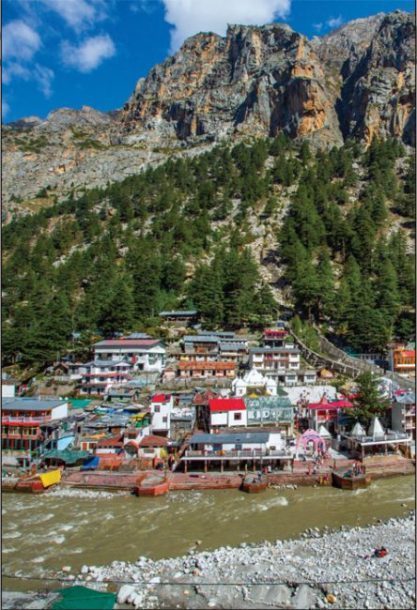

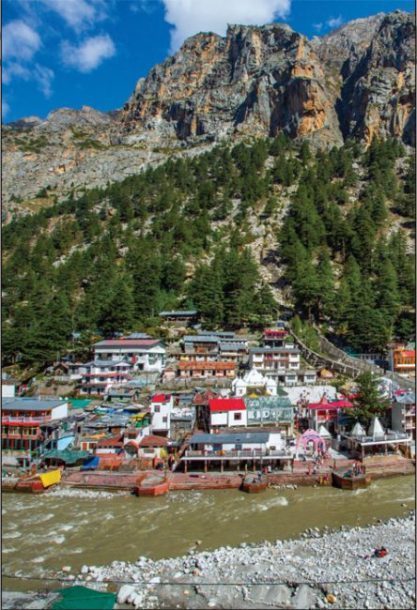

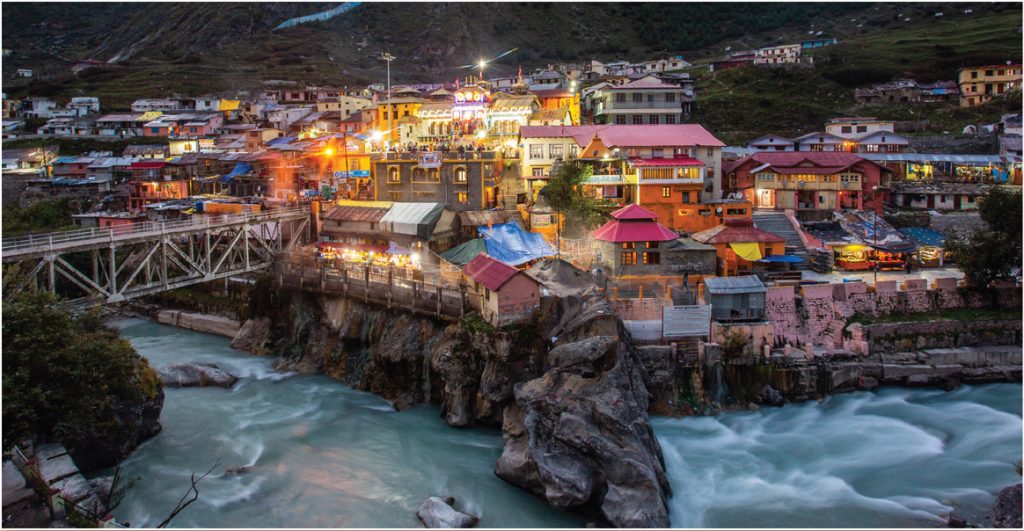

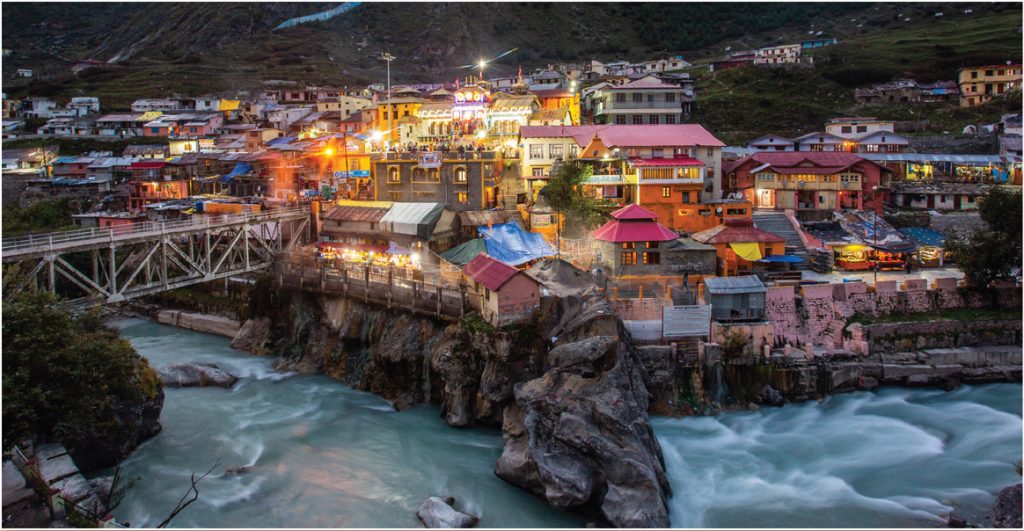

We soon approach the tree line and then arrive at the small plateau upon which Badrinath sits with the majestic Neelkanth Mountain behind it. This temple, one of the most prominent for Vaishnava Hindus, is at least a thousand years old. It is said that a fully carved statue of Lord Vishnu, who is worshiped here as Badrinarayan, was discovered by Shankaracharya in the ninth century at Narad Kund and relocated to this site. The temple is unique in that it has a painted facade and is covered from all sides. Its resemblance to a Buddhist shrine leads some to believe it was once a Buddhist temple; but to me, the architecture of the temple is typically Hindu. As mentioned earlier, many medieval temples and statues in North India have Buddhist influence on them—probably because of their close proximity to Tibetan artisans. It was closer and easier to hire labor from across the border than to bring people from the plains of India, especially since there was no road access to Badrinath before 1965.

The pillars of the temple are massive and intricately decorated. The main statue, inside the central sanctum, is that of Lord Vishnu in standing position holding His conch and chakra in two of His four hands. Also housed here are murtis of Uddhav, Kuber, Narada, Lakshmi, Garuda, Navdurga and others.

The town, loaded with pilgrim facilities, pulses with life and religious fervor. The wish to perform tarpan, offerings of water from a sacred river to the ancestors, is the chief cause for visiting Badrinath. I happen to be here during the fortnight of pitrapaksha, the time to honor ancestors, which falls in late September each year. The bathing ghats are packed with groups of pilgrims performing tarpan. Priests from all areas of India are helping perform the rituals for those coming from their regions.

Before any ritual, pilgrims take a bath in Taptkund, the sulphur springs below the temple. After the bath, many pilgrims observe the ritual of pindaan by the river before entering the temple, while some directly perform their puja inside the temple. The daily rituals inside the four temples begin early in the morning and last till late evening, when arati is performed.

Ishwar Prasad Namboodri, the young and energetic Rawal of Badrinath, has the vision of a modern planner. He is concerned about cleanliness, health, sanitation and safety of pilgrims. At the same time, he is skeptical about the hasty way many pilgrims perform rituals. He laments the use of plastic plates and plastic flowers, feeling we should make our offerings on plates made of leaves and adorn our Gods with natural flowers.

For many, the pilgrimage is a spiritual attainment not easily described in words. Sandeep Badham, a businessman from Barabanki, Uttar Pradeshm, is here in a group of four families. They had come on Char Dham Yatra in 2013, and just escaped the Kedarnath flood. “It was the sheer blessings of the Gods that saved our lives. We returned home without darshan, so here we are once again. This time we have performed all the rituals at all four shrines. I have gotten everything I ever aspired for. What I have received could not be bough anywhere. I hope the next generation of my family follows in my footsteps.”

My own pilgrimage to Char Dham ends with that inspiring interview. The 300-km return trip through Rishikesh is completed in just a day, and I am back home.

Closing Badrinath for the Winter

A few weeks after my return home, I find these Himalayan temples are not quite finished with me: the opportunity arises to attend the closing of Badrinatha Temple for the winter. This is a spectacular and exciting event, made even more so by the presence of Swami Avdheshanand, head of Juna Akhara, and the multifaceted Swami Ramdev, two of the most popular swamis in India, who came unannounced to join the worship out of their love of the God here (see page 13 for their kind words about HINDUISM TODAY).

The Char Dham temples have the tradition of six months of nar puja, worship by humans, and six months of Narayan puja, worship by the Gods. This likely started because weather constraints made the higher reaches of Uttarakhand inaccessible in winter.

On my way to Badrinath, I have the good fortune in Joshimath to meet Pandit Jagdamba Prasad Sati, chief priest of Badrinath for 30 years. He explains that preparations for the closing begin at Vijaya Dasami, the end of the Navaratri festival—October 19 in 2018. It is also at that time the precise date for the closing of the temple is determined. The closing dates for Yamunotri and Gangotri temples are specific auspicious days of the Hindu calendar. Gangotri, for example, closes on Deepavali. For Badrinath, however, the temple closes on a day in November most favorable for the horoscope of the country.

Honoring the Hods and the Ancestors

In the old days, the Tholing monastery in Tibet would make a woolen jacket for the Lord and prepare sufficient yak ghee with special herbs for the shrine’s lamp to burn for six months. When the temple opened again, people from both Tibet and China would come to worship. They are said to have been experts in reading the face of the murti and divining the future of their people. Now these preparations are done by the Bhotia tribe of Mana, the furthermost Indian village of Badrinath valley, who had close relations with the people across the border in Tibet before the Chinese aggression of 1962.

I arrived on November 19, the day before the closing. The temple is decorated beyond recognition with marigolds on every side. The courtyard is packed with pilgrims, all covered with heavy woollens and busy enjoying the beauty of the valley, totally devoid of greenery, as most of it has dried out with the onslaught of winter frost and the first snow, which fell a few days earlier.

There are only a few hotels and ashrams in operation now, and pilgrims have a tough time finding lodging. As evening approaches, the temperature is just four degrees Celsius. Roads wear a deserted look, with all restaurants and shops closed. The only activity is near the temple. Fortunately there are volunteer groups here offering hot food and a wide variety of snacks and sweets.

The severe cold has not dampened the spirit of pilgrims. They stand barefooted in a long queue at the facade of the temple, their numb fingers holding plates of food they will offer inside the house of Lord Vishnu.

The closing ceremony is five days long. The shrine for Ganesha is closed on the first day. On the second, elaborate food offerings are made at the nearby temple of Adi Kedareshwar. On the third, the Vedas are recited and all religious books closed. On the fourth, the chief priest, Ishwar Prasad Namboodri, dressed as a woman, takes the murti of Lakshmi and places it to the left of Lord Vishnu. All the embellishments and jewelry of Lord Vishnu’s murti are removed and packed, and He becomes Nirakar, the Formless God.

On the fifth day, the pilgrims—5,237 by official count—start gathering at the temple before sunrise, many using the sulfur springs for relief from the cold. Puja worship begins at 4:30am. Midway through the morning, Swami Avdheshanand and Baba Ramdev take everyone by surprise with their arrival.

At 1:30pm, Ishwar Prasad Namboodri removes all floral decorations from the murti and dresses it in the woollen coat stitched by the women of Mana. In front of the temple, some of the crowd dance in ecstasy, shouting “Jai Badri Vishal.” Music is provided by a bagpipe band of the Indian Army’s Garhwal Scouts, permanently stationed at Joshimath.

Finally, all eyes focus on the temple entrance. The chief executive officer of the temple, B. D. Singh, escorts Ishwar Prasad Namboodri as he walks backward down the steps holding the statue of Uddhava on his head. This and several other murtis will be sent down to Pandukeshwar and Joshimath for the winter. The ritual is over in just a few minutes, and the temple doors are closed. People bow their heads in gratitude to the Gods for blessing the world with everything.

It’s time to leave. A rush of people, cars, and taxis fill the road. Army vehicles offer to drop people off at Joshimath. Only a handful of sadhus and army people remain in Badrinath for the winter.

Many pilgrims come here every year for the closing. Vinod Paruthi of Dehra Dun has been here 15 years in a row. He gets emotional talking about the closing ceremony. “It overwhelms me, each time I watch it. What a divine sight it is. How can you experience something like this if you remain at home?”Yes, I thought, that is why we pilgrimage: to have the experiences one cannot have at home.

The memories of the pilgrimage stay long in our heads and hearts, undistracted by ups and downs of daily life to which we soon return. What makes us different now? The divine landscape, the darshan of the supreme, in one form or the other, or the echoing of chants like “Jai Baba Kedar” in our ears? Or is it everything that comes our way during the holy travel: the chill of the air, the gurgling noise of those torrents, that shiver down the spine, the vibrance of the sanctum, all so special and lasting. The ancestor worship takes us beyond time and space, to the company of those departed souls. It is like walking hand in hand with the most loved family members who are no more with us now. That special feeling of contentment and accomplishment is something we can’t buy. We are blessed each time we take up something like the holy pilgrimage of Char Dham, our personal meeting with the Gods.

Closing Badrinath for the Winter