Savita Tiwari takes us on her personal pilgrimage to the sacred lake known as Ganga Talao during the island’s exuberant celebration of Siva’s great night

By Savita Tiwari, Mauritius

Savita, 36, grew up in India and is now a resident of Mauritius. She is an avid journalist, blogger, writer and poet with a love of dharma and for exploring many other topics

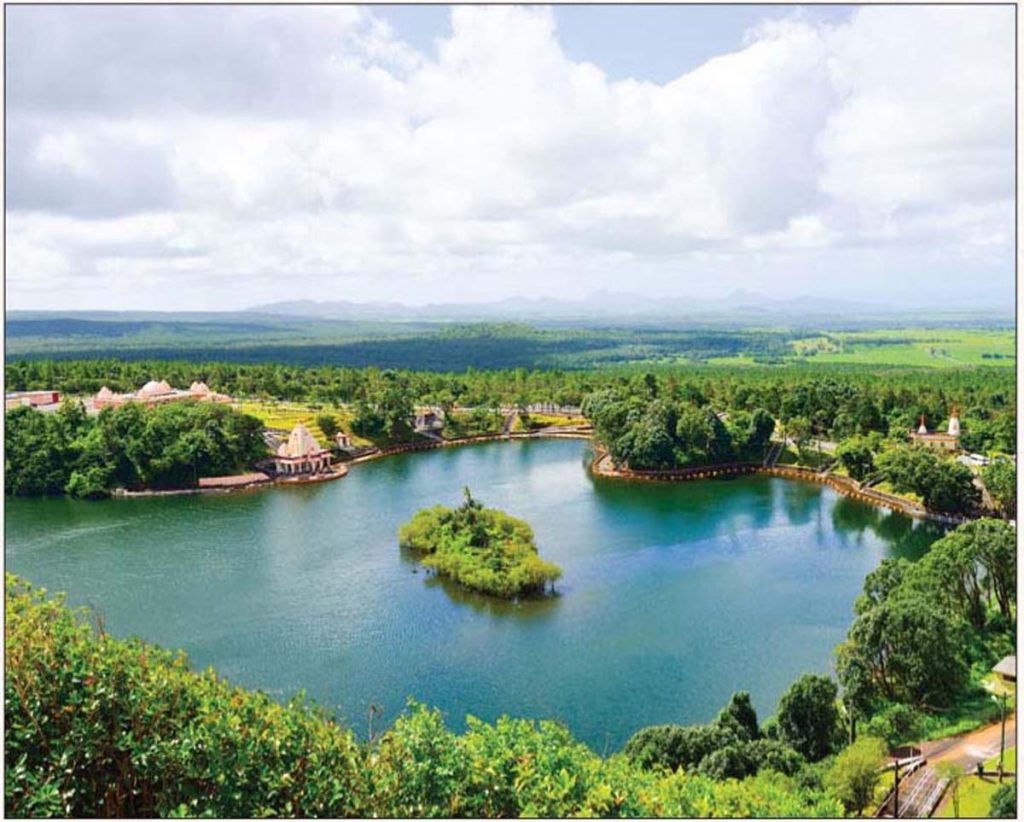

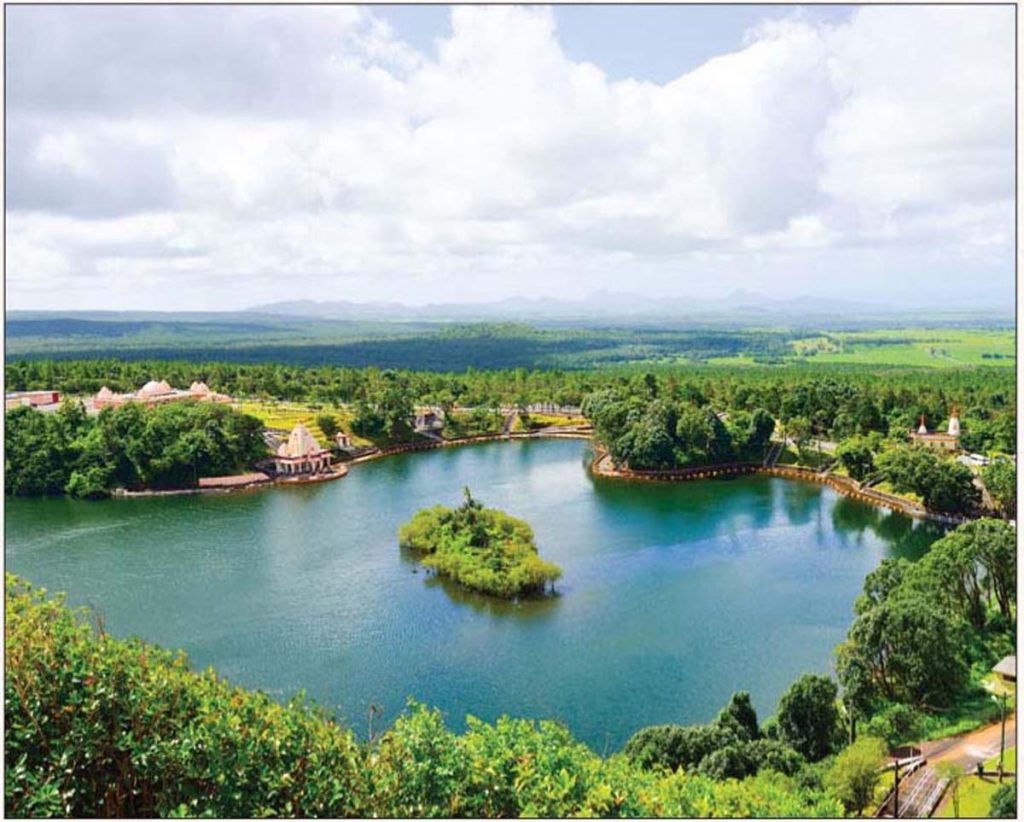

When we think of the great river Ganga, we envision crystalline waters flowing rapidly from snow-capped Himalayan peaks. Few, probably, would imagine a serene hilltop lake. Only on the island of Mauritius, located off the coast of Madagascar, will you find our most sacred river in such an unlikely form—a form known as Ganga Talao.

Mauritius is a small and beautiful island country, situated far south in the Indian Ocean. The island is technically a part of Africa, but the population is more than 60 percent Hindus of Indian heritage. The official language is English, but most Mauritians speak French Creole as their mother tongue, and 14 other languages are also spoken across the island. Truly, Mauritius is a cultural cornucopia, a world within itself with African, European and Asian footprints. You’ll see mainly Western outfits as people walk through the streets; but pass by a Hindu temple or community event and you’ll likely see an assortment of colorful sarees, chudidaars and kurtas. There is plenty of Indian food to be found, even though the island’s renowned French cuisine often takes center stage. The island is quite small, at just 48 miles from Gris Gris in the south to Grand Baie in the north, just a one-and-a-half-hour drive. The distance from east to west is 34 miles.

The three thousand miles of ocean between India and Mauritius have not weakened the spiritual and religious connection. In the lives and upliftment of Mauritian Hindus, few places hold such importance as Ganga Talao—for it fulfills the same role on our island as Ma Ganga plays throughout India. As Mauritians, we may not have the idyllic, milky-white river to turn to for reverence, but on Mahasivaratri, “Siva’s great night,” countless pilgrims from all over the island make the yatra (pilgrimage) and padyatra (pilgrimage by foot) to Ganga Talao, experiencing the same holy effect on mind, body and soul. On their shoulders, many pilgrims carry kawar—decorative structures, large or small, used to transport water from the lake. Thus these pilgrims are known as kawartis, andtheir trek is known as the Kawar Yatra. The goal for many is to travel from their local temple to Ganga Talao. Once there, they gather the lake’s sacred water and carry it back to their home temple as an offering.

The feeling of Mahasivratri in Mauritius buzzes in the air and in the attitudes of everyone you meet. Men, women and children, most dressed in the white garb of pilgrims, are found walking en masse along the roads towards the lake. Streams of kawartis are accompanied by other foot travelers, while some pilgrims opt to travel by car or bus. Everywhere the white clothes of traveling pilgrims dominate the nation.

Rest houses, temple halls and individual homes all over the island are decorated with flowers, leaves and pictures of Lord Siva, indicating that these places are available for travelers to rest and sleep, or for kawartis to take a break from carrying their cargo. Gifts and supplies are stockpiled at important junctions, welcoming the kawartis and providing sustenance along their journey. Local companies distribute white t-shirts to pilgrims enroute to Ganga Talao, and many people and organizations hand out juices and snacks. Pilgrims are lavished with free sweet-potato cakes with coconut, fried and battered chili peppers, rice pudding, fried breads, fried chickpea-battered potatoes and many other mouth-watering edibles.

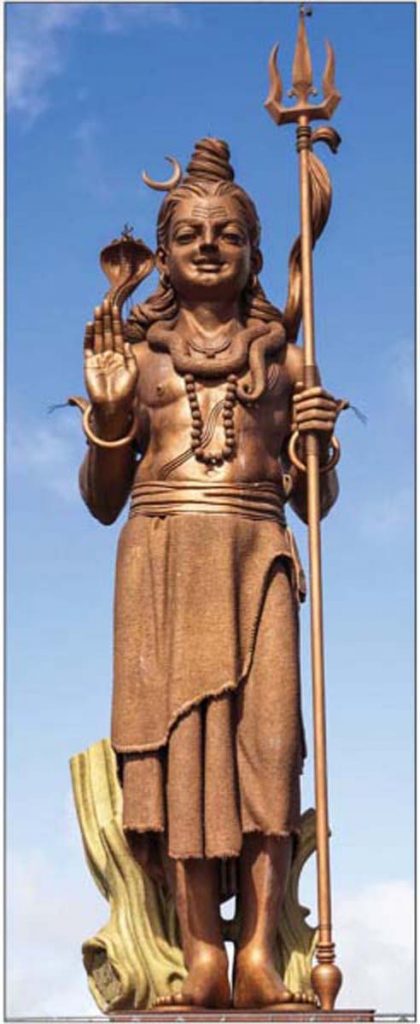

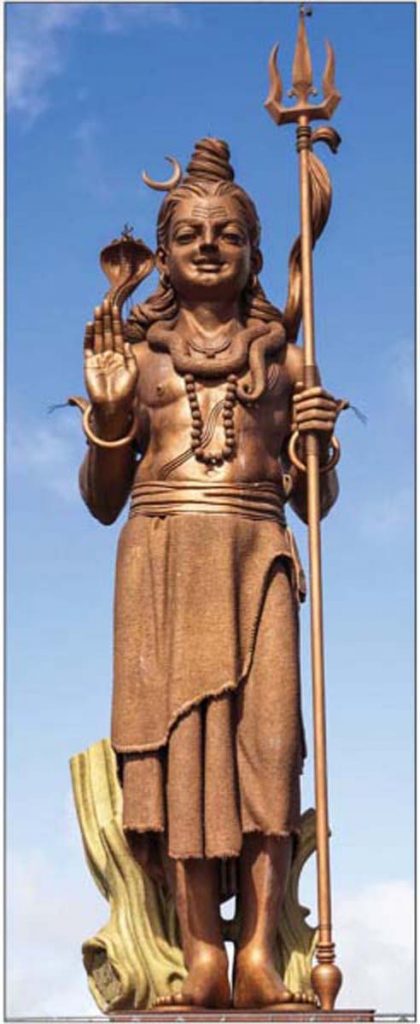

As you leave the festive towns and make your way up through the forested hills, you come closer and closer to Ganga Talao. On arrival at the lake you are welcomed into a different world by Lord Siva Himself. Standing 108 feet tall, He is the largest figure on our island. Calm and smiling, He looks out over the sacred lake with the same peace that approaching pilgrims feel in their hearts. As you walk past Siva’s feet, you are enveloped by the sound of bhajans, bells and voices chanting “Hara Hara Mahadev.” This may seem like the end of the pilgrimage, but actually your spiritual journey is only just beginning.

Preparing for Pilgrimage

In planning to write this article for Hinduism Today, I want to find a perfect way to cover these festivities. I am not sure where to start—until Mahadev Himself resolves the issue, when a friend invites me to start the Kawar Yatra from their temple in Grand Baie. As the northernmost location of our island, this idyllic bay is the furthest point from which you can begin the yatra to Ganga Talao in the south. This would be perfect. Because of the distance, pilgrims starting at Grand Baie are the first people on the island to begin the yatra. They start three to five days before Mahasivratri and travel some 75 miles to and from the lake.

A two-hour taxi ride brings me to Grand Baie at 6 pm on the day the yatra will begin. The ride presents me with the first of many interesting meetings and happenings that will define my journey. My cab driver’s name is Ketan—Ken to his friends—and he seems to have views on almost every topic in the world. Instead of the common pleasantries of “namaste,” he asks me, “Why are you going so far, all the way to Grand Baie, to write your article? You will end up passing 100 temples on the way, each playing the same scene: people gathering and bidding farewell to all the kawar carriers as they leave for Ganga Talao. What’s so special about Grand Baie? It’s a tourist destination without many locals and without many Hindus.” His words are a little discouraging for me, but I think, “Let’s just reach Grand Baie first and find out for ourselves.” All the way he is criticizing Hindus on the island for not taking care of their religion, complaining that bygone days were much better.

As we reach the Siva Kalyan Nath Temple in Grand Baie, my driver falls silent. There in front of the temple is a crowd 500 strong—pilgrims dressed in white and ready for the departure. With them stand their families and friends, wishing them well. I glance at Ketan with smile. He quickly responds, “So what? It’s not a big deal. They all are Hindu. By coming to temple today they are not doing anything out of the ordinary, it’s just obligatory.” It’s hard to make some people see good in things, I guess.

Inside the temple everybody is greeting each other with “Har Har Mahadev.” I do not immediately find the friend who invited me, but I soon meet Sudhir Gungadoss, who is serving juice to the kawartis and instructing them to take care of themselves: “Drink enough fluids on the way, it’s extra hot these days. Walk in the morning, evening and nighttime hours and avoid walking in the afternoon. Take afternoon naps at rest areas. Keep your raincoats! Just because no rain has been forecast for the next few days doesn’t mean it couldn’t still happen!” Nobody pays much attention, though. Many have heard these words all their life. Sudhir offers me juice, and I take the opportunity to ask him questions. He tells me he is responsible for the cooking department of the temple, and explains their schedule for the festival: “There are two temples in this area, and around 500 to 600 people go on foot to Ganga Talao from Grand Baie each year. Normally the Kawar Yatra starts just a few days before Mahasivaratri, but the yatra beginning from this temple follows a different routine.

It is a long journey, and we have to take care of the kawartis’ health, so we take it slow. We start our journey three days before, and we have special places where we rest. We travel only in the morning, the evening and at night. It’s important we follow these guidelines, because we have to travel around 37 miles to Ganga Talao and then back the same distance.”

I ask him about the kawar that are carried. He says, “Because of the long distance, many large kawar are made with wheels. It is actually more like a parade float, but since the kawartis use them to carry the water they collect from Ganga Talao we still call it a kawar. We reach Ganga Talao in the afternoon on the day of the official festival there, and we visit the lakeside temples. We gather water from the pure lake and then take an afternoon nap so we can start back the same evening.

“We return to our temple carrying the sacred water and usually arrive on the third night or early the fourth morning, which is Mahasivaratri day. We keep the kawar in the temple and sleep there ourselves before participating in Brahma Muhurta puja on the day of Sivaratri. Everyone then goes home to bathe before returning to the temple to have prasad as breakfast, lunch and dinner. The whole day is spent at worship in the temple. Then all the kawartis participate in char pahar puja, which includes pouring the collected water over the Deity. This starts around 6pm on Mahasivaratri evening and ends at 5am the next morning. Everyone participates in the final havana. Then we take prasad and return to our homes energized with Siva’s blessings for the entire year and with the determination to re-enliven our lives again next year with another five days of worship.”

As I finish chatting with Sudhir, I notice a girl taking a selfie next to a kawar. I ask her if she is going on foot with the kawar and she says yes. She tells me she is 18 and this will be her second year walking the yatra. Last year she was so tired on the return journey that she took a bus part of the way; this year she is determined to complete it all on foot.

She says, “On the return trip everyone is very tired. During the whole journey, you take baths in the public bathrooms, sit on roads and sleep in tents. As you can imagine, we don’t bother to take selfies with the beautiful kawars at that point because we look and feel exhausted.” I ask her why she does it all if it is such a challenge, and, just like that, this 18-year-old selfie-girl turns philosophical: “These five days out of our comfortable homes may be five days of physical pain, but they are also five days of relief for our souls. We feel so proud of ourselves. Our parents feel proud as well. Last year my parents praised me in front of every guest coming to our home, telling them I had walked the padyatra to Ganga Talao. Although, I felt a little guilty when they would edit out the part where I took a bus.

“Overall, doing this yatra makes you feel fulfilled and happy for the whole year. And besides, living on your own for five days is an experience every youth wants to have. Also, kawartis coming from Grand Baie get a lot of respect because we travel farther than anyone else on the island.”

The Yatra Begins

A bell starts ringing in the background, and Selfie-girl perks up: “Ok, I have to go. It’s puja time. This is another thing we all love about the event. All the aratis done for the departing kawars are done only by women. It’s fun. It kind of feels like we are soldiers going off to some great battle as the sky is filled with the sound of ‘Har Har Mahadev.’ It really gets the adrenaline going!”

As Selfie-girl rushes off to help with the aratis, many of the mothers of the kawartis are ready with puja plates to bid their children farewell. All the kawartis stand in a line, and the temple acharya comes through to give a blessing for each kawar by breaking a coconut. Suddenly, just like Selfie-girl had said, the sky is filled with “Har Har Mahadev! Har Har Mahadev!” and 500 people with hundreds of kawars begin their march to Ganga Talao. I have never witnessed anything like this before.

I don’t walk the yatra with this group; instead, in order to stay fresh for my interviews, I utilize taxis to meet people along the way. The next day I catch up with this same group at a rest house area in Beau Bassin at eleven o’clock in the morning. Everyone is fast asleep. Only a young couple are awake, chatting quietly. I want to interview someone there but don’t want to disturb these two, so I wait outside for another pilgrim to wake. Just then an elderly man walks up, intent on resting here.

“Bonjour madame, why are you sitting outside?” I tell him I want to speak with the young couple inside but don’t want to disturb them. He looks inside, then returns with a broad smile and sits beside me. “Today’s youth are more devout than my generation was. I used to do this yatra when I was young. But the fact was, I started the padyatra for Ganga Talao just so I could meet up with my girlfriend. Those days parents were very strict. Padyatra was a good option for dating,” he laughed. “But now youth can meet whenever and wherever they want, yet they are still trekking to Ganga Talao. So I feel like they are more religious.”

I inquire about those early days. “Twenty years ago this yatra was more of a thing for elders, and not many youth participated. But today youth make up the majority. In those days we would just string two water pots to a bamboo stick and our kawar was ready. But now we see youth working for a whole month every night after their jobs or school studies. They gather in their village temple or any other place that will do and they prepare their kawar. It’s so nice to see them working hard for their religion.”

I leave the Grand Baie group sleeping peacefully and head to La Marie, the last village on the way to Ganga Talao. After La Marie, it’s just lush green jungle and forests, but with unexpectedly well-paved roads—made so specifically for this event’s massive yearly traffic. It is a vast and peaceful nature reserve. Like other towns along the pilgrimage routes this time of year, La Marie is experiencing a large traffic jam of people headed to the lake. I get out of the taxi and proceed on foot. This is the best way to explore anyway. Most of the year the motor traffic makes it unsafe to walk along the roads, but during Mahasivaratri, with thousands on the roads, it’s quite safe.

I spot an Indian couple having juice at a nearby tent. Mauritians have nearly the same features as Indians, but identification is easy because the two groups carry themselves differently. I join them and indulge my love for conversation. Mamta and Rajesh are their names. Rajesh has joined a telecom company in Mauritius, and they moved to the island just six months ago. This is their first Mauritius Mahasivaratri. I ask if they are enjoying the week of festivities. Mamta exclaims, “One week? More like one month!” They both start laughing. “You know what happened to us a month ago? As you know, after 8pm you barely hear a sound in Mauritius. But at 9:00 one evening we suddenly heard a noise like someone was trying to break into the house. Rajesh grabbed a badminton racket and I rushed to the kitchen to get a knife. We were so scared. When we reached the back door, we realized the noise was coming from the back yard of the temple next to our house. Thinking thieves had come to steal from the donation box, we immediately called a member of the temple committee. We felt so proud to be saving the donation box.

The committee member rushed to the temple—and five minutes later we were being laughed at from over the temple wall. The committee member and about ten young boys were there. The boys had been planning and building their kawar for Mahasivaratri. Standing there with badminton racket and knife in hand, we could only laugh at ourselves. It was so embarrassing. So you see, we learned the hard way that, here, Mahasivaratri starts a month in advance!”

This brings a big smile to my face. It is wonderful to find yet another mention of our youth’s dedication to their religion. I’m told all pilgrims observe a strict vegetarian diet for the month that they are building the kawars. During Mahasivaratri Week, all Hindus on the island are strict vegetarians, even those who eat meat at other times.

Providing for Devotees

On that note, it’s hard to discuss Mauritius Mahasivaratri without mentioning food. With all the free food distribution, you can feel the presence of Annapurna, the Goddess of nourishment, who has come to feed the pilgrims. All over the island Her presence is manifest in all who help provide for the devotees who have left their houses and villages to pray to Lord Siva.

Nobody has ever claimed to know just how much free food is actually distributed around the island during this week, but it is an enormous amount. The Human Service Trust (HST) alone feeds around 150 thousand people over three days at Ganga Talao—and HST is just one of several hundred organizations that provide free food all over the island. Along with community organizations, many temples also provide rest and food facilities to kawartis, along with bathing facilities. These facilities are mainly for kawartis traveling on foot, but even people driving by car are welcome to have food from them.

Many individuals also turn their homes into rest houses. A Mrs. Kisson from L’Avenir tells me she and her family wait with anticipation each year for Mahasivaratri, just so they can serve people going to Ganga Talao. “It’s the most beautiful part of Mahasivaratri. All year we are just four people in this big house, but on Mahasivaratri it’s like having a festival in our home. We have done this for the last ten years, and now we have some kawartis who never miss paying us a visit.” Other individuals cook fried vegetables, dals, puddings and cakes at home and take them in vans to distribute to people held up in traffic jams. They’ll also serve this food outside temples where weary and hungry wayfarers are waiting in long lines for darshan. One smile and a “thank you” from the receiver is sufficient repayment for the giver.

An English Pilgrim

At one such stop I hear someone behind me saying, “Anna data sukhi bhave,” after receiving rice pudding. I turn around to see an Englishman in his sixties wearing a white dhoti, kurta, a tulsi mala around his neck, a beautifully painted tikka and a friendly smile on his face. I smile back and ask what his words meant. Though I know they are a blessing honoring the source and giver of the food, I feel that from his answer I might still learn something. The old man beckons me to sit at a bench nearby. He is in the mood to offer a whole lecture, and I am always up for listening—especially when I have an article to write.

He tells me he feels like “a tourist on Earth who wants to thank everyone who feeds him along his journey.” Now that is more philosophical than I expected. I ask him what bought him to this part of Mauritius. He says, “I am not here just to go to temples at Ganga Talao and get Siva’s darshan. If I wanted that, I would have gone to some Jyotirlinga in India, which are very powerful and beautiful. But the beauty of Mahasivaratri in Mauritius lies outside the temples, and this is the main reason I come here on Mahasivaratri every year. The ambience is so beautiful. You can feel the meaning of ‘Sivaoham’ in this spiritual atmosphere.

“You know, Mauritians are very strict about their jobs and day-to-day routines. They even make sure their marriages are on Saturdays or Sundays so their everyday life and work will not be disturbed. But they break all their rules for God Siva. They don’t mind kids skipping school during Mahasivaratri; they save up their sick days from work, just for this time of year; and though they never walk on roads all year, on Mahasivaratri half of Mauritius is walking through the streets. Here you can see Siva’s presence in all the free services and all the giving. At this time of year you don’t have to enter temples to feel Lord Siva’s grace—you can feel Him everywhere.”

Discovering Ganga Talao

I leave La Marie and make my way up through the nature reserve to Ganga Talao, arriving along with countless other pilgrims. As you enter Ganga Talao, you cannot miss the 108-foot-tall statue of Lord Siva greeting you; but just a little further my attention is drawn to a small, less obvious statue, an ordinary-looking man holding a kawar on his shoulder. Why is this statue standing here with images of the Gods? I learn this is a statue of Jhummun Giri Gosai, the first person to set foot on the Kawar Yatra to Ganga Talao. He is the man behind this world-famous Mahasivaratri celebration.

In 1898 Jhummun Giri Gosai, a Siva bhaktar and a resident of Triolet in northern Mauritius, had a dream. In that dream a group of fairies led him to a sacred lake on a mountain in the south of the island. There they told him that he no longer had to miss the sacred waters of Ma Ganga in India. He had no idea then that his dream would shape the spiritual destiny of the whole island.

Days later he decided to search for this place with a friend. To their amazement his dream was true—he found the very lake which the fairies had shown him. Overwhelmed by the experience, he promised himself to walk to that lake every year on Mahasivaratri. He also installed a Sivalingam there, and the lake became known as Pari Talao, “Lake where fairies reside.” In 1972 water was brought from Gangotri, India, and poured into the lake, and it became known as Ganga Talao.

Having now heard a great deal of testimony from pilgrims, I want to speak with someone in government and get their thoughts. During the festival, all government officials, including the prime minister, visit Ganga Talao. I meet Mr. Somdutt Dulthmun, president of Mauritius Sanatan Dharm Temple’s Federation, in his organization’s tent. I ask him how he views Mahasivaratri in Mauritius today. He tells me, “In today’s world, where every religion is facing the problem of their youth becoming disinterested, it brings me peace to see that the Kawar Yatra of Mauritius represents the power of the youth in our country. I feel immensely proud to say that 90 percent of kawar coming to Ganga Talao are on the shoulders of our youth. Thousands of kawar reach Ganga Talao every year on Mahasivaratri—so many that we’ve had to start asking pilgrims to just bring small kawars on their shoulders as foot traffic, because the larger ones are causing extra congestion along the roads. Travelers are sometimes stuck in traffic for 5 to 6 hours at a time. Thankfully, many groups are heeding our requests. Some have begun making and bringing small, beautifully made, identical kawars. All these kawartis will wear uniform clothes for their march to Ganga Talao. It looks beautiful and it is also more traditional, bringing with it a sense of personal bhakti that might not be as present when simply walking alongside a float. Overall, Hinduism in Mauritius is in very good health.”

I make my way from the organization booths down to the lakeside. At the lake, everyone is feeling Siva’s presence, including me. Vedic chants echo through the air as priests perform pujas. Incense billows from the temple entries and from the many lakeside offerings presented by pilgrims. Youth gather water from the lake for their kawars, which are lined up above the lake, colorfully decorated and waiting to return to their temples.

After this, I will leave to celebrate my own Sivaratri. Without a doubt, this has been one of the most memorable Mahasivaratri celebrations I’ve ever experienced, and I’m excited to see what next year will bring. Aum Namah Sivaya.