By ARCHANA DONGRE, Los ANGELES, AND RAJIV MALIK, NEW DELHI

Pre dawn, early February, 1995, a team of 18 Indian photographers departed Delhi and Mumbai with 50 rolls of film each to reach the remote corners and isolated corridors of India. Hand picked for their world-class artistry, they crisscrossed the subcontinent to capture the people and poignancy of locations that had been scouted and researched for three months. Four days later, 35,000 photographs were submitted. In addition, video and film crews numbering 200 followed the photographers in an attempt to preserve the fleeting moments in moving pictures. This impressive effort spawned a beautiful book and a fantastic documentary film, both with Eastern and Western editions.

Michael Tobias, a Los Angeles-based, 40-something author, film actor, ecologist and historian, was the prime motivator in the photographic effort. He also wrote the text, and produced and directed the video. He worked hand in hand with Raghu Rai, distinguished Indian photographer, to choose the team members and help them determine their themes. Tobias recounts, “My specific instruction to each photographer was to hold utmost respect for the subject and environment they are shooting–for the quiet dignity of every jiva involved–and not to modify anything, to capture unobtrusively the ordinary.” Together, Tobias and Rai had the arduous task of selecting 200 photos from 35,000–culling the best from the best.

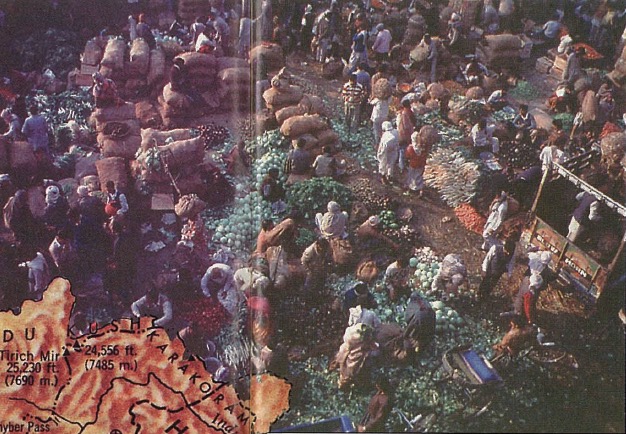

The result of the year-long editing process was the large book, India 24 Hours, published in India by Mapin/Grantha in 1995. In 1996, Harper Collins bought the rights to publish it in the US. Collins’ edition is the just released, A Day in the Life of India, the newest in the prestigious Day in the Life photojournalistic series by Harper Collins Publishers, San Francisco. The book is a pictographic, photo-journalistic attempt to convey the ripples, rhythms, ebbs and flows of everyday life in Bharat. One hundred eloquent, timeless images (a few are reproduced here and on the cover) capture the sublimity in the mundane–from the most ancient village traditions to the maddening pulsations of her modern cities. The Collins edition is stunning at 14 x 10 inches, but the Indian edition has more photographs and about 80 more pages of Tobias’ text.

Both Tobias and Rai seem to prefer the Indian edition, as Rai described, “The final editing by the publisher [Collins] diluted the effect I wanted to produce throughout the book. The publisher added pictures other than those I had selected. Certain pictures I wanted used large were used small, so their impact is not as great. Editing is like magic. If you put two good pictures side by side, they can enhance each other. On the other hand, if you put two wrong pictures together, they can kill each other.”

The cinematographic effort first manifested in a two-hour Indian edition, India 24 Hours, that aired on Doordarshan TV, January 26, 1996, with warm reviews. A 56-minute US version, also titled A Day in the Life of India, [see sidebar, pg. 24] is scheduled to air in the US sometime in 1997. The film details some of the making of the book as the photographers explain their artistry on location.

The dream team: These are influential works, to be sure, but Rai deems the production itself to be more significant than the product. “For me, the biggest fulfillment was that a team of Indian photographers collectively participated to make this project a success,” Rai assessed. “The greatest problem we have in Hindustan is that each one keeps to himself. We do not pool our resources. We are not working together. Today, this is the spirit of Bharat. Whenever a project like this comes, we appear to the West as if we are a lifeless people. But here, the achievement was our collective participation and work as a team.”

Though at the core of the project, Tobias was reluctant to highlight his own participation. Instead, he said, “Some of the key people were Kirit Mehta, who is something like the Ted Turner of India, and Parul Shah. They are driven, dedicated and brilliant.” He also detailed a few of the obstacles the team had to overcome, “Coordinating the project was very difficult in view of the fact that there are no cellular phones. You cannot reach people on the road, so scheduling and logistics were awkward. Locations like Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh posed difficulties due to extreme cold and the remote, mountainous region. Photographers got frustrated and fell ill in these far-out locations. But despite all this, the project went without a hitch.”

This helps to explain why it actually took 100 hours to photograph a mere 24 hours worth of India. Rai attests that even 100 hours is too little time, “I would have asked for ten days and assigned the job to fifty photographers. India is a wondrous nation. To truly capture it can take a few centuries, let alone a few days.” Tobias concurred, offering, “India is too complex, too vast–with the modern and the most ancient coexisting side by side. This country has the greatest diversity in the world. How can you do it justice in just 24 hours?”

Why then call it “A Day in the Life?” Rai explains the concept, “Even A Day in the Life of America was not done in 24 hours. What it means is that you have to portray how a day in the nation begins and how it comes to an end.” And this is the unique and intriguing feature of the book. The opening pages portray sunrise and early morning. Paging through the scenes takes you progressively through India’s noontime, afternoon, sunset and evening. The film follows the same pattern.

Bharat in the balance: As the reader pores through the book’s beautiful photographs, accompanied by adequate captions indicating thorough research, one notices a strong bias toward the rural and tribal faces. Village scenes and the environs of the indigenous people, the Adivasis, peer out from numerous pages. Despite a few shots of skyscrapers, a modern mother and child or a model beside a car here and there, the middle class is conspicuously absent. Western photographers and journalists are often accused of focusing their lenses on either stark poverty or palatial grandeur. In this project, where the photographers were all Indian, why do we not see their sensitivities and sensibilities capturing the images of India’s middle class?

Hinduism Today asked Tobias and Rai, but neither one felt that India was slighted in the photo-editing process. “There are 150 million middle-class people in India, versus 710 million in rural areas,” Tobias explained. “We were looking for uncliché, timeless images, like a living time capsule. We could not cover every corner. The book reveals the way people live, unencumbered by any definition. It is not a scholarly thesis, but a mirror of the way things are. We had to use subjective, artistic, poetic criteria.”

Rai was more specific, “The only parameter for the selection of the photographer was that his work should have freshness and intrinsic strength. They were given suggestions, but we allowed them the freedom to select their assignment. We told them to shoot whatever touched their imagination, or which they thought was important. In this way, you can expect the best out of that person. In choosing the photographs the only criterion was merit. It was not based on any religion, but simply the results of intuitive, creative people and what they found to be powerful moments.”

Also manifest in both book and film is an absence of images of Hindu temples and ritual worship. The devout Hindu will no doubt notice this. But Rai himself contends, “It is wrong to say that Hinduism has not been properly represented.” While Tobias countered our challenge, “Hinduism is inherent in numerous images. There are Sadhus from the Kumbhamela, glimpses of Varanasi and the banks of Ganga, people in a Mathura temple, and a window from the Swaminarayan Temple in Bhuj, western Gujarat.”

Bharat darshan: In the end, Raghu Rai offers a deeper perspective on the merit of these weighty works, bringing to the fore the ultimate and timeless value of a book that delivers India to your front door. For Rai, A Day in the Life presents the darshan, sacred sight, of India. “The philosophy of darshan is very meaningful in photography. Darshan takes place when one becomes transparent, merges his mind in the situation and truly sees the world. I have learned this from the camera itself, but it can happen with the naked eye as well. There are open and simple people whom you can see inside and out. With such people, my soul communicates. That is the true darshan of somebody. In Hinduism, we even say, ‘I had the darshan of God today,’ and I do meet people in whom I see God. In our dharma, if you have darshan of life and nature, you view the Almighty. He is in each one of us.”

Harper Collins Publishers, 1160 Battery Street, San Francisco, California 94111 USA. Tel: 415-477-4400; Fax: 415-477-4444; www: http://www.harpercollins.com; e-mail: harpercollins.com

SIDEBAR: A “LOVE LETTER TO INDIA”

Producer Michael Tobias presents Bharat to the world

India holds a magical charm for Michael Tobias, who has penned 21 books and has written, directed and produced more than 100 films in 50 plus countries of the world. About A Day in the Life of India, he admitted, “It is my personal love letter to the country–the friendliest country in the world.” He uses expressions like “inexpressibly lyrical” and “abundantly poetic” when talking of India. He has made some 25 trips there, first as a teenager. He has close Indian friendships, follows Jainism and is an advocate of ahimsa, non-violence.

Although the present production was difficult, at best, Tobias unreservedly declared, “l have made over a 100 films around the world, but despite its problems, this was by far the most wonderful, most joyous I have experienced.”

When asked exactly what the challenges were, Tobias quickly recalled, “Our cameramen got sick and frost-bitten. Dealing with Indian accents for international audiences posed stubborn difficulties. In Arunachal Pradesh two groups started fighting because it was a custom in the wedding that was being filmed. But our photographer got scared. He thought they were fighting with him. Also, the people put heaps of dead rats in his jeep because they were transporting those for sale.” This is one photo we will not miss.

Tobias’ own background as a scholar of anthropology explains his intimate portrayal of Adivasis and rural communities. Especially in the film, you see close-ups of the individuals and lifestyles of the Gonds and Bhils of Madhya Pradesh; the Todas of South India; the rural communities of Coorg; Thar desert, Rajasthan; Arunachal Pradesh and the fishing communities of Kerala’s backwaters.

Tobias’ future holds a speculative endeavor, “I would like to do a book about every state in India. The country has been a photographer’s dream ever since photography was developed.” If anyone can do it, surely it is he.