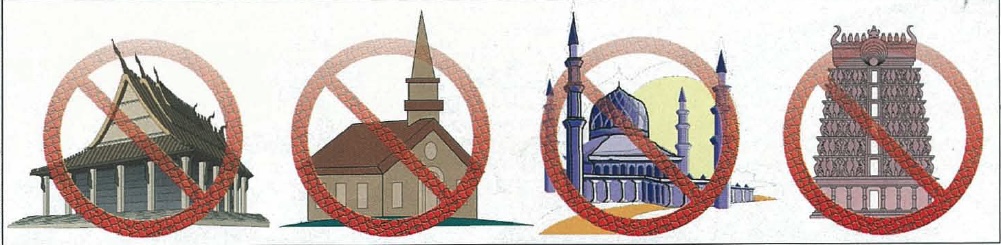

Trustees of Hindu temples in America learn quickly that for all the talk about religious freedom as a foundation of the country, few people welcome a Hindu temple in their community. It’s nothing personal against Hinduism, really, for every other religious group gets the same treatment these days. “Not in my back yard,” say the neighbors, followed by the stock litany of objections: “Too much traffic, too much noise, no parking space…” and an appeal to the local county planning commission to rule that the temple, church, mosque or synagogue does not meet local zoning requirements. One shouldn’t really blame the neighbors for their opposition, especially the ones right next door, if the temple is in a residential area. It is a known fact of real estate that a house next to a new church or religious building will lose property value.

County zoning ordinances were getting so good at excluding religious buildings that it was becoming difficult to get anything built in any community. Hindus, Buddhists and Muslims responded by buying old Christian churches, then claiming “established use,” purchasing large empty lots in the middle of sparsely populated areas or even moving into industrial parks where neighboring businesses were not only unconcerned about additional activity, but often lent their parking lots for weekend services.

A Jewish congregation in Los Angeles just wanted a permit to meet in a local home on their Sabbath day. The Los Angeles City Council refused. In Chicago, His Word Ministries to All Nations encountered delays and rezoning tactics that not only prevented them from building in the area they wanted, but wasted a year of their time and considerable money in the process.

The Christians finally got fed up with the obstructionist tactics they were encountering across the nation and approached the US Congress for relief. Congress responded with the Religious Liberty Protection Act, which was so broad that the Supreme Court prompted struck it down as unconstitutional. Congress tried again and passed the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act, and President Clinton signed it into law September 22, 2000. The law is abbreviated RLUIPA (pronounced, someone decided, “ar-LOOP-uh”).

In the past, the local government only had to prove that the land use regulation they were trying to impose applies equally to all institutions in the area, regardless of whether religion was involved or not. Now, under RLUIPA, the government has to show that the restriction is “in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest and is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest”a much, much more difficult test. The law states that, with regard to land use, the local government cannot treat a religious institution on less than equal terms with a nonreligious institution. Finally, it states, “No government shall impose or implement a land use regulation that totally excludes religious assemblies from a jurisdiction or unreasonably limits religious assemblies, institutions or structures within a jurisdiction.”

The second part of RLUIPA affords considerable rights of religious observance to persons in prison. A jailed Hindu might, for example, be able to insist on vegetarian meals. Muslims have successfully used the law to avoid being served pork.

But it was the first section of the law that left local governments aghast. “In no uncertain terms,” announced Juan Otero of the National League of Cities, “the law is a direct blow to local governments across the nation and represents efforts to federalize local zoning. Under RLUIPA, local ordinances will be challenged, allowing religious organizations to evade such things as parking restrictions, setback requirements, tree ordinances, drainage requirements and noise limits. According to the law, religious institutions can be large facilities with activities beyond worship services.”

Churches began to use the law immediately. A congregation in Michigan challenged a city hall ruling preventing them from opening a storefront church. A large Mormon temple was built in Belmont, Massachusetts, despite local opposition, because of the law’s protection. Churches that operate homeless shelters or rescue missions made effective use of the law to prevent closure of these activities.

An article in Liberty magazine, put out by the Seventh Day Adventists, summarizes the RLUIPA’s impact. “The next time a zoning board gives a church the runaround when it is simply trying to buy a piece of property or get a variance to use property for religious purposes, the church can do more than simply beg and plead. Now it has a way to force the government to the bargaining table, and then to court if necessary. RLUIPA’s passage means that if neighborhoods permit home book clubs, they should not stand in the way of home Bible studies. It means that cities can’t suddenly decide that increased traffic justifies barring churches from meeting in rented storefronts, schools and theaters when those same places generate plenty of traffic for secular purposes.”

Hindu institutions should consult their lawyers and study the rights given them under RLUIPA. Certainly it would have helped in many past situations with temples in a number of cities, and may now make founding a Hindu temple a much more pleasant and unhassled religious duty.