BY HARI BANSH JHA

Just one day before i departed on pilgrimage to Muktinath, a pious friend of mine dropped by my home in Kathmandu for a casual visit. When he came to know of my impending expedition, he lit up like a light. Suddenly, he couldn’t stop talking. “According to legend, ” he exclaimed, “the sins of a man planning any serious pilgrimage to a holy place become clutched with fear and run for high ground to hide in his hair. This is why so many pilgrims shave their heads before going on pilgrimage.”

Even as my rational mind was picking over this allegorical statement for philosophical loopholes, my friend was continuing his inspired proclamation. “To further guarantee the eradication of their sins, ” he said, “these serious pilgrims practice disciplines like chanting the Lord’s name, meditating on His presence, associating with holy people along the way, practicing charity and walking rather than riding, as much as possible. Is this your plan? Will you be doing all these things?”

“I certainly intend for this to be my finest pilgrimage ever, ” I stammered, feeling almost defensive. At the very least, I was now in a proper mood for Muktinath and all of the spiritual adventures it might have in store for me.

Muktinath is to Hindus and Tibetan Buddhists what Mecca is to Muslims and Jerusalem is to Christians. Mukti means “liberation, ” and nath means “Lord.” Thus, Muktinath literally means “the Lord of Liberation.” Several Hindu scriptures mention Muktinath, especially the Ramayana, Mahabharata and Puranas. A pilgrim approaching the 96 square miles of Muktinath, also referred to as Mukti Kshetra and Shaligram Kshetra by pilgrims, feels a palpable divinity that invites an ultimate merging with God.

I set out for Muktinath on October 30, 2004, traveling the first part of the journey by plane to avoid the frequent roadblocks set up as a result of Nepal’s on-going insurgency. On the flight coming into Jomsom, a small township which is some 25 or 30 mountainous miles from Muktinath, the aircraft I was on flew so dangerously close to the jagged mountain ranges that, at least on one occasion, I instinctively clutched the arm rests of my chair, dead sure that if this wasn’t my finest pilgrimage, it would certainly be my last. Following a remarkably graceful landing at about 7:30 in the morning, I most happily prepared to take up the last portion of my journey on foot.

By 8 o’clock, I was walking with vigorous determination toward Muktinath. I met a number of wonderful foreigners along the way. Because tourist season in this part of the world lasts from the beginning of October to the end of November, there were not many locals on the trails at this time, as they avoid outsiders.

By noon I had been on the move for nearly five hours and was growing quite tired. The journey thus far had been mostly up-hill and the heat was becoming oppressive. I had been pushing myself like a soldier, and this willful approach was beginning to wear a little thin. Ripe for a change of perspective, I suddenly remembered something Ramana Maharishi once said. “In approaching a temple or a holy place, ” he had explained, “one should walk slowly, like a pregnant woman.” This made a lot of sense to me right at that time. Suddenly, I found myself chanting the Lord’s name and thoroughly enjoying an unhurried ramble toward a destination which was beginning to feel more like it was within, rather than ahead.

As I was about to reach the Muktinath temple, I recalled something else I had been told by a bare-footed, half-naked, dread-locked Indian ascetic I had met at this same place some ten years ago when fate had thrown the two of us together on a pilgrimage. At one point, he turned to me and said, “Coming from a foreign land, even a King must face certain hardships.” Truly, God’s wisdom shines everywhere.

In addition to the image of Lord Muktinath, devotees coming to the Muktinath temple worship a simple black, glossy stone known as a Shaligram. Representing Lord Vishnu to the Hindus and Buddha to the Buddhists, this Shaligram, which bears a 400-million-year-old life history and can only be found in the Krishna Gandaki river, was named after a holy man known as Shalankayan Rishi who attained enlightenment under a tree in Muktinath during Vedic times. Today in honor of this legend, the 96 square miles surrounding Muktinath is referred to as Shaligram Kshetra.

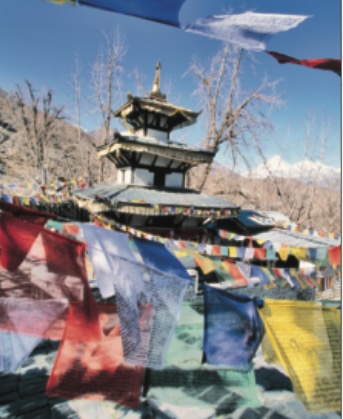

Nothing can express the joy I felt when my eyes first fell upon the beautiful pagoda-style temple of Muktinath just before sunset. I was 13,000 feet above sea level, and felt like I was in some other world. I even forgot that I was tired. “How long have people been coming here to worship?” I mentally asked myself. No one knows.

A Queen named Subarn Prabha reconstructed the temple that is here in 1826, but the image of Lord Muktinath, made of copper, is believed to have been there since the 16th century. And the Shaligram upon which the deity is installed has been there much longer than that.

After worshiping Lord Muktinath, I paid homage to Jwalamukhi, the “ever-burning flame, ” located in the same temple complex. The existence of this flame is said to be supernatural. I could certainly see no apparent cause for it nor indications that it had been tended or nurtured by devotees. According to one legend it was the result of a penance performed by Lord Brahma invoking fire on water.

Night fell with a chilling cold. After looking long and hard for a place to sleep close to the temple complex, I finally found a rather expensive hotel which was more costly because it was supplied with goods airlifted in from outside. I was happy to pay the extra money for the heat alone. When the sun sets in this part of the world–even during the warmest part of the year–heat is a valuable commodity. Happily, while that night was freezing cold, I remained warm.

It was almost noon the next day when I stopped for lunch at a hotel in Kagbeni on my way home. Kagbeni is a charming town filled with people who come to perform shraddha (ancestor worship). Local residents contend that there is no place on the Earth as sacred as Kagbeni for honoring the ancestors.

As I left Kagbeni for Jomsom in the afternoon, the wind along the Gandaki River was blowing at its peak. Although this part of Nepal is notorious for fierce winds, this was just about as bad as it gets. When the government established a wind power plant here about ten years ago to produce electricity, the project was abandoned when the plant itself blew away.

As I walked, the wind was so strong I had to apply the full weight of my body into it just to move ahead, even slowly. I was constantly holding my face in my hands to guard against the piercing sand that was biting every square inch of my exposed skin. When I reached Jomsom in the late afternoon, I was relieved at first. Then I thought: “Oh dear! Time to get back on that plane.” Consoling myself with the thought that the blessings I had received from Lord Muktinath would always be with me even if I perished in flight, I promised myself that, if I lived to tell this tale, I would. And so I did.