Decades after the violent expulsion of the Kashmir Pandits from the Kashmir Valley, peace has largely been restored and the region’s historic tradition of interreligious harmony has reasserted itself, as witnessed by a new Sharda Temple opening just feet from the Line of Control, sponsored by Sringeri Shankaracharya Mutt in Karnataka and assisted by local Muslims

By Choodie Shivaram, Kashmir

Late last april, i saw a photo a friend had posted online—a picture of him with family at the new Sharda Temple in Teetwal, Kashmir. Just a few months earlier I had learned the 572-pound Ma Sharda murti, created for the temple by the renowned Sringeri Shankaracharya Mutt, would soon be transported by car to Kashmir. I took photos and interviewed Ravindra Pandita and others, thinking to put the story together for Hinduism Today. After seeing my friend’s post, I contacted the magazine editors and arranged to cover not only the new temple but also a few among the numerous temples of antiquity in Kashmir Valley.

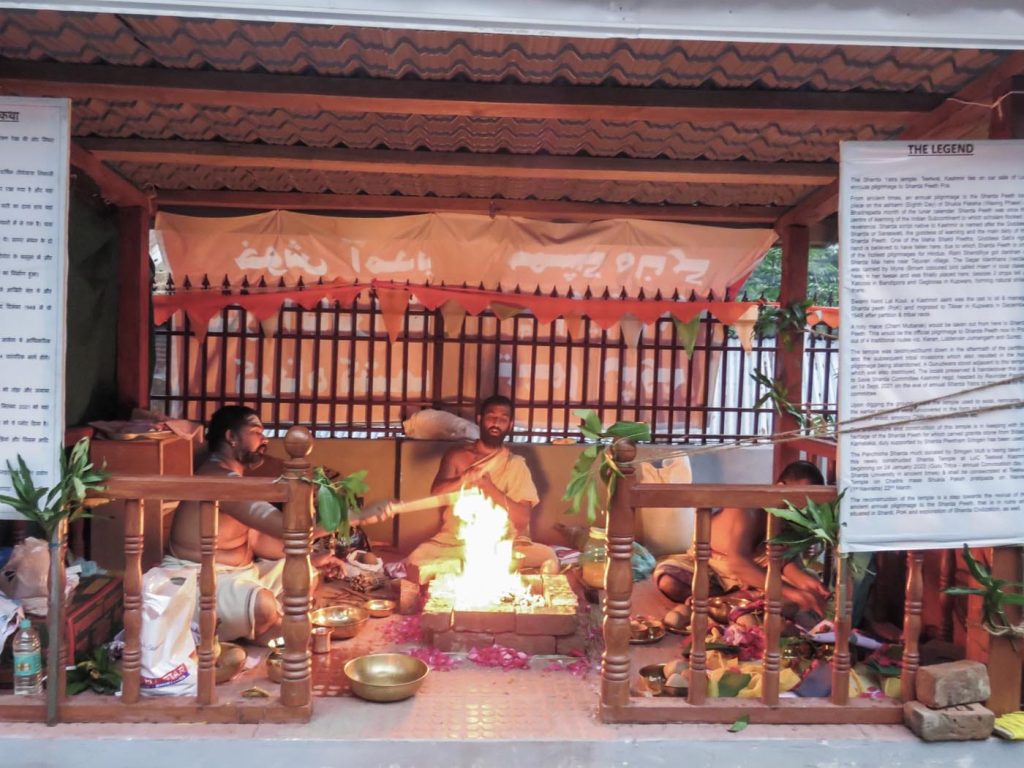

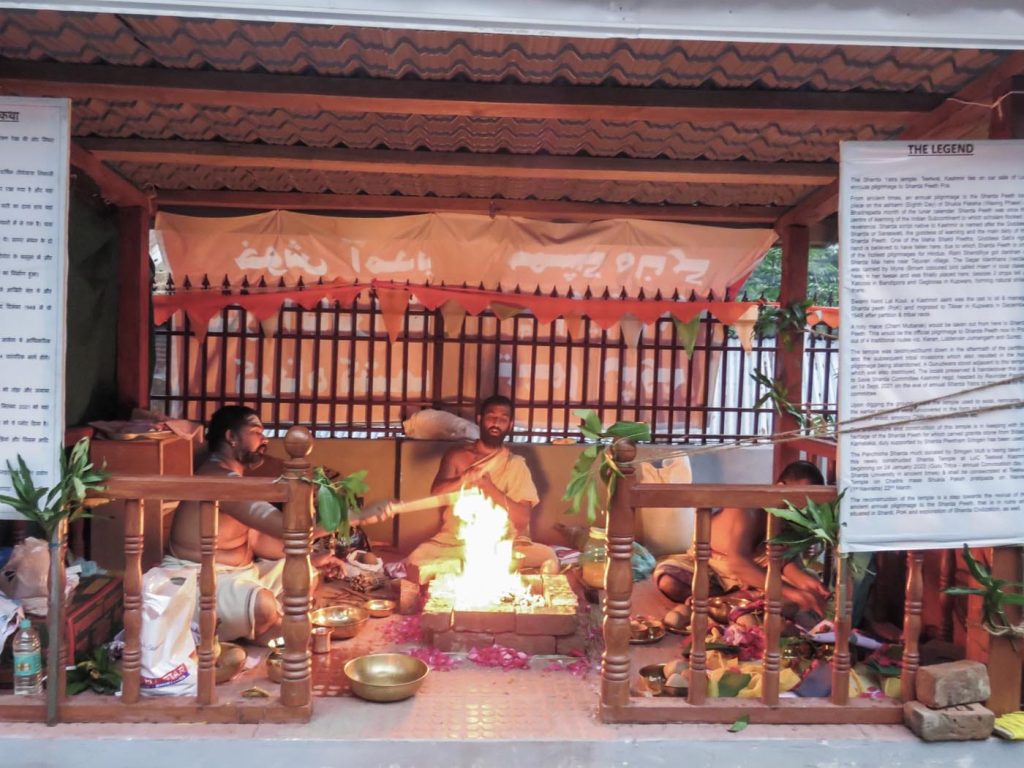

Friends learning of the assignment were shocked, concerned for my safety, and I soon stopped telling anyone I was heading to Kashmir. I booked my tickets and packed my bags. The temple was scheduled for consecration on June 5 by the Sringeri Mutt’s junior pontiff, Sri Vidhushekhara Swamiji. He was accompanied by a team of priests who conducted the pre-consecration rituals plus several officials of the mutt.

Kashmir itself, these days, is as safe or unsafe as any other region in India. After 30-plus years, schools are open and running without break, businesses are operational as in any other city, people move around freely, the economy is on the upswing, and the general feel-good factor among people is high. Religious worship in all communities is back to normal. Tourists have returned in force—20 million in 2022 alone! With no fears or doubts, and an ambitious list of temples to visit in addition to the new Sharda Temple at Teetwal, I embarked on my journey. Somewhat unexpectedly, my husband joined me, having felt Ma Sharda was beckoning him.

Kashmir as a destination is always exciting to the traveler. Every inch of the land seems magical. This journey was to be different. My agenda did not include the popular Gulmarg hill station, boat rides on the pristine Dal Lake, Shikara rides and sightseeing at Sonmarg. Instead, in addition to the Sharda Temple at Teetwal, we traveled into the interior of Kashmir to visit dozens of temples in eight of its ten districts, many of them dreaded as terrorist hideouts some years back. I also visited the popular Shankaracharya Hill Temple, Marthand Sun Temple and the Mattan Sun temple ruins. In this article, however, we will focus on the creation of the Sharda Temple at Teetwal, because it is the perfect case study in showing how much Kashmir has changed in recent times.

Sharda Peeth, Abode of the Goddess

Namaste Sharade Devi, Kashmira Puravasini—“Salutations to Goddess Sharda Who abides in Kashmir.” This prayer to the Goddess of Learning from the Saraswati Rahasya Upanishad is one of the first to be taught to a child. The hymn avows Kashmir as the abode of Goddess Sharda, the Kashmiri name for Saraswati.

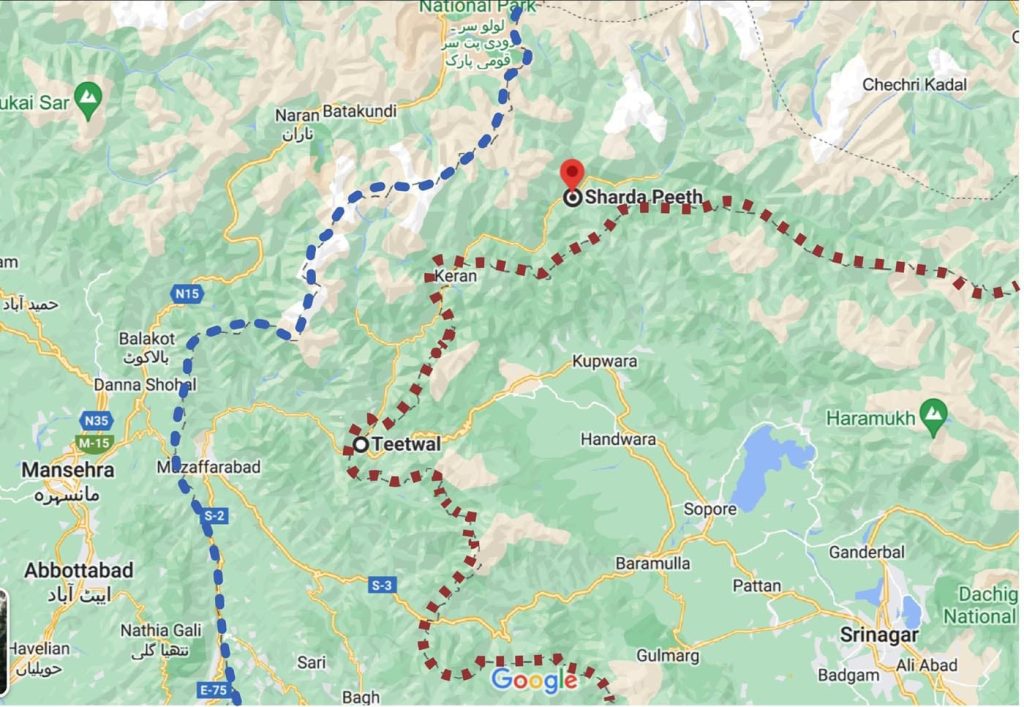

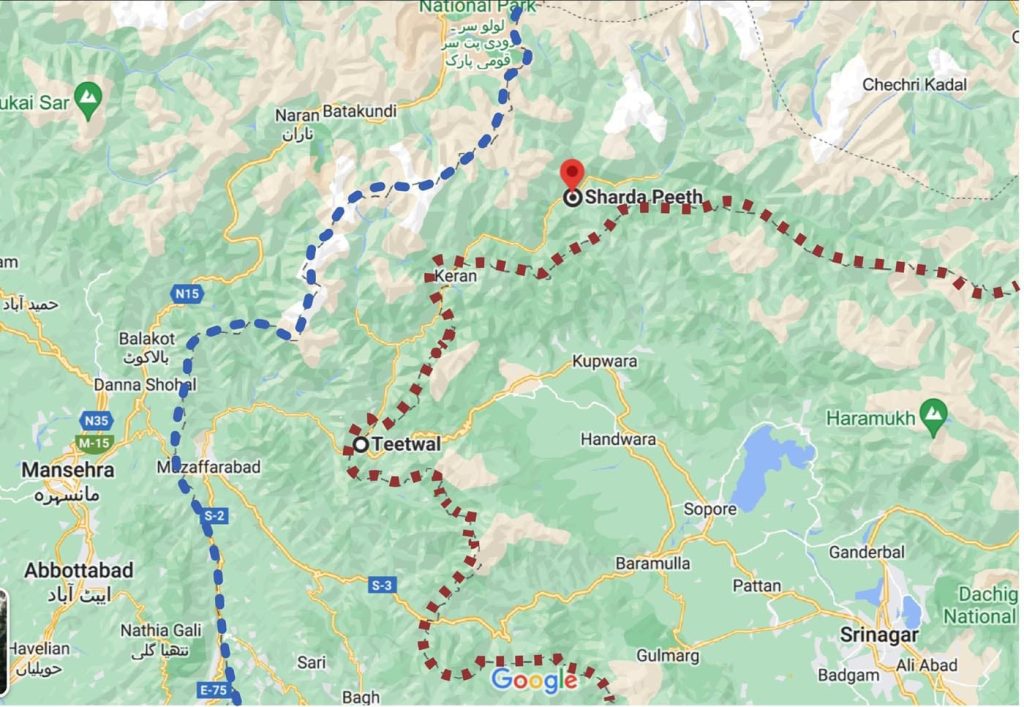

As children, we knew little of Kashmir and nothing of Sharda Peeth. Its ruins are in Sharda village on the Kishanganga River, 5.6 miles inside the Line of Control (LoC) in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK) about 70 miles north of Teetwal, which is just on the India side of the LoC. Prior to Partition, Teetwal was a historic camping point of the annual pilgrimage to Sharda Peeth.

Sharda Peeth, a major Shakti temple, was one of the most prominent universities of Vedic knowledge and learning between the 6th and 12th centuries ce, when it was known as Sarvagna Peeth. Scholars from all over the subcontinent congregated here. It was a repository of invaluable Vedic texts and the source of the Sharada script. It housed the famed Sharda University and was the foundation of Sharda civilization.

Sharda Peeth is synonymous with Adi Shankara, the foremost proponent of Advaita Vedanta philosophy, who ascended the throne of knowledge here. Sringeri Mutt in Karnataka, closely tied to Sharda Peeth, is formally known as Dakshinamanaya Sri Sarada Pitham, the first and southernmost of the four main monastic centers established in India by Adi Shankara in the 7th century. Its two main temples are Vidyashankara to Siva and Sharda Amba temple to the Goddess.

The ancient Sharda Peeth was desecrated and reduced to ruins by invaders. A powerful earthquake is said to have further damaged the structure. Still, enough of the temple remained that worship continued until late 1948. The last Hindu saint resident at Sharda Peeth was Swami Nandlal Maharaj, who is deeply revered by Kashmiri Pandits. Prakash Swami Bhat was the last priest. Despite raging atrocities inflicted on Hindus after Partition, the saint refused to leave the temple. In December 1948, Swami Nandlal and Prakash were forced to return to the Indian side of Kashmir. Thereafter, the temple was vandalized, leaving just a stone shell, and was no longer visited by Hindus.

Kashmiri Pandits Ravinder Pandita, Mohan Kumar Monga (an international entrepreneur turned renunciate), S. K. Koul and a few others have set out to revive the traditional Sharda pilgrimage, forming the Save Sharda Peeth Committee of Kashmir in 2018. They are asking that a corridor be opened through PoK so that Indian citizens (presently forbidden to enter the area) can visit Sharda Peeth. A precedent for such a corridor was set in 2019 with the establishment of the 3.4-mile Kartarpur Corridor, allowing pilgrims from India to visit the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib near Lahore in Pakistan from the Gurudwara Dera Baba Nanak—both revered sites in the Sikh tradition.

The Save Sharda Peeth Committee of Kashmir comprises three Muslims, one Sikh and five Hindus. They have engaged with the governments of Pakistan and India and connected with supportive locals in both countries to bring forward the Peeth’s importance, origins, people, habitation, religious practices and present site conditions. They have made progress toward establishing the corridor. Significantly, just a week before the murti of Goddess Sharda reached Teetwal from Karnataka, the government of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (a separate entity from the government of Pakistan itself, subordinate to it) passed a resolution calling for the opening of a corridor. “The Goddess is with us,” Ravinder Pandita exclaimed when he heard the news. They have also gained support from local Muslims in Sharda village, who provided him with small stones and soil from the site. One of the stones has been installed in the new temple, and some of the soil was used in the rituals for the Ram Temple construction in Ayodhya in 2020.

How the Teetwal Temple Came to Be

Prior to Partition, there were four traditional routes to Sharda Peeth. The main route included Teetwal along the Kishanganga River. The pilgrimage, an annual event in the months of August and September, would take seven days to cover the 70 miles and end with the singing of Adi Shankara’s song (since adopted as an anthem by the Pandits), Leela Rabda Stapita Khala Lokan, at the Sharda Temple.

Until 1947, Teetwal was famous as a flourishing trade center. The Qabali raids immediately after Partition changed all that. The raiders, tribals from the Pashtun territory supported by the Pakistan army, invaded Kashmir, attacking and killing people irrespective of the community they belonged to. None were spared. People’s homes were looted and set on fire. The raiders desecrated and burned temples, mosques and gurudwaras. People fled in fear. The devastation was intense. A prosperous town with the largest market in the country and a robust economy, where Hindu-Muslim unity was impenetrable, was reduced to wreckage.

Nearly eight decades later, the Save Sharda Peeth Committee was denied permission to enter PoK and visit Sharda Peeth, so they decided to offer prayers at Teetwal in an attempt to restart at least part of the annual Sharda yatra. On September 14, 2021—after receiving the necessary permits from the local administration, since Teetwal is at the LoC—the team reached Tangdar, a small town about three miles before Teetwal.

Monga describes their experience. “As we reached Tangdar, we were in for a big shock; there were some Muslims from Teetwal to receive us. There were no Hindus in Teetwal at the time. They garlanded us and escorted us to a youth center, gave us refreshments and said they were waiting for us. They said there is a property in Teetwal they have been protecting and wanted to hand it over to us. This is a land where a temple and a Sikh gurudwara existed prior to 1947. We had no idea of the existence of a temple here. They wanted us to build a temple there, less than a mile from the Kishanganga River, even though this was never on our agenda! Our Kashmiri community would disbelieve us if we informed them of building a temple at the LoC, after the Pandits were mostly forced out in 1990.”

The Teetwal residents took the visitors to the site where the temple had existed, and from that moment there was no looking back. “I realized that the Goddess is manifesting. I couldn’t speak, I couldn’t stop my tears. It was a miracle,” shared Monga. The mission took a new course. A temple and gurudwara had to be built.

The team headed to the four mutts established in the four quarters of India by Adi Shankaracharya and approached the respective pontiffs with the project to build a Sharda Temple at Teetwal. With over 6,000 square feet of land transferred to the Save Sharda Trust, they had to take the project to fruition—arranging finances, logistics and support on the traditions to be followed. Monga narrated: “Sringeri Peetham Jagadgurus concurred that the temple had to be built. They extended complete support for the Teetwal Sharda Temple, including the panchaloha (“five-metal”) murti. I realized Sharda Peeth had not ceased to exist; the scholastic Vedic culture was still predominant in Sringeri. Adi Shankaracharya had brought the sandalwood murti of Sharda from Kashmir and consecrated it here at Sringeri. Now Mata desires to be sent back to Kashmir from Sringeri.”

Gowrishankar, Administrator of Sringeri Mutt, told me, “Ravinder Pandita met me in 2017 seeking support for holding a public meeting at the Shankar mutt premises to enlighten people about Sharda Peeth and their mission to revive it. Then in 2021 he informed me that they had acquired a piece of land at Teetwal and had to build a Sharda Temple there. I assured them that Sringeri Mutt would support the project.”

Sringeri Mutt guided the team on construction of the temple. The junior pontiff, Vidhushekhara Bharati Mahaswamiji, suggested a granite structure that would remain for posterity. The temple was built and consecrated in consonance with the Shastras. The temple has four doors, signifying the four mutts established by Adi Shankara, just as the original Sharda Temple is said to have had four doors representing the four directions. “It is believed that Adi Shankara entered Sharda Peeth from the southern gate before he ascended the throne. To signify this, we have placed the Deity facing south,” Gowrishankar explained.

The Construction Process

Sagar Gudigara, a silpi (sculptor) from Magadi, Karnataka, was entrusted with the task of carving the granite—this in the midst of the Covid pandemic. By August 2022, the stones were dispatched to Kashmir, and the temple was completed in October. The labor force and construction was managed by local Muslims. Aiyaz Khan, a resident of Teetwal, oversaw construction and ensured that the temple was completed in record time.

Challenges included crossing mountain regions 12,000 feet above sea level. At one point, the pillars had to be cut into smaller portions since they could not be ferried across a bridge in the mountains. In May 2022, agitation broke out owing to the killing of a Kashmiri Pandit priest, Rahul Bhat. Threats were received to halt construction of the temple, and the committee decided to put it on hold. It was risky to bring the silpis to Teetwal after they had arrived in Srinagar.

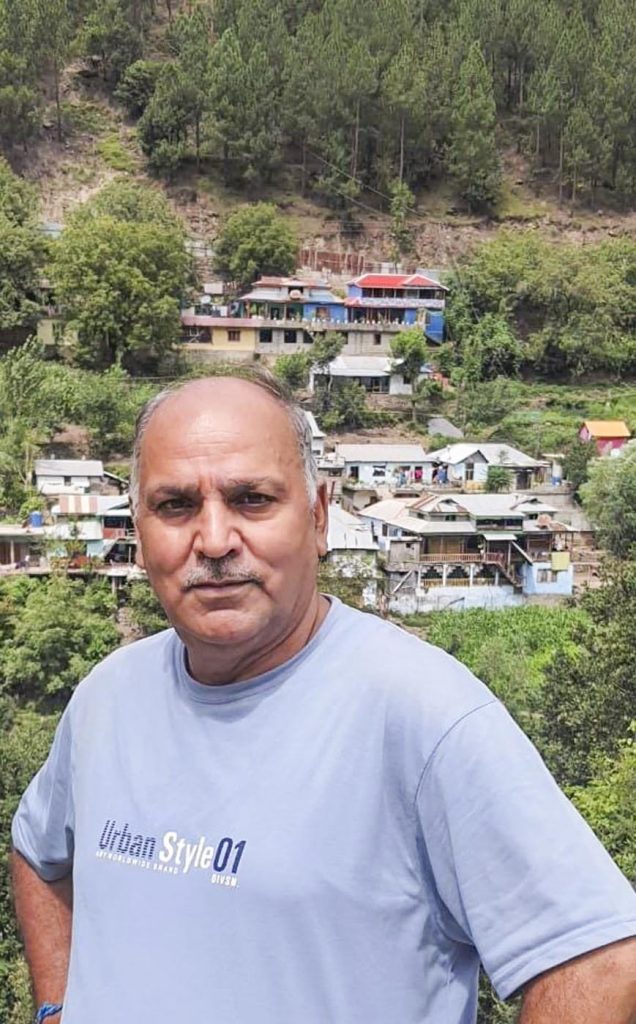

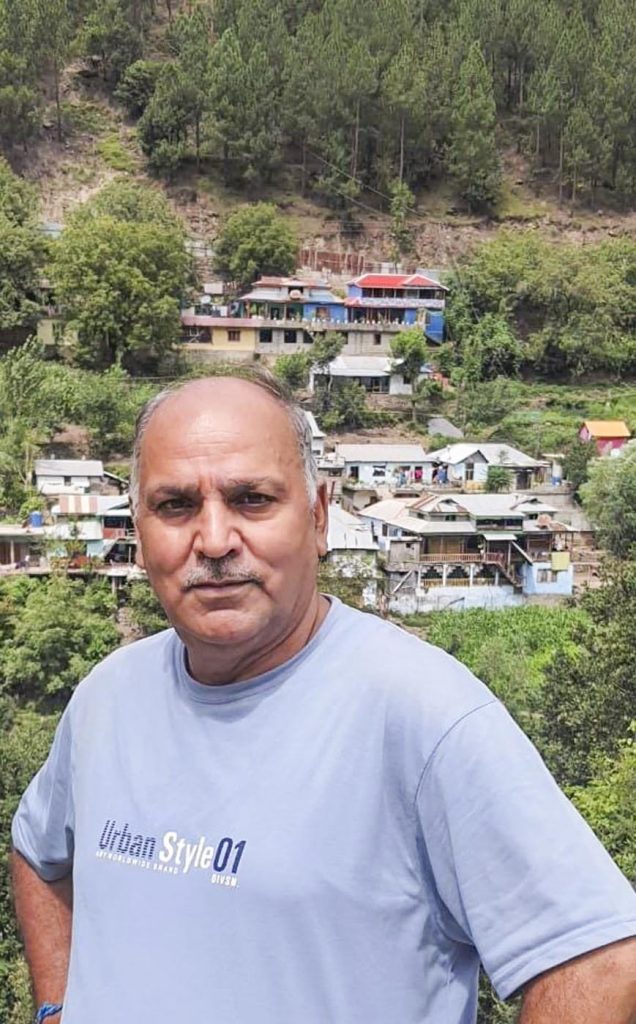

Koul, who worked directly with the laborers, told me: “That’s when I decided that nothing will stop the construction. I was not afraid of anything. Even if I were to die, I will die for the Goddess. I decided to stay at Teetwal until the temple was completed. Mongaji also joined me. I vowed to protect the masons and silpis. I took personal responsibility, picked them up from the airport and drove them to Teetwal in my personal vehicle without security. I stayed with them for three months, took care of their accommodation, food and security. I left Teetwal only after the temple was completed and I had put the silpis back on the flight to Bengaluru. This temple is a miracle. Can you imagine me, a 65-year-old, helping move granite slabs weighing 370 to 440 pounds? Stone slabs weighing 1,800 pounds could not be moved without a crane, but heavy machinery was not allowed into Teetwal. We took Sharda’s name and lifted it with the help of a hand winch. During construction, I could see the Goddess moving around the vicinity riding on a tiger. It gave me the strength and confidence that the Goddess was making Her temple.”

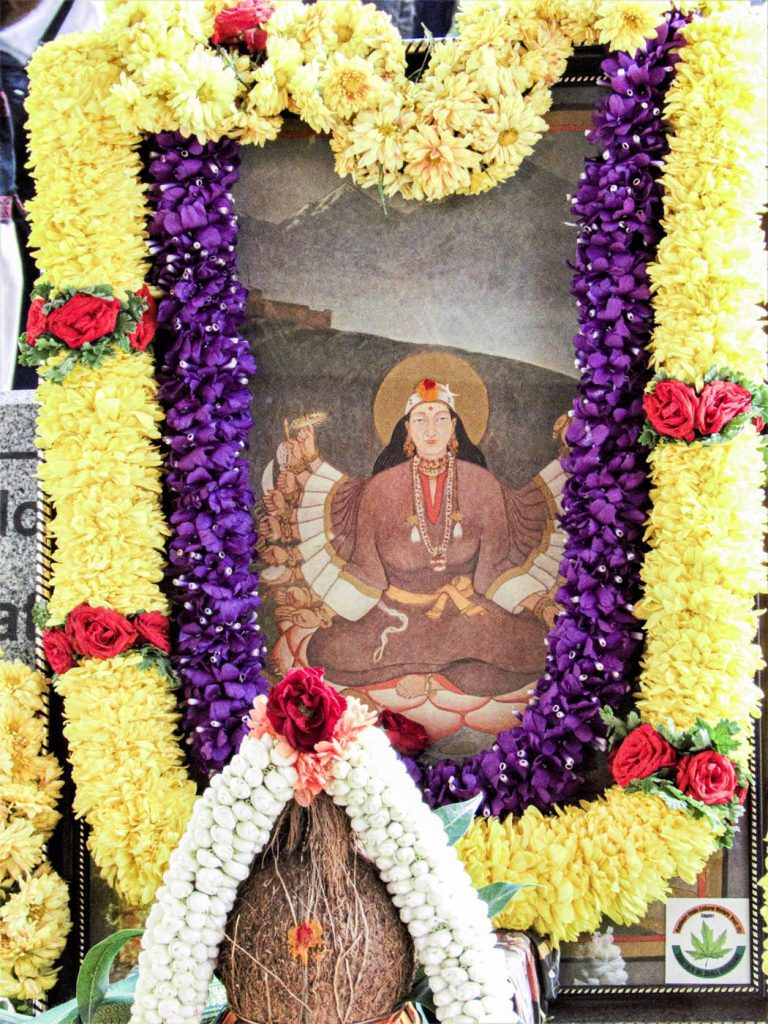

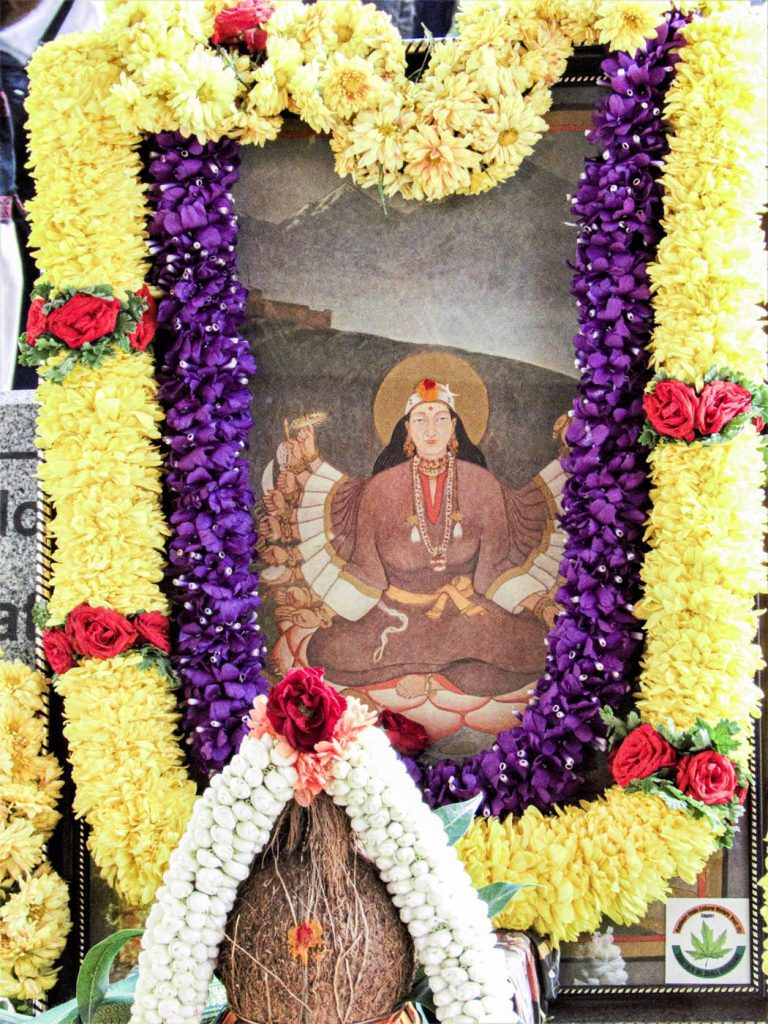

The 572-pound panchaloha murti of Goddess Sharda, a replica of the Deity in Sringeri, now sits majestically in the sanctum sanctorum of the temple. This murti and that of Adi Shankaracharya were given to the temple by the Sringeri Mutt. The Deities were handed over to the Save Sharda Committee on January 24, 2023, in a formal ceremony, then traveled nearly 2,800 miles by road to Teetwal in an SUV driven by Kashmiri Pandits. Stopping over at various cities to enable devotees to pay obeisance, the murtis reached Teetwal on March 21, 2023. The next day they were placed in the sanctum sanctorum of the temple. The temple complex also has a small prayer room housing the murti of Swami Nandalal Maharaj and a Sivalinga with saligramas. The room vibrates with devotees singing bhajans.

The Sharda murti is imposing. The expression on Her face exudes compassion and benevolence. Her smile is captivating. She is the very epitome of motherly love and grace. Her demure smile welcomes Her children and gentle palms blessed them. Seeing Her even in a photo brings warmth to the heart, courage to the mind, and calmness to the soul. One instantly connects with Her.

“It’s a great work of art, and we felt good,” says Vishwas Hedge, whose team created this masterpiece. “We followed the Silpa Sastras meticulously while creating the murti. After completion we prayed to the Goddess to forgive us for any shortcomings. While making the murti we recite a shloka that gives the description of the Deity and Her accompanying features,” says Sivakumar, one of the artisans.

The eyes and smile of the Deity are crucial. They reveal the skill of the silpi. “An auspicious time is fixed before we set the eyes and smile of the Deity, netra milana as we call it. We observe austerities and wear traditional saffron clothes. Only the working artisans are allowed in the workshop. We recite prayers and then set the face. Sometimes we receive guidance in our dreams,” says Harish, one of the artisans who worked closely on shaping the face of the Deity. “We had no idea that the murti was going to Teetwal, to the place where Sharda belongs. We got to know only after the murti was ready. It is historic and we felt that all these years of our work have been sanctified by this creation.”

Formal Installation

The official consecration of the temple was performed on June 5, 2023, by the Sringeri junior pontiff, Vidhushekhara Bharati Mahaswamiji. His presence was seen as a significant message. “After Adi Shankaracharya, the pontiff from Sringeri is the first one to worship the Goddess Sharda in Kashmir. In a region that had fallen to disrepute owing to militancy, the Jagadguru’s presence reaffirmed faith in humanity and brotherhood among all religions, sending out a strong message of unity,” says Monga. At Teetwal, Vidhushekhara Bharati walked through the lanes of the village surrounding the temple, went close to the banks of Kishanganga River and addressed a large gathering of devotees and residents who had come for the consecration. The presence of Muslims, not only from Teetwal but surrounding villages, was significant, all of them wearing a badge of Sharda on their chest.

Reflections

The four days I spent at Teetwal in the overpowering presence of the Goddess, being in the company of Seshu, Monga and other devotees where the conversations were all about the Goddess or the great spiritual gurus of Kashmir, and partaking in the bhajan sessions, are a treasure in my memory trove.

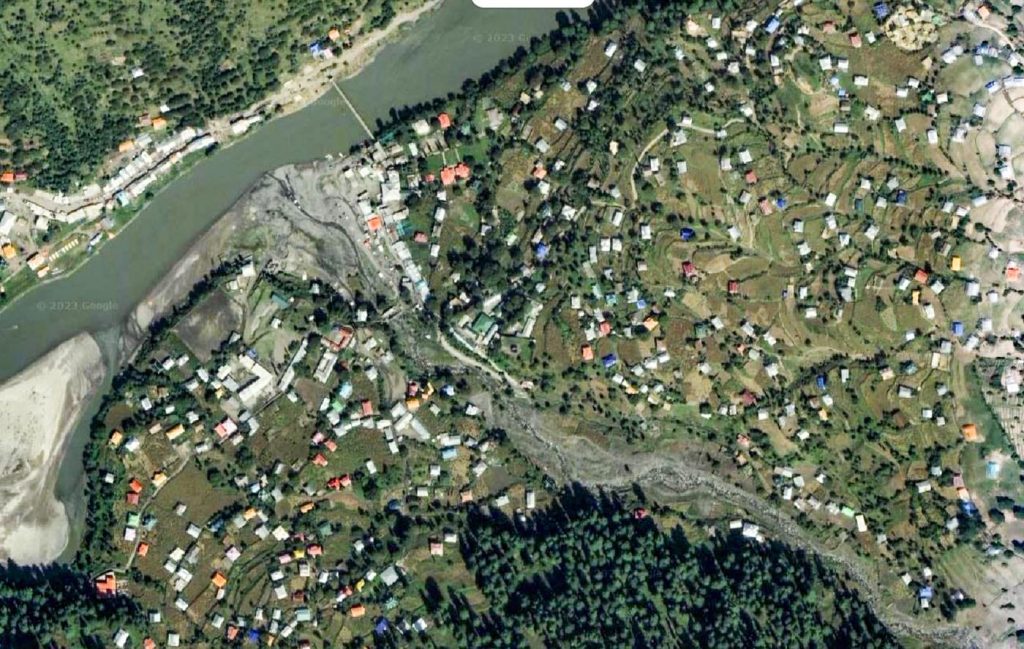

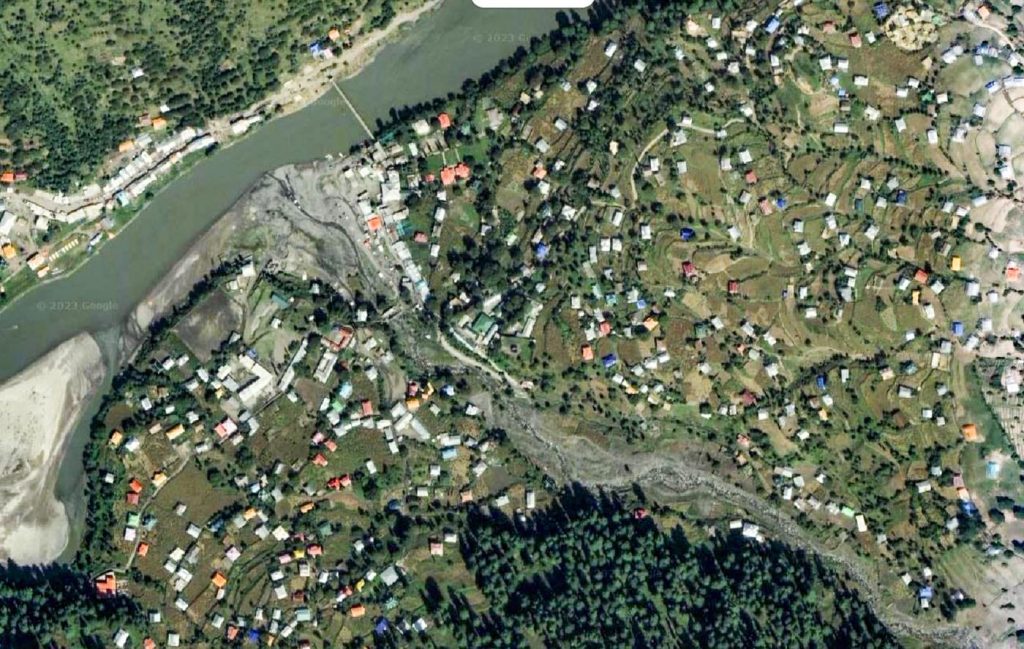

Today Teetwal reverberates with the ringing of temple bells, blowing of the conch and Vedic recitation. Sharda is well settled in Teetwal, attracting innumerable visitors every day from all over the world. The economy of the village is seeing a boom, with enhanced business opportunities in transport and accommodation. The villagers have opened their homes for homestays. There is a ghat on the riverbank to facilitate devotees to have a holy dip. Improved lodgings, food facilities for yatris, an imposing arch at the entrance of the road leading to the temple and residential accommodation for the priest are works under consideration.

The upbeat mood of Sharda’s arrival is visible among people not only in Teetwal but surrounding towns, too. The Sharda Cup cricket tournament, hosting 40 teams from all over Kashmir, was played at Teetwal. The Sharda yatra resumed on September 23, with everyone’s prayer that the corridor to Sharda Peeth be approved soon. Even the Pakistanis are talking about making the original Sharda Peeth a tourist destination.

The holy mace, symbol of the pilgrimage, was taken to the nearby bridge across the river. There is a white line in the middle separating India from PoK; crossing it without authorization is forbidden. At this point, worship was offered to the river Kishanganga.

Tremendous efforts are being made by Ravindra Pandita and his team to have a corridor to Sharda Peeth opened. Inspired by them, prominent people have been urging the government to allow the corridor. Recently Dr. Karan Singh, a senior Indian politician and descendant of the Dogra royal family of Kashmir, made a representation to the Prime Minister of India seeking his involvement to enable Hindus to visit Sharda Peeth in PoK and offer prayers. With the Save Sharda Movement gaining momentum, the impact made by the temple at Teetwal and the presence of the Goddess, it is hopefully only a matter of time before access to Sharda Peeth enables devotees to reclaim their lost heritage. At least our children have realized the importance of Sharda Peeth and all that connects with it.

Adi Shankara and Sharda Peeth

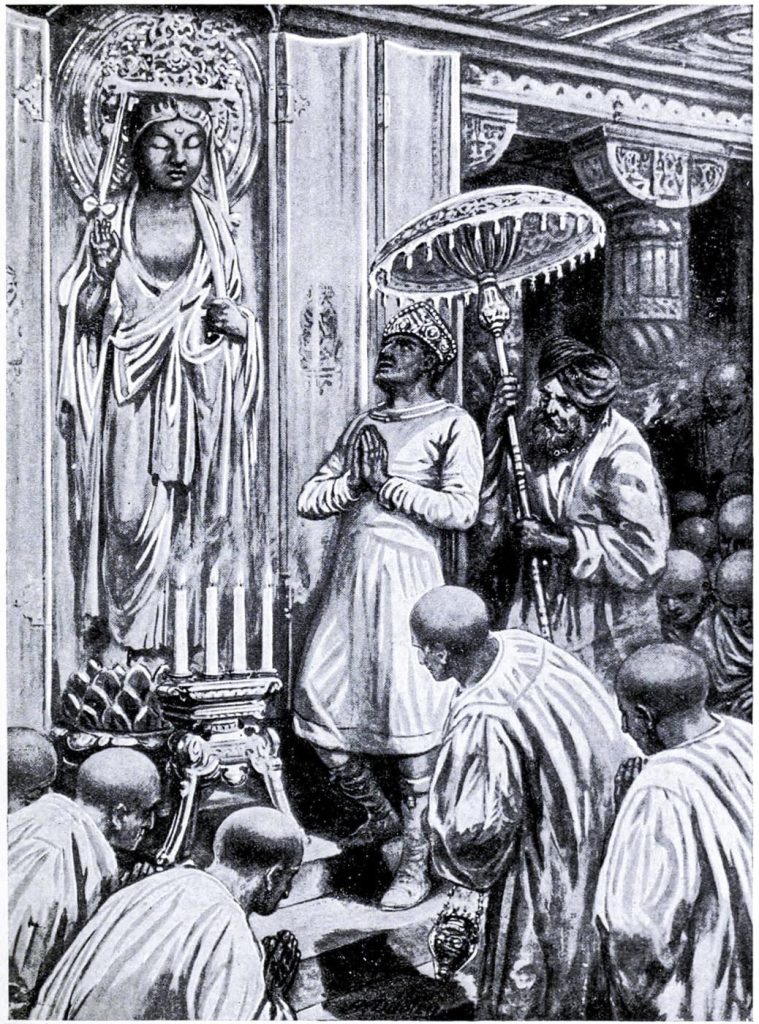

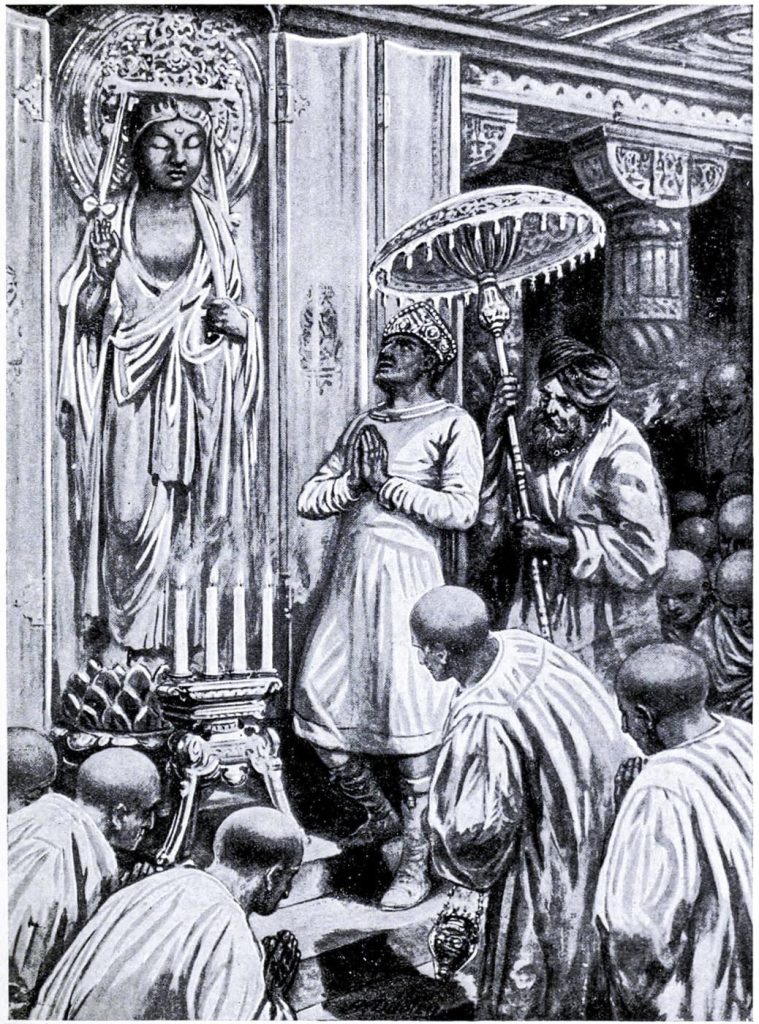

Adi Shankaracharya ascended the throne of knowledge at Sharda Peeth. According to his 14th century biography, “Shankaracharya came to know about a temple with four gates for Goddess Sharda in the Kashmir region. The temple was famous for its Throne of Omniscience (Sarvajna Peetham), signifying that only an omniscient one can sit on it. Shankara felt that he was divinely ordained to attempt to ascend the Sarvajna Peetham through the southern door and headed to the Sharda Temple in Kashmir. People greeted Sri Shankara enthusiastically and hailed his advent as a lion ruling over the forest of Advaita.

“Shankara approached the southern entrance. There was an intense debate spanning a few days where Shankara was questioned by scholars of all other religions and schools of thought. Only when they were convinced of his eligibility did they approve of his ascent to the throne. Holding the hand of Padmapada, the Acharya was about to ascend the Throne of Omniscience when he heard the voice of Goddess Sharda. The Goddess challenged him that it is not enough if a person is omniscient but he should also be pure. Shankara cannot be said to be pure because of his stay at the palace of King Amaruka (where he took over the king’s body). To this challenge, the Acharya answered that from his birth he had done no sin with this body of his, and what was done with another body will not affect this body. Sharda became silent, accepting the explanation, and allowed Acharya to ascend the Throne of Omniscience, to the ovation of the people there. The heavenly conch shells blew, kettle drums sounded like roaring of the oceans and flowers rained down in praise of Sri Shankara.” Adi Shankara, foremost proponent of Advaita philosophy, became synonymous with Sharda Peeth. The sandalwood murti of Sharda long worshipped the Vidyashankara temple at Sringeri in Karnataka is believed to have been brought here by Adi Shankaracharya from Sharda Peeth.

The 10th-century Iranian scholar Al-Biruni and 16th century historian Ab-L-Fazl are said to have made references to the sandalwood murti of the Deity at Sharda Peeth. Some versions say that the murthi was lost during a powerful earthquake. The stone slab with Sharda yantra (mystical diagram) remained at the site till October 1947.

Teetwal’s Voices

Aiyaz Khan, Save Sharda Committee Member

“Ravindra Pandita created a great bonding, bringing Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims together with this temple. I offered to take over the task of constructing the temple and gurudwara. He said it would take time, maybe even six years. I gave him my word, he trusted me and it was completed in less than a year. Our entire district of Karnah has welcomed the construction. We revere Sharda as the Goddess of Learning; we revere Her the most. In 2016 I had been to Sharda Peeth (in PoK); it is in shambles. I felt very sad seeing it.

“Before Partition, there was a dharmashala, temple and gurudwara in Teetwal. Pilgrims would camp here at night. The next morning the Chari Mubarak (holy mace) would officially leave from here to Sharda Peeth. When they came back after performing puja and havan, the Chari Mubarak would be left here. We want to install the sandalwood Sharda now at Sringeri at Sharda Peeth and have a corridor be opened for the Sharda yatra.

“My children are very excited about the temple. My 11-year-old son Momen loves to go there and light the lamp. When the temple opened, he ran in, put his head to the ground then rang the bell in full enthusiasm. After Sharda Mata has come here, She has transformed the lives of people. Religious tourism is progressing. I’m a Muslim sitting on the border of what was a disturbed region, and I have built the temple joining hands with a Kashmiri Pandit. This shows the harmony that exists here.

“We want the Pandits to come back. In the 90s they shouldn’t have gone to Jammu, they should have come to Teetwal, Uri or Tangdar. We would have protected them like brothers. Today we plead with them to come back, our homes are open to them, we will protect you.”

Akhtar Ali Khan, 103, Bahadurkot, Teetwal

“Teetwal’s history is glorious. It was a prosperous trade center; there was a hospital, tax collector’s court and a number of government departments. There was an endless market with stores open past midnight where you could shop for hours together. Hundreds of people would come from Muzaffarabad (now in PoK) to trade here. There were 6,000 Hindus, about 5,000 Muslims and many Sikhs. Each owned a large number of shops with big showrooms. Hindu-Muslim unity was at its best; we never knew these divisions of religion. There was a big Sharda temple here whose priest was Pandit Bhagwan Das. We would celebrate all the festivals together. We used to play holi with great excitement, even the priest would join us. Janmashtami was a big festival. Sardar Prem Singh, Jambal Ram, Lala Ram, Nadam Ram, Santrapal, Sanderam, Lala Gulisthan, Manthral, they were all my friends, I have no words to say how good they were. I am very happy that the temple has been constructed here. I want my Hindu brethren to come back and start living here. I want the road to Sharda to be opened so that we can take our people to Sharda Peeth. It is my dream to get back those good old days.”

Alifuddin Waqar, Retired Forester, Teetwal

“My father told me a gurudwara and temple existed here; it was a beautiful place. There used to be an informal council where social and personal problems would be discussed and elders from the community would give solutions. We are thrilled about the Sharda Temple here. We are seeing a lot of changes; it has started bringing a lot of good people from all over India. The most important thing that matters for us is peace. This temple is an example of hard work, dedication and harmony.

“A temple should be constructed at Sharda Peeth itself; like-minded people on that side (PoK) who care for Sharda civilization should raise their voices. There was a Sharda university there. People from all over the world irrespective of religion came to this place. We want our Hindu and Sikh brethren to come back and live here. We want nothing else.”

Those Who Stayed

Unknown to many is the grit and courage of those Kashmiri Pandits who did not leave the valley during the exodus in the early 1990s. It is estimated that eight thousand or more Pandits stayed and endured the turbulent times, while 200,000 fled. I realized that all along I had been seeing Kashmir from only one perspective—the geopolitical angle. My visit revealed a multidimensional form including not only the dangers of cross-border terrorism but, more importantly, the suffering of people irrespective of religion, the bonding and camaraderie of all communities that existed even in the times of adversity and continues to this day, and the resolve of Pandits to stay connected to their roots.

I met nearly a dozen Pandits whose families stayed behind. One was Ashok Kumar. He was seven when his parents chose to not leave their village of Wusan in the Barambulla district. Wusan had sixteen happily settled Hindu families. When the outburst of militancy happened, Ashok said, “ten families fled. The neighbors and the village head pleaded with our parents and the remaining families not to leave. They said the village will be deserted and will get a bad name that we chased away the Hindus. They promised to protect us, and they did. Till this day we have had no problem at all. We all live in harmony. Our temples here have been safe and rituals have continued uninterrupted.” He lives today in the house that his forefathers built.

Another was Vijay Kumar Sas, a resident of Srinagar. Living in the midst of terror-torn Srinagar when militancy peaked in 1989, Vijay’s father, Pran Nath Sas, resolved not to leave. His philosophy was “not to die before death comes,” said Vijay, who was in class seven at the time. “A lot of my classmates had been indoctrinated into militancy. One day I met a classmate on the street and asked him why he had skipped his exams, and in a jiffy he pointed a loaded gun at me. It intrigued me; the only time I had seen a gun was in films,” says Vijay, who was then just turning 13. Being the only son, his parents packed him off to Jammu to be with his grandparents. Vijay went to a migrant camp school in Jammu and returned to settle in Srinagar after completing his studies.

Life was not easy for his parents. Vijay’s mother courageously stood by her husband in his decision not to leave. On many occasions terrorists barged into their house and held a gun at his father’s neck. Pran Nath Sas fought them back each time. “My father was once abducted by militants to be killed. Muslims from our neighborhood rescued him,” says Vijay. “In 1999, when I came back here, I got a threat letter from a terrorist group asking me to leave the valley in a week else I would be killed. My father showed the letter to a colleague who worked with the judge in the session’s court. The person who wrote the letter was nabbed the next day.” Vijay drew inspiration and courage not only from his father but also from people who fought against the onslaught of terrorism while being in the midst of it. “It’s easy to engage in activism now, but in the 90s, in the kind of situation then in Kashmir, it was unimaginable,” said Vijay.

Vijay has been actively engaged in fighting for the rights of Kashmiri Pandits, protection of temples and reservation for Kashmiri Pandits in education. He founded the organization Kashmiri Pandit Sangharsh Samiti (KPSS), the only non-migrant organization in Kashmir. Since 2007 he has had a battery of lawyers help him in these legal battles. The group has filed nearly 25 cases to get temple lands released from encroachers and secure them. Vijay explains, “When the exodus happened, temples became vulnerable and people started laying claim to them. It was not just some Muslims, but people with criminal backgrounds from outside the state who usurped temple properties and have even illegally leased them out. There are nearly 800 temples in Kashmir, but no official list. As a result of our case, in 2010 the court ordered the Revenue Department to create a formal authorized index of all the temples.”

Pandits who have stayed back often faced uncertainties and wondered whether they took the right decision not to flee. Those who migrated to Jammu did not have a comfortable life either. What has not been reported is that Hindus in Jammu subjected the migrants to ridicule and abuse. People like Vijay have seen it all. “Life has many ups and downs. One would think that we are living a cushy life in Kashmir, but reality is different—a lot of tension, a lot of gunfire from both sides.” Four years ago his name was on a targeted killing list. One of his advocate friends, a Muslim, ensured his name was taken off the list. Vijay has seen a lot of support from the Muslims. “People from outside come and sow hatred here. But we live here together through thick and thin. We have to: this is our homeland.”

Kashmir’s History

By Choodie Shivaram, Bengaluru

Kalhana’s immortal 12th century-ce work rajatarangini describes Kashmir thus: “Kailasa is the best place in the three worlds; Himalayas is the best part of Kailasa and Kashmir is the best part in the Himalayas.” Poets and scholars describe Kashmir’s magnetic beauty, calling it a valley of happiness. In his 1935 book Archaeological Remains of Kashmir, Pandit Anand Koul writes, “Kashmir is considered the balm for tired minds and sore hearts.”

A land where the Gods manifested and powerful kings ruled, Kashmir abounds in antiquity, and is characterized by grandeur, intellectual wealth and piety. The Greek philosopher Ptolemy mentions with clarity the location of Kasmiriya. Chinese travellers Hieun Tsiang (in India from 631 to 633 ce) and Wukong (759 ce) “made accurate records of the ancient temples here,” reports Pandit Anand Koul in his book. From Kalhana’s Rajatarangini to Walter Lawrence’s Valley of Kashmir (1885), historical texts record the growth and times of this land of mystics.

Kalhana’s work was continued by Pandit Jonaraja, who wrote the history of Kashmir up to the troubled mid-15th-century times of the last Hindu dynasty and the time of Sultan Sikander. “Most headmen of villages had access to translations of Rajatarangini. They repeated stories of Kalhana’s chronicle, and the uneducated villagers have a general idea of the history of their country,” writes Anand Koul.

In the 3rd century bce, when Kashmir was part of Ashoka’s empire, Buddhism became the state religion. Ashoka’s son Jaloka, a worshiper of Siva, reverted to practice Saivism. One of the most famous kings of Kashmir was Lalitaditya, who ruled from 697 to 738 and was much loved by his people. With artisans brought from across the territories he had conquered, Lalitaditya built magnificent temples and adorned them with gold acquired during his conquests. The Marthand Sun temple near the Kashmiri city of Anantnag is a grand example; even the ruins speak of Lalitaditya’s monumental contribution to temple architecture.

The first appearance of Islam in Kashmir is believed to be a failed invasion attempt by Tartar Khan Dalcha in 1128. History took a bitter course with the entry of Sikander in 1394. He undertook a fierce campaign of destruction, shattering murtis, desecrating Hindu temples and slaughtering thousands of Hindus. Sikander deputed an entire force for a full year to destroy the Marthand temple.

Kashmir came under the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar during 1555-1605. In the mid-17th century, Aurangzeb rained terror on the people of Kashmir. Hindu Pandits from Kashmir sought help from Guru Tegh Bahadur, the ninth Sikh guru, to protect them from Aurangzeb’s oppressive policies. Guru Tegh Bahadur set out to rescue the Pandits but was beheaded by Aurangzeb in 1675.

The death of Aurangzeb in 1707 enabled the Durrani Empire of Afghanistan to consolidate power in Kashmir. “The miseries of the Kashmiris increased, resulting in penury, degradation and slavery,” according to Kashmiri scholar Prithivi Nath Kaul Bamzai.

In 1819 Kashmir came under the rule of the Sikhs after Maharaja Ranjit Singh sent his troops to liberate the people of Kashmir from the tyrannical Afghans. After the death of Raja Ranjit Singh in 1839, the Dogra chief Gulab Singh, who was with Ranjit Singh and later helped the British, was installed as the sovereign of Kashmir after signing the treaty of Amritsar in 1846. The last Dogra ruler was Hari Singh (father of the Indian politician, Dr. Karan Singh), who signed the Instrument of Accession, merging Kashmir with the Indian Union after the Partition of 1947.

The story of Kashmir’s spiritual heritage is equally complex. For Hindus, Kashmir is a holy land which finds extensive mention in Ramayana, Mahabharata, Kautilya’s Artha Shastra, Patanjali’s Mahabhashya, Kalidasa’s works and innumerable literary and historical texts of yore. Called Bharatha Shira Shikara, the crown of India, Kashmir has been home to rishis, sages, scholars and innumerable saints and mystics, even to this day.

The 10th-century scholar-saint Acharya Abhinavgupta (950–1016) was one of the greatest proponents of Kashmir Shaivism. His works continue to be researched throughout the world. His student Kshemendra’s proficiency in mathematics, astrology, social sciences, Buddhist philosophy, Vedanta, Saiva Siddhanta, mantra shastra, music, painting and other arts is unrivaled. The 14th-century poet Lalleshwari (1320–1392, also known as Lallade) is what saint Akka Mahadevi is to Karnataka. At 24, she renounced everything, including clothes, and was deeply revered as a saint who touched people’s lives. Her compositions in the local dialect are sung even today.

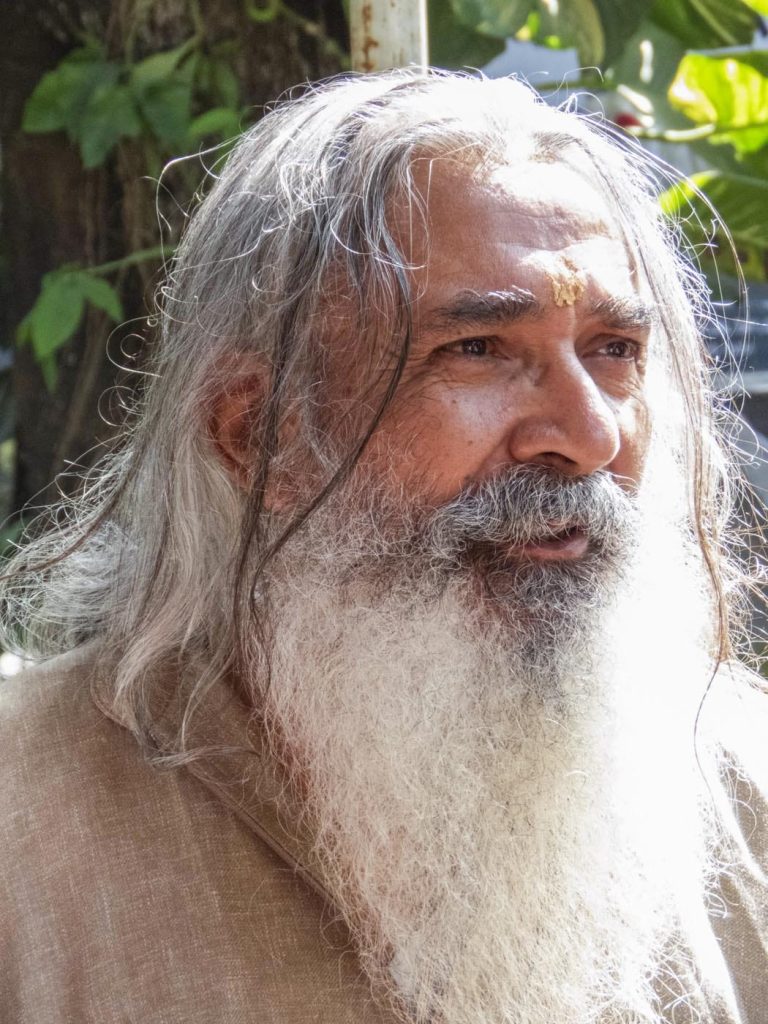

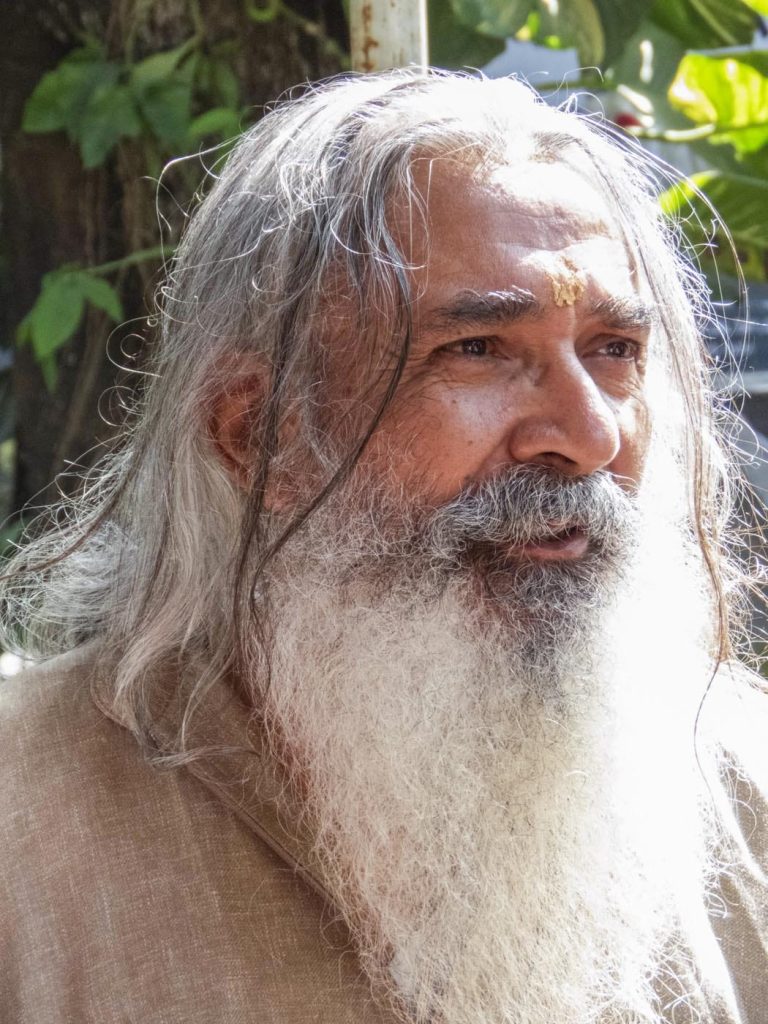

Kashmir has been home to innumerable mystics and saints. In this spiritually magnetic land, Sufism took on a uniquely syncretistic identity, blending Sufi Islam with Advaita and Shaivite Hinduism. The very name of the Sufi order that was birthed in Kashmir—the Rishi Order—reflects this harmonious identity, which forms a part of the larger Kashmiriyat, the religious harmony that undergirds much of Kashmir’s traditional culture and manifests not only in mutual respect but participation in the festivals of each religion by all. Kashmir’s long list of spiritual leaders includes Swami Nandlal Maharaj (1896–1973), Swami Mast Baba (1930–2023), Lakshman Jhoo Maharaj (1907–1991) and Swami Gopinath Maharaj (1898–1968).

Distinct to Kashmir is the Sharada lipi (script), which dates back to the 7th century and is said to have originated from the Brahmi lipi. Sharada lipi is regarded as the base for the Gurumukhi script prevalent today. Nagari lipi, from which Devanagari evolved, also traces its origins to Sharda lipi. The ninth-century mathematics manuscript Bhakshali Hastha Prathi is written in Sharada lipi. Baijanatha Prashasti, found in Kangra Valley in Kashmir, is considered the oldest text in Sharada lipi, dating back to 804 ce.

Despite or perhaps due to its beauty, glorious heritage and wealth of knowledge, history has not been kind to Kashmir. The invasions followed by persecution created periods of turmoil. Kashmir became a bone of contention after Partition. In October 1947, the Qabali raids by tribals from Pakistan shook the very foundations of harmony. Homes and religious places of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs alike were destroyed and burnt. People were brutalized and prosperous towns became impoverished. After Maharaja Hari Singh belatedly agreed to accede Kashmir to the Indian Union, the Indian army swung into action and successfully drove the raiders back. Unfortunately, the Pakistani-usurped land became a disputed territory now known as Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). Cross-border terrorism, which started in 1947, has haunted Kashmir ever since.

Between 1989 and 1993, nearly 200,000 Kashmiri Hindus fled the valley owing to heightened militancy, threats and aggression. Close to eight thousand Pandits dared to stay back and brave the hostilities. The situation has dramatically improved in recent years, in particular since 2019, following the abrogation of Article 370 of the Indian constitution. This article had given what was intended to be temporary, semi-independent status to Jammu and Kashmir. Unfortunately, the terms of Article 370 were not conducive to stable government.

Today’s Kashmir is a story of harmony between communities; it is a scene of development and progress. Temples are being rebuilt and cared for by the Muslims. In 2023, after 33 violence-riddled years, a Muharram procession by the Shia community, previously a platform for separatist protests, was conducted peacefully. Live coverage of Janmashtami celebrations from temples, grand Krishna processions in various cities, and celebration of Guru Nanak’s birthday on a grand scale, brought back the old fervor of togetherness. In the words of Dr. Touseef Ahmad Bhat, a socio-environmental activist, “Abrogation of article 370 has brought significant changes in Kashmir, integrating it closely with rest of the nation and fostering the economic growth of the state. There is a robust enhancement of infrastructure development, building bridges, highways, ring roads and upgrading the airport. Many schemes have been initiated towards industrial development, tourism, hospitality industry, manufacturing and information technology, offering incentives and subsidies to attract investors.”

He continued, “There has been a record-breaking influx of tourists to Kashmir. Last year we had nearly twenty million tourists visiting the valley. Schemes for home stays and border tourism have grown, showing that peace is returning to the valley. Empowerment of women has made gains, and minority groups have been provided equal rights with opportunities, enabling them to participate more actively in social and economic ventures. There are a lot of fashion shows and such activities going on, which had been a distant dream for women here. Implementation of central government schemes for education, health care, rural development and poverty alleviation (something that was denied to us all these years owing to vested interests) have improved the quality of life and contributed to the overall development.”

About the Author

Choodie Sivaram has been a journalist for over three decades. She writes on current affairs, policy matters, constitutional and legal issues, heritage and culture. She wrote and directed the documentary, “At the Altar of India’s Freedom—The INA Veterans of Malaysia,” produced by the Indian High Commission in Malaysia. Choodie holds degrees in journalism and law.