A Youthful Primer About Hinduism’s Eight-Limbed System of Meditation and Spiritual Striving

From The Teachings of Satguru Sivaya Subramuniyaswami

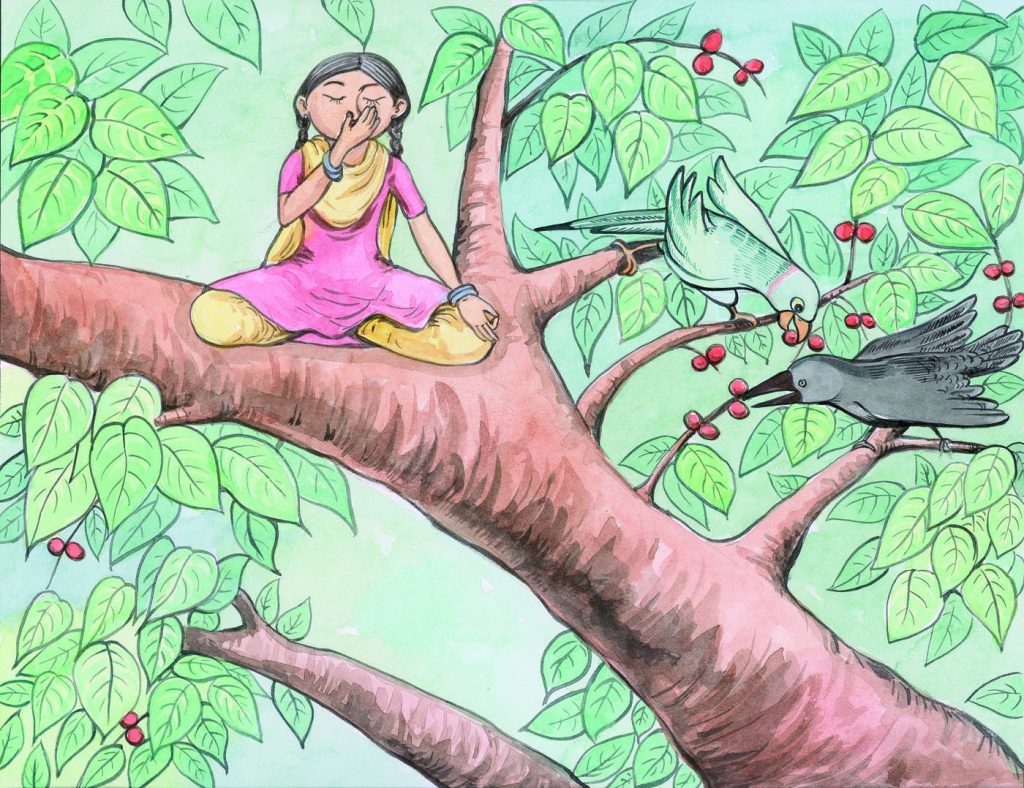

Art by Rajeev NT

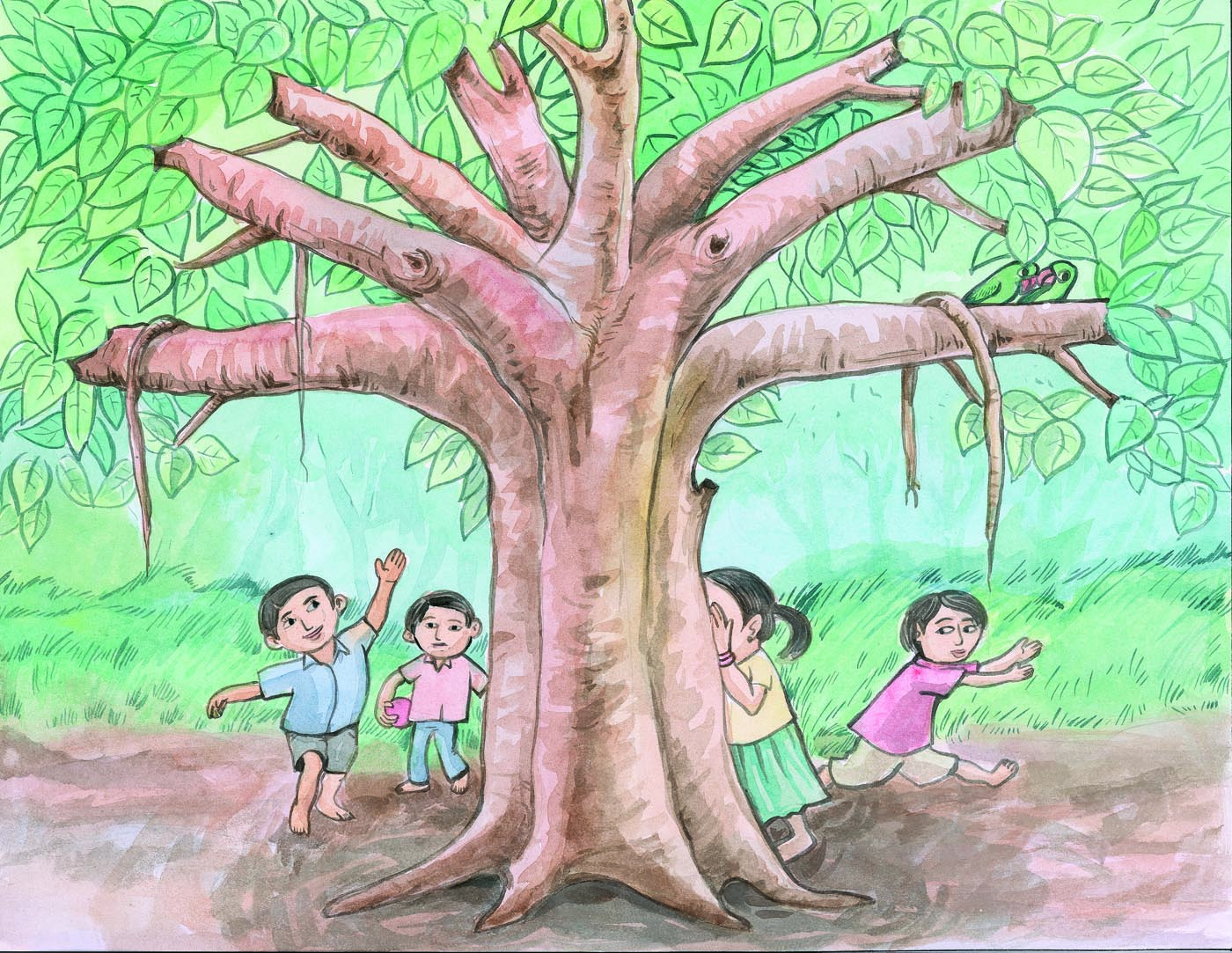

Today’s popular concept of yoga equates it with hatha yoga and the practice of the hatha yoga âsanas, or postures. Many who practice such yoga do so solely for health benefits. However, others pursue yoga, in a deeper sense, in hopes of reaping the spiritual benefits it offers. It is to these spiritual seekers who have higher consciousness as the goal of their yoga that this Educational Insight is directed. Here we describe the path called râja yoga, the regal (râja) means to enlightenment, a classical, meditative system that is one among the numerous yogas practiced in Hinduism. Technically, it is termed ashtânga (eight-limbed) yoga, a name coined by Sage Patanjali, because it consists of eight stages, represented in our illustrations of the village tree with eight limbs. These stages are: yama (restraint), niyama (observance), âsana (seat or posture), prânâyâma (mastering life force), pratyâhâra (withdrawal), dhâranâ (concentration), dhyâna (meditation) and samâdhi (contemplation and God Realization). It is worth noting that yama (the restraints) and niyama (the observances) precede âsana (hatha yoga postures), but they are omitted in most yoga classes today. That is unfortunate, as this ethical basis is of utmost importance. We can liken these eight limbs to a tall building. The yamas are the first part of the foundation, like the steel; and the niyamas are the second part, like the cement. Together they provide the support a skyscraper needs to stand. Åsana, prânâyâma and pratyâhâra are like the lower floors, dhâranâ and dhyâna are the middle ones, and samâdhi is the topmost floor, the stratum of realization and illumination.

Satguru Bodhinatha Veylanswami

Yama: Restraints

“Restraint.” Virtuous and moral living, which brings purity of mind, freedom from anger, jealousy and subconscious confusion which would inhibit the process of meditation.

“Yama is abstention from harming others, from falsehood, from theft, from incontinence and from greed.”

Sage Patanjali, II, Sûtra 30

Sutra translations are from How to Know God, The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood, copyright 1953 by the Vedanta Society of Southern California

It is true that bliss comes from meditation, and it is true that higher consciousness is the heritage of all mankind. However, the ten restraints and their corresponding practices are necessary to maintain bliss consciousness, as well as all of the good feelings toward oneself and others attainable in any incarnation. These restraints and practices build character. Character is the foundation for spiritual unfoldment.

The platform of character must be built within our lifestyle to maintain the total contentment needed to persevere on the path. The great rishis saw the frailty of human nature and gave these guidelines, or disciplines, to make it strong. They said, “Strive!” Let’s strive to not hurt others, to be truthful and honor all the rest of the virtues they outlined.

The twenty restraints and observances are the first two of the eight limbs of ashtânga yoga, constituting Hinduism’s fundamental ethical code. Because it is brief, the entire code can be easily memorized and reviewed daily at the family meetings in each home. The yamas and niyamas are cited in numerous scriptures, including the Sandilya and Varâha Upanishads, the Hatha Yoga Pradîpikâ by Gorakshanatha, the Tirumantiram of Rishi Tirumular and the Yoga Sûtras of Sage Patanjali. All of these ancient texts list ten yamas and ten niyamas, with the exception of Patanjali’s classic work, which lists just five of each. Patanjali lists the yamas as: ahimsâ, satya, asteya, brahmacharya and aparigraha (noncovetousness); and the niyamas as: saucha, santosha, tapas, svâdhyâya (self-reflection, scriptural study) and Isvarapranidhâna (worship).

Each discipline focuses on a different aspect of human nature, its strengths and weaknesses. Taken as a sum total, they encompass the whole of human experience and spirituality. You may do well in upholding some of these but not so well in others. That is to be expected. That defines the sâdhana, therefore, to be perfected.

The ten yamas are: 1) ahimsâ, “noninjury,” not harming others by thought, word or deed; 2) satya, “truthfulness,” refraining from lying and betraying promises; 3) asteya, “nonstealing,” neither stealing nor coveting nor entering into debt; 4) brahmacharya, “divine conduct,” controlling lust by remaining celibate when single, leading to faithfulness in marriage; 5) kshamâ, “patience,” restraining intolerance with people and impatience with circumstances; 6) dhriti, “steadfastness,” overcoming nonperseverance, fear, indecision, inconstancy and changeableness; 7) dayâ, “compassion,” conquering callous, cruel and insensitive feelings toward all beings; 8) ârjava, “honesty, straightforwardness,” renouncing deception and wrongdoing; 9) mitâhâra, “moderate appetite,” neither eating too much nor consuming meat, fish, fowl or eggs; 10) Saucha, “purity,” avoiding impurity in body, mind and speech.

Niyama: Observances

“Observance.” Religious practices which cultivate the qualities of the higher nature, such as devotion, cognition, humility and contentment—giving the refinement of character and control of mind needed to follow spiritual disciplines and ultimately plunge into samâdhi.

“The niyamas are purity, contentment, austerity, study and devotion to God.”

Sage Patanjali, II, Sûtra 32

The niyamas are 1) hrî, “remorse,” being modest and showing shame for misdeeds; 2) santosha, “contentment,” seeking joy and serenity in life; 3) dâna, “giving,” tithing and giving generously without thought of reward; 4) âstikya, “faith,” believing firmly in God, Gods, guru and the path to enlightenment; 5) Isvarapûjana, “worship of the Lord,” the cultivation of devotion through daily worship and meditation; 6) siddhânta Sravana, “scriptural listening,” studying the teachings and listening to the wise of one’s lineage; 7) mati, “cognition,” developing a spiritual will and intellect with the guru’s guidance; 8) vrata, “sacred vows,” fulfilling religious vows, rules and observances faithfully; 9) japa, “recitation,” chanting mantras daily; 10) tapas, “austerity,” performing sâdhana, penance, tapas and sacrifice.

In comparing the yamas to the niyamas, we find the restraint of noninjury, ahimsâ, makes it possible to practice hrî, remorse. Truthfulness brings on the state of santosha, contentment. And the third yama, asteya, nonstealing, must be perfected before the third niyama, giving without any thought of reward, is even possible. Sexual purity brings faith in God, Gods and guru. Kshamâ, patience, is the foundation for Isvarapûjana, worship, as is dhriti, steadfastness, the foundation for siddhânta Sravana. The yama of dayâ, compassion, definitely brings mati, cognition. Årjava, honesty—renouncing deception and all wrongdoing—is the foundation for vrata, taking sacred vows and faithfully fulfilling them. Mitâhâra, moderate appetite, is where yoga begins, and vegetarianism is essential before the practice of japa, recitation of holy mantras, can reap its true benefit in one’s life. Íaucha, purity in body, mind and speech, is the foundation and the protection for all austerities.

The yamas and niyamas and their function in our life can be likened to a chariot pulled by ten horses. The passenger inside the chariot is your soul. The chariot itself represents your physical, astral and mental bodies. The driver of the chariot is your external ego, your personal will. The wheels are your divine energies. The niyamas, or spiritual practices, represent the spirited horses, named Hrî, Santosha, Dâna, Åstikya, Isvarapûjana, Siddhânta Sravana, Mati, Vrata, Japa, and Tapas. The yamas, or restraints, are the reins, called Ahimsâ, Satya, Asteya, Brahmacharya, Kshamâ, Dhriti, Dayâ, Årjava, Mitâhâra and saucha. By holding tight to the reins, the charioteer, your will, guides the strong horses so they can run forward swiftly and gallantly as a dynamic unit. So, as we restrain the lower, instinctive qualities through upholding the yamas, the soul moves forward to its destination in the state of santosha. Santosha, peace, is the eternal satisfaction of the soul. At the deepest level, the soul is always in the state of santosha. Therefore, hold tight the reins.

Asana: Posture

“Seat or posture.” A sound body is needed for success in meditation. This is attained through ha†ha yoga, the postures of which balance the energies of mind and body, promoting health and serenity.

“Åsana is to be seated in a position which is firm but relaxed. Åsana becomes firm and relaxed through control of the natural tendencies of the body, and through meditation on the Infinite.”

Sage Patanjali, II, Sûtras 46–47

Success in meditation requires the ability to sit in a comfortable posture, for long periods, without moving. Proper posture is necessary because the very simple act of equalizing the weight and having it held up by the spine causes you to lose body consciousness. Sit up nice and straight with the spine erect and the head balanced at the top of the spine.

By sitting up straight, with the spine erect, the energies of the physical body are transmuted. Posture is important, especially as meditation deepens and lengthens. With the spine erect and the head balanced at the top of the spine, the life force is quickened and intensified as energies flood freely through the nerve system. In a position such as this, we cannot become worried, fretful, depressed or sleepy during our meditation. Learn to sit dynamically, relaxed and yet poised.

Inwardly observe this posture and adjust the body to be poised and comfortable. Feel the muscles, bones and the nerve system. This posture is possible sitting in a chair, on a cushion, or on your knees. Ideally, a competent meditator will be able to cross the legs for meditation, either in full or half lotus. The hands are held in the lap, the right hand resting on the left, tips of the thumbs touching softly. In all cases, the posture should be natural and easy, and not cause discomfort, which is distracting during meditation. Look inwardly at the currents of the body. Observe their flow.

If you just sit without moving, and breathe, the inner nerve system of the body of your psyche, your soul, begins to work on the subconscious, to mold it like clay. Awareness is loosened from limited concepts and made free to move vibrantly and buoyantly into the inner depths where peace and bliss remain undisturbed for centuries.

The meditative poses are part of a larger system called hatha yoga, a system of bodily postures, or âsanas, created as a method for the yogi practicing yoga for long hours each day, performing japa and meditation, to exercise and keep the physical body healthy so that his meditations could continue uninhibited by disease or weakness. The purpose of hatha yoga today again is the same—to keep the physical body, emotional body, astral body and mental body harmonious, healthy and happy so that awareness can soar within to the heights of divine realization. In our hatha yoga we work with color, we work with sound and with the subtle emotions and feelings of the body when going from one âsana to another. Each âsana carefully executed, with regulated breathing, the visualization of color and the hearing of the inner sound, slowly unties the knotted vâsanâs within the subconscious mind and releases awareness from there to mountaintop consciousness.

Pranayama: Breath Control

“Harnessing prâna.” Breath control, which quiets the chitta and balances the idâ and pingalâ currents within the spine. The science of controlling prâna through breathing techniques in which the lengths of inhalation, retention and exhalation are modulated. Prânâyâma prepares the mind for deep meditation.

“After mastering posture, one must practice control of the prâ∫a by regulating the motions of inhalation and exhalation.”

Sage Patanjali, II, Sûtra 49

The entire nerve system of the physical body and the functions of breath have to be at a certain rhythm in order for awareness to remain poised like a hummingbird over a flower. Now, since the physical body and our breath have never really been disciplined in any way, we have to begin by breathing rhythmically and diaphragmatically, so that we breathe out the same number of counts as we breathe in. After we do this over a long period of time—and you can start now—the body becomes trained, the external nerve system becomes trained, responds, and awareness is held at attention.

The first observation you may have when thus seated for meditation is that thoughts are racing through the mind substance. You may become aware of many, many thoughts. Also, the breath may be irregular. Therefore, the next step is to transmute the energies from the intellectual area of the mind through proper breathing, in just the same way as the proper attitude, preparation and posture transmuted the physical-instinctive energies. Through regulation of the breath, thoughts are stilled and awareness moves into an area of the mind which does not think, but conceives and intuits.

There are vast and powerful systems of breathing that can stimulate the mind, sometimes to excess. Deep meditation requires only that the breath be systematically slowed or lengthened. This happens naturally as we go within, but can be encouraged by a simple method of breathing called kalîbasa in Shûm, my language of meditation. During kalîbasa, the breath is counted: nine counts as we inhale, hold one count, nine counts as we exhale, hold one count. The length of the beats or the rhythm of the breath will slow as the meditation is sustained, until we are counting to the beat of the heart.

Controlling the breath is the same as controlling awareness. They go hand in hand. During meditation, the breath, the heartbeat, metabolism—it all slows down, just like in sleep. Therefore, the practice of prânâyâma and regulation of the breath, the prânas, the currents of the body, should really be mastered first. We need this preparation of the physical body so that the physical and emotional bodies behave themselves while you are in a deep state of meditation.

You can spend hours or years working with the breath. Find a good teacher first, one who keeps it simple and gentle. You don’t need to strain. Start simply by slowing the breath down. Breathe by moving the diaphragm instead of the chest. This is how children breathe, you know. So, be a child. If you learn to control the breath, you can be master of your awareness.

Pratyahara: Withdrawal

“Withdrawal.” The practice of withdrawing consciousness from the physical senses first, such as not hearing noise while meditating, then progressively receding from emotions, intellect and eventually from individual consciousness itself in order to merge into the Universal.

“When the mind is withdrawn from sense objects, the sense organs also withdraw themselves from their respective objects and thus are said to imitate the mind. Then arises complete mastery over the senses.”

Sage Patanjali, II, Sûtra 54

Here is a step-by-step system of pratyâhâra that you can use to begin each meditation for the rest of your life. Simply sit, quiet the mind, and feel the warmth of the body. Feel the natural warmth in the feet, in the legs, in the head, in the neck, in the hands and face. Simply sit and be aware of that warmth. Feel the glow of the body. This is very easy, because the physical body is what many of us are most aware of. Take five or ten minutes to do this. There’s no hurry.

The second step is to feel the nerve currents of the body. Start with the feeling of the hands, thumbs touching, resting on your lap. Feel the life force going through these nerves, energizing the body. Try to sense the even more subtle nerves that extend out and around the body about three or four feet. This may take some time. When you have located some of these nerves, feel the energy within them. Tune into the currents of life force as they flow through these nerves.

The third step takes us deeper inside, as we become dynamically aware in the spine. Feel the power within the spine, the powerhouse of energy that feeds out to the external nerves and muscles. Visualize the spine in your mind’s eye. See it as a hollow tube or channel through which life energies flow. Feel it with your inner feelings. It’s there, subtle and silent, yet totally intense.

The fourth step is to draw the energy from the five senses inward in a systematic way. On the first inbreath, bring awareness into the left leg, all the way to the toes, and on the outbreath slowly withdraw the energy from that leg into the spine. Repeat with the right leg, left arm (all the way to the fingertips), right arm and finally the torso.

The fifth step comes as we plunge awareness into the essence, the center of this energy in the head and spine. This requires great discipline and exacting control to bring awareness to the point of being aware of itself. The state of being totally aware that we are aware is called kaîf. It is pure awareness, not aware of any object, feeling or thought. Simply sit in a state of pure consciousness. Go into the physical forces that flood, day and night, through the spine and body. Then go into the energy of that, deeper into the vast inner space of that, into the essence of that, into the that of that, and into the that of that. Once you are thus centered within yourself, you are ready to pursue a meditation, a mantra or a deep philosophical question. Coming out of meditation, we perform this process in reverse.

Dharana: Concentration

“Concentration.” Focusing the mind on a single object or line of thought, not allowing it to wander. The guiding of the flow of consciousness. When concentration is sustained long enough and deeply enough, meditation naturally follows.

“Concentration upon a single object may reach four stages: examination, discrimination, joyful peace and simple awareness of individuality.

Sage Patanjali, I, Sûtra 17

When we have brought awareness to attention, we automatically move into the next step, concentration. The hummingbird, poised over the flower, held at attention, begins to look at the flower, to concentrate on it, to study it, to muse about it, not to be distracted by another flower—that is, then, awareness moving. Awareness distracted, here, is awareness simply moving to another flower, or moving to another area of the mind.

Give up the idea that thoughts come in and out of your mind like visitors come in and out of your house. Hold to the idea that it is awareness that moves, rather than the thoughts that move. Look at awareness as a yo-yo at the end of a string. The string is hooked to the very core of energy itself, and awareness flows out and it flows in. Awareness might flow out toward a tree and in again, and then out toward a flower and then in again, and down toward the ground and then in again. This wonderful yo-yo of awareness—that is a good concept to grasp in order to become more acquainted with awareness. Awareness held at attention can then come into the next vibratory rate and concentrate.

Here is a simple concentration exercise. Take a flower and place it in front of you. Breathe deeply as you sit before it. Simply look at it. Don’t stare at it and strain your eyes. Simply become aware of it. Each time awareness moves to some other area of the mind, with your willpower move awareness back and become aware of the flower again. Keep doing this until you are simply aware of the flower and not aware of your body or your breath. Then begin to concentrate on the flower. That is the second step. Think about the flower. Move into the area of the mind where all flowers exist in all phases of manifestation, and concentrate on the flower. Move from one area to another—to where all stems exist, to the stem of that particular flower, to the root that that particular flower came from, and to the seed. Concentrate, concentrate, concentrate on the flower. This is what concentration is—remaining in the thought area of the particular item that you are aware of and flowing through the different color and sound vibrations of the thoughts. How does it work? The powers of concentration—it is only a name. Actually, what is happening is you are flowing awareness through the area of the mind which contains the elements which actually made that particular flower, and you are perceiving how all those elements came together. If you can concentrate sufficiently to have fifty thoughts about the flower without a single thought about anything else, you will have mastered dhârana.

Dhyana: Meditation

“Meditation.” A quiet, alert, powerfully concentrated state wherein new knowledge and insight pour into the field of consciousness. This state is possible once the subconscious mind has been cleared and quieted.

“Meditation is an unbroken flow of thought toward the object of concentration.”

Sage Patanjali, III, Sûtra 2

After we are able to hold awareness hovering over that which we are concentrating upon, we come into great powers of observation. We are able to look into and almost through that which we are concentrating upon and observe its various parts and particles, its action and its reaction, because we are not distracted. Even observation in daily life, as a result of regular participation in the practice of concentration, comes naturally. We are able to see more, hear more, feel more. Our senses are more keen and alive. Observation is so necessary to cultivate, to bring awareness fully into the fullness of meditation.

This leads us then into our very next step, meditation. Meditation and concentration are practically the same thing, though meditation is simply a more intense state of concentration. The state of meditation is careful, close scrutiny of the individual elements and energies which make up that flower. You are scrutinizing the inner layers of the mind, of how a flower grows, how the seed is formed. You are observing it so keenly that you have forgotten that you are a physical body, that you are an emotional unit, that you are breathing. You are in the area of mind where that flower exists, and the bush that it came from, and the roots and the seed and all phases of manifestation, all at the same time. And you are seeing it as it actually is in that area of the mind where the flower is that you first put awareness at attention upon, then began to concentrate upon. Then you are meditating on the actual inner area of the mind where, in all stages of manifestation, that particular species actually is within the mind.

When you are experiencing the totality of the moment, you are not aware of the past, nor are you aware of the future or anything within the externalities of the mind. You are aware of the âkâßa, the primal substance of the superconsciousness of the mind. You are able to have a continuity of intuitive findings within it and gain much knowledge from within yourself.

As you sit to meditate, awareness may wander into past memories or future happenings. It may be distracted by the senses, by a sound or by a feeling of discomfort in the body. This is natural in the early stages. Gently bring awareness back to your point of concentration. Don’t criticize awareness for wandering, for that is yet another distraction. Distractions will disappear if you become intensely interested and involved in your meditation. In such a state you won’t even feel the physical body. You have gone to a movie, read a book or sat working on a project on your computer that was so engrossing, you only later discovered your foot had fallen asleep for a half hour because it was in an awkward position. Similarly, once we are totally conscious on the inside, we will never be distracted by the physical body or the outside.

Samadhi: Union

“Union.” Sameness, contemplation, realization. The state of true yoga, in which the meditator and the object of meditation are one.

“When, in meditation, the true nature of the object shines forth, not distorted by the mind of the perceiver, that is samâdhi.”

Sage Patanjali, III, Sûtra 3

Out of meditation, we come into contemplation. Contemplation is concentrating so deeply in the inner areas of the mind in which that flower and the species of it and the seed of it and all exist. We go deeper, deeper, deeper within, into the energy and the life within the cells of the flower, and we find that the energy and the life within the cells of the flower is the same as the energy within us, and we are in contemplation upon energy itself. We see the energy as light. We might see the light within our head, if we have a slight body consciousness. In a state of contemplation, we might not even be conscious of light itself, for you are only conscious of light if you have a slight consciousness of darkness. Otherwise, it is just your natural state, and you are in a deep reverie. In a state of contemplation, you are so intently alive, you can’t move. That’s why you sit so quietly. This is savikalpa samâdhi (“union with form or seed”), identification or oneness with the essence of an object. Its highest form is the realization of the primal substratum or pure consciousness, Satchidânanda.

This, then, leads to the very deepest samâdhi, where we almost, in a sense, go within one atom of that energy and move into the primal source of all. There’s really nothing that you can say about it, because you cannot cast that concept of the Self, or that depth of samâdhi, you cannot cast it out in words. You cannot throw it out in a concept, because there are no areas of the mind in which the Self exists, and yet, but for the Self, the mind, consciousness, would not exist. You have to realize It to know It; and after you realize It, you know It; and before you realize It, you want It; and after you realize It, you don’t want It. You have lost something. You have lost your goal for Self Realization, because you’ve got it. This is nirvikalpa samâdhi (“union without form or seed”), identification with the Self, in which all modes of consciousness are transcended and Absolute Reality, Parasiva, beyond time, form and space, is experienced. This brings in its aftermath a complete transformation of consciousness.

The Chandogya Upanishad expresses it so beautifully: “The Self is below, above, behind, before, to the right, to the left. I am all this. One who knows, meditates upon and realizes the truth of the Self—such a one delights in the Self, revels in the Self, rejoices in the Self. He becomes master of himself and master of all the worlds. Slaves are they who know not this truth.” (7.25.2 The Upanishads, Prabhavananda and Manchester, p. 118).