HISTORY

EMERSON AND THE TRANSCENDENTALISTS

______________________

America’s earliest mysticism was strongly influenced by Hindu thought

______________________

“CRIME AND PUNISHMENT GROW OUT of the one stem,” wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson in his essay, Compensation. “Punishment is a fruit that unsuspected ripens within the flower of the pleasure which concealed it. Cause and effect, means and ends, seed and fruit, cannot be severed, for the effect already blooms in the cause, the end pre-exists in the means, the fruit in the seed.”

Compensation was Emerson’s interpretation of the Hindu law of karma. Long before his fellow countrymen even knew Hinduism existed, he was studying and absorbing the wisdom of the Vedas and their Upanishads, The Laws of Manu, The Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Today Emerson is honored as one of America’s most influential and original thinkers. Yet few realize how extensively his work was suffused with Oriental philosophy—especially Hinduism. Long before Swami Vivekananda’s famed sojourn to North America, Emerson was subtly weaving Hindu thought into the fabric of his scholarly writing as if it were his own. In the minds of the Western intelligentsia, he ploughed fertile fields of inspiration 50 years before Indian swamis traveled West to seed them.

Transcendentalism was a literary movement founded in 1836 by Emerson and a handful of other adventuresome American thinkers. It featured at least three authors of world stature: Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman.

Combining Romanticism with reform, Transcendentalism celebrated the spiritual potential of man by encouraging nonconformity so that, through a sense of individuality, man might be released from mass conditioning enough to intuitively experience God’s all-pervading oneness by personal efforts of unbiased and open-minded introspection. Transcendentalism emphasized the individual rather than the masses, intuition rather than reason, the forces of nature rather than the powers of man. This was radical thinking in those days, and it did not bring them immediate popularity. Yet, such outspoken abandon of accepted norms freed the authors to study the literature, religion, philosophy and culture of exotic lands far beyond their shores. Perhaps as a result of Emerson’s influence, they all eventually became fascinated by the ancient texts of Hinduism.

A Disparate Team

An irrefutable mystical bent coupled with an interest in Oriental literature may have been the only qualities the early American Transcendentalists had in common. History paints a vivid picture of disparity and dissimilarity between Emerson, Thoreau and Whitman. Yet, this very dissonance was fuel in the fire of the cause for which they had formed in the first place. Emerson remained the ring leader—staid and serene. He entered into disputes only with intellectuals on intellectual issues. He was a far more comprehensive thinker than his comrades, but less given to “putting the concepts into practice,” which was the forte of Thoreau and Whitman.

Emerson’s infatuation with the East enticed him away from an early career in the Christian ministry into a mystic search that his creative writing only partially appeased, even though it decidedly altered the course of Western thought for more than a hundred years to come.

In an essay entitled Emerson as Seen from India, written shortly after his death, Pratap Hunder Mozoomdar, a leader of the Brahmo Samaj declared: “Brahmanism is an acquirement, a state of being rather than a creed. In whomsoever the eternal Brahma breathed his unquenchable fire, he was the Brahman. And in that sense Emerson was the best of Brahmans. He shines upon India serene as the evening star. He seems to some of us to have been a geographical mistake.”

Another author and scholar, Herambachandra Maitra, suggests that the Massachusetts mystic gave Hindus assurance and faith: “Emerson appeals to the Oriental mind. He translates into the language of modern culture what was uttered by the sages of ancient India in the loftiest strains. He breathes a new life into our old faith, and he assures its stability and progress by incorporating with it truths revealed or brought into prominence by the wider intellectual and ethical outlook of the modern spirit.”

Not only is Emerson acknowledged by modern-day scholars East and West as one of the world’s greatest writers, he is also considered to be a primary influence in the development of North America’s open-mindedness toward religious tolerance, psychic interests and ethical concerns. Emerson is the most quoted American in the modern media, and his works have been translated into dozens of languages abroad. Even those who never heard of him venerate the American ideals he helped to forge, including personal achievement, character development and moral living. According to one critic, Emerson continues to be “the least limited, the most permanently suggestive” of American literary artists.

Many Hindu religious leaders came to respect the work of Emerson. Swami Paramananda of the Ramakrishna Order, for instance, frequently quoted Emerson in his lectures and even wrote a book entitled Emerson and Vedanta.

Bringing Old Laws to Life

Today it’s easy to find translations of Oriental writings. When Emerson was alive, however, things were different. Such translations were few and imperfect. International communication and travel were poor. It was rare to even hear of Hindu writings and rarer still to access them and be able to study them in depth. Emerson was able to gain much from “Hindu missionaries” like Ram Mohan Roy, who traveled to America in the early 1800s, inspired to elucidate Hinduism for the West.

“When Confucius and the Indian scriptures were made known, no claim to monopoly of ethical wisdom could be thought of,” Emerson joyfully proclaimed. “It is only within this century (the 1800s) that England and America discovered that their nursery tales were old German and Scandinavian stories; and now it appears that they came from India, and are therefore the property of all the nations.”

Emerson often presented Hindu principles in their original purity. Sometimes he would quote the scriptures directly. Through all of the elegance of his refined prose, there ever remained in his work an unpretentious commitment to the wisdom of the words rather than the crafting of them, as if the core of his motivation was more about leaving behind diaries of personal practice and discovery than legacies of literary greatness. Even his finished works read like ongoing revelations “to be continued.”

“Always pay!” he exclaimed, heralding the truths of karma and dharma. “First or last you must pay your entire debt. Persons and events may stand for a time between you and justice, but it is only a postponement. You must pay at last your own debt.”

“Thou canst not gather what thou dost not sow; as thou dost plant the trees, so will it grow. Whatever the act a man commits, of that the recompense must be received in corresponding body.”

Emerson more than echoed ancient wisdom. It was his pleasure and a good portion of his genius to be able to penetrate and expand upon the timeless truths. In this sense, his works were shared meditations.

“Every act rewards itself—or, in other words, integrates itself—in a twofold manner,” he asserted. “First, in the thing, or in real nature and, secondly, in the circumstance, or in apparent nature. Men call the circumstance the retribution. The causal retribution is in the thing and is seen by the soul. The retribution in the circumstance is seen by the understanding. It is inseparable from the thing, but it often spreads over a long time and so does not become distinct until after many years. The specific stripes may follow late after the offense, but they follow because they accompany it.”

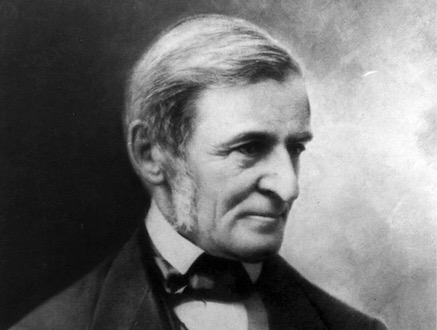

ARCHIVE PHOTOS

RALPH WALDO EMERSON, THE PHILOSOPHER

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was born in Boston, Massachusetts, but he spent most of his life in the town of Concord. His father was a Unitarian minister with a keen interest in fine literature who was instrumental in founding several important literary societies and publications of the time. When his father died, Emerson was given into the care of his aunt, who took a strong interest in his education. His literary gifts were recognized, encouraged and developed early. In 1817 he entered Harvard College where he met “Hindu missionaries,” including Raja Ram Mohan Roy. Emerson became licensed to preach in the Unitarian community in 1826. His early sermons contained the themes of his later famous essays. His early work from the pulpit also laid the foundation for his distinguished skill as a lecturer.

Grief over the death of his first wife drove him to question his beliefs and his profession in the Christian ministry, turning him to other religions for evidence of vital truth. He resigned from the Unitarian ministry and traveled abroad. Infatuated by the possibility of spiritual correspondence between man and nature, he began lecturing and writing. Personal experience played heavily into Emerson’s assimilation and expression of creative ideas. His disenchantment with Christianity finds its way into Compensation, one of his early essays. “Ever since I was a boy,” he writes, “I have wished to write a discourse on compensation; for it seemed to me when very young that on this subject life was ahead of theology and the people knew more than the preachers taught. It seemed to me also that in it might be shown a ray of divinity, the present action of the soul of this world, clean from all vestige of tradition; and so the heart of man might be bathed by an inundation of eternal love, conversing with that which he knows was always and always must be, because it really is now. It appeared, moreover, that if this doctrine could be stated in terms with any resemblance to those bright instructions in which this truth is sometimes revealed to us, it would be a star in many dark hours and crooked passages in our journey, that would not suffer us to lose our way.”

A man of considerable influence

Ralph Waldo Emerson was a poet, an essayist and a lecturer. He is considered one of the most significant leaders of the American Renaissance, which flourished at the middle of the nineteenth century. Besides Thoreau and Whitman, that period also featured the masterful work of other literary greats like Emerson’s dear friends Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Emily Dickinson. Collectively these notable artists had a profound effect upon the religious, aesthetic, philosophical and ethical thinking of the day, and Emerson was at the center of it all.

His transcendentalism left the literary world with a sense that there are mystic realities over, above and greater than the trials and tribulations of common, everyday life. Ironically, though, his writings were never without a measure of realistic pragmatism. He combined ancient classical humanism with Oriental metaphysics to ratify his own down-to-earth brand of philosophical monism.

“There is one mind common to all individual men. Every man is an inlet to the same. He that is once admitted to the right of reason is made a free man in the whole estate. What Plato has thought, he may think; what a saint has felt, he may feel; what at any time has befallen any man, he can understand. Who hath access to this universal mind is a party to all that is or can be done. How easily these old worships of Moses, of Zoroaster, of Manu, of Socrates, domesticate themselves in the mind. I cannot find any antiquity in them; they are mine as much as theirs.”

ARCHIVE PHOTOS

HENRY DAVID THOREAU, THE RECLUSE

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) made a few important ideas famous—but not during his lifetime. He said that man must follow his conscience regardless of cost, that life should be lived with awareness and appreciation and that the world of nature was superior to the world of man. Although these are not original ideas, his lucid, provocative writing made them convincing.

On first impression, Thoreau’s life was one of poverty and failure. He was a rebel. With prickly independence, he referred to his most famous work, Walden, as his “cockcrow to the world.” Toward the end of his life the fiery disdain of his youth died to warm embers. Because of his outspoken ways, he received few accolades for his literary accomplishments. Even his close friend Emerson predicted no literary greatness for him. Such evaluation humbled the talented writer as he got older.

An intensely practical man, Thoreau rarely idealized. Yet, of Hinduism he wrote in his journal: “What extracts from the Vedas I have read fall on me like light of a higher and purer luminary, which describes a loftier course through a purer stratum, free from particulars, simple, universal.”

Thoreau was austere and remained an ascetic throughout his life. This attitude was inspired by his encounter with the yoga of Hinduism. “Depend upon it that, rude and careless as I am, I would fain practice the yoga faithfully,” he writes. “The yogi, absorbed in contemplation, contributes in his degree to creation. To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a yogi.”

Mahatma Gandhi, another nonconformist, was deeply inspired by Thoreau: “My first introduction to Thoreau’s writings was when I was in the thick of the passive resistance struggle. A friend sent me his essay, Civil Disobedience. It left a deep impression upon me. The essay seemed to be so convincing and truthful that I felt the need of knowing more of Thoreau, and I came across his Walden and other essays, all of which I read with great pleasure and equal profit.”

The Legacy

According to historical accounts, Emerson was a quiet, humble and unassuming gentleman. Nevertheless, history also shows that he had a commanding and wide-ranging influence upon the humanity of his day. Thus, like many men of legendary greatness, he became more than the sum of his various identities as speaker, poet, writer and philosopher. Because the common denominator in and through all of his work was meditative introspection, he is recognized, loved and admired today as one of America’s first truly indigenous sages.

Searching the world over for glimmerings of truth and in the process delving deep within himself, Emerson discovered in the limitations of human comprehension what was perhaps his greatest find: humility.

“The philosophy of six thousand years (Hinduism) has not searched the chambers and magazines of the soul,” he lamented. “In its experiments there has always remained, in the last analysis, a residuum it could not resolve. Man is a stream whose source is hidden. I am constrained every moment to acknowledge a higher origin for events than the will I call mine.”

When the Earth’s most comprehensive philosophical system yielded what he considered to be, at best, a spiritual dilemma, Emerson was forced to seek his answers—as all mystics must—in personal transcendental experience. It should come as no great surprise that he would be fundamentally responsible for founding a movement referred to as Transcendentalism. As Emerson and the Transcendentalists became enamored with Hinduism, they took up the crusade of literary eclecticism, showing a breadth of vision that went beyond their heritage of European and American literature and thought. It was their dream to integrate Judeo-Christian and Americo-European transcendental thought with Hindu ideas. The result of that endeavor forms a good portion of the extensive appeal their writings still today all over the world.

“In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat-Gita, since whose composition years of the Gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial,” writes Thoreau. “And I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions.”

ARCHIVE PHOTOS

WALT WHITMAN, THE MYSTIC

Walt Whitman (1819-1892) was born in Long Island, New York. Having left school at the age of eleven, he was mostly self-educated. He worked as a typesetter, journeyman printer, school teacher, editor, stationer, journalist, essayist—and finally a poet.

Whitman lived in New York for 36 years. Around age 30, he experienced a spontaneous mystical illumination which was strongly reflected in his poetry. In Song of Myself, he writes, “All truths wait in all things. They neither hasten their own delivery nor resist it. The insignificant is as big to me as any.”

In 1855 he wrote Leaves of Grass, his most famous work, which he revised and published nine times throughout the remainder of his lifetime. Although the radical form and content of this poetry eventually marked him as a revolutionary epitome of American literature, he was, during his life, known more for his influence as a prophet of democracy and “an enthusiast of the common man.” The Transcendentalists loved him from the start and gave his work credence, for he exemplified their coveted denial of conformity in pursuit of individual mystical experience.

Whitman’s work was applauded first by great Eastern minds. Sri Aurobindo had respect for him and extolled him in his essay, Future Poetry. Tagore admired him and even translated one of his poems. Swami Vivekananda paid tribute to him as a “spiritual genius.” In the late 1860s Whitman received overdue recognition in America as the early reactions to his radical style began to fade. In 1870 Whitman wrote Passage to India. This poem moved beyond America, beyond humanity, to death and “the hereafter.”

In January, 1873, Whitman had his first stroke, which left him partially paralyzed. Shortly thereafter, he moved to Camden, New Jersey, where he spent the last years of his life. Facing his final days, he wrote Proudly the Flood Comes In, a wondrous contemplation of death. He died March 26, 1892.