By M.P. MOHANTY

India found itself in the unwelcome focus of world attention when in late December churches were attacked and burned in Gujarat State. Then on February 22, a Hindu mob attacked a church in Orissa and burned alive Australian missionary Graham Staines and his two sons. In this multi-part analysis of these alarming developments and complex issues, we begin with the first-hand report of our Delhi correspondent sent to Orissa to assess the situation.

By M.P. Mohanty, New Delhi

I was shocked to see the charred vehicles in which three human beings were burned alive a few days before. An atmosphere of gloom and shock hovered over this tribal village even seven days after the incident, when I first reached the remote place. The police had set up a temporary post and were busy in investigation. It took nearly nine hours for the first police to arrive at the scene, so distant is Manoharpur. The simple villagers were shocked to see for the first time in their life so many vehicles, each bringing in another VIP–minister, senior official, journalist, investigator, etc. The heavy police presence intimidated them. Seven local villagers were among the 49 arrested.

Coming in the wake of a spate of attacks on Christians on the matter of religious conversion in Gujarat and elsewhere in the country, the burning alive of missionary Graham Staines with his two young children, Philip and Timothy, shocked Indian society. “A monumental aberration,” stated the President of India, Shri K. R. Narayanan. Politicians of all color, social activists and common people condemned the ghastly act. Staines, an Australian by birth, had been working in the area for over three decades, running a leprosy home at Baripada along with other social projects. He came to Orissa in 1965 and knew the local languages.

Manoharpur is in the Keonjhar district of Orissa. It is a difficult 46-kilometer trek through dense forest from Anadpur, the nearest rail station. There is no drinking water, food or staying arrangements. During 50 years of independence, the village has remained as backward as before. There is no school, hospital, health center, community hall… nothing. It is in such neglected backwaters of the Indian tribal areas that missionaries such as Staines were welcomed.

I tried to speak to villagers about the incident. Even though I, too, am a native of this state, Orissa, I found most avoided responding out of fear. But a few did share their experiences. Mrs. Phool Besra of Manohar Pur, whose house lies next to the church, witnessed the incident along with other members of her family. “Such a bad thing, terrible thing, happened,” she said. “Sahib, [Mr. Staines] comes here every year. This time they came on Thursday. They show films on Jesus. We were all sleeping in the open air. Suddenly we heard voices, so many people were shouting. It must have been around midnight. They were around 50 in number. I did not know any of them. They warned us, ‘Anyone daring to come out will be murdered.’ They broke the glasses of the vehicles, then set them on fire. Not less than 250 Christians were sleeping in the church. Nobody came to the rescue. Scared for our lives, we could not do anything. The crowd did not attack anybody else. They shouted, ‘Jai Bajrang Bali’ [‘victory to Lord Bajrang Bali’–a battle cry], blew a whistle and left.”

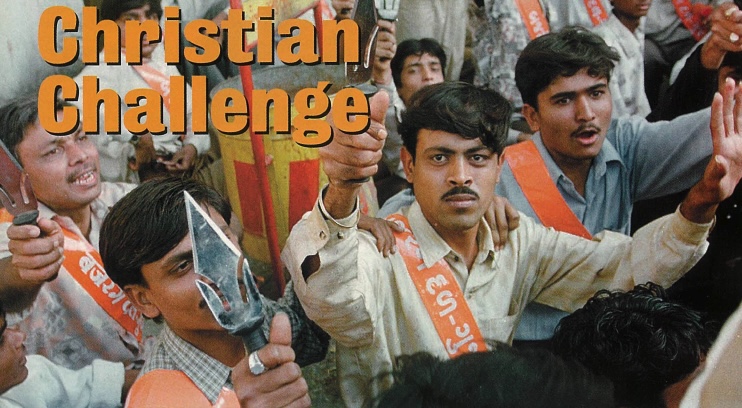

The administration and many people hold the Bajrang Dal, a militant arm of the Sangh Parivar, responsible. They deny involvement. The “Sangh Parivar” is a group of organizations with loose connections to the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS). It includes the BJP political party now ruling India, the VHP Hindu activist group, the Bhartiya Mazdoor Sangh labor union, Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram and others, according to long-time RSS member Sri Pran Nath of Delhi.

As with other recent attacks against Christians in India, early newspaper reports called the incident the work of “outsiders” and did not report any preceding local disputes. But Giridhar Mahant, former village chief (sarpanch) of neighboring Gayal Munda, told me, “Tension among the tribals was there earlier. During Raja [a famous Orissa festival], the Hindus and the tribals do not plow the land. It is a religious as well as social custom. But the Christian tribals break this tradition and plow their lands during the festival. Since 1983, the local police had to camp here during Raja to prevent conflict.” Giridhar continued, “Similarly, the tribals perform Asadhi Puja during the month of July. They worship the village Deity and offer goats, hens, etc. This is done by mass voluntary contributions. Before conversion, all the tribals contributed, but then those who converted to Christianity stopped participating in it. This angered the rest of the tribals. I condemn the killings, but you have to go deep into the matter to understand why such a thing happened.”

Thakur Das Murmu, the local sarpanch, mentioned nothing of the past. “It is the nasty work of some outsiders,” he said. “I am shocked. This should not have happened. I blame the government for this. No developmental work has been done in this area.”

One of the few local Christians who would speak with me was Samson, 30. His father is Dasnath Marandi, a tribal Hindu. He described the yearly “Jungle Camp” conducted by Staines, as a form of “friendship evangelism” in which each Christian who attends invites a non-Christian friend. “At 6 am we get up,” he explained. ” At 9 am we have bible class until 11 am, followed by lunch. At 2 pm we have bible class up to 4 pm. At 6 pm we watch films on Lord Jesus, his life, teachings, etc. For the last 20 years, it is regularly held in the month of January.” He was inside the church when the attack occurred and said the mob prevented anyone from getting out of the building.

Manoharpur is a tribal village, mostly of Hindu origin. It was 100 percent non-Christian in 1980. In 1986 one family was converted. As a result of Staines’ camps, the number has reached thirty.

I also went to Baripada, in the district of Mayurbhanj, to the Staines’ single-story home next to the Baptist Union Church. There was a heavy police presence. I met Mrs. Staines, but she very politely refused to give an interview, as it was just one day after her husband and children’s funeral. Her brother, John Weatherhead, had come from Canada. He told me, “My sister is staying on, and the good work will continue by her.”

Miss Mamata Das of Baripada, a Baptist and family friend of Staines, extolled the missionary. “He was one of the finest human beings. He knew Oriya language as well as Santhali and Ho [both tribal dialects]. He translated the Bible into Santhali. He ran the leprosy home with a lot of dedication. Staines led a very simple life. Yesterday 10,000 people joined his funeral procession.”

Now, many weeks after the incident, most of the key questions remain unanswered. The police are unsure who did it, and the main accused, Daran Singh, remains at large. Nearly all of those initially arrested have been released for lack of evidence. The local district magistrate has stated the Bajrang Dal has no local presence, though they were widely blamed for the incident. The area is extremely remote. It is not possible for outsiders to even find such a place in the middle of the night, much less to then escape. Necessarily, local people were involved.

The question remained in the minds of onlookers, if Staines was involved in social work only, why was he conducting Jungle Camps for the promotion of Christianity? A major state probe has been launched to answer these questions. The process of conversion and modernization has directly affected and threatened the age-old tribal culture, tradition and religion. The simple, yet determined, tribals are not pleased about it.

There are many obstacles to dealing intelligently with the recent Hindu-Christian clashes in India. Four major problems obscure the issues: 1) Media reports, especially in the English-language Indian press, are mostly unhelpful editorial rhetoric; there are few factual reports. 2) Initial stories on several Hindu-Christian clashes were inaccurate, and not corrected in future reports. 3) The national and international media attached far more importance to the tragic murder of Staines than to equally ghastly murders of Hindus during religious violence elsewhere in the country at the same time. 4) Hindus do not understand the missionary motivation and agenda.

The Media Bias: Hinduism Today received hundreds of media reports on the December through February clashes between Hindus and Christians. The vast majority consisted of public statements by politicians and editorial commentary; a rare few provided factual accounts of incidents. The best was that of a local Gandhian leader [see page 18] who in the process condemned the media’s “telephone journalism;” a shallow reporting that makes it is very difficult for Indians to form a clear picture of happenings.

The press bias is easy to discern: blame is cast upon the ruling BJP party, the RSS and the VHP, and the incidents are characterized as part of a coordinated nationwide campaign by the Sangh Parivar. By blaming the “Sangh Parivar,” the press disregards the root cause: missionary activity and resulting social disintegration. They fail to recognize or give credence to the very real desperation that is motivating individual Hindu communities to stop the missionaries’ destruction of their traditions.

Sloppy Reporting: In cases where further investigation was undertaken, it was often found that either 1) the report was inaccurate in characterizing the incident as a religious clash or 2) that tensions had simmered for some time and finally boiled over. In the latter cases the reasons were always the same: converts’ refusing to participate in ancient festivals, pressuring relatives to convert, insulting Hinduism and damaging icons or temples–tactics taught to converts by missionaries.

Take, for instance, the Rajkot “bible burning,” in which Hindus attacked a missionary school and torched hundreds of bibles. The incident was portrayed in the media as unprovoked desecration. But there was clear provocation. As Haren Pandya, Home Minister for Gujarat State, reported to the State Assembly, the school’s minor girls were being forced to make “a signed commitment on the last page of the bible which said they considered Jesus Christ as their savior.” He called this “a constitutionally illegal undertaking.”

One of the most scandalous incidents of 1998 was the rape of four Christian nuns in Jhabua, initially reported as religious terrorism by Hindus. But journalist François Gautier, of Le Figaro, France’s largest circulation newspaper, visited Jhabua and reported, “The nuns themselves admitted it had nothing to do with religion,” as their attackers were both Christians and Hindus.

Then there are the claims of “atrocities” and massive damage in Gujarat’s Dangs district. For all of the “dozens of incidents” that continue to be cited by Christians and others, the actual damage for all the buildings was just Rs. 400,000 (us$10,000), and no one was killed.

Discrimination: Gautier points out the incongruity of the strident outcry in the Indian press over the Staines murders. “Is the life of a Christian more sacred than the lives of many Hindus?” he challenged in an article published in the Hindustan Times. “It would seem so, because not long ago in Punjab or Kashmir militants would stop buses and kill all the Hindus–men, women and children–not in one incident, but many times over several years. But there never was such an outrage as provoked by the Staines murders.” Consider, for example, the incident in Kashmir [sidebar, page 23] in which a Hindu family of four, including a small child, were killed by Muslim terrorists seeking to frighten Hindus into leaving the village of Sukcha. In a prominent Indian newspaper based in the US, the murders warranted an 11-line report on page 23. In the same issue is a front-page story of a march by Indian Christians protesting “attacks against their brethren in India.” In like manner, the Christian bias found its way into the Western media.

Another demonstration supporting Gautier’s position on the one-sidedness of the national and international press was a petrol-bomb attack on a Hindu temple in Melbourne, Australia, on March 11, possibly in retaliation for the Staines murder. Earlier the same day an Australian Christian politician demanded that India protect its Christians and “put an end to communal violence.” But the attack was “non-news,” rating only a short item in the local newspaper, even though the priest and his family barely escaped, and the police investigated the bombing as attempted murder. The property damage was ten times greater than in all the clashes in Dangs. Despite press releases sent out internationally by Hinduism Today on the incident, there has been little reaction. The Australian press complained loudly when Christians in India were harmed, but ignored a potentially deadly attack on local Hindus.

Religious violence is occurring all over the world, not just in India. In the US, dozens of African-American churches have been destroyed in recent years by arsonists. The motivation is no secret, as one group of perpetrators said at their trial: “to strike at the spirit and the soul of the Black community.”

Hindus can alleviate anti-Hindu bias, especially in the English-language press, by demanding greater accountability. Inaccurate reports can be corrected by media watchdogs, and accurate information provided when it is missing. All concerned Hindus can help by writing to newspapers and magazines and insisting on accurate and factual reporting on sensitive issues.

Missionary Motives: Why are Christian evangelists stationed among nearly every hill tribe across India, and in the remote areas of many other countries? The answer to this key question lies in Christian strategy.

Evangelists devoutly seek to fulfill the “Great Commission,” as is stated in Matthew 24:14: “This gospel of the Kingdom of God shall be preached in all the world for a witness unto all nations; and then shall the end come.” Harold Lindsell, former editor of Christianity Today and co-founder of Fuller Theological Seminary, explained the missionary thinking in his essay, “Fundamentals for a Philosophy of the Christian Mission,” in the book The Theology of the Christian Mission. Summarizing the “conservative mission theology,” he writes, “The obvious fact that Christ has not come indicates that the Great Commission has not been fulfilled as yet. When it has been fulfilled, Christ will come again.” In other words, preaching the gospel to the world will bring the return of Christ.

The global plan to achieve this–now available on Evangelical web sites [see page 17]–is to put missionaries in every “nation,” (defined as a “people group” with a specific language and culture). India has the largest number of “people groups” yet to hear the gospel. It is, in fact, a main target of evangelists anxious to fulfill the Great Commission, have Christ return, and–according to the Jehovah Witnesses and some other Pentecostals–be among the 144,000 souls who go to heaven.

The web sites we visited barely mention social service as an objective, in contrast to the position taken by the missionaries funded by these organizations in India. Lindsell states, “The humanitarian aspect of medicine and education is not considered to be a proper reason for their use. It is an incidental byproduct of means which have for their primary objective the conversion of men.”

Christians speak openly of their mission in terms of “spiritual conflict.” The “Lausanne Covenant” is a statement of the huge 1974 International Congress on World Evangelization, encompassing most of the missionary-sending churches (see full text at www.ad2000.org/handbook/lcwe.htm). The Covenant states, “We believe that we are engaged in constant spiritual warfare,” “with the principalities and powers of evil [the forces of Satan], who are seeking to overthrow the Church and frustrate its task of world evangelization.” The text continues in military terms: “God’s armor,” “battle,” “weapons,” etc. Such obstacles as a tribal’s worship of Hanuman, are believed the work of the very devil himself, to be suppressed aggressively by any means. Here is found no attitude that would go far in improving community relations. To convert a person requires first destroying his existing religious beliefs, even those that are tens of thousands of years old.

But conversion is a flawed undertaking. In missionary activity, much damage is done to the faith of many with the gain of only a few converts. The effort threatens to destroy myriad cultures, as it has done in the past on massive scales in the Americas, in Europe, Africa, etc. (see reports on pages 19 and 25). India is, in fact, one of the few nations in the world that has retained its indigenous faith and not been converted to Christianity, Islam or communistic atheism.

The government of India keeps track of the funds sent into the country for Christian organizations, but the numbers are not readily available. The latest figure we found was for our 1989 report on evangelism in India. At that time, the government said us$165 million was coming into India each year, this from a yearly worldwide mission budget of $1 billion for all churches combined. The numbers today are probably much higher.

What can Hindus do about the missionary threat? On the governmental level, it is first a matter of enforcing existing laws. For example, had those who desecrated the Hanuman statues in Dangs been arrested for their crimes, the subsequent attacks by fed-up Hindus may not have occurred. India stopped issuing visas long ago to foreign missionaries (as have many other countries including Singapore and Japan and nearly all Muslim countries), and can expel those found to engage in illegal activity. The government can continue to release the figures of foreign contributions, which allows the average Hindu to better understand the situation. India has stringent laws against denigration of another’s religion, and these, too, can be uniformly enforced. It is not a violation of religious freedom to enforce laws that apply to everyone equally. The economic exploitation of tribal Hindus can be alleviated on a government level, so that villagers are not tempted into conversion by hopes they will gain economically.

The late Ram Swarup, one of India’s great thinkers this century, said, “If one truly understands Hinduism, he would never feel a need to convert from it, for Hinduism is the whole, other religions a part. Everything can be found within Hinduism itself. Hindus should become aware of the forces of conversion. We need not panic, but we cannot afford to be indifferent. In these difficult times, our greatest strength lies in our innate spirituality. We should recover our confidence and self-identity.”

Swarup’s cogent analysis highlights the need for religious education on every level of Hindu society. It means, too, that Hindu leaders should actively study the missionary movement, log onto their web sites, read their literature, get on their mailing lists in the West, follow their activities and respond accordingly with positive programs.

All responses to the missionary programs must embody the Hindu ethic of ahimsa–nonviolence in thought, word and deed. Challenges by other religions–even attempts to destroy thousands of years of tradition–do not provide justification to deviate from the lofty principles of our own. Hinduism survived the Muslims, it survived the British, and it will survive this, too

OH, WHAT A TANGLED WEB WE WEAVE…

Claims of a global Christian plan for conversion are routinely met with skepticism by the Indian press. For example, in the Indian Express report of February 7, 1999, on VHP activities in the northeastern states of India, sarcastic reference is made to a priest “who is convinced that Christians the world over have a devious agenda in Arunachal–maybe even a pan-Indian agenda.” Anyone caring to investigate can visit a cybercafe and log onto http://www.bethany. com/profiles/c_code/india.html to study detailed conversion plans for not only Arunachal Pradesh, but all of India.

At the Bethany site, India is divided with scientific precision into 186 individual “people groups.” A long description is followed by advice on how to convert each to Christianity. For example, under the Hindi-speaking “people,” it is stated, “They must first be set free from bondage to millions of false gods so that they can put their trust in Jesus. Six mission agencies are currently working among them.” After each such description, a list of “Prayer Points” is given. Typical is the following: “Pray against the spirits of Hinduism that are keeping the Munda-Santal [of Bihar] in spiritual darkness.”

Or visit the Native Missionary Movement of India at www.nmmindia.org/. Their mission statement: “Our top priority is fulfilling the ‘Great Commission’ [to bring the Christian gospel to every people in the world]. We concentrate on the most unreached nucleus of people in the world–India. Our vision is to train and support 1,000 native missionaries in North India and plant 300 new local churches.” They quote a missionary characterizing a village: “Here the demonic forces are so real.” Or visit www.ad2000.org/utermost.

htm to read that North India is “strategically important in completing the unfinished task of world evangelization.”

Notably absent from these sites is “social service” as an aim in India–contrary to missionaries’ claim. The real goal is conversion of men, which means the destruction of Hinduism.