Plants provide our food, clothes, medicine, building materials and the oxygen we breath, yet we seldom honor their import. Perhaps more than any faith, Hindus have mapped the divine nature of the plant world. Our Insight Section this month explores two preeminent botanicals: Tulsi and rudraksha . . .

Few human cultures value and venerate the millions of species of plants upon which our lives, and our enjoyment of living, so profoundly depend. The tribals are an exception. In Brazil today medicine men know every forest botanical intimately, and plainly claim they talk to plants and plants teach them much. America’s Indians still esteem plants and know the interrelationships we share with our photosynthesizing kin. But for sheer depth of detail and ritualistic reverence, few cultures can parallel the intricate and profound relationships between the human and botanical kingdoms found within the Sanatana Dharma. Virtually every species has a purpose and a pious place. Among the elite must be counted rudraksha and tulsi, loved by worshipers of Siva and Vishnu, respectively. The rudraksha is a towering tree yielding an intricate, carnelian seed. Tulsi is an unassuming, bushy herb. Both are found in temple, home, roadside shrines and on the bodies of the devout, who wear them for healthful benefits and to please the Gods. Non-Hindu aspirants seek out both to aid their spiritual quest. Now a look at two remarkable plants and their unique place in the lives of hundreds of millions.

Tulsi: the Holy Basil

Tulsi, Ocimum sanctum, belongs to the family of Labiatae. The classical name, basilicum, from which “basil” is derived, means “royal or princely.” Hindus know the plant as Tulasi and Surasah in Sanskrit, and Tulsi in Hindi. Other commonly used names are Haripriya, dear to Vishnu, and Bhutagni, destroyer of demons. Tulsi is an upright, many branched, softly hairy annual herb ranging in height from 30-60 cm. Its leaves are slightly smaller and paler green than the common basil. All Ocimum species are similar, but Vaishnava Hindus intransigently attest that there is only one true Tulsi–Ocimum sanctum.

What distinguishes Tulsi from other basils is its peerless religious significance. Tulsi is Divinity. It is regarded not merely as a utilitarian God-send, as most sacred plants are viewed to be, but as an incarnation of the Goddess Herself. Thus, when one bows before Tulsi, one bows before the Goddess. Of course, denominations differ in their approach. Generally, worshipers of Vishnu will envision Tulsi as Lakshmi or Vrinda; devotees of Rama may view Tulsi as Sita; while Krishna bhaktas revere Her as Vrinda, Radha or Rukmani.

A plethora of Puranic legends and village stories relate how Tulsi came to grow and be worshiped on Earth. The classic Hindu myth, Samudramathana, the “Churning of the Cosmic Ocean,” explains that Vishnu spawned Tulsi from the turbulent seas as a vital aid for all mankind. More common are legends that describe how the Goddess Herself came to reside on Earth as Tulsi. A complex legend in Orissa views the plant as the fourth incarnation of the Goddess who appeared as Tulsi at the beginning of our present age, the Kali yuga. The tale continues with intrigue and deception among the Gods, typical of the Puranic stories, culminating in Vishnu’s transforming the Goddess Tulsi into a basil bush to be worshiped morning and evening by men and women in every household in the world.

Traditional worship begins when seeds are sown on the eleventh day of the waxing moon in the month of Jyestha, May-June. The plant is then nurtured for three months. The worship during this period is simply the loving care offered the tender seedling. Beginning on the full-moon day of Ashvini, September-October, the worship intensifies with prayers and chanting, circumambulation of Tulsi seven times each morning, offering of camphor or oil lamps once or twice a day and offering of water, rice, flowers and sweets, especially by the women of the household. Worship culminates on the eleventh day of the waxing moon in Kartika, October-November, in a festival called Tulsivivaha, when the Goddess Tulsi is ceremoniously wed to Her consort, Lord Vishnu. Vishnu is represented at this wedding by His sacred symbol, the saligrama, a black ammonite stone from the Kali Gandaki river of Nepal. The most devout conclude the worship on the following 14th day by offering leaves one by one to a river or sacred tank while chanting the Vishnu Sahasranama, the Lord’s 1,008 names.

The woody stem, branches and seeds of Tulsi lend themselves well to fashioning into simple beads, and industrious devotees create malas, rosaries, with beads made from the plant (now dead) that they had just nurtured, worshiped and wed. These malas are used for japa, prayerful chanting, and worn to insure blessings and protection of the Deity throughout the year. If not made into beads, the dried Tulsi plant should be discarded only in a river, ocean or pond.

Tusli, along with all other species of basil, possesses remarkable physical and spiritually healing properties, as author Stephen P. Huyler summarizes, “Aside from its religious merits, Tulsi has been praised in Indian scriptures and lore since the time of the early Vedas as an herb that cures blood and skin diseases. Ancient treatises extol it as an antidote for poisons, a curative for kidney disease and arthritis, a preventative for mosquito and insect bites, and a purifier of polluted air. Generally prepared in medicinal teas and poultices, Tulsi’s widespread contemporary use in India as an aid to internal and external organs suggests these traditions are based upon practical efficacy.” One finds descriptions of basil’s health benefits in any of the books on herbs and ayurveda readily available today.

Tulsi is also extensively used to maintain ritual purity, to purify if polluted and to ward off evil. A leaf is kept in the mouth of the dying to insure passage to heavenly realms. During an eclipse, leaves are ingested and also placed in cooked food and stored water to ward off psychic pollution. Funeral pyres often contain tulsi wood to protect the spirit of the dead–as Bhutagni, destroyer of demons. tulsi leaves and sprigs are hung in the entryways of homes to keep away troublesome spirits, and the mere presence of the Tulsi shrine is said to keep the entire home pure, peaceful and harmonious.

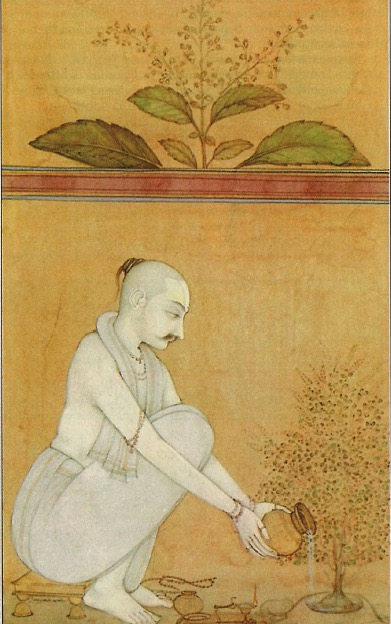

Perfect picture of devotion: The following episode was written by Huyler as he witnessed Tulsi worship in an Orissan home. It conveys the intimate relationship the Hindu has with Tulsi, and it teaches, through exquisite example, how we may worship Her.

“‘O Tulsi, you who are beloved of Vishnu, You who fulfill the wishes of the devout, I will bathe You. You are the Mother of the World. Give me the blessings of Vishnu.’ The high, cracked voice of Manjula pierces the damp predawn hush. Joining her voice, other women also sing the praises of the Goddess. They all kneel before a meter-high terracotta planter shaped like a miniature temple adorned with sculptures, and containing a green-leafed Tulsi [photo, page 32]. Rising to her feet, Manjula pours holy water from a small, brightly polished brass pot into the cupped palm of her right hand and sprinkles it upon the leaves of the bush. Her expression is one of adoration but also one that portrays many years of close association, of friendship. For Manjula, the Goddess is incarnate in this herb, representing the duty and dedication, the love, virtue and sorrow of all women. She is a link to Manjula’s own soul.

“Manjula’s actions are repeated by the other women. Beneath their feet are designs of flowers and conch shells painted directly onto the ground with white rice powder and sindur (vermilion). Placing the brass pot on the ground amid the paintings, Manjula lights camphor incense in a clay pot and waves the clouds of sweet smoke over and around the bush and its container. Holding a clay lamp filled with lighted ghee in her right hand, she rotates it in a large circle three times in front of the tulsi plant. Bowls of fruit (bananas, apples, guavas and the meat of dried coconuts) and hibiscus and marigold flowers are placed on the ground before the terracotta.

“Incense sticks are lit as Manjula once again presses her hands together in reverence, singing: ‘O Tulsi! Within your roots are all the sacred places of the world. And inside your stem live all the Gods and Goddesses. Your leaves radiate every form of sacred fire. Let me take some of your leaves that I may be blessed.’ With her right hand clasped around the stem of the small bush, she shakes it gently, causing three leaves to flutter to its base. Thanking the Goddess, she places a single leaf between her palms and prostrates herself before the planter. After lying in this posture of absolute supplication for several minutes, Manjula again kneels before the Tulsi shrine and lovingly asks the Goddess if she may be allowed to dress Her. Taking a length of red cotton cloth from a basket, she wraps it around the bush. Then she places bright red hibiscus flowers in the upper leaves and hangs garlands of marigolds around the stem and the planter. Culminating the ceremony, Manjula puts the tulsi leaf in her mouth, taking into her body the spirit of the Goddess. Followed by the other women, she walks seven times around the elaborately sculpted planter, chanting: ‘O Goddess Tulsi, You who are the most precious of the Lord Almighty [Vishnu], who live according to His Divine Laws, I beseech you to protect the lives of my family and the spirits of those who have died. Hear me, O Goddess!’

“As the first rays of the rising sun hit the tulsi’s top leaves, the ritual has ended. Every morning and every evening of the year, Manjula prays to Tulsi at the shrine on the doorstep of her house, but that worship is usually simple and straightforward, entailing sprinkling the bush with holy water, adorning it with a few hibiscus blossoms, and shaking down a few leaves to eat as part of her prayers. This morning’s elaborate ritual celebrates the first day of Kartika, a month particularly sacred to Vishnu and his Goddess-consort Tulsi. By caring for and honoring this sacred bush, Manjula creates a bond with the Goddess. Representing honor, virtue and steadfast loyalty, this humble bush of herbal leaves is the archetype of Hindu femininity, revered by men and emulated with empathy by women. She is Tulsi, Mother of the World.”1

Rudraksha: Tears of God

Rudraksha names both a sacred seed and the tree that bears it. In English, it is called the Blue Marble tree, or, less commonly, the Utrasum bead tree. It is known botanically by the names Elaeocarpus sphaericus, E. grandis and E. ganitrus. Throughout the world, there are 120 species of Elaeocarpus (elaeo means “oil,” and carpus, “fruit”), 25 of which are found in India. The tree has a remarkable range of habitation–from the Himalayan foothills, to Southeast Asia, Indoneasia and New Guinea, to Australia, Guam and even Hawaii. Production of rudraksha beads in India cannot keep up with demand, so a flourishing import trade has developed between India and Indonesia. It is intensively grown around a few villages on the islands of Java and Bali. Other important Indian species are E. floribundus, E. oblongus, E. petiolatus, E. serratus and E. tuberculatus. Although virtually every Hindu is familiar with the rudraksha bead, only a few have seen the tree.

The rudraksha is a medium-to-tall evergreen (E. grandis can grow up to 120 feet) with a spreading handsome crown. It grows quickly and bears fruit in three to five years. As the tree matures, the roots buttress–rising up narrowly near the trunk and radiating out along the surface of the ground–giving a gnarly and prehistoric appearance. Attractive, creamy white flowers give birth to green fruits one-inch in diameter, which turn purple and brilliant blue when ripe [see inside front cover]. The white wood has a unique strength-to-weight ratio, making it a highly valued timber. During World War I, it was used to make airplane propellors. The splendor of the tree, however, is its intricately ornamented fruit stone which, when arduously cleaned, becomes the ruddy and revered rudraksha bead.

All legends of the origin of rudraksha describe them as the tears shed by Lord Siva for the benefit of humanity. “Rudra” stems from the Sanskrit rud or rodana, which means “to cry.” It is the original name for Siva as it appears in the Rig Veda. Aksha means “eye,” and thus rudraksha beads are deemed the tears of Siva. Though accounts vary as to exactly what stirred Siva to shed His historical tears, the most common legend describes how He wept out of compassion as He beheld the effrontery of mankind. Naveen Patnaik briefly tells the tale in The Garden of Life, “Rudra wept when He witnessed the towering metropolis, Tripura, or triple city, created by man’s superbly ambitious technology. In its arrogance, this magnificent human creation had undermined the balance between the Earth, atmosphere and sky. Then, according to the Mahabharata, having shed the implacable tear which turned into a rudraksha bead, ‘The Lord of the Universe drew his bow and unleashed his arrows at the triple city, burning its demons and hurling them into the western ocean, for the welfare of creation.’ ” Wearing the rudraksha, devotees remind themselves of God’s compassion for the human predicament, His watchful love for us all.

Along with vibhuti (holy ash) and the trishula (trident), rudrakshas are among the quintessential regalia of Saivism. Nevertheless, the Padma Purana states that rudrakshas may be used by Hindus of every denomination. They will even benefit atheists and sinners. Rudraksha beads are not objects of worship. Rather, they are used as worshipful aids and accoutrement. Primarily, the beads are strung into strands and worn on the body. These malas are also used in the practice of japa.

Facets of benevolence: Scriptures describe four main categories of rudraksha according to colors white, red, yellow and black. Different species are said to bear different colored seeds. Today, however, it is rare to find any color but red. Beads range in size from .25 to 2 cm. Though the Meru Tantra declares, “Of rudraksha and Sivalinga, the bigger they are, the more powerful,” small ones are more highly valued, possibly due to their rarity or the ease of wearing and carrying them. Chandrajnana Agama describes other characteristics in verses 13-14: “Rudrakshas the color of copper are sublime. Those that are hard, big and highly ornamented are considered virtuous. Those eaten by worms, broken, without detail, full of wounds and unshapely are forbidden.” Such inauspicious beads are called bhadraksha.

A rudraksha is categorized primarily by the number of its “faces.” Longitudinal grooves begin at the pedicellar end and go all the way to the basal end of the bead, dividing it into cells which encase the seeds. In Sanskrit these are called mukhas, or faces. The classical designation describes 1-14 faces. Other sources speak of 21, while a few list 30 or more. Most common by far is the five-faced bead, followed by the four- and six-faced. Rare variations are the Gowri-Shankar, a double-joined bead, and the Brahma-Vishnu-Mahesvara, a triple-joined bead. These are highly prized but rarely found, and fetch a high price. Single-faced rudrakshas are the most valuable and extremely rare. They are kept as family or spiritual heirlooms and are often encased in gold. Legend states that trees produce single-faced beads in sets of three. One disappears into the sky; one buries itself in the earth and one remains on the ground for a pious person to find. Two such single-faced rudrakshas are kept in the inner sanctum of Nepal’s Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu. One is shown to pilgrims at auspicious times through the year.

Many scriptures extol rudraksha. Some are dedicated solely to expounding its merits. The Rudraksha Jabalopanishad is the 88th of the 108 Upanishads and forms part of the Sama Veda. It describes in detail the nature of rudraksha, its variations, how to wear the beads and for what purpose. The properties of the beads are summarized as follows: One-faced, Siva: dissolves sins, removes obstacles to spiritual growth and bestows worldly desires. Two-faced, Siva-Parvati or Ardhanarisvara: for good living and enlightenment, beneficial for husband and wife. Three-faced: good for health, knowledge and wealth, especially helpful for the unlucky. Four-faced, Brahma: promotes supreme knowledge, happiness, prosperity and progeny; improves memory and speech. Five-faced, Pancha Brahman or Kalagni Rudra: bestows enlightenment, good luck and aids in achieving desires. Six-faced, Kartikkeya: good for education and business. Seven-faced: worn for wealth, flawless health, right perception and purity of mind. Eight-faced, Vinayaka: longevity, prosperity and truthfulness. Nine-faced, Durga: removes fear of death, increases happiness. Ten-faced: protects from miseries, gives success and neutralizes planetary afflictions. Eleven-faced, the eleven Rudras: brings victory in all encounters, enhances happiness and well being. Twelve-faced, Maha Vishnu or Surya: eliminates disease, increases happiness and wealth. Thirteen-faced: wish fulfilling, promotes fertility. Fourteen-faced (rare), Siva: freedom from disease, misery and ill feelings; bestows bhakti, love, honesty and intelligence.

To your heart’s content: Ayurvedic texts offer numerous references to rudraksha’s healing qualities, as Dr. A. Satyamangalam summarizes in an issue of The Kalyana Kalpataru, “The pulp of the fruit is a cure for mental illness and epilepsy. Powdered beads taken before breakfast cure the common cold. To reduce high blood pressure, drop four to ten five-faced beads in 50 grams of water and keep it overnight. Drink this water daily for two months. To insure an infant’s well being, rub a rudraksha bead on a clean stone with honey and place a drop of the paste on the infant’s tongue.” Both the fruit and the stone (bead) have long lists of healing properties. However, the easiest way to reap the benefits of rudraksha is to wear the beads. The mere touch of rudraksha is touted to regulate blood pressure, aid in the strengthening of the heart, absorb excess body heat, balance the physical energies and neutralize mental disorders. Scriptures elaborate how wearing rudraksha pleases the Gods and protects the soul by keeping troublesome spirits at bay and keeping the mind of man attuned to that of his beloved Deity.

1 SELECTION REPRINTED FROM GIFTS OF EARTH: TERRACOTTAS AND CLAY SCULPTURES OF INDIA BY STEPHEN P. HUYLER (AHMEDABAD: MAPIN PUBLISHING PVT, LTD, DISTRIBUTED IN THE USA BY THE UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS)

WHERE YOU CAN ACQUIRE QUALITY TULSI AND RUDRAKSHA:

NAVRATAN EMPORIUM, P.O. BOX 31, GAU GHAT CHOWK, PO HARDWAR 249 401, INDIA. POOJA INTERNATIONAL, 34159 FREMONT BOULEVARD, FREMONT, CALIFORNIA 94555; BAZAAR OF INDIA IMPORTS, 1810 UNIVERSITY AVENUE, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94703-1516; MEENA JEWELERS, 2643 WEST DEVON AVENUE, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60659; MONEESH, 467 BRICKMAN ROAD, HURLEYVILLE, NEW YORK 12747; TULSI SEED (FOR PLANTING ONLY): JOHNNY’S SELECTED SEEDS, FOSS HILL ROAD, ALBION, MAINE 04910-9731.