By VRINDAVANAM S. GOPALAKRISHNAN

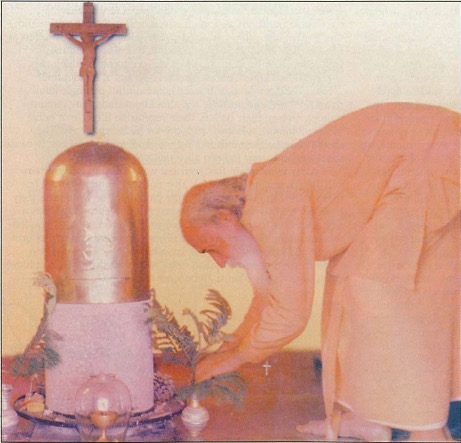

Peter Julia came to India from Spain in 1948 as a 23-year-old Jesuit priest. Today, at 71, he has taken the name Shilananda, built and operates a church in Nasik, Maharashtra, which resembles a Siva temple and is called Sanjivan, “True Life.” A small cross sits atop the tower. On the sanctum walls inside hangs another cross, and below that a stone Sivalinga [photo] covered with a metal sheath. An “Aum” and a cross are engraved in the brass. A second container shaped like a Sivalinga holds the consecrated hosts (bread wafers) used in the Catholic celebration of Mass. The Week magazine quotes Shilananda, “The power of life comes from God. Siva is the most ancient God of India, and the Sivalinga is a symbol of life-giving power. There is no contradiction in having a Christian temple. Christ gives a deeper meaning to what is here.” He says he has made no converts.

But some Hindus are perplexed and a few are downright incensed with this kind of amalgamation of religions. Mr. Pradeep Mohan, a Siva devotee, told Hinduism Today, “It is ridiculous and rather blasphemous to associate Lord Siva, the Supreme Lord, who had been worshiped even long before the birth of Jesus, with the bread of the Catholic Mass.” He added, “The Christians have lost ground in India, especially in Kerala, and all of their superficial tactics of global evangelization using the old methods have failed.”

Whatever one may think of missionaries in general, Shilananda no doubt lives an exemplary and austere life. He is a vegetarian, well-versed in Hindu scripture and devout in his daily practice. And there are more like him in India, sincere Christians attempting to create an indigenous form of a faith too Western for most Indians and too Indian for most Catholics.

One such place is the Saccidananda Ashram founded by two French priests in 1950. According to the inmates, it is a blending of Christian and Hindu monasticism and follows the customs of a Hindu ashram. Their church is built like a Hindu temple, with a high gopuram, and Hindu-like ceremonies are performed. The altar is on a raised stone platform where a silver statue of Jesus is placed. Sandalwood paste is given in the morning, kumkum after the midday prayer and holy ash after the evening prayer. Each prayer is accompanied by arati and chanting of the Gayatri Mantra. To the local people there doesn’t appear to be much difference between Hinduism and worshiping Jesus in the Hindu way. The priests claim to be teaching from the Bible, the Gita, the Puranas, Upanishads and the Koran.

Still another is Angelo Beneditt, who came to India from Spain with Shilananda in 1948. He is known to the villagers in Bhavanagar in the state of Gujarat as Swami Shubhananda. He immersed himself in the Hindu scriptures even before he was ordained a Jesuit priest in 1959. He is fluent in five European languages plus Marathi, Gujarati and Sanskrit, and has a BA in Indian classical music. He said, “I realized the cosmic nature of God from my contact with Hinduism. I find all religions manifestations of God.” According to him, there is no conflict between his abiding Christian faith and his belief in many Hindu principles. The church he established in his Tapovan Ashram is called a temple.

Such attempts at amalgamation are not new. In the 17th century Father Robert de Nobili learned Sanskrit, put on orange robes, became a vegetarian and wrote an apocryphal fifth Veda referring to Jesus. He converted tens of thousands in Madurai. Nearly all drifted back to Hinduism after his passing.

It’s a meditation on unintended consequences–a likely eventual long-term result of these missionaries’ continuous adoption of Hindu names, vestments, rituals, architecture and scriptures may be their own unwitting absorption into the all-embracing arms of Hinduism.