BY SWAMI SATYAMAYANANDA

No child understands violent methods, be he Indian, American or Chinese. A child undergoing traumatic experiences inevitably will carry those traumas into adulthood, where they will crystallize and cause endless troubles. All this has been studied and presented in hundreds of books on child psychology.

The relationship between a teacher and a student should be based on love, not the fear of violence. The teacher needs to have a clear identity as a teacher. His subject area must be clear to him and to his students. Imparting knowledge of any kind through the medium of love, understanding, patience and sacrifice will yield quick results.

Nobody owns anybody. To think otherwise is a mistake generally made by people, who then think they have a right over somebody. Each child should be understood as an individual, one whose psychological needs are unique to him and different from those of others. Each individual is a jiva, an individual soul, working out his karma. It is the students’ karma to be there studying, and it is the teacher’s karma to teach them. The idea is to perform good karma, which leads to purification of the mind. Performing bad karma leads to the opposite. Teaching and learning is an aspect of the path of karma yoga as explained by Swami Vivekananda.

The teacher must bring the idea of spirituality into his own personal life. He must believe and live the philosophy that God resides in each name and form and that all bodies are temples of God. The act of teaching then becomes one of worship. This is practical spirituality. It is only upon seeing a sattvic (pure) teacher that the students can and are willing to emulate or obey him. If you have love inside, it is automatically intuited by others, and they will love you in return. If you have dislike, immediately barriers come up in other’s minds. Then to reach out and communicate is impossible.

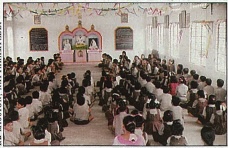

I advise teachers to take off all pressures and let the processes of teaching and learning be joyful. There is no teacher who does not feel he is learning while he is teaching. Learning and teaching are intimately connected with each other. Never blame the students if they fail to learn. Rather blame yourself for not trying adequately. Make the students understand the goal of the teaching, and grasp that the specific lessons are the means by which they can reach that goal. To effect transfer of knowledge, there should be an atmosphere of peace and serenity.

“Fine and good,” say some teachers, “but what am I to do with the unruly student? Isn’t the cane the quickest way to get his attention back on his studies?” At our Ramakrishna Mission schools, we have developed alternatives. They are based on the principle in the Bhagavad Gita, “Whatever a superior person does, another does that very thing!” Build your own life first, we believe. The great Swami Vivekananda said, “Be and make.” That is, be what you want the students to attain, then help them attain that.

Now, practically speaking, if an undisciplined student is not punished, then the students who are good and disciplined will suffer. They will see the others getting away with mischief and this will erode their faith in themselves and in the concept of discipline. So the good have to be rewarded and the undisciplined ones punished. How the teacher does it depends a great deal on his integrity, intelligence, and so forth. Punishment need not be hitting them. This defeats the purpose in the long run.

Young students need to be firmly dealt with, that is, given an unpleasant duty to perform, or have their privileges cut. Older boys need to be talked to in a calm manner and the error of their ways explained to them. Punishment should depend on the wrong done, as well as the mental make-up of the student. This is very important and until and unless the teacher has understood the psychology of the students, the punishment he gives might sometimes be too harsh or undeserved, and sometimes too light.

Make a student feel responsible for the wrong done. This sense of guilt should chastise them sufficiently. However, if it overly upsets the student, then quickly step in to set things right. At the same time, don’t be deceived by students’ play acting that they are remorseful when they are not. Everybody likes their sense of freedom. Curtailing it is found to be a very effective punishment. One can punish erring students by involving them in small duties of the institution; for instance, mowing the lawn for a week, washing the corridors, or stopping them from play, instead of physically punishing them by beating. In extreme cases, use the threat of expulsion or demotion. The teacher can segregate the undisciplined, keep a close tab on their work and make them feel ashamed. But don’t prolong it too much. The teacher must use his discrimination here, lest he discourage the students. Only scold somebody in front of his class if you know he needs it, but later call him and explain the issue again so he understands. Ordinarily it is better that the student be scolded in private.

Assign one among the students who is popular, to be a monitor. He can act as a formal or an informal link between the institution and his classmates. But see that no undue importance is given to him. Share his role by turns. He will prove useful in explaining issues of discipline to the students, as well as hearing feedback.

Finally, the teacher should endeavor to learn each student’s individual family background and circumstances. This is important in understanding him, for only when you understand the student can you help him attain what you are training him to be.