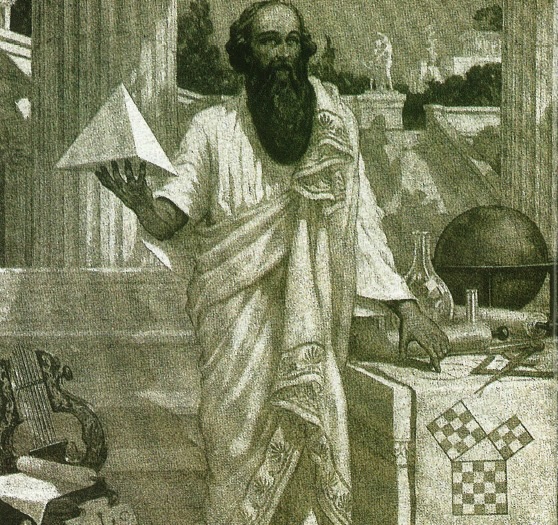

Pythagoras is generally accepted to be one of the most significant fountainheads of Western thought. Of particular interest to Hindus is the fact that his teachings were in tune with the thinking of the far East–especially India. In this article, Peter Westbrook, a writer and lecturer on music and cosmology, amplifies these connections. He is co-author with John Strohmeter of “Divine Harmony,” a book that recounts the fascinating story of the life and teachings of this legendary man.

Many centuries ago there lived a great teacher who was part of an ancient guru paramparaâ a tradition. For nearly forty years he traveled extensively and studied at the feet of many masters. Eventually he founded a community centered on an ashram where he recommended a contemplative, vegetarian lifestyle, taught the doctrine of reincarnation and trained his followers in sacred knowledge aimed at uniting the human soul with the Divine. His biographers attribute miraculous abilities to him, not the least of which was the ability to mentally perceive the deepest structures of cosmic life.

Hinduism Today readers might well assume that these events took place in India and describe the life of a Vedic rishi or Hindu sage. But, in fact, the man in question came from Greece and was one of the founders of the Western tradition. His name was Pythagoras of Samos.

A Man of Many Talents

In the modern world Pythagoras is best remembered for the mathematical theorem that he is said to have created–the one about the square on the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle. But Pythagoras was responsible for much more; he played a pivotal role in transmitting knowledge from the wisdom of ancient traditions into the modern world. At the same time, he stands at the fountainhead of our culture. The ideas he set in motion were, according to Daniel Boorstin, among the most potent in modern history. Mathematics, science, philosophy, music–none of these would have taken the shape they did in the Western world without Pythagoras’ discoveries. And yet, of all the founders of the Western tradition, Pythagoras is, by far, the least known. This is unfortunate, for understanding Pythagoras and his thought is of much more than purely historical interest. Appreciating the influence of this first scientist and philosopher is essential if we are to get beyond a superficial understanding of history. This is particularly important when we consider the perceived gap between Hinduism and the thought of the West.

Personal Life

As with many figures from antiquity, facts about Pythagoras’ life are sketchy. Like his contemporary, the Buddha, he is said to be one of those divine men of whom history knows least because their lives were at once transfigured into legend. Nevertheless, a number of early writers have left us biographical information about Pythagoras which we have used to reconstruct his story in our book Divine Harmony: The Life and Teachings of Pythagoras.

Pythagoras was born on the Greek island of Samos around 569 bce. Miraculous events surrounded his life from the very beginning. Legend holds that he was the son of Apollo, the Hellenic god of music and learning, and his birth was foretold by the oracle at Delphi. His early years were spent studying at all the centers of scientific and sacred learning in Greece and the eastern Mediterranean. Eventually he made his way to Egypt, where he lived for over twenty years, absorbing Egyptian knowledge of mathematics, music, medicine and the mystical teachings regarding the soul and the stages of its evolution.

Pythagoras’ time in Egypt ended when the country was overrun by the armies of the Persian empire and he was taken into captivity in Babylon. This proved to be a blessing in disguise. Recognizing his prodigious learning and receptivity to new ideas, the Persian magi took Pythagoras into their confidence and he became a student of their equally ancient mystery school. He was also subject to other influences during this time, and probably undertook further travels. Whether he actually went as far as India is not known. Some writers think that he did. Others accept that he studied and absorbed in some form the Vedic philosophy of ancient India; certainly it was known in Persia at this time. And there was probably direct contact between India and Greece before the time of Alexander. Vitsaxis G. Vassilis, in his book Plato and the Upanishads, argues that exponents of literature, science, philosophy and religion traveled regularly between the two countries. He points to accounts by Eusebius and Aristoxenes, of the visits of Indian sages to Athens and their meetings with Greek philosophers. And reference to the visit of Indians to Athens is found in the fragment of Aristotle preserved in the writings of Diogenes Laertius who was also one of Pythagoras’ biographers.

The Teachings

The teachings that had the most influence on Pythagoras can best be discerned by what he himself taught. And his teaching began in earnest, when, at the age of 56, he returned from his travels and settled in the Greek world. Initially he returned to Samos and established a school there, but he found himself in great demand in the political arena, although he was more inclined to pursue scientific research, philosophical discussion and solitary contemplation. For this, he found the atmosphere more conducive in the city of Kroton, a Greek settlement in southern Italy. Here he established a philosophical community which was to become known as the Pythagorean brotherhood.

The essence of the doctrine that formed the basis for the Pythagorean community was conveyed, we are told, in the first lecture that Pythagoras gave to those who gathered there, attracted by the fame that now preceded him. He taught them that the soul is immortal and that after death it migrates into other animated bodies. He said that all living things are kin and should be considered as belonging to one great family. He introduced new explanations of gods and spirits, of the heavenly spheres, of all the natures contained in heaven and earth, and of all the natures in between the visible and invisible.

The Kosmos

From this comprehensive vision emerge all the details of Pythagorean philosophy. From the vision itself comes a central idea–Kosmos. The word was coined by Pythagoras, and its original meaning was more than merely everything that exists. The Greek root of the word also gives us the word cosmetic. It implies beauty, adornment, an aesthetic component that springs from an inherent order that Pythagoras described by the term Harmonia, the divine principle that brings order to chaos and discord. This order also expresses itself as philia, love or friendship. For Pythagoras, philia was a cosmic force that attracts all the elements of nature into harmonious relationships. It helps preserve the order of planets as they move across the sky, and encourages men and women, once their souls have been purified, to help one another. The greatest love, philia, for the Pythagoreans was wisdom, sophia. Thus Pythagoras was the first Western philosopher (philia + sophia).

Just as was thought in India, Pythagoras taught that, different songs and modes were appropriate to different hours and seasons. In the spring, for example, he would arrange a ritual in which a group of disciples would sit in a circle with a lyre player seated in the middle. As the instrumentalist produced a melody, the others would begin to sing together in a spontaneous fashion, from which would emerge a song in unison, creating a powerful sense of joy. This ritual was also modified for use as a medicine to treat diseases of the body. Many stories have been handed down that illustrate Pythagoras’ influence through music.

The Community

For the members of his brotherhood, the first goal of wisdom was attaining to the divine. And for this, Pythagoras recommended a highly disciplined lifestyle in a loving community. But entry into this community, essentially an ashram, required a lengthy and rigorous examination, including five years of silence. Once admitted to the inner circle, the students were exposed to abstract realms of study designed to turn attention to inner, universal values of consciousness for soul purification.

Modern science traces its origins to Pythagoras, but in its development dropped off the mystical teachings. Perhaps science needs to re-embrace the inclusive vision of this Western rishi.

For extracts from “The Life and Teachings of Pythagoras,” log on to www.harmoniainstitute.com/pythagoras.htm