Most of us college-educated Indians were taught that inefficient technologies and low productivities pervaded through long ages in practically all parts of India,” states Dr. S.K. Bajaj, director of the Centre for Policy Studies, a Chennai think tank. In the 1920s Gandhi’s Young India presented some proof of a rich and prosperous pre-British India. Then in the 1960s, the Centre’s founder, historian Sri Dharampal, discovered at the Thanjavur Tamil University a set of palmleaf records documenting a British survey of 2,000 villages of Chengalpattu, a large area surrounding present-day Chennai. “Startling features of Tamil society in the 18th century emerge from these palmleaf accounts,” said Bajaj. “Between 1762 and 1766 there were villages which produced up to 12 tons of paddy a hectare. This level of productivity can be obtained only in the best of the Green Revolution areas of the country, with the most advanced, expensive and often environmentally ruinous technologies. The annual availability of all food averaged five tons per household; the national average in India today is three-quarters ton. Whatever the ways of pre-British Indian society, they were definitely neither ineffective nor inefficient.”

Food production is just one aspect of the colonial impact being addressed by the Centre. The Chengalpattu records are part of Dharampal’s research which has uncovered a politically, technologically and economically vibrant Indian society of the 18th century. “That society was dismantled and atomized by the British, by force,” states the Centre’s brochure, “and the diverse skills of the Indian people were pushed out of the public sphere and made to rust and decay. For India to become a vibrant and dynamic nation again, we only need to re-awaken the political, economic and technological skills of our people.” The records are especially useful for understanding how Hindu religious institutions were originally supported, and why they declined under British rule.

Dharampal believes Indians must rediscover their nation’s traditional sense of chitta, mind, and flow of time, kala. “Since we have lost practically all contact with our tradition, and all comprehension of our chitta and kala, there are no standards and norms on the basis of which to answer questions that arise in ordinary social living. Ordinary Indians perhaps still retain an innate understanding of right action and right thought, but our elite society seems to have lost all touch with any stable norms of behavior and thinking. The present attempt at imitating the world and following every passing fad can hardly lead us anywhere. We shall have no options until we evolve a conceptual framework of our own, based on chitta and kala, to discriminate between right and wrong, what is useful for us and what is futile.”

The Centre’s three main researchers are: M.D. Srinivas, a theoretical physicist teaching at the University of Madras, who specializes in Indian science; T.M. Mukundan, a mechanical engineer specializing in technologies such as water management and iron smelting; and J.K. Bajaj, also a theoretical physicist, now involved in economy, agriculture and energy.

The Chengalpattu data was a Godsend for the Centre, and has allowed them to support many of their central theories about pre-British India. The accounts detail a complete economic, social, administrative and religious picture of the society. Every temple, pond, garden and grove in a locality is listed, the occupation, family size, home and lot size of 62,500 households meticulously recorded. Crop yields between 1762-66 are tallied. Per capita production of food in this region (which is of average fertility) was more than five times that achieved on average today.

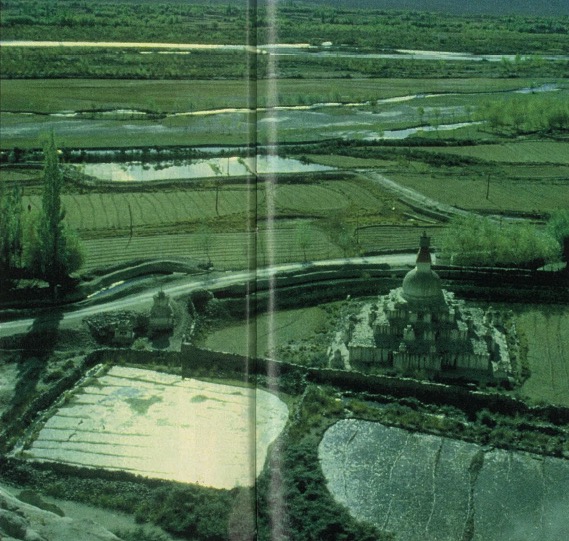

Bajaj and his associates didn’t do all their work in a library. The team set off in person across the Chengalpattu region to verify the picture presented in the leafs. They found most of these villages deserted–perhaps since the beginning of the 19th century–by all who had any resources, education or skills. Inhabitants had left behind their palatial houses, their temples and groves. Abandoned as well were the eyrs–the irrigation tanks and channels–often cut across by British-built roads which left dry land on one side and stagnant water on the other. Their on-the-ground inspection confirmed many aspects of the inscribed leaves.

Of importance to Hindu history is how the religious institutions were maintained. Lands called manyam were assigned for the support of various functions, including religious activities. Certain percentages of the production from this land were divided among the various public functions, such as administration, army, education and religious institutions. Small temples received income from nearby villages. Larger ones, such as those of the great center of Kanchipuram, received income from over a thousand villages. The amount dedicated to religion from the manyam lands, according to the leaves, was a substantial four percent of the total produce of the region. It supported temples, academies of learning, dancers and musicians. A portion was also provided for Muslim and Jain institutions. This system resulted in the vast network of temples, most now neglected, seen across South India.

The British government changed this system. In some areas they calculated a percentage figure of total tax revenue going to the institutions and fixed it as a dollar amount, in 1799 dollars. Some institutions still receive this same government allotment–worth next to nothing today. Others became owners of the land from which a share of production once came. This introduced its own set of problems, also still with us today, where temples are unable to collect the rent. The collective result was that the great religious and cultural institutions of the 18th century decayed and lost touch with the community. The British taxes were so high there was no money left to support the administration or cultural establishments. School teachers, musicians, dancers, keepers of the irrigation works, moved away, or took to farming. By 1871, 80% of the area was engaged in agriculture (up from less than 50% earlier), and many of the services and industrial activities that dominated the Chengalpattu society of the 1770s ceased to exist.

The value of the Centre’s research is obvious: India, and Hinduism with it, flourished in the not-so-distant past–without the Green Revolution or the Industrial Revolution or the Worker’s Revolution. Dharampal, Bajaj and their associates want India to look back at this time, dissect and understand it, and use that indigenous knowledge to reinvigorate the world’s largest democracy.

HOW THE GREEN REVOLUTION FAILED

Dr. Ramon De La Peña of the University of Hawaii is one of the world’s foremost experts on rice. He also happens to be a neighbor of the ashram from which Hinduism Today is produced. Asked to comment on the Chengalpattu reports, he said: “Such yields as 12 tons per hectare were definitely possible with the old methods and two crops a year. The best modern US production is eight to nine tons per hectare (one annual crop). The world average is presently three to five tons/hectare. Before the Green Revolution [which introduced new, high-yielding strains] the average was one to one-and-a-half tons/hectare. The Green Revolution worked in some areas but not in others. The short variety of rice developed for it grew just one meter high. To be productive, it needed fertilizer, and the fields had to be kept weed free. The old varieties were two meters high, not so suspectible to weed competition, resistant to insects and did not need fertilizer. If the new varieties are not managed correctly–with fertilizers, pesticides and insecticides–the harvest is less than with the old methods of minimum input. New is not always better.”

DHARMA’S FOUNDATION

Dr. J.K. Bajaj lauds duty to create and share abundance

All reliable statistics indicate that the average availability and consumption of food in our country is among the lowest in the world. We on the average eat at least one-third less of staple foods than the norm in almost every other part of the world. And India is perhaps the only major country of the world where cattle do not share in the produce of the lands. The Indian people and cattle are living in a state of hunger while highly fertile Indian lands, even those that fall in the plains of the great life-giving rivers, such as the Ganga, are lying idle. This has been the situation of India for about two hundred years.

India was never so callous about scarcity and hunger. Growing an abundance of food and sharing it in plenty, annabahulya and annadana, have always constituted the foundation of dharma. All else, even the search for moksha, liberation, is built on this foundation. We believe that if India is to come into her own and assert her civilizational greatness in the present-day world, then first of all we have to overcome scarcity and recover the traditional discipline of ensuring plentiful food to share with all.

In order to propagate and make this discipline a national priority, we invited prominent saints to the temple of Sri Tirumala, Andhra Pradesh, on October 11, 1996. Srimat Kaliyan Vanamamali Ramanuja Jeer Swami told our gathering that scarcity in India is not merely an economic failure, it is a moral failure. Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Shankaracharya said we neither need to learn anything fresh from anywhere, nor establish any new institution. We only have to recollect the memory of the discipline that has always been with us. Tirumala-Tirupati Devasthanam’s executive officer, M.K.R. Vinayak, said annadana was discontinued not due to a lack of foodgrains, but a lack of moral values. The assembled saints unanimously blessed the release of our book, Annan Bahu Kurvita, in Hindi, Tamil and English, which treats all aspects of annabahulya and annadana.

Annan Bahu Kurvita is available from: Centre for Policy Studies, 2, Thyagarajapuram, Mylapore, Chennai, 600 004, India.