The new Hindu Community Institute has begun training religious counselors to meet the needs of Hindus in America

By Gaurav Rastogi, California

A few years ago, an unshakable thought began to settle in my mind—“Engage more in the world, for dharma.” What could it mean? Was it a call to action? It has taken me some time to figure it out. What more could I do beyond the teaching and writing I already did around yoga and dhyana? I kept looking for ideas. One day I heard a talk about a new institute that was looking for volunteers. I showed up at the first board meeting of a small group that became the Hindu Community Institute (www.hinduci.org). This is our story from that modest beginning.

Have We Done Our Duty?

Our group had first come together during the 2016-2018 debate over the portrayal of Hinduism in California middle-school textbooks. In subsequent years, we met every week to deliberate: “We have made our money, achieved our success, but have we done our duty?” The answer was clear. We all perceived a sense of loss and disconnection from our religious and cultural inheritance. Hindus have a rich and long tradition, but we ourselves had done little to bring it with us to the United States, where we had come in search of a better life. While we developed our careers, Hindu ideas continued to travel out into the West and achieve mainstream acceptance. Yoga, pranayama, reincarnation, karma, meditation, vegetarianism, cremating the dead—even putting haldi (turmeric) into your milk—these are no longer considered fringe ideas here. But what had we done to present the system of living that these ideas had come from? While good ideas have been absorbed piecemeal from Hindu tradition, the image of Hinduism in the popular mind remains limited to the cliche of caste, cow and abject poverty. Our rich philosophy and tradition are unrecognized in the West, though certain elements are pervasive everywhere, unbranded.

Our more recent immigrant families, also, have continued the tradition of education and career enhancement, making us the most successful minority group in America. But while our kids win spelling bees and robotics competitions, we have not given them the rich stories of our tradition that have been in our DNA for hundreds of generations. We have also failed to communicate to our children that our tradition extends beyond the visits to temples and observation of festivals. The river Sarasvati, when it began to dry up in ancient times, still flowed strongly from the Himalayas for centuries, but disappeared hundreds of miles before reaching the ocean. Like that, our tradition, we felt, is going to dry up unless we do something. We carry a debt to our ancestors who have transmitted the tradition over the millennia. We owe it to them to pass it on to the future through our children and, in the process, hopefully even enhance it.

Tradition, like muscle, is a use-it-or-lose-it proposition. A few generations of under-use or outright neglect makes a tradition archaic and meaningless. It is only by putting the Hindu tradition’s knowledge to use to improve our lives today that we can insure its transmission into the future. There are, however, structural differences between the Western society we now live in and the traditional dharmic society of India. It is not obvious how to perpetuate our tradition outside the context of India. We need to be careful and methodical with our approach here. We need to understand the problems in modern society and take an unromantic look at how the Hindu tradition can help.

The Modern Diaspora Business

Hindu culture and religion have been transmitted outside India before—to Southeast Asia hundreds of years ago and to multiple countries, such as Mauritius, Fiji, South Africa and Trinidad, in the 19th century, usually through indentured servitude. Those Indian communities mostly remain Hindus; so it can be done. But modern times present different challenges, so we reached out for ideas and inspiration to other traditions, including the Jews, Buddhists and Muslims, who have dealt with America’s particular issues. They were most helpful.

Central to my own position on this is that since the Hindu tradition is a lived and living tradition, we should not treat it as a museum artifact that should be “preserved.” Our approach to teaching should not be looking back at India with a sense of nostalgia, but looking forward, into the future. How can we make the tradition more meaningful to the generations to come, living here in America, many of whom will have no memories and little connection to India?

First, we must address the structural differences. Without acknowledging these differences, we will fail to find the methods that stick. Culture and dharma are both very subtle. The Western society is based on the Abrahamic traditions, which tend to congregate on the weekend (Friday, Saturday or Sunday). This allows members to have a better sense of community, including pooling tithes or mandatory income shares, and the preacher can serve as the one-stop shop for connection to God, as a healer for his “flock,” as a source of insight into scripture and as a receiver of confidential information about matters of the spirit. These are religions organized on a congregational model.

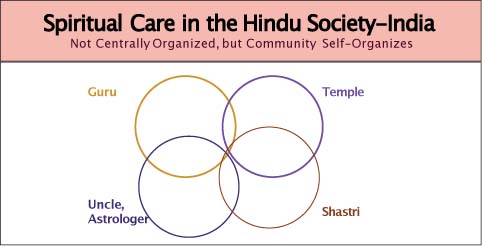

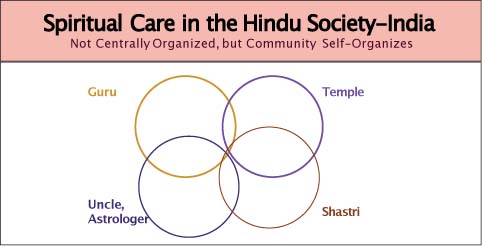

The Hindu tradition, like most dharmic traditions, is different. We do not require people to come to the temple on a single day—I jokingly say, “We do not congregate, rather, we crowd.” We do not have a requirement to donate a tenth of our income. We do not excommunicate people for not following the rules. In India, we do not rely on the temple priest for sermons on the scripture or confidential advice on family issues. Our temples do not offer the spiritual care services that churches and mosques do. In so many ways, Hindu society is connected differently from the Western model. No doubt Hinduism meets the spiritual, social and emotional needs of society, perhaps better than any Abrahamic religion. But it does so in a different pattern, one not centered around a single institution, such as a church, mosque or temple, but one involving teaching lineages, ashrams, extended family and more. We cannot hope to transmit tradition in the West without fully considering these structural differences.

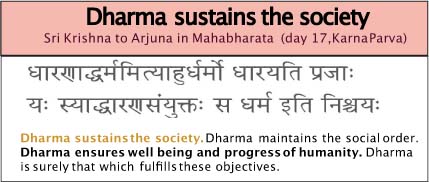

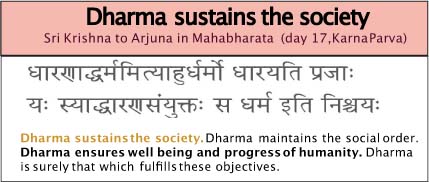

Dharma is the connective glue of society. It preserves and sustains society. This realization led our group to a crucial insight—modern society ails to the extent that it is not dharmic. Let me explain. Loneliness is the disease of our times. We are lonely, all of us, and this loneliness comes from the loss of connection to each other, to meaning and to our own inner selves. Can we restore that sense of connection and community? Can we recreate the Hindu society’s system of spiritual care in the West?

Using the Silicon Valley Mindset

What do you think of when you hear of Silicon Valley? Perhaps technology, innovation and unparalleled wealth. All these are true, but we think of Silicon Valley as an approach, a mindset—seeing “opportunities” instead of “problems;” having a sharp intuition about customer needs and effective solutions; being methodical, not lumbering; “staying hungry;” being able to work with minimal funds; being agile, alert and responsive to market feedback; having energy that comes from momentum; high emphasis on process and repeatability for scale; open-source in creating and sharing; using technology for leverage and building for scale; dreaming big and moving fast. These are some of the ideas that have made Silicon Valley the dominant industrial force of our generations. The Hindu Community Institute’s core team decided to apply the same intellectual drive and honesty from our professional careers to our work for dharma.

Society as Air-Conditioning for the Emotional Self

I like to think of a well-functioning society as a kind of air-conditioning for the emotional self; to keep all of us in a comfortable range by sharing both our excess sorrow and happiness. My personal theory is that loneliness is disease-causing because these excesses of happiness and sorrow create a state of dis-ease, where we are unable to feel a sense of enjoyment. If we can restore our connections to society and dharma, we can restore that sense of ease with our own selves.

Our group ran a series of conversations to understand the life events where the emotional states can spike, and where spiritual care can provide air-conditioning. This led to our “Meeting the Needs” chart (beginning of article), which we used to think about how tradition and connection can help in improving each of these life states. This, in turn, led to the creation of spiritual care services, such as pre-marriage counseling, memorial speaking, compassionate presence, and so on, that did not exist in the Hindu community as distinct services so far.

Counselor of Hindu Tradition

We created a graduate certificate course—“Counselor of Hindu Tradition,” abbreviated CHT—to fulfill the needs of the community. These trained CHTs effectively serve as members of one’s extended family in times of need. The CHT course runs for nine months—24 Sundays, online. We teach aspects of the Hindu tradition, the action philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita, compassionate presence, counseling, and dealing with medical and ethical situations around the passage of life. By “compassionate presence” is meant the simple act of being there for a person in distress, without judgment or necessarily answers for them, but with deep sympathy and, when appropriate, spiritual insight or direction.

We can share a few real-life experiences our Counselors of Hindu Tradition have reported.

In the first, a woman wanted someone to speak with her ailing mother who was suffering from a terminal disease and dealing with pain. Her CHT met the mother for two sessions to offer compassionate presence, and to teach her basic pranayama techniques for pain management. In the second example, a couple lost their oldest son, 12, in a freak accident at the beach. Our CHT met the family for several sessions to offer compassionate presence, a Hindu perspective on death, and to suggest traditional approaches for closure in such circumstances. Very recently, a man who lost his wife to the pandemic called our CHT to speak at her memorial. They offered a brief uplifting talk about grief, death in the Hindu tradition and reflections on the true purposes of life. Our last example involved a domestic violence issue. We spoke with the victim to understand the problem, and then connected her with a partner organization that deals confidentially with such issues.

The course is taught by forty faculty, including leading practitioners of their craft. For example, we learn what happens in the emergency room from Stanford’s head of emergency services. We learn Hindu last rites from a trained priest. We learn aging and geriatric care issues from leading doctors, and so on. We have built the program from the ground up, with advice from experts in education, chaplaincy and spiritual care as well as “service learning”—a combination of classroom learning with hands-on volunteer experience.

We have run three cohorts and are starting the fourth as this article is published. Our 65 graduates are all around the US and a few in India as well. These are people interested in learning how to serve, and in HCI they have found their sangha or community. Our CHTs can serve as volunteers in the community lifelong, or they can go on pursue the formal professional path of chaplaincy through the accredited Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley. Between volunteering and professional work, we have therefore created a “continuum of spiritual care” in the community. An extended ongoing relationship with the community allows us to create an organized framework for the ongoing giving of spiritual care, instead of simply graduating individuals without a clear path of service before them.

Challenges in Building a Hindu Voluntary Organization

The pandemic forced us to reevaluate the financial and physical structure of the organization. We switched to a completely online learning model, which actually works better for students across the US. Additionally, it allow us to bring in faculty from anywhere on the planet. As the pandemic recedes, we expect to keep our classes online and meet socially in person wherever possible.

Building community trust is critical, and we have tried to gain this by better governance, leadership and communications. In the age of weaponized language, we chose to call ourselves a “Hindu” organization with pride, but we have decided to be apolitical and independent in our actions. We maintain formal procedures and carefully document our board meetings.

Another problem we face is that while Hindus in America are well off, we have not yet developed a tradition of abundantly funding community projects other than temples. We presently receive a large number of small donations by check. This will change over time, but we are being as frugal as we can while moving forward. We are currently raising money to hire our first administrative staff and for partial scholarships for those pursuing the chaplaincy program at GTU.

One of our most effective innovations has been the linking of karma yoga, selfless service, to spiritual care. Each of us has a tremendous innate capacity to serve. How can this capacity be expressed? We created “Om dollars” to tap into our innate desire to serve. These work like regular dollars in the sense that you can earn them, count them, admire the balance and pass it on to your future generations. You just can’t spend it or convert it into treasury dollars. We use a desire we already have—earning money in dollars—and turn it into a dharmic idea by converting the question “How can I earn more money” into “How can I serve the society better in order to earn more Om dollars?” This started as a lighthearted reference, but we soon realized the power of the idea when our students asked how they could earn more! Most students now pay us in Om dollars, and our leverage is that we generate nine Om dollars for every dollar of donation. Our teachers serve pro bono and gladly return to teach every year. We started free yoga classes during the pandemic, and we now have 50 teachers that have delivered nearly 3,000 free classes online so far.

Karma Yoga for Loka Samgraha–the Welfare of the World

And so, this is how I have come to realize the full meaning of the unshakable thought that drew me in this direction; it is the desire to spread well-being in society through selfless service. For the remainder of my life, this is my mission. Building what we hope will one day be a global Hindu institution from Silicon Valley has been a great learning experience, and one I hope everyone will participate in. Our currency is authenticity—we are karma yogis ourselves, and people that are attracted to our work are drawn to us by their own desire for loka samgraha. We have just begun. Society needs many scores of such institutions to fully bring the richness of the Hindu tradition into the modern world, and to improve the world for everyone, not just Hindus. Let us join hands.

Gaurav Rastogi, an entrepreneur with twenty years of executive experience, holds an MBA from IIM Ahmedabad and a Mechanical Engineering degree from Delhi Technological University. He is a yoga and dhyana meditation teacher, and a board member of the Hindu Community Institute. He is married with two grown kids and lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. gauravhinduism@hinduci.org